In Search of Libertarian Realism

How should anti-interventionism apply in the real world?

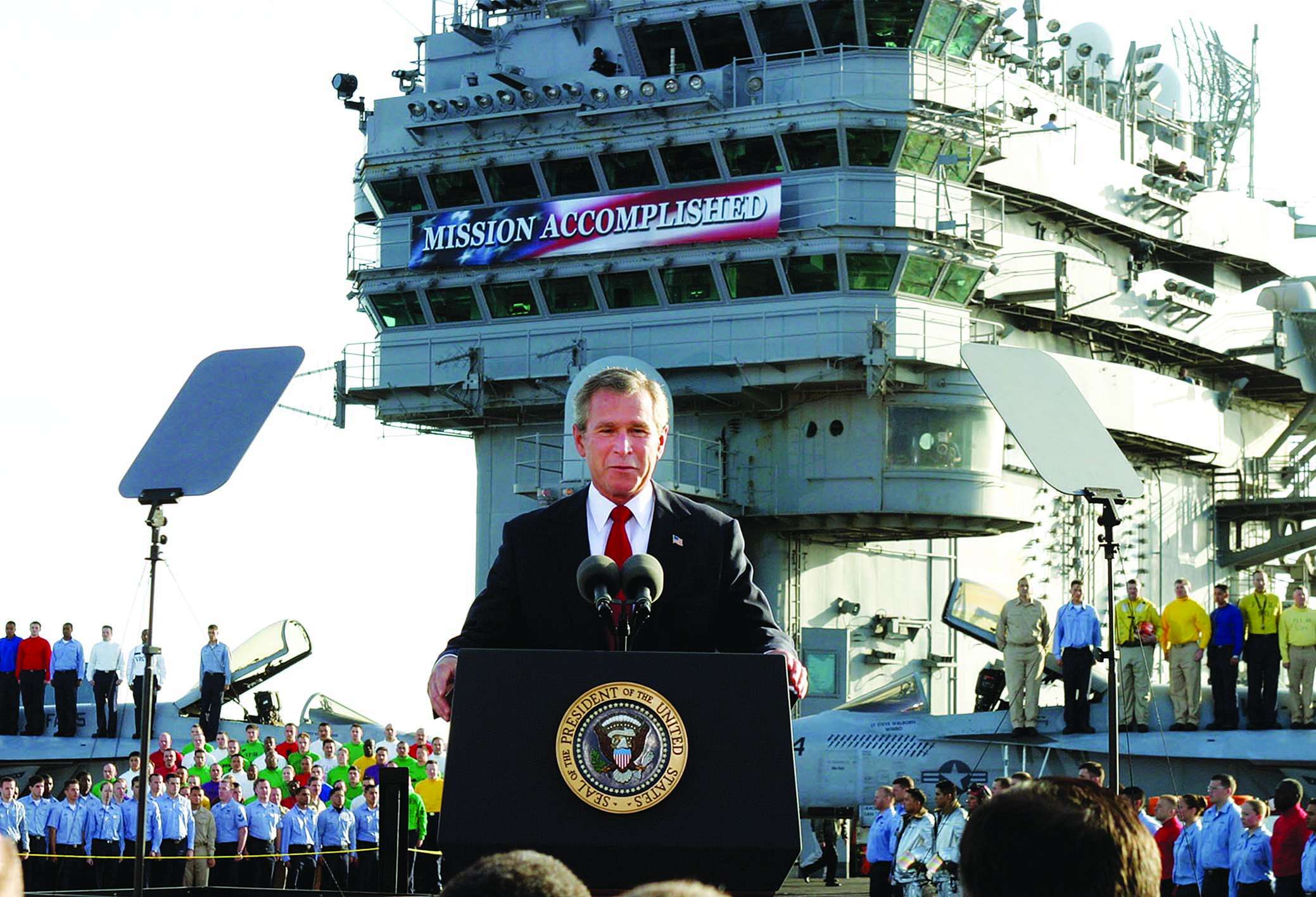

On May 1, 2003, President George W. Bush landed a Lockheed S-3 Viking on the deck of the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln off the coast of San Diego, then delivered a triumphant speech under a banner that read "Mission Accomplished." "In the Battle of Iraq," the president proclaimed, "the United States and our allies have prevailed."

For the next decade, that premature declaration gave way to insurgencies, sectarian warfare, troop surges, corrupt Iraqi governments, 4,000 U.S. combat deaths, even more Iraqi deaths, and $1 trillion in taxpayer money down the drain. The American appetite for war, occupation, and the concomitant surveillance state went on a steady and uninterrupted decline, culminating in the shockingly successful September 2013 public and congressional revolt against President Barack Obama's plans to attack Bashar Assad's regime in Syria. With the occupation of Afghanistan becoming the most unpopular war in recorded U.S. history, and with people telling pollsters they feared their own government more than they feared terrorists, it became possible to imagine a cross-ideological coalition against war, spanning from the progressive left to the constitutional-conservative right, and headed up by the libertarian-leaning Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.).

