Parallels Between Iraq and Vietnam

The only thing we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history.

A corrupt government that has alienated many of its people finds itself unable to overcome a growing insurgency in an endless civil war and expects a superpower on the other side of the globe to come to its rescue. That's the story in Iraq today—which carries eerie echoes of the not-so-distant past.

In June of 1964, as conditions deteriorated in South Vietnam, President Lyndon Johnson assured a journalist he was not about to get too far in or stay too far out. "We won't abandon Saigon, and we don't intend to send in U.S. troops," he insisted. He was betting that U.S. military advisers would be enough to head off defeat.

Half a century later, President Barack Obama has adopted a similar policy, dispatching some 300 advisers to Iraq in an effort to keep its military from being routed. Once again, the fervent hope in the White House is that a small commitment will suffice.

The difference is that Obama's decision comes in the aftermath of a catastrophic American intervention, following our departure, rather than at the beginning of one, as we're about to plunge in. It's an epilogue, not a foreword.

But the parallels between the two wars are more conspicuous than ever. And there are clear morals to be drawn from them. Some of the big ones:

- Military power is overrated. The United States had huge advantages in technology, resources and manpower over the North Vietnamese and their Vietcong confederates. Our soldiers prevailed again and again in combat. But victory eluded us.

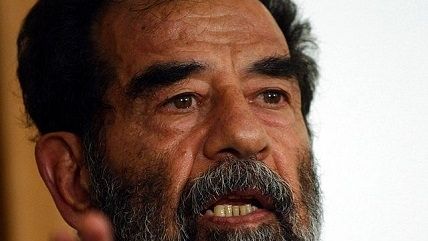

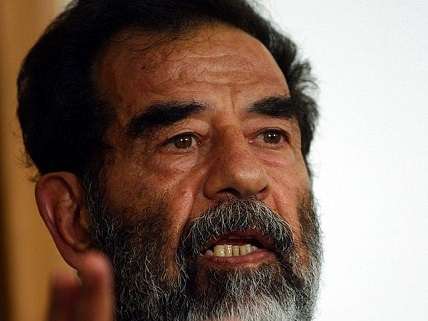

- Same in Iraq. We smashed Saddam Hussein's army with devastating speed. But we were unprepared for the subsequent guerrilla war, fought with improvised explosive devices and suicide bombs. The insurgents had no chance of defeating American units in conventional battles. But they didn't need to.

- Motivation is critical, and we can't supply it to our allies. The U.S. spent some eight years and $25 billion training the Iraqi military, which greatly outnumbered the fighters of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). But when ISIS launched an offensive this month, the government forces dissolved like sugar cubes.

- The militants have succeeded despite many disadvantages. They have one big advantage, as an Iraqi commander told The New York Times: "ISIS fighters have a will to die, so they don't show fear."

- The same was true of the enemy in Vietnam. Our South Vietnamese allies were notoriously unreliable, while Communist soldiers fought doggedly despite horrendous conditions. "'I wish they were on our side' was a comment commonly uttered by American officers," wrote Stanley Karnow in "Vietnam: A History."

- Once American forces were gone, the North Vietnamese mounted a campaign aimed at winning the war in two years. It took less than two months.

- You can't implant democracy in barren soil during wartime. We tried in both places, and in both places, what emerged was an autocratic regime far more intent on holding on to power by force than building broad popular support.

- South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu's regime fell partly because it had shallow roots among the people. Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki's Shiite government fostered fear and loathing among the Sunni minority. The military debacles were the fruit of their political failures.

- You can't outlast a homegrown opponent. The problem with overseas wars is that the enemies are in their own country. They don't have to search for reasons to fight: They fight because their land has been invaded.

- They also don't have to win—they only have to hold on. Eventually, Americans will leave, because they can. Leaving is not an option for those we are fighting.

The lessons of Vietnam were seared into the minds of many Americans, but by 2003, they had faded. Iraq, not to mention Afghanistan, proved their lasting applicability.

"The United States spent more on the Iraq war in real terms than it did on the Vietnam War," notes MIT defense scholar Barry Posen in his formidable new book, "Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy." "Though military analysts believe that the (Communist) Vietnamese were much more competent militarily than the Iraqi insurgents, the Iraqi insurgents appear to be twice as efficient killers."

Maybe the Iraq debacle will inoculate future presidents against large land wars on foreign continents. So far, though, it has confirmed the adage that the only thing we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history.

Show Comments (139)