Professors Resist Higher Education Innovation

Some vendors of higher education may have to be dragged, kicking and screaming, to make improvements

To bone up on Spanish for an upcoming trip, I installed the Duolingo app on my phone and tablet. My son also studies Spanish online—then again, he studies everything at home through a mix of online instruction and printed materials. The lessons are good—the app lets me learn at my own pace, as does Anthony's "school," which also features a more challenging curriculum than we can find locally. The costs are reasonable: Duolingo is free, while my son's tuition is a fraction of what the average public school spends per-pupil. And never once have we encountered a trigger warning, been cautioned over inclusive language, or been asked to create a safe space at the kitchen counter where we work (which is good, because the knife I just used to make a sandwich is awfully sharp and pointy).

If innovation can make not just language studies, but fourth grade, more individualized and accessible, can't it find us a way out of the expensive marinade of crazy that colleges and universities seem to have become?

Yes it can. But some vendors of higher education may have to be dragged, kicking and screaming, to make improvements.

Two points jump out at me from the recently released 2014 Survey of Online Learning, which polls officials at 2,800 colleges and universities. One is that 70.8 percent of academic leaders say that online learning is critical to their institution's long term strategy, up from 48.8 percent in 2002.

The second point is that 28 percent of chief academic officers report that faculty members "accept the 'value and legitimacy of online education,' a rate substantially the same as it was in 2003."

So college and university administrators whose institutions exist to educate—share information with students—believe it's "critical" to use the greatest system for delivering information ever devised by man, but they're getting resistance from employees who'd rather cling to the old-fashioned way.

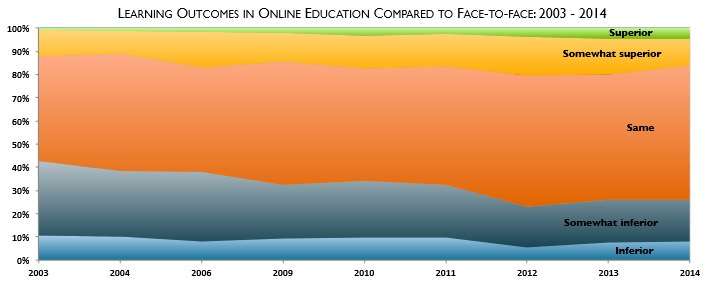

Despite the resistance, the number of students taking at least one online course increased by 3.7 percent last year, though that's the lowest growth rate recorded since the survey began in 2003. Is the hesitation because of doubts about the quality of online education? Not really. About three-quarters of respondents consider "learning outcomes" for online education to be the same or better then those for face-to-face education.

This squares with research which found, even before the age of conjugating "aprender" on your smart phone, that online education can be at least as good as the classroom kind.

Tellingly, those with actual experience in teaching using modern technology have a more positive opinion. The survey notes:

A consistent finding over the twelve years of these reports is the strong positive relationship of academic leaders at institutions with online offerings also holding a more favorable opinion of the learning outcomes for online education. The current results are no different–chief academic officers at institutions without distance education courses are more than twice as likely as those at institutions with such courses to report online learning outcomes are Inferior or Somewhat Inferior to those for comparable face-to-face courses.

The survey doesn't address how much colleges charge for their offerings, though it does discuss means by which online learning can reduce costs. But plenty of higher education students have discovered what my son and I know: that modern technology makes it possible, if done right, to deliver education much more cheaply than in a face-to-face setting.

That's an important point when the college bubble is very obviously a real concern. "Average published tuition and fees at public four-year colleges and universities increased by 19% beyond the rate of inflation over the five years from 2003-04 to 2008-09, and by another 27% between 2008-09 and 2013-14," the College Board noted, though prices have finally slowed their rise.

And for those hefty prices, we get not just the challenge of securing some kind of reasonable return on the investment, but an academic culture that is increasingly mockable. Far from environments of intellectual ferment and debate, too many traditional institutions of higher learning have become dens of groupthink where straying outside the lines in terms of thought and language can draw censure and penalty.

A majority of college professors refuse to "accept the 'value and legitimacy of online education"? Fine. Make them exhibits in the museums of intellectual fail their cozy homes are becoming.

And develop some more damned learning apps.

Note: The publishing firm Pearson is a sponsor of this survey and is accused of profiting from unethical tactics in its education deals. Then again, so are traditional law schools. And there's that whole college bubble…

Show Comments (31)