But 2014 has complicated that narrative. The rise of the Islamic State (ISIS) within war-torn Syria, Iraq, and Libya halted the public's decade-long bear market on war, with more Americans favoring combat troops against ISIS in October than in September, in part because of the Islamic State's horrific beheadings of two U.S. citizens.

Land grabs by ISIS across the region gave rhetorical ammunition to hawks and anti-interventionists alike. The influential camp led by Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) argued that the battlefield successes of ISIS demonstrated the folly of leaving Iraq too soon and of not toppling Assad when we had the chance. McCain's former campaign sparring partner Ron Paul—Rand's father—countered that watching the Iraqi army abandon its weapons after $26 billion worth of propping up by Washington proved the hopelessness of war and nation-building (see "Dr. Never"). Rand Paul, meanwhile, vacillated between those poles, arguing in one breath that the U.S. should "stay the heck out of [Syria's] civil war," and in the next that America should "destroy" ISIS, though only after congressional debate and vote. (For an interview with the younger Paul, see "The Conservative Realist?")

With Rand Paul at or near the top of GOP presidential polls for 2016, the principled noninterventionism of his father is colliding with the complications not just of the Islamic State but of Washington politics. If Ron's project is to spread the pure principles of anti-intervention, Rand's is to see how much anti-intervention he can sneak into the mainstream diet. These differing approaches—and the different men behind them—have triggered all sorts of fierce debates about what a libertarian foreign policy really looks like.

The Hoover Institution's Richard Epstein, in a September piece titled "Rand Paul's Fatal Pacifism," criticized libertarians for being "clueless on the ISIS front," arguing that "In principle, even deadly force can be used in anticipation of an attack by others, lest any delayed response prove fatal." Responding at Antiwar.com, reason Contributing Editor David R. Henderson countered that "whatever else libertarian non-interventionists believe, few of us have what Professor Epstein calls an 'illusion of certainty.' It is the exact opposite: we are positive that there is great uncertainty. It is this uncertainty that should, in general, cause us to pressure our government to stay out of other countries' affairs."

So who's right? And what should libertarian principles about foreign policy look like after colliding with messy reality? In the pages ahead, we have convened a forum of self-identified libertarians who have a range of informed opinions on U.S. foreign policy. The results are designed to start a debate rather than finish it, to take a thoroughgoing skepticism about intervention into the realm of the real. In short, it's a search for libertarian realism. —Matt Welch

The Case for Realism and Restraint

Will Ruger

What role should the United States play in the world? When we ask that question, we are talking about foreign policy: the sum of our defense policy, trade policy, and diplomatic relations with other countries.

The answer: The U.S. should adopt a foreign policy that is both consistent with a free society and aimed at securing America's interests in the world-in other words, libertarian realism. The goal must be to provide security efficiently without sacrificing other important goals that Americans hold in common.

An important caveat up front: There is no universal, one-size-fits-all foreign policy for the ages. A single, comprehensive policy cannot be applied uniformly to any state at any period in history. Geography, institutional constraints, technology, history, and strategic context will always shape how we conduct foreign policy. So the U.S. today might require a very different approach than it needed during, say, the early Cold War or the first years of the republic.

But today, American defense policy should be characterized by strategic restraint; its economic policy must be one of free trade, and its diplomacy ought to be focused on articulating-but not aggressively imposing-liberal values and the benefits of free markets.

Ends and means in politics and war are intimately connected. The primary goal of the state should be to protect the territorial integrity of the United States and the property rights—broadly understood, including throughout the global commons—of the people residing within it. The state is also tasked with securing the conditions that allow for a free people to flourish in America. These elements combine to form the national interest.

The state's role is properly limited to serving these interests rather than meeting the needs of outsiders or of the state itself. However, a libertarian realist foreign policy will have positive benefits for Americans and people of other countries beyond achieving these fairly limited ends.

Realism is important to this schema because, in order to secure our interests properly, we need to understand the world as it is, not as we would like it to be. Realists recognize there are important limiting and complicating factors in politics, just as there are in economics. We can no more wish away the constraints that an anarchic world, the balance of power, and geography impose on statesmen than we can disappear the laws of supply and demand or comparative advantage. We need to understand and adapt to what realism tells us about the laws of international relations.

For example, we might wish we could rely on the rule of law internationally as much as we do domestically, and to maintain a very limited military, if any at all. However, this does not accord with what we've known about international life since Thucydides: The strong often do what they will, while the weak suffer what they must. If you doubt this, look at what is happening in Ukraine.

Realism teaches that power matters significantly in the world, and states can use force to meet a variety of goals, some of them malignant. But even great powers face constraints. As we saw in the Iraq War and aftermath, the world—including the comparatively powerless—also gets a vote, placing limits on what the U.S. can impose. Indeed, the application of power often brings negative unintended consequences and even outright failure.

