Trends

How the Well Is Running Dry on OPEC's Cartel

Cartels, free-market economists have long maintained, cannot last unless propped up by governments, because they have no way to enforce their agreements to limit supplies and keep prices high. Members "cheat," and the cartel falls apart, a victim of market forces and human nature.

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), however, seemed to many observers a counterexample to economic doctrine. With average annual oil-price increases of 32 percent during the '70s, the cartel seemed invincible.

Since 1980, however, OPEC has been in decline and now appears to be gasping its last breath. "It has taken a while to get there," Fortune writer Daniel Seligman recently observed, "but OPEC is now a solid textbook case of why cartels come apart."

The 13-member organization's imminent disintegration, in fact, is occurring "in ways predicted by cartel theory," Seligman noted. "Years of holding prices at monopoly levels have reduced consumption, brought an avalanche of new production into play, and triggered boundless chiseling by cartel members fighting for their shares of a shrinking market." Reacting to the ever-escalating OPEC price—which peaked at $36 per barrel in 1980 (and stands at $28 in mid-1985)—global oil consumption has dropped 20 percent since 1979, as users either learned to conserve or switched to other, less-expensive fuels.

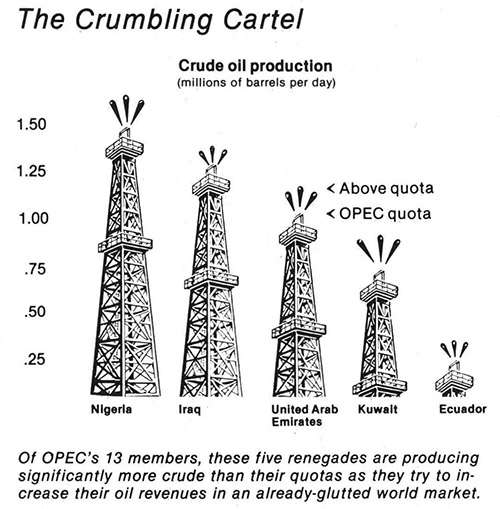

Meanwhile, non-OPEC oil-producing countries increased their production to harvest profits from the high prices. And as prices began to fall, several OPEC members—Nigeria, for instance—began producing more than their agreed limit and selling it for less than the official OPEC price.

Saudi Arabia, the cartel's leader, has been playing the patsy to the organization's cheats, cutting back its own production to half its authorized quota of 4.3 million barrels a day to make up for overproduction by others. But the country is nearing its breaking point, for its low level of production has brought its real oil income down to almost one-tenth of its former high. This fiscal year, Saudi Arabia will likely have the largest government deficit—$20 billion—in the world after the United States. Salaries have plummeted, and people are leaving the country in droves—50,000 a month according to a recent Wall Street Journal report.

The Saudis now face tough choices, a situation brought about by the very nature of the cartel. As S. Fred Singer, an economist at George Mason University, recently observed in the Wall Street Journal, the Saudis have essentially three options: (1) lowering the price of their oil and increasing production, a move Singer describes as "politically risky" for the Saudis, because "it would hurt energy producers geographically close to Arabia, including Iran, Iraq, Libya and Egypt"; (2) keeping their production level low and reducing the price only slightly, which "would simply keep the oil glut going" and put more downward pressure on prices; and (3) initiating an all-out temporary price war, in hopes that wayward OPEC members will see the light and come back into the fold.

How would crashing oil prices affect the world generally? Though there certainly would be economic casualties—heavily indebted Third World nations, for example, that rely on their oil exports to make loan payments—"the benefits of cheaper oil swamp those negatives," as Fortune writer Aloysius Ehrbar recently put it. With plummeting oil prices, for instance, gasoline prices would turn down as well, saving millions for consumers, and airlines and their passengers would similarly benefit from a drop in plane-fuel prices. "Cheaper oil would gradually work through to the prices of chemicals, plastics, synthetic fibers, toys, sailboats, and millions of other products," Ehrbar observed, and eventually stimulate "a drop in short-term interest rates that should accompany a decrease in inflation."

