Lunar Licensing: Promoting and Protecting Private Business on the Moon

Why not instead an interplanetary Homestead Act and Mining Law?

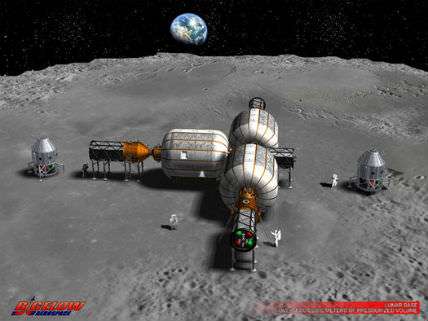

Last year, Bigelow Aerospace, a company that is developing inflatable outer space habitats, asked the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to consider using its licensing powers to protect private sector assets on the Moon. The company is aiming to set up such a base by 2025. Earlier this month, the agency issued a letter assuring the company that would it use its licensing powers in such a way as to prevent harmful interference from other private companies that the agency would also license.

So why can't Bigelow and other companies simply make a claim to a couple of square kilometers of the Moon and start hotel operations, mining, or any other activity that it believes will be profitable? Short answer: The Outer Space Treaty of 1967. Article II of that treaty reads:

Outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

In addition, Article VI states:

The activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty.

The idea embodied in the FAA letter is that the requirement for "authorization and continuing supervision" gives the FAA authority to license private activities of American companies. Once licensed, the State Department would be able to negotiate agreements with other countries to respect the the perquisites of FAA lunar licensees.

Why not just say to hell with it and throw the whole treaty away? After all, Article XVI allows:

Any State Party to the Treaty may give notice of its withdrawal from the Treaty one year after its entry into force by written notification to the Depositary Governments. Such withdrawal shall take effect one year from the date of receipt of this notification.

Well, maybe because the development of the the American frontier was guided and regularized by what amounted to licensing schemes. As space exploitation develops, the Outer Space Treaty will need to be amended to include provisions similar to the Homestead Act of 1862 that governed how property rights to federal lands were divvied up and the Mining Law of 1872 which allowed miners to make claims to explore for minerals and establish rights to federal lands without authorization from any government agency.

The legal situation with respect to exploiting the Moon could have been worse. Consider this provision from the 1979 Moon Treaty:

Neither the surface nor the subsurface of the moon, nor any part thereof or natural resources in place, shall become property of any State, international intergovernmental or non-governmental organization, national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural person. The placement of personnel, space vehicles, equipment, facilities, stations and installations on or below the surface of the moon, including structures connected with its surface or subsurface, shall not create a right of ownership over the surface or the subsurface of the moon or any areas thereof.

Fortunately, the United States has never signed that document.

For more background, see my colleague Katherine Mangu-Ward's excellent article on the current state of private space exploration, "Rocket Men." See also my article, "Does Mars Have Rights?"

Show Comments (113)