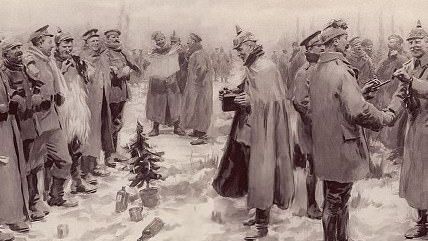

The Christmas Truce of World War I

Recalling the time, 100 years ago, when soldiers refused to fight each other

In his book Silent Night: The Story of the World War I Christmas Truce, historian Stanley Weintraub presented the letters and diaries of the men who temporarily ended WWI for two weeks circa Christmas 1914. One wrote, "Never … was I so keenly aware of the insanity of war."

In the book Weintraub also quotes a 1930 comment delivered by Sir H. Kingsley Wood in the British House of Commons. Wood had been a major in World War I and a participant in the Christmas truce. He went on to become a cabinet minister after the war. Wood noted how many officials now labeled the refusal to fight as "degrading" and unworthy of a soldier. Wood disagreed.

"I … came to the conclusion that I have held very firmly ever since, that if we had been left to ourselves there would never have been another shot fired," he said. The carnage resumed only because the situation was in "the grip of the political system which was bad." Rather than being degrading, the truce was a triumph of shared humanity over the ambitions of empire, something worth remembering 100 years after the fact.

The truce was a series of unofficial and widespread cease-fires that extended over two weeks. The truce between mostly British and German troops centered on the Western Front, defined by lines of trenches that stretched across France from the North Sea to the border of Switzerland. The trenches were often close enough for the combatants to exchange shouted words and to smell food their adversaries were cooking.

Life in the trenches consisted of extreme boredom broken by spikes of terror when an attack was launched. Young men left the comparative safety of their own trenches and crossed open ground into "no man's land" to try to reach the trenches opposite. Even successful attacks racked up huge casualties. The Battle of the Somme in France was waged between July 1 and November 18, 1916, and came to symbolize the cost of trench warfare; more than one million men were killed or wounded. An estimated 12.5 percent of troops on the Western Front died, often from wounds for which antibiotics were not yet available; the casualty rate (both killed and wounded) was estimated at 56 percent. In all, more than 10 million soldiers died in World War I.

It was natural for each side to wonder about the men living so close them who endured the same wretched cold and wet conditions, and who faced the same prospect of an early death. The top brass recognized the danger this curiosity posed to military order. On December 5, 1914, British General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien sent a warning to the commanders of all divisions: "Experience … proves undoubtedly that troops in trenches in close proximity to the enemy slide very easily, if permitted to do so, into a 'live and let live' theory of life…officers and men sink into a military lethargy from which it is difficult to arouse them when the moment for great sacrifices again arises."

Several factors contributed to the danger of "military lethargy." Many of the Germans spoke English well. Weintraub observed, "It is estimated that over eighty thousand young Germans had gone to England before the war to be employed in such jobs as waiters, cooks, and cab drivers." Moreover the British King George V and Kaiser Wilhelm II were both grandsons of Queen Victoria. The fact that the Front conflict occurred on French soil might have also mitigated hostility. Both the British and Germans were European and overwhelmingly Christian, which promoted a veneration for Christmas. Indeed, concerned that Catholics were fighting Catholics, Pope Benedict XV actively sought a Christmas truce in 1914 in order to prevent the "suicide of Europe." Although German officials reportedly entertained the idea, the British did not. But the soldiers may have paid attention.

Meanwhile, powerful factors acted against the likelihood of camaraderie. In the months since WWI had erupted in August, hundreds of thousands of troops had been killed or wounded. Soldiers on both sides had lost friends and witnessed horrible scenes of death and mutilation. Moreover, both sides had conducted massive propaganda campaigns aimed at stirring hatred toward the other.

Against this backdrop, a remarkable thing happened on December 19, 1914. British Lieutenant Geoffrey Heinekey described it in a letter home to his mother. "Some Germans came out and held up their hands and began to take in some of their wounded and so we ourselves immediately got out of our trenches and began bringing in our wounded also. The Germans then beckoned to us and a lot of us went over and talked to them and they helped us to bury our dead." Heinekey could not have been alone in concluding, "I must say they [the Germans] seemed extraordinarily fine men."