Ultimately, the long-term security of America rests upon the foundation of a strong economy. Free trade is a key ingredient in the recipe for economic growth, and the U.S. should pursue it maximally. As individuals and firms leverage their comparative advantages in the global economy, the ensuing robust growth will allow Washington to better provide for the common defense at a relatively low cost as a percentage of GDP. There are some rare cases, such as specific strategic goods (missile and weapon technology, nuclear materials, etc.) where trade might be limited on security grounds, but we should be leery of rent seekers who use this rationale as a means to nakedly self-interested protectionism.

In the military realm, the watchword of U.S. policy should be restraint. The restraint approach harkens back to the traditional American thinking about defense that dominated from George Washington's Farewell Address to the beginning of the Spanish-American War in 1898. It finds its most important modern expression in the work of MIT-affiliated scholars such as Eugene Gholz, Daryl Press, Harvey Sapolsky, and Barry Posen, and in the political realm by Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.).

Restraint traditionally has two pillars. First, the U.S. should avoid permanent military alliances and be quite wary of making even temporary commitments in times of peace or war. That will maximize U.S. independence and ensure a free hand to avoid or choose engagements on its own terms. It also means that the U.S. ought to carefully wind down its many security commitments around the globe, including NATO. This pillar of restraint does not rule out wartime coalitions like the one that formed in World War II or that would have emerged after 9/11 to counter our enemies in Afghanistan in the absence of NATO.

Second, the U.S. ought to employ the minimal use of force abroad, consistent with the national interest narrowly defined above. Defense and deterrence will be the primary methods of meeting U.S. security needs. However, this is not the absolute noninterventionism or the functional pacifism often advocated by left-liberals and libertarians. Aggressive military action should be on the table where and when warranted, such as what might have been necessary had the French, in the early 1800s, been unwilling to sell New Orleans and threatened to forcibly close off our trade down the Mississippi. Moreover, defense includes pure pre-emption when necessary, as it was for Israel in the Six-Day War or might be in the future for the U.S. should we have absolutely solid intelligence of an imminent forthcoming attack against American soil or U.S. ships.

Restraint, rooted in realism, requires the maintenance of a very strong—but smaller and more focused—military, with the Navy and the Air Force having the most important roles and the Army sustaining the deepest cuts. Naval and air power will be critical to protect America far from shore should deterrence fail. They also provide power projection capability as needed. But restraint will entail less need for the type of large standing army the U.S. currently maintains around the globe. Of course, a highly professionalized, well-equipped Army (and Marine Corps) will still be needed and ought to be designed for expandability in the event of a significant threat. Restraint also requires a capable intelligence community, though one focused abroad and respectful of American civil liberties at home.

Restraint is particularly well-suited to the realities of the modern world. The U.S. is exceptionally safe today, despite what you see on Fox News or in The Wall Street Journal. The country has an extremely favorable geographic position, with two huge "moats" separating us from strong or threatening powers. It's continent-sized, with plentiful resources, the world's largest economy, and a large, growing population. The neighbors are friendly and comparatively weak, representing zero military threat.

Importantly, the U.S. also has a major military advantage that will remain unrivaled in the decades ahead, even if right-sized in accordance with a restrained realist strategy. Its superior Navy and Air Force together offer an exceptional deterrent capability and the ability to defeat attackers far from our shores. The U.S.'s secure second-strike nuclear capability in particular gives us virtual invulnerability from traditional threats. It is extremely unlikely that any other country would dare attack the U.S. with nuclear weapons or conventional forces.

Of course, the U.S. should be vigilant about the threat posed by explicitly anti-American terrorist groups, especially those that seek to use weapons of mass destruction. However, we also have to be realistic about the danger terrorism poses. It is rarely an existential threat and often best handled by careful intelligence collection, police work, and special operations forces. Nuclear terrorism is also a very unlikely scenario for a variety of reasons, though still something we should guard carefully against.

Appropriately, then, restraint does not a priori rule out the use of military force against terrorist groups and their state supporters when necessary. Afghanistan in 2001 was one such case where war was justified even within a restraint framework, since the regime in Kabul provided a safe-haven for the notorious terrorist group which carried out the deadly attacks of 9/11.

Another virtue of restraint is that the world today, and especially the balance of power, has changed in a way favorable to American security. Our traditional fear, an emergent Eurasian hegemon, is nowhere on the horizon, not least because any attempt at regional primacy will likely be resisted by neighbors and undermined by nationalism. Russia and China, to name two potential rivals, have internal challenges ahead that dwarf our own domestic problems. Lastly, economic and political developments over the last half-century mean that states such as Japan, South Korea, and our current European allies are plenty rich enough to defend themselves individually or as parts of regional alliances. The U.S. is simply not needed to play the central, stabilizing role it did during the Cold War. Indeed, its continuing deep engagement around the globe only makes it less likely that these countries will take responsibility for their own security, thereby releasing American taxpayers from the cost of their defense.

