Crazy U.K. Copyright Laws Suppress WWI Soldiers' Letters, Other Historical Documents

How the U.S. and Britain can learn from each other to make unpublished and orphaned works available to the public.

This year is the centenary of the beginning of World War I. Visitors to the Imperial War Museum, the National Library of Scotland, the University of Leeds, and other sites have the chance to view special exhibitions associated with the historical event.

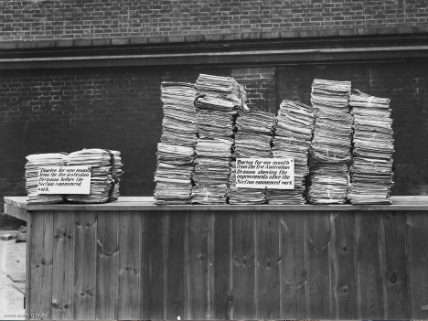

In each of the displays, several cases are empty. The reason? Museums and libraries wanted to showcase letters from soldiers, but these letters were never published. As a result, according to U.K. copyright law, they will not be in the public domain until 2039.

The empty display cases are part of a Free Our History campaign, organized by the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals [cilip], which is attempting to alter laws regarding unpublished works in the U.K. According to cilip, more than half the archival documents in the U.K. are copyrighted by persons who can't be identified, rendering them "orphan" works. The Imperial War Museum has 1.75 million such documents.

It may seem ridiculous that 100-year-old letters cannot be displayed by public institutions in Britain for another quarter century, but the problem goes beyond that. Currently, any unpublished work, no matter how old, is protected until 2039. Naomi Korn, Chair of the Libraries and Archives Copyright Alliance, said that even medieval manuscripts held by the British Library may be under copyright. Institutions may not be able to display documents related to the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo next year. Unpublished letters by Arthur Conan Doyle are embargoed, even though his published works are now in the public domain in the U.K. According to Klein, because these works are "still under copyright protection they cannot be displayed without the museum, library or archive seeking permission from the rights holder or spending time and money trying to trace rights holders and taking out an unnecessary Orphan Works License. In this way the delay to much needed government reforms of copyright law limits and distorts the telling and understanding of our nation's history."

So how could U.K. law be changed to allow museums to display these works? One solution—perhaps surprising—would be to bring the law more in line with current U.S. copyright terms.

Anyone familiar with copyright law in the U.S. knows that our American regime is byzantine, restrictive, and generally awful. But in this one instance, it functions better than European and British copyright, according to David R. Hansen, professor and librarian at the University of North Carolina School of Law.

Hansen told me that the "first sale" doctrine allows libraries, museums, and non-profit institutions to display unpublished orphan works with minimum legal risk. "After the first sale," Hansen explained, in the U.S. "anyone who owns that particular copy of it can display it afterwards."

Beyond that, American copyright law—unlike British law—includes strong and relatively flexible fair use provisions, which makes it easier for non-profits to not only display work, but also to digitize it.

There are difficulties in the U.S. in dealing with unpublished and orphan works, but those difficulties are somewhat different than those faced by U.K. libraries and museums. To begin with, the definition of "unpublished" is clearer in Britain than it is in the U.S., which means that in America it can be harder to determine whether that small-circulation book was published or not, and then harder still to figure out if it's out of copyright or in public domain.

Beyond that, Hansen said, U.S. artists working in a for-profit setting don't have as much fair use protection as non-profits and scholarly institutions. Non-profits are in most cases protected from damages. If they digitize something and the creator turns up, the worst that would happen in most cases is that they would have to take the piece offline. A for-profit documentary filmmaker who incorporates an old film clip by an unknown creator, on the other hand, can face serious statutory penalties ($150,000 fines in some cases)—and of course the documentary film could be ruined if the original creator demands the removal of the clip. In this respect the U.S. could probably benefit from a system of licensing, perhaps similar to the one involving cover songs, where the creator cannot prevent use, but is owed a flat fee, which could be claimed if the creator of an orphan work suddenly appeared. As it happens, a licensing scheme along these lines has just recently been established in the U.K.—though it's time-consuming and expensive, and doesn't provide much relief for research institutions with thousands or millions of orphan documents in their collections.

The other major problem in the U.S. is simply that the law is so complicated, and new uses so unexplored, that institutions will sometimes shy away from exercising rights they actually have. Scholarly publishers in comics studies, for example, often won't reprint panels without permission from DC or Marvel, even though there is a strong fair use argument for doing so. Similarly, libraries and archives may be leery of presenting or reproducing unpublished works because there hasn't been a lawsuit dealing with the issue yet. "Libraries and archives…have to get comfortable with taking some risks and asserting rights that they have to start to move forward with digitizing these things," Hansen said.

Martin Paul Eve, author of the forthcoming Open Access and the Humanities, characterized re-use of orphan and unpublished works as "a victimless crime"—no one is hurt when you display or digitize a centuries-old letter by a forgotten author. Suppressing such a letter, however, restricts public understanding and scholarly research. The U.K. and the U.S. can both do better in making these works available—in part, perhaps, by learning from each other.

Show Comments (31)