The lesson to be derived from OPEC's demise is not that cartels can wreak no havoc (obviously, they can), but that they cannot elude the forces of the marketplace—even without antitrust laws to break up such combinations.

It's a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood

Mad as hell about inefficient and intrusive government but don't know what to do about it? Have we got an idea for you: start a "self-assessing homeowners' association."

Don't be put off by the daunting title. A new report prepared by the Washington, D.C.–based Sabre Foundation for the Joint Economic Committee of Congress details the purpose and practice of these innovative organizations. It also recommends several steps that federal, state, and local governments can take to encourage the formation of homeowners' associations and "neighborhood development organizations."

Homeowners' associations are composed of property owners who band together and provide neighborhood services that are usually provided by government—such as street maintenance and lighting, snow removal, trash collection, fire protection, and transportation. Because association members enter into deed-based agreements to share the costs of these services, the enthusiasm burnout and spotty participation that plague many other voluntary civic organizations are not problems.

What good are homeowners' associations? The Sabre Foundation report notes that they are able to pick and choose among various service contractors—garbage collectors, for instance—thus saving members money. In addition, most associations require that property be kept in good repair, which prevents neighborhood physical deterioration and keeps property values up. Increased neighborhood-watch activities, usually required by property deeds, reduce crime rates and further serve to increase property values.

Nothing begets imitation like success. In the last two decades the number of homeowners' associations has skyrocketed from 500 to more than 25,000. Most are located in new subdivisions and new communities where developers require membership in the association as a condition of sale. Homeowners' associations are a good deal for middle- and upper-income neighborhoods, but they are not common in poorer areas. That's where neighborhood development organizations (NDOs) come in.

NDOs furnish social services—low-income housing, job training, day-care services—to disadvantaged members of the community. Unlike homeowners' associations, they do not rely on property-owner dues. Until recently, most were financed by federal grants and philanthropic foundations. But creative NDOs have begun to raise money by buying and developing real estate—some NDOs are raising as much as $400,000 yearly in this manner. The organizations can then finance social services that would otherwise be billed to the beleaguered taxpayers.

Sounds neat? Well, there are a few flies in the ointment. Tax policy, for one thing. Many homeowners' association members are floored by a double whammy—they pay association dues to finance certain neighborhood services yet must also pay the usual local taxes for municipal services they've opted out of. The Sabre Foundation recommends that localities follow the examples of Houston, Texas, and Kansas City, Missouri, which extend tax rebates to homeowners' associations that provide their own refuse collection.

To encourage homeowners to join new associations, the Foundation suggests that governments offer "challenge grants." These grants would usually be in the form of tax relief to association members once a specified percentage of a neighborhood's residents sign up.

A third recommendation, intended to wean NDOs from public support, is for governments to transfer idle public property to NDOs, which can develop the properties and use the proceeds to become self-supporting.

The Sabre Foundation report gives clear evidence that homeowners' associations and neighborhood development organizations can save taxpayers money, reduce the size of government, and promote community self-sufficiency. Now that's a good deal. Power to the neighborhoods!

The FDA Delivers a Dose of Common Sense

When the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently declined to ban 10 food dyes, it challenged the sanctity of one of the sacred cows of the regulatory state: the Delaney Clause. The FDA had been petitioned to ban the dyes under the Delaney Clause by self-styled consumer advocate Sidney Wolfe's Health Research Group (REASON readers were introduced to Wolfe and HRG in "It's Effective—But Is It Safe?" March 1985).

The Delaney Clause is a perfect example of government good intentions run amok. Enacted by Congress in 1958, the provision bans any substance used in commercial food processes if that substance has been shown under any circumstances to cause cancer in animals or man. It sounds reasonable, but in practice the clause has been used to ban substances no matter how small or questionable the risk of cancer. And it lets bureaucrats make decisions for individuals—such as whether or not to use products such as saccharin.