When your ends are "making the world safe for democracy" or other ambitious do-gooderism, your means are going to involve a permanent and expensive military/foreign policy establishment, always primed for aggressive interventionism. More restrained ends require much more limited means.

Restraint's incompatibility with do-gooderism does not mean that realism is immoral or amoral. There is morality to a realistic foreign policy, especially one connected to liberal values. The state acts justly when it serves its citizens' interests and limits itself to things that people would generally favor contracting out to government (foremost among these is protecting the homeland). But a state with an expansive foreign policy can do a great deal of harm in the world, even if its motives are pure.

A limited, realistic foreign policy is much less likely to require means that threaten the purpose of having government in the first place. State action taken in the name of an activist national security policy can have terrible domestic consequences: civil liberty violations, increased militarization of police, an unaccountable and bloated national security apparatus, more debt and larger deficits, and so on.

The United States, thankfully, can afford to pursue a significantly more restrained foreign policy, spending modestly to maintain forces more than adequate for defense and deterrence. We no longer need to support an extensive web of alliances like those of the early Cold War. Instead, the country can rely on its own economic and military strength, along with temporary alliances during wartime, just as George Washington counseled.

To quote John Quincy Adams, the U.S. needs to stop going "abroad in search of monsters to destroy." Humanitarian crises in non-democratic/illiberal regimes do not automatically threaten U.S. interests. Americans should not have to spend their own blood and treasure policing the globe, even assuming that we could do so successfully (which recent history has demonstrated otherwise).

Given that war is the health of the state, and a reliable destroyer of domestic liberty, there are great costs to a free society in maintaining a massive military and using it for anything other than true defense of the homeland. A free society is better off opting for realist-inspired restraint, coupled with economic, diplomatic, and personal engagement with the world.

Libertarianism Means Noninterventionism

Sheldon Richman

A noninterventionist foreign policy is the natural complement to a noninterventionist domestic policy. Even setting aside the formidable anarchist challenge to the very authority of the state, we can see that government is uniquely threatening to liberty and that this threat warrants keeping the state on as short a leash in the international arena as in the domestic arena—or shorter, because foreign policy will inevitably be conducted covertly.

William Graham Sumner, an anti-imperialist classical liberal of the 19th century, noted that intervention translates to "war, debt, taxation, diplomacy, a grand governmental system, pomp, glory, a big army and navy, lavish expenditures, political jobbery." He should have included conscription on the list. James Madison, who was nobody's libertarian, nevertheless got this right: "Of all the enemies to public liberty war is, perhaps, the most to be dreaded, because it comprises and develops the germ of every other. War is the parent of armies; from these proceed debts and taxes; and armies, and debts, and taxes are the known instruments for bringing the many under the domination of the few." He goes on: "In war, too, the discretionary power of the Executive is extended; its influence in dealing out offices, honors, and emoluments is multiplied; and all the means of seducing the minds, are added to those of subduing the force, of the people. No nation could preserve its freedom in the midst of continual warfare."

That constitutes a daunting domestic case against military intervention in the affairs of other countries. But there's more. U.S. government policies and technologies developed to efficiently carry out the occupation of foreign societies eventually "boomerang" on Americans at home, as George Mason University economists Christopher Coyne and Abigail Hall convincingly argue in a paper published in the fall 2014 Independent Review. As the late Chalmers Johnson, author of three books on American imperialism, used to say, we either dismantle the empire or live under it.

On the foreign side, wars and occupations immorally threaten noncombatants, vital infrastructure, and social institutions, sowing the seeds of despotism and humanitarian disaster.

The ambivalence that some libertarians feel toward strict noninterventionism stems, I believe, from faulty thinking about "national defense." Intervention is often presented as defensive in order to conceal geopolitical and economic objectives. Yet some libertarians defend intervention with a simple bully-on-the-schoolyard model: Anyone would be justified in defending a victim and retaliating against a bully. The problem is that we cannot move seamlessly from individuals on a jungle gym to states in the international arena.

States are comprised of individuals, of course, but as the public choice school of economics teaches, these people face vastly different incentives than private citizens do. Governmental decisionmakers can impose the financial and other costs of their policies on a captive population through taxation, regulation, and (potentially) conscription. Those decision makers rarely suffer personally for their misjudgments. The mystique of the nation-state makes many people credulous about and vulnerable to patriotic appeals for support of "their" government and troops in times of crisis. While heroes on the schoolyard are responsible for their actions, essentially irresponsible political personnel have a dangerously broad range of action that is unique in society.

It's tempting to sum up the public choice case for nonintervention by saying that people in the private and political spheres are similarly self-interested, with different incentives leading to different kinds of behavior. But the economist and historian Robert Higgs adds an important amendment: "Whatever its merits as an operating assumption in positive political analysis, the proposition that the people who wield political power are just like the rest of us is manifestly false," he wrote in The Independent Review in 1997. "Lord Acton was not just expelling breath when he said that 'power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.' Nor did he err when he observed that 'great men are almost always bad men'—at least if 'great men' denotes those with great political power. Among the most memorable lines in Friedrich A. Hayek's Road to Serfdom is the title of chapter 10, 'Why the Worst Get on Top.' Hayek was considering collectivist dictatorships when he noted that 'there will be special opportunities for the ruthless and unscrupulous' and that 'the readiness to do bad things becomes a path to promotion and power.' But the observation applies to the functionaries of less egregious governments, too. Nowadays nearly all governments, even those of countries such as the United States, France, or Germany, laughably described as 'free,' provide numerous opportunities for ruthless and unscrupulous people."

