Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief and The Wrecking Crew

Strange tales from the church of Xenu, and the secret weapon of '60s rock.

By now, open mockery of the Church of Scientology is an international pastime. YouTube abounds with videos of the cult's celebrity devotees and zomboid inquisitors. And the group's nutty particulars —the mad founder; the "billion year" membership contracts; the evil Xenu, galactic bad boy of 75,000,000 years ago—are a source of continuing amusement. But Scientology remains a faintly sinister organization. Fattened with cash by a dubious IRS decision that awarded it tax-free status in 1993, it is a church whose chief sacrament is litigation, and it has been as savage in its attacks on critics as it is relentless in its harassment of apostates.

None of this will be news to longtime Scientology observers. But Alex Gibney's new documentary, Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief, helpfully assembles a lot of it in one place, and the film will likely pop some eyes among those only casually acquainted with the church's bizarre workings.

The picture is based on a 2013 book by Lawrence Wright, which grew out of a New Yorker profile of the writer and director Paul Haggis (Crash), a bitterly disaffected former Scientologist who bailed out of the faith in 2009, after 34 years as a true believer. Haggis—who broke with the church over its hostility toward homosexuality (he has two gay daughters)—is joined here by Wright himself, and by a number of other dropouts, among them former Scientology executives, rank-and-file members (including Jason Beghe, star of the TV series Chicago P.D.), and a very talkative PR woman named Sylvia "Spanky" Taylor, once employed at Scientology's Hollywood Celebrity Center as a handler for John Travolta.

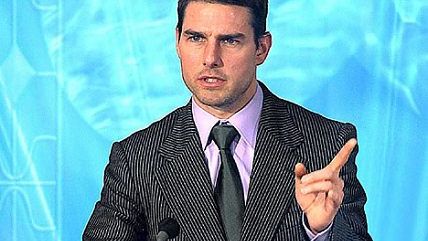

The Oscar-winning Gibney (Taxi to the Dark Side) smoothly blends his talking heads with little-seen footage of wacky Scientology gatherings (one of them a 42nd-birthday party for Tom Cruise at which the star breaks into a hip-shaking reprise of his "Old Time Rock and Roll" number from Risky Business). There are also vintage interviews with the late L. Ron Hubbard, the charismatic fabulist who created Scientology (mainly as a tax dodge, it seems). Hubbard's background as a pulp science-fiction writer was instrumental in the invention of this new theology, so heavily concerned with outer space and past lives (Hubbard is said to have believed he was once a Phoenician prince). As Wright says, "Scientology really is a journey into the mind of L. Ron Hubbard."

In touring the usual checkpoints of Scientology takedowns, we naturally see the E-meters—primitive lie detectors—that gauge initiates' responses to questions like "What are you most afraid of?" and "Do you have a secret you're afraid I'll find out?" The purposes to which such intimate information could be put is an issue that hovers over the film's sections on Cruise and Travolta. (Similar dirt-digging has long been suspected in the IRS' sudden reversal of its decades-long denial of tax-exemption for the church—a turnabout that has enabled Scientology to hire fleets of top lawyers to pursue its innumerable lawsuits, and to build a worldwide real-estate portfolio worth a reported $3-billion.)

Letters from Hubbard's second wife, Sara Hollister, are quoted in voiceover ("I felt he was…hoodwinking people"), and there are disturbing tales from the Sea Org, Scientology's quasi-naval auxiliary, and the Rehabilitation Project Force, a sort of prison camp for wayward members. We also see current Scientology leader David Miscavige, with his clenched grin and lasery eyes, presiding over a rally at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena on a neo-Nuremberg stage set that might have been designed by Albert Speer. (It's too bad the film had no room to include the church's decade-long legal onslaught against TIME magazine, which in a 1991 cover story titled "The Thriving Cult of Greed and Power" called the church "a hugely profitable global racket." (Scientology's charges were eventually dismissed.)

