Artifact

Dirty Secret

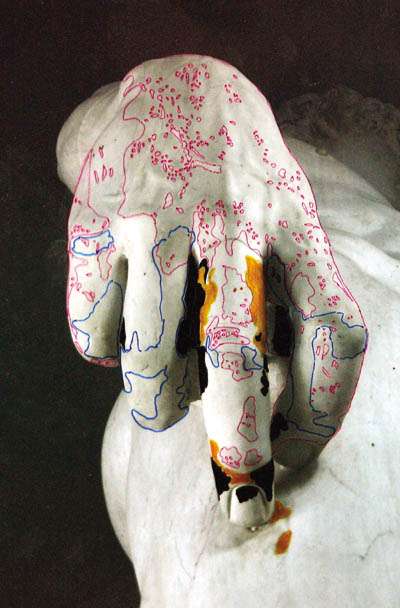

Here's the right hand of Michelangelo's David; those colored spots and lines mark the cracks, blemishes, and grime that have accumulated over 499 years. David's flaws have been digitally mapped in preparation for his first cleaning since 1843, when he was bathed in hydrochloric acid. That won't happen again, but the question of how to clean him remains contentious, as does the issue of whether to clean him. One unhappy critic thinks that cleaning David is "a stripping-away of history," that grime and cracks are "the natural marks of time."

This debate breaks out every time an iconic work comes up for restoration. Critics of the Sistine Chapel, cleaned in an extensive project that ended in 1994, think the colors are now much too bright. Leonardo's Last Supper, many believe, was destroyed by a restoration completed in 1999. Mona Lisa may be the world's grimiest image, but nobody dares wipe the thing down.

It's true that the flaws of age are marks of time. It's also true that cultural meaning is often rooted in its materials. Change a work's material by revealing its original colors or gleam, and you risk altering its present meaning as well. A restored Sistine Chapel may be closer to Michelangelo, but it's further from us. Michelangelo made David, but we decide what it means.

Show Comments (1)