The upshot is that even if a well-intended, risk-free interventionist foreign policy could be conceived in the abstract (leaving aside the problem of taxation), its chances of being carried out correctly by any real-world government are virtually nonexistent.

In addition to these incentive and character problems, there is a knowledge problem. Libertarians appreciate the seriousness of this issue in the economic realm: Those who would modify free market outcomes or abolish the market altogether cannot possibly acquire what Hayek called the requisite knowledge of time and place, much of which is tacit. This systemic ignorance guarantees the loss of welfare for society even if the planners have the best intentions.

We find an analogous problem in the managing of foreign affairs. Interfering in a foreign land is likely to bring chaos, thanks to the imperial administrators' ignorance of the target society's complex political, social, religious, sectarian, and tribal dynamics. Invading and occupying another country is like playing Jenga—"the classic block-stacking, stack-crashing game"—while blindfolded and intoxicated. A seemingly innocuous move can produce catastrophic consequences.

There is no better example of these pitfalls than the recent U.S. experience in the Middle East. Before noting some recent lowlights, a word of caution: In viewing the government's record, it can be difficult to distinguish incentive/character problems from knowledge problems. When the same apparent error persists decade after decade, it may not actually be an innocent error, but rather the pursuit of perverse interests. After all, people tend to learn from mistakes. We cannot rule out the possibility that military quagmires represent successful pursuits of geopolitical and economic advantage for particular political and "private" interests.

To pick an arbitrary starting point, in March 2003 President George W. Bush ordered the invasion of Iraq. The intent was to overthrow the government of Saddam Hussein, whom the U.S. government had helped place in power and then later helped to make war on Iran. Officials told the public that decapitating the Iraqi government would not only safeguard Americans—remember those phantom weapons of mass destruction?—but would also win the gratitude of the Iraqis and usher in a liberal democracy.

It did no such thing. With the devil-may-care attitude of that soused Jenga player, the U.S. invasion and occupation plunged Iraq into chaos, which cost many Iraqi and American lives, disrupted Iraqi society, and produced a new authoritarian regime. Nearly a dozen years later, Iraq is threatened by the Islamic State, a violent organization that grew out of Al Qaeda in Iraq, which did not exist before the U.S. invasion.

In Saddam's Iraq, minority Sunni Muslims dominated the majority Shiites (and Kurds) in a secular regime. Was it ignorance or the pursuit of a hidden agenda that accounts for the U.S. policy makers' seeming obliviousness of the Sunni-Shiite divide in Iraq? Why did the U.S. government carry out a pro-Shiite policy pleasing to Iran, the American foreign-policy establishment's favorite bête noire? (That strained relationship is another product of U.S. foreign policy: In 1953, the CIA ousted a democratic Iranian prime minister and reinstated the despotic Shah, which led to the 1979 Islamic revolution and the U.S. embassy hostage taking, producing the Iran-U.S. cold war that persists to this day.)

The Islamic State is in Syria too. That country became prime real estate for an extremist Islamic insurgency the day President Barack Obama and then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton declared Syrian President Bashar al-Assad illegitimate and announced that he "has to go." This set the stage for a bizarre new U.S. war in which Assad's most formidable enemy is now America's target. Whatever our (mis)leaders may say, U.S. ground troops in Syria and Iraq are on the table.

It takes an interventionist foreign policy, devised by ignorant and perfidious politicians, to make such a godawful mess. This does not mean that nonintervention would have brought the world only sweetness and light. To slightly modify Adam Smith: "There's a great deal of ruin in the world." But a free American people (we would have to get free first) could better defend themselves without a global empire, which is both bloody and bloody expensive. At least America wouldn't be creating its own enemies, which is what U.S. foreign policy seems best at doing.

Don't Underestimate the Costs of Inaction

Fernando R. Tesón

Current events in Syria and Iraq have rekindled talk about humanitarian intervention. The amply documented atrocities perpetrated by the Islamic State (ISIS) range from public beheading to rape, forced conversion, and expulsion. The United States and a few other countries are already attacking ISIS from the sky and giving some aid to resistors on the ground. But these bombings will not be sufficient to stop ISIS' crimes. By all appearances, only a full invasion with ground troops could get the job done. And Americans are weary of invasions.

Most libertarians oppose intervention on principle. But let us take a moment to focus not on principles but consequences. Arguments for or against intervention should always consider costs; the problem lies in calculating those costs. We know that every war kills and destroys. We also know that sometimes war produces a positive result. How do we measure and weigh the outcomes?