Incidents of fraternization kept occurring. A German philosophy student-turned-soldier named Karl Aldag reported that hymns and Christmas songs were being sung in both trenches. German troops foraged for Christmas trees that they placed in plain view on the parapets of their trenches.

By the time Christmas Eve arrived, so much interaction had occurred between the British and Germans that Brigadier General G.T. Forrestier-Walker had officially forbidden fraternization. In his book A Century of War: Lincoln, Wilson, and Roosevelt, Judge John V. Denson quoted the directive. Fraternization "discourages initiative in commanders, and destroys offensive spirit in all ranks. … Friendly intercourse with the enemy, unofficial armistices and exchange of tobacco and other comforts, however tempting and occasionally amusing they may be, are absolutely prohibited."

On Christmas Eve, a hard frost fell. In his book The Truce: The Day the War Stopped, Chris Baker reported on the events of December 24, 1914. "98 British soldiers die on this day, many are victims of sniper fire. A German aeroplane drops a bomb on Dover: the first air raid in British history. During the afternoon and early evening, British infantry are astonished to see many Christmas trees with candles and paper lanterns, on enemy parapets. There is much singing of carols, hymns and popular songs, and a gradual exchange of communication and even meetings in some areas. Many of these meetings are to arrange collection of bodies. In other places, firing continues. Battalion officers are uncertain how to react… ."

Some officers threatened to court-martial or even to shoot those who fraternized, but the threats were generally ignored. Other officers mingled with enemies of similar rank. The Germans reportedly led the way, coming out of their trenches and moving unarmed toward the British. Soldiers exchanged chocolates, cigars, and compared news reports. They buried the dead, some of whom had lain for months, with each side often helping the other dig graves. At its height, unofficial ceasefires were estimated to have occurred along half of the British line. As many as 100,000 British and German troops took part.

On Christmas morning, the dead had been buried, the wounded retrieved and the "no man's land" between the trenches was quiet except for the sound of Christmas carols, especially "Silent Night." In one area, the soldiers recited the 23rd Psalm together: "The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want… ." Soccer and football matches broke out. In some areas of cease-fire, soldiers openly cooked and shared their Christmas meal.

Fraternization continued thereafter but to a diminishing degree, because the high commanders were now acutely aware of the situation and responded with threats of disciplinary action. For one thing, the interaction made many troops doubt if the reports they read in their own newspapers were true. One officer wrote a letter, which was published in the The Daily News on December 30 and one day later in The New York Times. He commented, "The Germans opposite us were awfully decent fellows – Saxons, intelligent, respectable-looking men. I had a quite decent talk with three or four and have two names and addresses in my notebook. … After our talk I really think a lot of our newspaper reports must be horribly exaggerated." These were the first reports on the Christmas truce, because news was suppressed as a threat to "national security."

The English officer Lieutenant A.P. Sinkinson became even more critical of his own government. He wrote, "As I walked slowly back to our own trenches I thought of Mr. Asquith's [British P.M.] sentence about not sheathing the sword until the enemy be finally crushed. It is all very well for Englishmen living comfortable at home to talk in flowing periods, but when you are out here you begin to realize that sustained hatred is impossible."

The atmosphere of goodwill needed to cease. And, so, slowly fraternization was quashed. On New Year's Eve, some singing and shouting of messages occurred, but the truce was over.

Weintraub's book concludes with a chapter entitled "What If?" What if the Christmas truce had continued and soldiers who refused to fight? In summarizing the chapter, Denson comments:

"Like many other historians, he [Weintraub] believes that with an early end of the war in December of 1914, there probably would have been no Russian Revolution, no Communism, no Lenin, and no Stalin. Furthermore, there would have been no vicious peace imposed on Germany by the Versailles Treaty, and therefore, no Hitler, no Nazism and no World War II. With the early truce there would have been no entry of America into the European War and America might have had a chance to remain, or return, to being a Republic rather than moving toward World War II, the 'Cold' War (Korea and Vietnam), and our present status as the world bully."

War is against the self-interest of average people who suffer not only from its horrors but also from its political fallout. Those who benefit from both are the ones who threaten to shoot those who lay down their guns: politicians, commanders and warmongers who profit financially. But even the powerful and the elite cannot always extinguish "peace on earth, goodwill toward men," even in the midst of deadly battle.

Show Comments (60)