The church denies virtually everything that's written about it. But while it has claimed to have 8,000,000 members, the real number, according to Wright, is closer to 50,000. As they move up the "Bridge" of Scientological enlightenment, these aspirants are charged ever-increasing amounts of money for their next infusion of knowledge. And what do they get for this near-endless outlay? Haggis found out, because he finally achieved the ultimate enlightenment in a document, written in L. Ron Hubbard's own hand, which laid out the whole belief system. Haggis, who says he had previously never read anything critical of Scientology, was staggered by what he read there—the interstellar overlord, the enslaved aliens, the body thetans and whatnot. He recalls shaking his head in wonder and saying, "What the fuck are you talking about?" And then he was gone.

(Going Clear opens in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco this weekend. It debuts on HBO on March 29.)

The Wrecking Crew

The Wrecking Crew is a rare labor of loving commitment. It's an evocative documentary about a group of Los Angeles session musicians who in the 1960s and '70s played on a dizzying array of records by acts ranging from the Beach Boys and the Mamas & the Papas to Frank Sinatra and Nat "King" Cole. Also the Mothers of Invention, the Byrds, and Simon & Garfunkel. Also Barbra Streisand. They were a shifting group of maybe 20 musicians, but they were so in-demand, and played so many sessions together, that the key players became a great band. "They were so tight," says Micky Dolenz, whose own group, the Monkees, benefitted greatly from Wrecking Crew backup.

Director Denny Tedesco began shooting this film in 1996, the year his father, Wrecking Crew guitarist Tommy Tedesco, was diagnosed with cancer. He quickly reunited his dad with a number of old colleagues, among them bassist Carol Kaye (who had played guitar on Ritchie Valens' 1958 hit "La Bamba") and the mighty drummer Hal Blaine (whose indelible stomp opens the Ronettes' "Be My Baby"). Tedesco filmed them all sitting around a table telling stories about the old days, and then, after his father's death the following year, spent the next decade scrounging for money to finish his picture, which required licensing for more than 120 music cues. We can be thankful that he found it.

The Wrecking Crew evolved out of Phil Spector's "Wall of Sound" sessions at Gold Star Studios in the early '60s. Many of the musicians were New York players, drawn west by the easy living and abundant studio work. ("I was makin' millions of dollars," says Blaine.) It was a magical time, nicely summed up by songwriter Jimmy Webb: "The perfumed air, the night-blooming jasmine, the sound of the Beach Boys wafting from house to house…how dreamy it all was."

Beach Boys leader Brian Wilson, who worshipped Spector's records, started booking Phil's musicians to play his own sessions. "They were the ones with all the spirit and all the know-how," he says, "especially for rock & roll." You can hear the Crew players starting to weigh in on singles like "Fun, Fun, Fun" and "I Get Around," then growing more numerous on tracks like "California Girls," and finally—when Wilson decided to remain in the studio while the Beach Boys went out on the road—taking over almost completely for "Good Vibrations" (a three-month recording project) and the epochal Pet Sounds album. (The Beach Boys' incomparable vocals of course remained an indispensable element of all their records.)

Tedesco makes astute use of old photos and, to a lesser extent, studio footage to accompany reminiscences by such Crew members as guitarist Al Casey and keyboardists Leon Russell and Don Randi, and reflections by such scene veterans as Herb Alpert, Frank Zappa, Dick Clark, and onetime backup singer Cher. Among the many tangy recollections of how things worked back in those studio days is one provided by Byrds leader Roger McGuinn, who describes showing up in the studio to record "Mr. Tambourine Man" and finding himself the only Byrd on hand—some Wrecking Crew guys handled everything else. McGuinn says they were able to lay down two tracks that day, in one three-hour session. Later on, he adds, when all of the Byrds went into a studio to record "Turn! Turn! Turn!" it required 77 takes.

The Wrecking Crew was a secret weapon that remained secret for years. Dick Clark says, "I had no idea certain people didn't play on their own records until the Monkees came along." As for the record companies that commissioned these hits, "All they wanted was the product. Who created it? That was incidental."

Not anymore.

Show Comments (70)