I do not have enough information to say with any confidence whether the costs of a full invasion to defeat ISIS would be acceptable. But I can propose two guidelines to help policy makers think through the problem.

First, when contemplating military action, leaders should consider the price of inaction as well. Second, the more distant effects—such as future unrest, wars, and massacres—must be evaluated alongside immediate results. These sound like simple things, but they are neglected surprisingly often in public debate over foreign policy.

Here's the tricky part: The effects of intervention, like those of any contemplated human action, have to be evaluated ex ante, that is, from the standpoint of the person who is considering whether to act beforehand, and not only ex post, that is, when all the effects are known after the fact. Especially when you consider that inaction, too, could have led to unforeseen miseries. In other words, hard though it may be to accept, a disastrous outcome is not itself proof that a decision to go to war was the wrong one.

People who defended the 2003 Iraq War (myself included) did not accurately predict all the bad things that the invasion would enable, including the prolonged insurgency and the continued inability of the Iraqi leadership to preserve the gains of Saddam Hussein's ouster. The stronger predictions about the short- and mid-term effects of the war came from noninterventionists, who correctly argued that the invasion would open a Pandora's box in the region. It might therefore be tempting to say that those who make the case for inaction most often (or even always) have the facts (and justice) on their side.

But those who blast the Iraq War are looking at the consequences ex post, that is, after a number of bad things are known to have happened. There's nothing wrong with trying to learn from your mistakes, but it's easy to criticize the Iraq decision in hindsight. If events had unfolded differently—if there had been no Baathist insurgency, if the Arab Spring had consolidated some liberal reform, if the democratic institutions in Iraq had taken root—then we would regard the 2003 invasion differently today. Perhaps betting on those outcomes was foolhardy from the start. But because we are human, we tend to believe retroactively that what actually happened was inevitable and what didn't happen was unlikely. But history is not that linear, and acting as if it is can lead to bad decisions in the future.

So how do we go about measuring the most serious immediate costs of proposed intervention? Defeat is obviously the most costly scenario. Runner-up, arguably, is the killing of civilians. Many wars that might seem justified are nonetheless troubling because they will predictably cause the death of a high number of innocent persons. If there is an acceptable level of collateral damage, then a war that exceeds that level is unjustified because it is disproportionate: The harm caused is greater than whatever good the intervention brings about. If defeating ISIS will bring about the deaths of hundreds of thousands of persons, then many would conclude the United States should not act.

But this way of thinking about consequences may be too narrow. What if military intervention causes great harm now but improves the lives of millions in the future? Even if invading and defeating ISIS would cause a troubling number of civilian deaths, it is possible that failure to intervene would mean death and suffering for millions of more people for years to come. Balancing present certain harm against future uncertain harm is always problematic. But leaders must evaluate the immediate and remote effects of both action and inaction when making foreign policy decisions.

I understand that for the U.S. government, the lives of Americans are more important that the lives of foreigners, and the lives of people alive today are more important than the lives of people who will be born later. This is because the U.S. government has a fiduciary duty to protect its current citizens. But that does not mean that the lives of foreigners are irrelevant in the calculus, particularly when we think about the consequences of inaction.

Consider the genocide perpetrated in Rwanda in 1994. If the U.S. had intervened, at a comparably low cost of American lives and money, maybe 800,000 people would be alive today. Many made a principled case for inaction at the time, arguing that it was not the proper role of the United States to act in other nations' affairs. But the cost in human lives—foreign lives, to be sure, but lives nonetheless—received insufficient weight in the discussion, leading to a bad decision.

Assume for a moment that the United States government had ruled out even air strikes against ISIS over understandable fears of short-term costs. ISIS, in that scenario, would be free to solidify its own totalitarian state. In all likelihood, the chances of war and other ills in the region would increase, because the new state's harsh and expansionist worldview would mortally threaten its neighbors. And it's quite possible that the United States would eventually be dragged into the very war it sought to avoid.

All indications are that the Islamic State would be militantly committed to violent strikes against United States' interests everywhere, including on American soil. If a handful of modestly financed individuals could pull off the 9/11 attacks, imagine the damage that a sovereign state exponentially more rich and powerful could inflict.

As Richard A. Epstein wrote in a September essay for the Hoover Institution, one of the classical functions of government is to defend citizens against foreign aggression. It is thus surprising, Epstein argued, to hear many libertarians "unwisely demand that the United States keep out of foreign entanglements unless and until they pose direct threats to its vital interests—at which point it could be too late." An invasion to defeat ISIS, in other words, might be necessary to defend us effectively against future attacks emanating from the Islamic State. I know that similar arguments were made in the lead-up to the Iraq war. But the fact that those arguments were wrong then (if they were wrong) does not mean they are wrong now.

