E-Cigarettes Are Bad Because They Look Like Cigarettes; E-Hookahs Are Worse Because They Don't

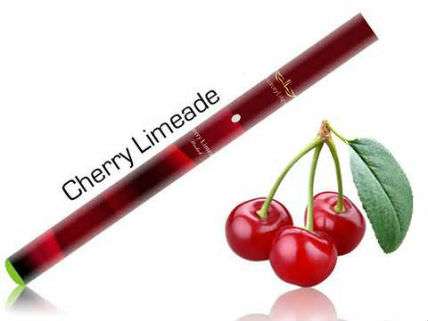

The main rap against e-cigarettes, as summarized by the Los Angeles Times in its story about that city's brand-new ban on vaping in public, is that they look so much like the real thing that they could "make smoking socially acceptable after years of public opinion campaigns to discourage the habit," thereby "undermining a half-century of successful tobacco control." By contrast, the main rap against e-hookahs, as explained by The New York Times today, is that they are "shrewdly marketed to avoid the stigma associated with cigarettes of any kind." They do not look like hookahs, but neither do they resemble conventional cigarettes, since these vapor-emitting cylinders "come in a rainbow of colors and candy-sweet flavors." In fact, they are so distinctive in appearance and branding that people who buy them do not necessarily identify themselves as e-cigarette users.

Why is that a problem? Apparently because this fuzziness about the name of the product makes life more complicated for social scientists:

The emergence of e-hookahs and their ilk is frustrating public health officials who are already struggling to measure the spread of e-cigarettes, particularly among young people. The new products and new names have health authorities wondering if they are significantly underestimating use because they are asking the wrong questions when they survey people about e-cigarettes.

Is there any other objection to e-hookahs? "Beneath the surface," the Times warns, "they are often virtually identical to e-cigarettes, right down to their addictive nicotine and unregulated swirl of other chemicals." That "unregulated swirl" sounds scary, but the components of e-cigarette vapor—mainly propylene glycol and water, plus nicotine and flavoring—are vastly preferable to the complicated mixture of toxins and carcinogens generated by burning tobacco. The Times offers no evidence that e-cigarettes, by whatever name they are called, pose a significant hazard to consumers or bystanders.

So what are those "public health officials" worried about, aside from the need to revise their survey questions? The Times says they worry that calling e-cigarettes "e-hookahs," "vape pipes," "vape pens," or "hookah pens" instead of e-cigarettes "will lead to increased nicotine use and, possibly, prompt some people to graduate to cigarettes." The logic here eludes me: People who are attracted to e-hookahs because they want nothing to do with smoking will change their minds because…?

Although many smokers have switched to vaping, the Times, which is running a series on e-cigarettes, does not seem to have located a single example of a vaper who switched to smoking. As far as I know, neither has any other news outlet. Although that transition is theoretically possible, the evidence suggests it is not very common. The recent increase in vaping among teenagers has been accompanied by a continued decline in smoking, and in a 2013 survey of 1,300 college students, only one respondent reported vaping before he started smoking. The lead researcher said "it didn't seem as though it really proved to be a gateway to anything."

To sum up: E-cigarettes are bad because they look like cigarettes. E-hookahs are worse because they don't. Using either of them might lead to smoking, although we can't find any real-life examples of that. Fruity flavors show these products are aimed at children—or maybe at young women, middle-aged actresses, or old Arab men. But the point is, they are aimed at somebody, and the companies selling them clearly are trying to make them appealing, which cannot be tolerated.

Show Comments (19)