FDA Commissioner Frank Young explained that the commission's rejection of the food-dye petition was based on the legal concept of de minimis—that the law does not concern itself with trifles. The cancer risk posed by the food dyes in question is so minimal, ruled the FDA, as to be immune from the Delaney Clause by the de minimis standard.

Consumerists were livid at the decision, which marked a new turn at the FDA. "It's as brazen an evasion of the law as anything we have seen during the Reagan administration," gasped Rep. Ted Weiss (D–N.Y.). Sidney Wolfe charged that the FDA's philosophy of regulation is a throwback to "an era before the 1900s, when industry was self-regulatory." The Wall Street Journal had a more restrained and more sensible response. "Every bureaucrat and congressional staffer in town," editorialized the paper, should carve "two useful words into his desk as the capital's new motto: De Minimis."

You Can't Drive Away From the Price You Pay

The federal government prohibits tolls on all but a few special segments of the Interstate Highway System. (One notable exception is New York's Thruway, which was built by issuing state bonds in the early 1950s.) The purpose of this prohibition is to keep the interstate system "free." But as we learn every time we drive up to the gas pump or buy a new tire for our 18-wheeler, there ain't no such thing as a free lunch. The great virtue of toll roads is that those who use 'em pay for 'em, making for more economic decisions on the part of both road builders and road users.

Since the Interstate Highway System was created in 1956, construction and maintenance of the 42,000-mile network of roads has been financed by the Highway Trust Fund, which raises about $11 billion annually through taxes levied on gasoline, tires, tubes, and truck parts. Today, with more than 98 percent of the interstate built, the Highway Trust Fund goes toward maintaining the system.

Every few years someone notices that the revenues raised by the trust fund can't keep pace with the construction and repair costs of the interstate, so political Washington responds in the best way it knows how—by raising taxes. (The last increase was in 1982, when "our decaying infrastructure" was saved by jumping the federal gas tax from 4¢ per gallon to 9¢ per gallon.) Transportation analysts are now predicting that the fund will run dry by 1990 unless Congress jacks up the gas tax by another 2¢ per gallon. But an alternative to a tax hike is being bandied about our nation's capital these days—toll roads.

The push for tolls is coming from the Transportation Infrastructure Advisory Group (TIAG), a coalition of primarily business organizations that is promoting tolls as an alternative to tax increases as a method of financing interstate repairs. Founded just over a year and a half ago, TIAG is helping to change the terms of debate in the Washington transportation community. TIAG Project Coordinator Donna Marshall Constantinople told REASON that while they were a nonissue until very recently, "today toll roads are on the agenda and are being talked about." Sen. Lawton Chiles (D–Fla.) has introduced legislation embodying TIAG's proposal.

Public resistance to new taxes may be sparking a toll road renaissance. As BASIX Corporation Chairman Donald T. Beldock, a founder of TIAG, recently asserted in Financier, "The pendulum is starting to swing back" from tax-financed public works to user fees, and "tolls as a funding source are once again gaining popularity." Skeptics need look no farther than to northern Virginia for evidence of this trend—Washington, D.C., is now linked to Dulles International Airport by the capital's first toll road.

A new toll road is also being built in DuPage County, Illinois. Even California, which has a long history of stubborn opposition to toll roads, is taking a closer look. "I think it would be worthwhile for California to realize what the rest of the country is talking about," remarked a Bay Area transportation official recently.

Altering public policy is often a slow, fitful process. The first step is to get policymakers to listen to your ideas and to take them seriously. Toll roads advocates are making good progress on that first front.

There's "Private" Deposit Insurance, and Then There's Private Deposit Insurance

Financial Institutions Assurance Corp., founded in 1967 in North Carolina, insures the deposits of 68 savings institutions in four states. A FIAC-insured institution has never gone belly-up. This is not extraordinary news, but it is noteworthy; for FIAC is a completely private deposit-insurance company—a kind of entity that many say can't work. To these critics, only some form of government-provided insurance will do, such as the predominant federal system that includes two main institutions, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corp.