What are the consequences that the U.S. government can reasonably expect would follow from an invasion against ISIS? There are so many possible scenarios that any prediction would be no more than an educated guess. While some would argue that our lack of information one way or the other is an argument against war, my claim is that there is equally an argument against inaction. Our imaginations necessarily fail to conjure all the ways things might go horribly wrong if we expend American blood and taxpayer dollars on war, but are equally lacking when we try to envision the way things might go wrong if we do not act.

The terrible consequences of inaction are as hard to gauge as the terrible consequences of invading. I confess not to know where the consequential calculus leads. But it is simply false to assert that in the face of uncertainty it is invariably best not to act.

Toward a Prudent Foreign Policy

Christopher Preble

In domestic policy, libertarians tend to believe in a minimal state endowed with enumerated powers, dedicated to protecting the security and liberty of its citizens but otherwise inclined to leave them alone. The same principles should apply when we turn our attention abroad. Citizens should be free to buy and sell goods and services, study and travel, and otherwise interact with peoples from other lands and places, unencumbered by the intrusions of government.

But peaceful, non-coercive foreign engagement should not be confused with its violent cousin: war. American libertarians have traditionally opposed wars and warfare, even those ostensibly focused on achieving liberal ends. And for good reason. All wars involve killing people and destroying property. Most entail massive encroachments on civil liberties, from warrantless surveillance to conscription. They all impede the free movement of goods, capital, and labor essential to economic prosperity. And all wars contribute to the growth of the state.

An abhorrence of war flows from the classical liberal tradition. Adam Smith taught that "peace, easy taxes and a tolerable administration of justice" were the essential ingredients of good government. Other classical liberals, from Richard Cobden and John Stuart Mill to Ludwig von Mises and F.A. Hayek, excoriated war as incompatible with liberty.

War is the largest and most far-reaching of all statist enterprises: an engine of collectivization that undermines private enterprise, raises taxes, destroys wealth, and subjects all aspects of the economy to regimentation and central planning. It also subtly alters the citizens' view of the state. "War substitutes a herd mentality and blind obedience for the normal propensity to question authority and to demand good and proper reasons for government actions," writes Ronald Hamowy in The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. He continues, "War promotes collectivism at the expense of individualism, force at the expense of reason, and coarseness at the expense of sensibility. Libertarians regard all of those tendencies with sorrow."

Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman stated the issue more succinctly. "War is a friend of the state," he told the San Francisco Chronicle about a year before his death. "In time of war, government will take powers and do things that it would not ordinarily do."

The evidence is irrefutable. Throughout human history, government has grown during wartime, rarely surrendering its new powers when the guns fall silent.

Some might claim that a particular threat to freedom from abroad is greater than anything we could do to ourselves in fighting it. But that is a hard case to make. Even the post-9/11 "global war on terror"-a war that hasn't involved conscription or massive new taxes-has resulted in wholesale violations of basic civil rights and an erosion of the rule of law. From Bush's torture memos to Obama's secret kill list, this has all been done in the name of fighting a menace-Islamist terrorism-that has killed fewer American civilians in the last decade than allergic reactions to peanuts. It seems James Madison was right. It was "a universal truth," he wrote, "that the loss of liberty at home is to be charged to the provisions against danger, real or pretended, from abroad."

But surely, some say, the United States is an exceptional nation that serves the cause of global liberty. The United States pursues a "foreign policy that makes the world a better place," explains Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), "and sometimes that requires force, a lot of times, it requires a threat or force." By engaging in frequent wars, even when U.S. security isn't directly threatened, the United States acts as the world's much-needed policeman. That's the theory, anyway.

In practice, the record is decidedly mixed. This supposedly liberal order does not work as well as its advocates claim. The world still has its share of conflicts, despite a U.S. global military presence explicitly oriented around stopping wars before they start. The U.S. Navy supposedly keeps the seas open for global commerce, but it's not obvious who would benefit from closing them—aside from terrorists or pirates who couldn't if they tried. Advocates of the status quo claim that it would be much worse if the U.S. adopted a more restrained grand strategy, but they fail to accurately account for the costs of this global posture and they exaggerate the benefits. And, of course, there is the obvious case of the Iraq War, a disaster that was part and parcel of this misguided strategy of global primacy. It was launched on the promise of delivering freedom to the Iraqi people and then to the entire Middle East. It has had, if anything, the opposite effect.

Libertarians should immediately understand why. We harbor deep and abiding doubts about government's capacity for effecting particular ends, no matter how well intentioned. These concerns are magnified, not set aside, when the government project involves violence in foreign lands.

These doubts are informed by Hayek's observations about the "fatal conceit" of trying to control an economy. Throughout his career, the economist convincingly argued that government is incapable, over the long term, of effective central planning. Attempts inevitably fall short of expectations, because human beings always have imperfect knowledge.

This knowledge problem contributes to unintended consequences. These can be serious enough in the domestic context; they're more serious still in foreign policy. Even well-intentioned wars—those designed to remove a tyrant from power and liberate an oppressed people, for example—unleash chaos and violence that cannot be limited solely to those deserving of punishment. And wars always cost us some of our liberty, in addition to blood and treasure.

