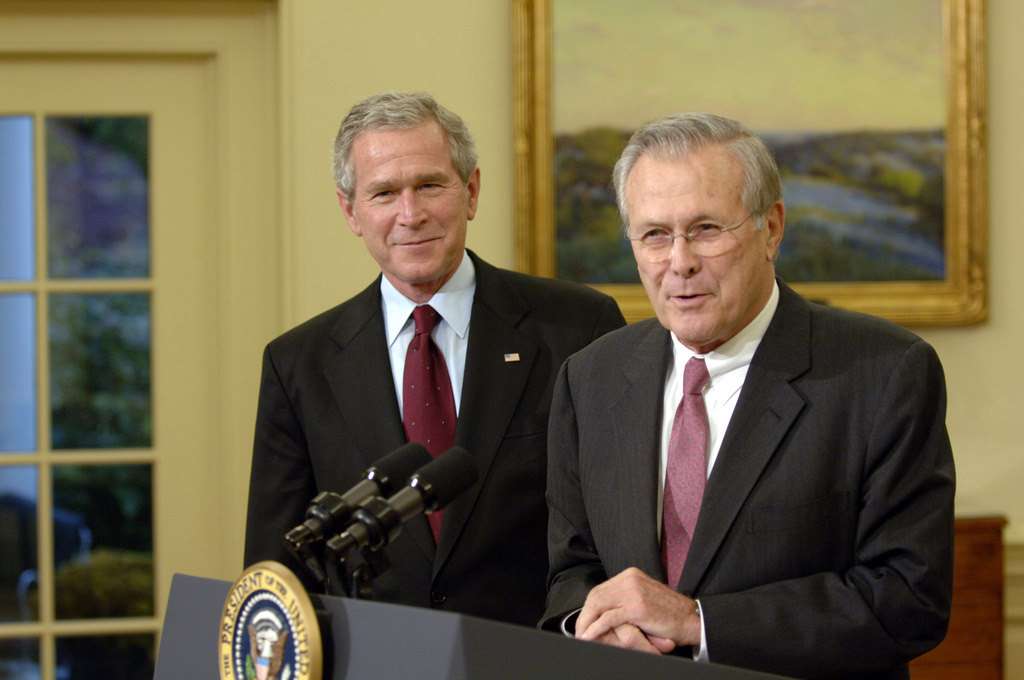

American Forces Found 5,000 Chemical Weapons In Iraq—Just Not the Ones the Bush Administration Claimed Were There

There were thousands of chemical weapons in Iraq, some of which harmed Americans, according to a lengthy new investigative report in The New York Times—and the public, members of Congress, and even members of the military were misled about their existence. Nor were they the chemical weapons that the Bush administration said the U.S. was going after when it attempted to justify the military operation that became the Iraq War.

According to the report, American troops and Iraqi allies found roughly 5,000 chemical weapons in various forms, including a single depository of about 2,400 warheads, between 2004 and 2011. In six separate instances, American troops or allies were wounded by the weapons. The New York Times managed to get in touch with 17 American troops, as well as seven Iraqi cops, and talk to them about the experience. The military says there were at least a few more who were injured by the hushed-up chemical arms, but won't say exactly how many.

These were not products of the active, ongoing chemical weapons program that the Bush administration claimed existed and had to be stopped when it first made the case for war in Iraq. All the weapons were all more than a decade old by the time they were discovered. Most were made in the 1980s, and every single one of them had been created before 1991.

The Times says flatly that "the discoveries of these chemical weapons did not support the government's invasion rationale."

Their existence was a closely kept secret, even within the government. As the Times notes:

Since the outset of the war, the scale of the United States' encounters with chemical weapons in Iraq was neither publicly shared nor widely circulated within the military. These encounters carry worrisome implications now that the Islamic State, a Qaeda splinter group, controls much of the territory where the weapons were found.

The American government withheld word about its discoveries even from troops it sent into harm's way and from military doctors. The government's secrecy, victims and participants said, prevented troops in some of the war's most dangerous jobs from receiving proper medical care and official recognition of their wounds.

Soldiers who were aware of the discoveries were ordered to keep quiet about them, and even to mislead Congress about what they knew. "'Nothing of significance' is what I was ordered to say," retired Army Major Jarrod Lampier tells the Times. Lampier was on site when the biggest chemical weapons dump, containing 2,400 warheads, was found.

The secrecy compounded the dangers posed by the weapons, creating a cascade of failures:

In case after case, participants said, analysis of these warheads and shells reaffirmed intelligence failures. First, the American government did not find what it had been looking for at the war's outset, then it failed to prepare its troops and medical corps for the aged weapons it did find.

Why didn't the government reveal their existence? Possibly because they were embarassed that they were wrong, or perhaps because in some cases the U.S. and some of its Western allies had played a role in designing or creating the weapons in the first place:

Participants in the chemical weapons discoveries said the United States suppressed knowledge of finds for multiple reasons, including that the government bristled at further acknowledgment it had been wrong. "They needed something to say that after Sept. 11 Saddam used chemical rounds," Mr. Lampier said. "And all of this was from the pre-1991 era."

Others pointed to another embarrassment. In five of six incidents in which troops were wounded by chemical agents, the munitions appeared to have been designed in the United States, manufactured in Europe and filled in chemical agent production lines built in Iraq by Western companies.

All in all, it looks like the revelation of another colossal failure in what is already widely recognized as a colossal failure of a war. (But hey, if at first you don't succeed, try and try again.)

Show Comments (227)