Skepticism about private deposit insurance was in much evidence earlier this year when savings-and-loans in Ohio and Maryland ran into trouble and their so-called private insurers failed. But as policy analyst Catherine England recently pointed out, while the Ohio and Maryland insurers were private in name, they were not private in practice.

Those institutions, though privately owned, "were creatures of their state legislatures," England wrote in a study published by the Washington, D.C.–based Cato Institute. "The state legislatures established the rules under which they operated, defined acceptable and unacceptable activities for the institutions they insured, and basically made the state insurance funds subservient to the state banking commissioners."

In a Wall Street Journal oped piece, England contrasted the practices of the private FIAC with those of government deposit insurers, noting that while FIAC "exercises extensive oversight and disciplinary powers" over the institutions it insures, it simultaneously enjoys a flexibility of operation "that federal authorities, subject to political and legal constraints, cannot match." For example, FIAC charges different premiums, depending on an institution's soundness—whereas the federal insurance system charges the same rate to all institutions, whether they follow super-safe or highly risky banking practices.

Meanwhile, a proposal to introduce the prudent practice of variable rates into the federal system must go through the wringer of the political process. Even if it were enacted, England suggested in the Cato study, a federally imposed variable-rate premium would, for obvious reasons, be tailored to political purposes. "Indeed," England noted, government "risk-related premiums conceivably could be used to promote social goals," with certain groups given preferential treatment.

The Cato study advocated that the current government system of deposit insurance be replaced by private insurance. The competition and diversity of a true private insurance industry, the study contended, would create a much more dynamic banking system. To get there, analyst England suggested that private insurance be phased in through a "tiered" system: financial institutions would be able to buy insurance from both government and private insurers—100 percent from either type, or portions from both—and be freed of federal regulation to the degree that the institution has given up government insurance. "Forgoing its federal deposit guarantees," therefore, "would leave a bank totally deregulated."

The proposal is an elegant one, for it allows banks and savings-and-loans to individually decide how much government security to trade off for more freedom in the marketplace, while providing incentives for the growth of private deposit insurance. Policymakers should be lending their ears.

Let's Hear It for Tax Wars!

When the dust settles, the current round of tax reform may not reduce by much the overall federal burden on America's beleaguered taxpayers. But analysts are predicting that eliminating the deduction of state and local taxes could spur those governments to cut taxes and make corresponding cuts in the size of their governments.

In eliminating the deductibility of state and local taxes, the Reagan tax plan could send taxpayers in high-tax states running to their public officials and clamoring for tax relief—or send them running to lower-tax states. All this could lead to a new "tax war" among the states, predicts Business Week—"a battle over who can slash taxes most."

Politicians in high-tax states are terrified by the specter of hordes of overtaxed citizens demanding tax reductions or else. New York Gov. Mario Cuomo, for example, turned up in Washington to lobby against the measure. As Cuomo sees it, his state would be dumped between a rock and a hard place. Either taxes would be kept high and people would leave New York for lower-tax pastures, or taxes would be cut and the quality of life would decline because of concomitant cuts in government services.

But as Prof. E.S. Savas of the City University of New York recently pointed out in the Wall Street Journal, the governor needn't worry. State and local officials faced with diminished tax revenues have a proven alternative to letting garbage pile up in the streets: Privatize!

Evidence of the superiority of private over government provision of services such as trash collection and park maintenance "is now overwhelming and is no longer a matter of serious debate," opined Savas. He pointed to myriad studies—of subjects as disparate as street cleaning, prison operation, and city bus service—that have found that private companies can do it more cheaply and more efficiently than governments. For instance, a new study of 235 federal-agency contracts with the Office of Federal Procurement Policy shows that the cost of work done by government is 38 percent higher than contract work.