For all of these reasons—the expansion of state power, the problem of imperfect knowledge, the law of unintended consequences—libertarians must treat war for what it is: a necessary evil. "War cannot be avoided at all costs, but it should be avoided wherever possible," writes the Cato Institute's David Boaz in Libertarianism: A Primer. "Proposals to involve the United States—or any government—in foreign conflict should be treated with great skepticism." The obviously desirable end of advancing human liberty should, in all but the most exceptional circumstances, be achieved by peaceful means.

The United States is in a particularly advantageous position to adopt foreign policies consistent with libertarian principles. Small, weak countries might not have the luxury of avoiding wars, but the United States is neither small nor weak. Our physical security is protected by wide oceans and weak neighbors, and augmented by the deterrent effect of nuclear weapons. We get to choose when and whether to wage war abroad, and we could do so by assessing the likely costs against the anticipated benefits.

Instead, as the University of Chicago's John Mearsheimer notes, "The United States has been at war for a startling two out of every three years since 1989," and U.S. policy makers show little regard for how such wars advance U.S. security. Large-scale military intervention is usually irrelevant when dealing with non-state actors such as Al Qaeda, and the U.S. government has no magic formula for reordering Iraqi or Syrian politics, the true breeding ground of the so-called Islamic State.

Although there may be occasions when military force is required to eliminate an urgent threat, thus necessitating an always-strong military, our capacity for waging war far exceeds that which is required in the modern world. Despite the ostensible end of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. military's non-war budget remains extraordinarily high. In inflation-adjusted dollars, Americans annually spend more now than we did, on average, during the Cold War, when we were facing off against a global empire with a functioning army and navy, a modern air force, and thousands of nuclear weapons capable of reaching the United States in a matter of minutes. Al Qaeda and all of its copycats combined can't muster even 1/1000th of the destructive power of the Soviet Union.

If the United States used its military power less often, might that be OK for Americans but worse for everyone else? What if the cause of freedom needs the United States as its champion? People living under a tyrant's heel deserve liberation; the threat of U.S. intervention might convince the petty despot to step down; if not, the sharp end of American military power could deliver him to a prison cell, or the gallows.

Such a view unfairly privileges U.S. military power, and the power of the American state, over the power of ideas. Freedom has many champions; it betrays a curious disregard for other freedom fighters' work to suggest that liberty can only flourish under the covering fire of American arms. The question, therefore, isn't whether we should wish to see freedom spread worldwide. The real issue is about how best to do it.

Toward that end, U.S. policies have often been counterproductive, sometimes having the perverse effect of eroding the very concept of individual liberty. Quite a few oppressed people have watched in horror as Iraq has descended into civil war and anarchy. If that is what freedom and democracy look like, they might reasonably conclude, we'll happily opt for something else. Similarly, the United States' entangling alliances with illiberal Arab regimes such as Saudi Arabia make a mockery of Washington's claim to be an advocate for freedom.

This is not an argument against either military power or alliances per se. It is an argument against allowing the world to become overly reliant upon the military power of a single nation. Who's to say, for example, that a more militarily capable European Union would not have proved better able than the United States to deter Russian aggression in Georgia in 2008, and now in Ukraine? Could even modest military capabilities (e.g., a functioning coast guard) better defend Philippine claims to the Scarborough Shoals in their ongoing dispute with China? Might Turkey be fighting the ISIS threat on its border if the Turks didn't believe the United States would do the fighting for them? An international order that is less dependent upon the U.S. military as a vehicle for promoting liberty, and based instead on the presumption that all governments have a core obligation to defend their own citizens, could be a safer one and also a freer one.

Libertarians have traditionally been reluctant to support foreign military interventions. We still should be. We will defend ourselves when threatened. When there is a viable military option for dealing with that threat, and when we have exhausted other means, we may even reluctantly choose to initiate the use of force. Such instances are rare, however, because most of today's threats are quite modest. Libertarians have a very clear sense of the risks associated with military operations. We retain a sober sense of the certainty of unintended consequences and the possibility of failure. We should therefore be skeptical of any claim that preventive war will turn a suboptimal but manageable situation into something much better.

The experiences of the past decade have reaffirmed these truths, and taught us some new lessons, too. Although we marvel at the professionalism and commitment of those who serve in our military, we have been reminded of war's unpredictability, and that the military is always a blunt instrument. Above all, we have learned that the costs of waging wars are rarely offset by the benefits we derive from them.

That does not mean that military intervention is never warranted, or never will be in the future. It does mean that we need to more clearly define those infrequent situations in which war is the last best course of action.

The United States should and will participate in the international system. It must remain engaged in the world. But it is wrong to equate engagement with global military dominance and perpetual warfare. Human liberty exists in spite of, not because of, the power of any one nation, and it is dubious in the extreme to presume that freedom's flame will be extinguished if the United States adopts a more discriminating approach toward the use of force.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "In Search of Libertarian Realism."

Show Comments (57)