Our Crazy Laws on the Insanity Defense

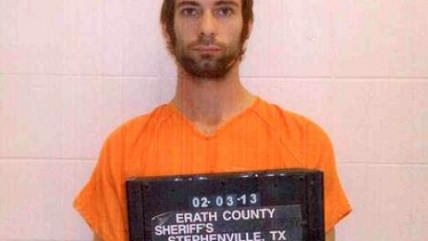

The failure of Eddie Ray Routh's insanity defense calls into question the meaning of the term.

When a Texas jury rejected an insanity defense and convicted Eddie Ray Routh in the murder of "American Sniper" Chris Kyle and Chad Littlefield, it raised a question: If this guy isn't crazy, who is?

Routh had a voluminous history of mental illness. After being discharged from the Marines in 2010, doctors hospitalized him because he thought a giant tapeworm was eating him. He had several more stints in psychiatric facilities and regularly took medications for psychosis.

A few weeks before the shootings, doctors concluded he was a danger to himself and others. After his final release from a Veterans Administration hospital in January 2013—over the objections of his mother—Routh got worse. He said his co-workers were planning to eat him and "the heater in the workroom was a large human rotisserie," as The Dallas Morning News reported.

Traveling to a gun range with Kyle and Littlefield, he behaved so strangely that Kyle texted Littlefield, who was sitting next to him: "This dude is straight-up nuts." Routh, who was in the back seat, said he grew angry during the drive because they tried to get him to eat something and "nobody would talk to me."

"It smelled like sweet cologne," a jail guard heard him say. "I was smelling love and hate." He also said, "I'm sure they've forgiven me." When he arrived at his sister's house in Kyle's truck after the murders, she testified, he "was talking about pigs sucking his soul."

But the jurors needed less than three hours to decide that for purposes of criminal law, Routh was as sane as Tom Hanks. Maybe they were persuaded by the steely logic of the prosecutor who said the defendant's subsequent visit to a Taco Bell confirmed his mental fitness.

"What does it take to go and order fast food?" asked Assistant District Attorney Jane Starnes. "So you've got to go through the right lane; you've got to place your order; you've got to interact with the clerk; you've got to give them the money, get your change, get your food and go. It's not something that somebody who's just out-of-their-mind delusional does."

Really? My suspicion is that even delusional people need food and recognize Taco Bell as a place they can get it. I would bet plenty of fast-food employees have encountered customers who are a few fries short of a Happy Meal.

Nor did prosecutors offer any compelling theories why Routh would commit what they called the "cold, calculated capital murder" of two new acquaintances who were going out of their way to help him. The only reasons he had to kill Kyle and Littlefield were loony ones.

But it didn't matter. Under Texas law, his attorneys had to prove that their client, "as a result of severe mental disease or defect, did not know that his conduct was wrong." That hurdle is almost insurmountable.

Mental Health America of Texas, an education and advocacy group, has said the requirement does not "allow a jury to consider the true effect of mental illness on an individual who suffers from psychosis, delusions or irrational beliefs" and is "unable to appreciate the moral wrongness of their action or conform their behavior to the law." Texas Tech law professor Brian Shannon has written that the Texas standard "is so narrow that it is virtually meaningless."

That's not a bug; it's a feature. The insanity defense has never sat well with many Americans, who have no use for the notion that anything can excuse serious criminal violence.

The idea that some people are not responsible for their crimes because their minds are defective offends our normal moral standards. It's easier to dismiss it than to acknowledge the complexity of the world. Some states have abolished the insanity defense altogether, and others hardly need to.

No one wants psychotic killers set free to follow their dangerous impulses. Under a more sensible set of laws, though, someone like Routh would not be sent to a Texas prison to rot for the rest of his life. He'd be confined to a mental institution where he could be thoroughly treated—and kept off the streets unless and until he is no longer a hazard to anyone.

Instead, we act as though such defendants are as capable as the rest of us of behaving rationally and responsibly. In this case, that is straight-up nuts.

Show Comments (98)