And with the elimination of state and local tax deductibility, privatization would have another count in its favor, notes Philip Fixler, the director of the Reason Foundation's Local Government Center, a privatization clearinghouse. Privatization often means turning to "user fees" instead of tax revenues to pay for services. But since state and local taxes—but not user fees—have been deductible, there is a bias in the system against user fees. Yet user-fee financing, Fixler told REASON, is a better route to privatization because it introduces prices and therefore incentives for efficiency.

So although "tax reform" is still "tax reform," this version may come with a modest silver lining. Citizens may succeed in cutting back on government at the local level and letting private individuals and firms show their stuff.

A Cold Bath Chases Away Protectionist Fever

A lot of politicians love protectionism. Foreigners make convenient (and nonvoting) scapegoats, and tariffs and quotas are nice ways to reward powerful industries and labor unions. But friends of free trade keep plugging away, and a trio of recent writings demonstrate just how cogent the case against protectionism is.

It may seem hard to believe that a nation's exporters would suffer from protectionism against imports, but it's true, say Kenneth Clements and Larry Sjaastad of the Trade Policy Research Centre in London, in a study called "How Protection Taxes Exporters." The Economist recently described their findings.

Imagine that a nation's steel industry has enough political clout to have tariffs imposed on steel manufactured by their foreign competitors. But the tariff has a ripple effect. Everyone who uses steel—like auto manufacturers—has to pay more for it; then consumers who buy cars have to pay extra at the auto dealer's; then consumers need higher wages so they can buy cars.

As The Economist notes, "the end result is higher inflation" in the country that has gone down the road to protectionism. And who is hit by inflation especially hard? Exporters. Why? Because inflation brings them (as well as other businesses) higher costs, and "they are the least able to recoup higher costs by charging higher prices," says the magazine. "They sell on world markets, and cannot raise prices there without being undercut by competitors."

All this is not idle theory. Clements and Sjaastad have compiled data from several countries indicating that exporters bear a big chunk of the burden of protectionism. Their portion of the burden exceeded 50 percent in Uruguay from 1966 to 1979 and in Chile from 1959 to 1970. It approached 70 percent in Australia from 1950 to 1980, and even exceeded 90 percent in Colombia from 1970 to 1978.

One of the most interesting parts of the study is a projection of what would happen to Australia's major exports if the government there imposed a 5 percent tariff on imports. As The Economist puts it, "The output of every export-biased industry falls with a thud." The five percent increase in tariffs would cause wages to rise by more than four percent, and export industries in turn would be 3.2 percent worse off. Thus, the study concludes that "more than 80% of the tariff increase [would be] converted into a tax on exports."

Protectionist myths took a further debunking in two recent Los Angeles Times opinion-page essays. Economist Robert J. Samuelson refuted the oft-stated canard that our manufacturing sector is disappearing (which is one of the key premises in the argument for protectionism).

Manufacturing employment, he noted, has fallen from 33.7 percent of nonfarm jobs in 1950 to 22.4 percent of nonfarm jobs in 1980. Yet manufacturing output in the United States has increased significantly over the last several years—it was 37 percent higher in 1979 than in 1969, and 7.2 percent higher in 1984 than in 1979. These figures suggest that, far from being moribund, our manufacturing industries are enjoying higher productivity.

Prof. Bernard K. Gordon of the University of New Hampshire likewise exposed several protectionist arguments as sham. First is the claim that America's exports are floundering in the world market. In fact, Gordon noted, the United States remains the world's largest exporter. The US share of the world market has not dropped below 12 percent in many years, and it has increased in the last year. And US-manufactured exports have fared even better, increasing their share of the world market from 17 percent to 20 percent in the last six years.

Gordon also took on the Japan-bashers. He pointed out that Japan bought $25 billion worth of goods and services from the United States last year, more than half of that in manufactured goods. And US exports to Japan are rising at a rate faster than the growth in Japan's economy.

