How the War of 1812 Eroded U.S. Liberalism

The War of 1812 helped "the State come into its own" by concentrating power and interest in the national government.

In 1918, having watched in horror as his Progressive friends gleefully jumped onto Woodrow Wilson's war wagon, Randolph Bourne penned the immortal words: "War is the health of the state." As he explained it,

The republican State has almost no trappings to appeal to the common man's emotions. What it has are of military origin, and in an unmilitary era such as we have passed through since the Civil War, even military trappings have been scarcely seen. In such an era the sense of the State almost fades out of the consciousness of men.

With the shock of war, however, the State comes into its own again,…

[I]n general, the nation in wartime attains a uniformity of feeling, a hierarchy of values culminating at the undisputed apex of the State ideal, which could not possibly be produced through any other agency than war. Loyalty—or mystic devotion to the State—becomes the major imagined human value.

An earlier group of Americans would have agreed, although they would not have shared Bourne's horror. These are the men who sought war with England in 1812. As Wikipedia notes,

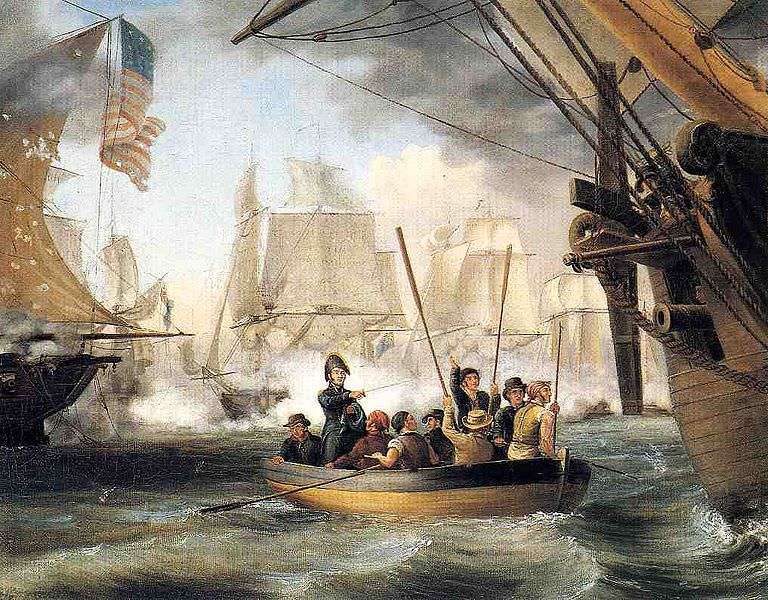

The United States declared war on June 18, 1812 [after close party votes in Congress] for several reasons, including trade restrictions brought about by the British war with France, the impressment of American merchant sailors into the Royal Navy, British support of Indian tribes against American expansion, outrage over insults to national honor after humiliations on the high seas, and possible American interest in annexing British territory in modern-day Canada.

I will explore neither the justifications for the war nor the terms of the Treaty of Ghent. Suffice it to say that Britain ceased its impressment policy before the war started and sought to reconcile with America after the war, opening up opportunities for westward U.S. expansion at the expense of Spain and the Indians. Instead I'll focus on how the war eroded liberalism in the United States by concentrating power and interest in the national government. There's a lesson here: even a war that appears justifiable—Britain conscripted Americans into its navy and interfered with commerce—had enduring illiberal domestic consequences beyond the immediate transgressions of taxes, debt, and trade embargoes—dangerous precedents were set.

While I don't wish to overstate the liberalism of prewar America—slavery and the war on Indians were only the most egregious violations of the principles of liberty—it would be wrong to think that America did not become less liberal with the war, that Bourne's maxim was suspended in this case. It was not suspended.

Prewar, there were still eminent voices favoring small government and decentralized power. Postwar, this was hardly the case. Indeed, the idea of a "living constitution" seems to have been born in this era. The War of 1812 should bring to mind the French saying "The more it changes, the more it's the same thing."

In the final chapter of The Radicalism of the American Revolution, historian Gordon S. Wood notes that as the 19th century unfolded, the survivors of the founding generation were unhappy with what they saw in America. "It was increasingly clear," Wood writes, "that no one was really in charge of this gigantic, enterprising, restless nation … the most thoroughly commercialized society in the world."

Why would the last of this generation despair? Because "the founding fathers, of course, had thought that eminent men and imaginative minds were in control of events and caused things to happen. But the heroic conception of society was now relegated to a more primitive stage of development." Thus,

This democratic society was not the society the revolutionary leaders had wanted or expected. No wonder, then, that those of them who lived on into the early decades of the nineteenth century expressed anxiety over what they had wrought….

Indeed, a pervasive pessimism, a fear that their revolutionary experiment in republicanism was not working out as they had expected, runs through the later writings of the founding fathers. All the major revolutionary leaders died less than happy with the results of the Revolution. The numbers of old revolutionaries who lost faith in what the Revolution had done is startling.

To their dismay, people were more concerned with their personal economic affairs than with the new nation. "White males had taken only too seriously the belief that they were free and equal with the right to pursue their happiness," Wood writes. Thus commercial success outweighed republican virtue, disappointing Hamiltonians and Jeffersonians alike. "A new generation of democratic Americans was no longer interested in the revolutionaries' dream of building a classical republic of elitist virtue out of the inherited materials of the Old World."

As a result, "the founding fathers were unsettled and fearful not because the American Revolution had failed but because it had succeeded, and succeeded only too well."

The retired founders were not the only ones who worried. They were joined by the men who still exercised power, especially Republicans James Madison and James Monroe, and such influential men of the next generation as John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun. As war with England approached, Republicans (as opposed to the Federalists) had no problem finding silver linings. War would not only inject government with a new dynamism—with important implications for trade policy, money and banking, and internal improvements—it would also give the people a shot of badly needed national spirit.

Thus the War of 1812 is an underrated turning point in American history, rivaling the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, and the two world wars. Indeed, the War of 1812 helped to launch the empire that manifested itself in those later conflicts. In its aftermath, America's rulers could believe that their continental and global ambitions, backed by the army and a global navy, were fully realizable. They just needed a government equal to the task.

It's not too much to say that modern America was born in 1812–1815. While it was a Republican war—Federalists in the northeast opposed and even threatened secession over it—the postwar Republican Party took on most of the fading Federalist Party's program with respect to the role of government in the American economy. Advocates of smaller, decentralized government (Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren, among others) rallied in the decades before the Civil War, but in the end the neomercantilists—advocates of Henry Clay's Hamiltonian American System—triumphed to the point that Grover Cleveland, outraged by the rampant privileges for business insiders, railed against what he called the "communism of combined wealth and capital" that had given rise to communism in its ordinary sense.

Before open hostilities with England broke out, Wood writes in another book, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815, "America had been engaged in a kind of warfare—commercial warfare—with both Britain and France since 1806." As president (1801-1809), Thomas Jefferson had pushed Congress to impose a general trade embargo—a ban on all American exports—during the Napoleonic wars, when American merchant ships (and a warship) were interfered with, American neutrality violated, and merchant seamen impressed into the Royal Navy. Jefferson called this response, which was highly divisive, "peaceful coercion" and an alternative to war. Wood adds, "The actual fighting of 1812 was only the inevitable consequence of the failure of 'peaceful coercion.'"

To be continued…

This article originally appeared at The Future of Freedom Foundation.

Show Comments (202)