How Long Would Limited Strikes In Syria Stay Limited?

What, exactly, would the White House hope to accomplish with an attack on Syria? So far, the answers from the administration have been pretty vague.

In an interview with PBS yesterday, Obama said that "if, in fact, we can take limited, tailored approaches, not getting drawn into a long conflict" those actions might serve as "a shot across the bow saying, stop doing this." Obama further suggested that the limited actions under consideration "may have a positive impact on our national security over the long term and may have a positive impact in the sense that chemical weapons are not used again on innocent civilians."

That Obama will only say they "may" implies he knows that they may not. One reason to be suspicious is that it's unlikely that the U.S. would be able to take out Assad's chemical weapon stockpiles using the limited strikes that Obama has hinted at so far. Those stockpiles are often buried in protected facilities, making them difficult to destroy from the air.

And that assumes we can even find them. As the Associated Press reported yesterday, "Intelligence officials say they could not pinpoint the exact locations of Assad's supplies of chemical weapons, and Assad could have moved them in recent days as the U.S. rhetoric increased." Which creates an additional risk. "That lack of certainty means a possible series of U.S. cruise missile strikes aimed at crippling Assad's military infrastructure could hit newly hidden supplies of chemical weapons, accidentally triggering a deadly chemical attack."

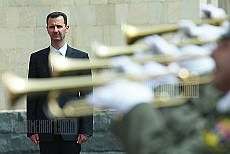

One thing it's clear that limited strikes wouldn't do is stop Syria's dictator Bassar al-Assad's regime from continuing to kill Syrian civilians. If the United States chose to respond, he told PBS, "that doesn't solve all the problems inside of Syria, and, you know, it doesn't, obviously end the death of innocent civilians inside of Syria."

What so-called limited strikes would do, however, is put the United States on the road to further, not-so-limited military action. Obama says he does not want to get "drawn into a long conflict," but what happens if there are further chemical weapon attacks—in Syria, or, eventually, somewhere else in the world? Presuming that chemical weapons were used in the most recent attack, and that they were used with Assad's approval, then we know he has already risked international military reprisal once. There's little reason to think that a round of limited strikes would convince him not to do it again. Assad would essentially be in the same position he was in before. We, meanwhile, would have taken military action—and picked a side in an ugly, bloody civil conflict.

And if Assad deploys chemical weapons again, then what? Another round of "limited" strikes? And after that, another? How long before those limited strikes evolved into something more expansive? As Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Martin Dempsey told NPR last month, "Once we take action, we should be prepared for what comes next. Deeper involvement is hard to avoid." The best way to do so is to stay out of the conflict entirely.

Show Comments (48)