Protectionist fever seems to break out in Washington every time an industry hits the skids. There is no known cure, but clear thinking of the kind displayed by Messrs. Clements, Sjaastad, Samuelson, and Gordon may yet provide an antidote.

More Reasons To Hail Taxi Deregulation

Once upon a time, there were about 420 taxicabs in Kansas City, Missouri. Now there are nearly 600. "Once upon a time" was last year, before the city deregulated its taxi industry by removing a limit on the number of cabs allowed to operate and by decontrolling fares. In those days there were only nine firms running cabs in the city—with one, Yellow Cab of Kansas City, Inc., dominating the market. But today more than 20 taxi companies are in the business, and Yellow's market share has dropped from 80 to 60 percent.

Craig Bates, president of Community Cab, Inc.—the city's second-largest cab company—told REASON that deregulation has spawned more innovation and a "wider diversity of services." The Kansas City deregulation, he suggested, is "the most successful deregulation experience in our industry's history." Bates, whose 1983 antitrust lawsuit against the city government (dismissed in early 1985) added to the pressure for deregulation, said that "there is no doubt that service has improved."

In fact, according to the city's taxi administrator, Judy Moore-Nichols, complaints over cab service have decreased since deregulation. And the Kansas City Times has reported that though the increased competition among cabs hasn't pushed rates down—at least not in the first year of deregulation—cabs have visibly improved their service to attract customers. "An upbeat strategy is emerging," the newspaper noted, "as companies jockey for profitability in a business that once was nearly given up for dead."

The experience of Kansas City, one of the more recent entrants in the trend toward taxi decontrol, offers yet more evidence to skeptics that cab deregulation doesn't result in chaos. In fact, the predictable increase in the city's available taxis suggests that urban chaos is thereby lessened somewhat—by maybe one or two fewer fights a day in the city dweller's continual travail of hailing a cab.

Milestones

? Workfare watch. California's conservative governor George Deukmejian and liberals within the state's legislature have agreed on proposed legislation to reform the state's welfare system. Under the proposed bill, all able-bodied welfare recipients, including mothers of children older than six, would be required to either work, take vocational training, or attend school. During the first six months of a limited workfare program initiated at the beginning of this year, California saved $1.2 million.

? Incomparable sense. "The wage gap cannot be closed by government intervention in the labor market." So declared Jeri Winger, president of the 500,000-member General Federation of Women's Clubs, in announcing the organization's opposition to the concept of "comparable worth." "An extensive imposition of subjective job-worth judgments would radically alter our present competitive market system," Winger noted, and "would force many small businesses out of business."

? Sorry, Norma Rae. Five Reagan Cabinet members have written each member of Congress warning that pending legislation to slap quotas on textile imports would impose a "very high cost" on American consumers. The legislation is cosponsored by a majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

? Dropping out. Struggle as they might to promulgate the public-school system, schoolteachers unions and blind egalitarians may be fighting a losing cause. The Department of Education's National Center for Education Statistics reported that enrollment in the nation's private schools is rising. In 1984, 12.6 percent of US school children attended private schools, up from 11.5 percent in 1980. Among private schools, nonsectarian ones had the largest increase in enrollment from 1980 to 1984: 36 percent.

Global Trends

From Marxism to Millionaires

HUNGARY—"If you hack in cabs or on computers, and if you have to work in a centrally-planned economy," says The Economist, "then almost everybody knows that Hungary is the place to be."

A series of reforms over the last 15 years has loosened the fetters on Hungarian entrepreneurs, who in turn have made this the most economically vital nation in the Warsaw Pact. The queues and chronic shortages endemic to Communist countries are comparatively rare in Hungary, whose bustling streets and thriving small shops stand in marked contrast to the commercial torpor of the Soviet Union.

The major reform that unleashed much of this energy was a 1982 act legalizing small private businesses. In the last three years, reports the Los Angeles Times, 320,000 Hungarians—6 percent of the labor force—have joined to form 23,000 "small ventures," ranging from car repair shops to hairdressing salons. And this is in addition to the 150,000 farmers and shopkeepers whose private activities were legal before the 1982 reform.

A shining example of the Hungarian entrepreneurial spirit is Zoltan Palmai, owner of Budapest's three-star Hotel Victoria, the only privately owned hotel in the Soviet Bloc. The gregarious Palmai, who dreams of becoming an Eastern European hotel magnate, labors under government regulations restricting him from employing more than nine people—comparable state-owned hotels have staffs three times as large—and 65 percent of his receipts are eaten up by taxation. Yet he pushes on, indefatigable, observing that "socialism doesn't have to be a social system of the poor."

Indeed it doesn't, at least in Hungary. The Los Angeles Times reports that Hungary may contain from 10,000 to 15,000 millionaires (the most notable is Erno Rubik, inventor of Rubik's Cube), a social blight that drives hard-line Marxists up the wall. Equally maddening to the Stalinists was a recent article in a government newspaper arguing that disparities in wealth are a necessary consequence of competition and efficiency and that all Hungarians will profit from the "acceptance of exceptionally high personal incomes."

There are limits to how much freedom Hungary's rulers will allow. Russian tanks, which quelled a popular uprising in 1956, remain ready to roll. But the spirit of enterprise is alive and well and on display in this remarkably resilient nation.

Flying toward Freer Flight

LUXEMBOURG—Internal pressure to deregulate the Common Market's airline industry continues to mount, with significant developments in the last few months. Over the summer, aviation chiefs of the 12 Common Market nations joined with those of 10 other European countries in issuing a policy statement calling for airline deregulation throughout the continent. The officials, who met under the auspices of the European Civil Aviation Conference, urged their national governments to ease both fare and route restrictions.

Soon thereafter, the European Court of Justice, the Common Market's top-level court, took on a case that may well end up deregulating the airline industry more quickly. The court will specifically decide whether the French government is violating the Treaty of Rome—to which Common Market nations are bound—in controlling the price of airline tickets sold in France.

The French government is prosecuting a travel agency for selling tickets below government-set limits. But the Treaty of Rome, the travel agency's attorneys claim, prohibits such price regulation in its stricture against barriers to the free movement of goods among the Common Market nations.

Among those who strongly support that interpretation of the treaty are the British and Dutch governments, which have been leading the move toward airline deregulation in Europe both in rhetoric and in practice. Dutch and British airlines enjoy the greatest freedom from regulation among the Common Market nations, and last year the two countries agreed to liberalize air service between the two nations—with noticeable benefits for the airlines and travelers.

Aviation Week recently reported that in the first year the two countries eased air-transport regulations between them, lower fares generated 70,000 additional passengers between London and Amsterdam. "At least 10 new services were started," the magazine noted, including six that "involve city pairs that had not previously received scheduled airline service."

Such results are encouraging the British and Dutch to further liberalize service between the two nations. And Britain and West Germany earlier this year agreed to a similar regulatory relaxation. Since the agreement, six new services between the countries have appeared.

These results provide strong evidence of the benefits of deregulation. They're not likely to escape the attention of the European Court of Justice in its deliberation over the French price-control case.

Global Roundup

? Bulgarian plot to feed the pope? Bulgarian rulers are allowing farmers more time to tend to their private plots—and the result is "a bumper crop," according to the New York Times. Though just 13 percent of the total land under cultivation is set aside for private use, these small private plots account for 27 percent of Bulgaria's total agricultural output.

? High finance. Only months ago the Himalayan kingdom of Nepal established the country's first stock exchange, and trading in the 11 listed stocks thus far is reported to be brisk. All the stocks are in government-owned companies that last year King Birendra started divesting by selling shares to the public, and much more divestiture is planned. The exchange is part of a deliberate plan to introduce capitalism into the developing nation of 16 million people.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Trends."

Show Comments (0)