A Dubious Debt Doubt

Do you believe, with many economists, that Uncle Sam will have to "inflate away" the ballooning national debt? Well, think again.

Economic policy in Washington today centers around the budget deficits and the mounting national debt. Politicians always want to spend—but nobody can propose any new spending programs until somebody figures out how to pay for all the old ones! There is no serious thought, however, of paying off the national debt nor even of stopping its growth, since that would mean actually balancing the budget. Starting to repay the debt would mean the federal government's annual budget would have to be in surplus—a quaint 19th-century notion to most people in Washington.

Most people believe the national debt or the annual budget deficit, which is the increase in the debt, are terrible economic things, monsters that cause all sorts of economic problems. The director of the Congressional Budget Office, Rudolph Penner, interviewed in U.S. News & World Report last August, was asked, "What will happen if nothing is done to reduce the debt?" He replied, "Eventually, there is little choice but to inflate the debt away. Obviously, if you have inflation, the outstanding debt is worth less in real terms."

This view that the debt must inevitably lead to inflation in the long run is widely held, but it is entirely wrong. Not only is there no connection in our modern economic system between government debt and inflation, but the very existence of deficits—the government's ongoing need to borrow—helps to prevent inflation!

How could this seemingly contrary conclusion be accurate? And how could well-regarded economists like Rudolph Penner claim that government fiscal policy in the long run would benefit by resorting to the printing press? The answers require a look at the nature of the government's debt today and the differences between our modern fiat money system and the classical version of paper money.

What makes the inflate-away-the-debt conclusion so apparently sensible is the fact that inflation depreciates the monetary unit, so that a nominal sum payable in the future (in this case, the government debt) becomes worth less in real terms. But it is also the case that the expectation of inflation drives up interest rates: If a return of inflation is possible, rather than being caught with their pants down, buyers of debt are motivated to get back as much as possible of their principal before inflation occurs.

The four years of gigantic deficits since 1981 have seen inflation fall from 13 percent to 3 percent. But while interest rates have also fallen—by 10 percentage points (from 20 percent in 1981 to 10 percent in 1985), they have not returned to the low historical levels that 3 percent inflation used to produce. The last time inflation was 3 percent, interest rates were 5 percent.

Obviously, many investors in the government's debt are worried by the possibility of inflation. But of all the reasons why we might see a return of inflation in the next 10 years—"irresponsible growth," a bailout of the banking system, gimmicks to weaken the foreign-exchange value of the dollar—the ballooning national debt and budget deficits are not part of that risk. For a return of inflation would have a perverse impact on the debt.

There is an implicit assumption behind the inflate-away argument that the national debt is like a single fixed-rate obligation, comparable to many home mortgages. The government debt, however, is quite diverse in its composition; it is composed mostly of short-term securities that are not vulnerable to inflation, so nothing could be gained by the government if it tried "to inflate away the debt."

The debt is more like a variable-rate mortgage than a fixed-rate debt. Rather than wiping it out, then, expectations of inflation—by propelling interest rates—tend to make the debt grow faster. This seems to be what is occurring today.

At the end of fiscal year 1984, the accumulated government debt of the United States was over $1.5 trillion. Interest on the debt during the fiscal year was $154 billion. The total deficit for the year—the annual increase in the debt—was $175 billion. If it had not been for interest on the debt, the deficit in 1984 would have been only $21 billion. It is clear that a high interest rate on the debt is a major cause of its rapid growth.

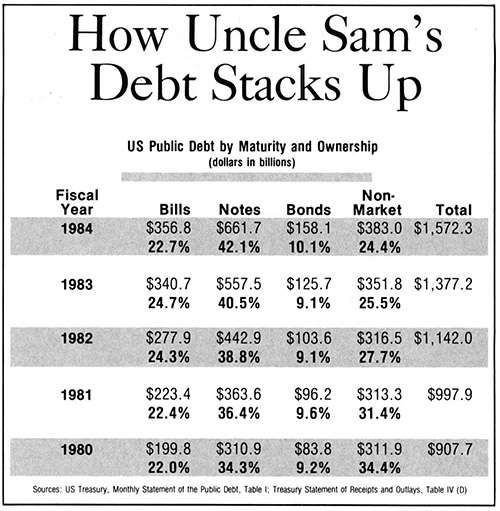

How much of the federal debt is vulnerable to inflation? The government debt comes in three "marketable" forms: Treasury bills, notes, and long-term bonds. There are also some nonmarketable varieties. Long-term Treasury bonds are issued for maturities of 10–30 years; Treasury notes are issued for 1–10 years; and T-bills are issued for less than a year, typically 90 and 180 days.

As the table shows, about $357 billion—nearly a quarter of the total debt in 1984—is in T-bills. This sum has to be rolled over in such a short period that the Treasury holds weekly auctions, and the buyers get the debt at a discount rate. The faster inflation moves, the deeper the T-bill discounts become. Clearly, the short-term debt is not vulnerable to inflation. To be vulnerable, the bond-holder has to be locked in.

As of October 1984, there was only $158 billion outstanding in the form of long-term Treasury bonds. These have a fixed interest rate and could be devalued in real terms by inflation, but they represent only about 10 percent of the total debt. Some of these will be maturing in the next few years, so the real exposure to inflation for investors who are locked in to long-term bonds is even less. There was about $662 billion in medium-term Treasury notes outstanding, but only $165 billion had more than five years to maturity—about another 10 percent of the total debt.

So the marketable obligations of the US government that even could be wiped out by inflation amount to only about one-fifth of the total. How could the debt be inflated away if only a fifth of it is vulnerable?

What about the nonmarketable debt? This was $383 billion, about a quarter of the total, and it could be wiped out by inflation. The long-term notes and bonds together with the nonmarketable debt are about 45 percent of the total. Yet the nonmarketable debt is owed by the general fund of the Treasury to other government trust funds, such as the highway trust fund and the Social Security system's trust fund.

The amount of debt that is truly "locked in" can't justify the conclusion that inflation is likely to solve the debt problem, because the government can't afford to wipe it out. What is the likelihood that some future government policy will deliberately "inflate away" the Social Security trust fund? The likelihood is zero! Social Security benefits are indexed for inflation and would increase at the same speed as the nonmarketable trust fund bonds, which are held to pay the benefits, were melting away. There is no way to get rid of the unfunded Social Security debts.

The very idea that inflating away the debt may be a policy option is so absurd that we can only conclude the economists, journalists, and stockbrokers who repeat such a notion haven't done their homework. They haven't looked at the facts or asked themselves how or why it might happen. Yet many intelligent people believe this clearly impossible theory.

Those who believe the government's ballooning debt might bring a new inflation are not just full of hot air, however. Inflation remains a very real threat today, and there has been a long tradition of governments inflating away debts! The father of modern economics, Adam Smith, in his famous book, The Wealth of Nations (1776), noted critically that no government had ever paid off its debt. After he died, the US government did actually pay off its Revolutionary War debt, but at about the same time several state governments defaulted on bonds. What is different today is the nature of a government's money.

The kings and governments that Adam Smith wrote about two centuries ago worked under a monetary system very different from the one we have today. When they borrowed money—or collected taxes—they received gold and silver coins. They seldom found it politically convenient to use the same coins to pay debts, however; it was easier to clip off part of the metal or to melt the coins and issue lighter, debased ones instead. The easiest way of all to repay creditors, of course, was to issue paper money.

But, while the classical monetary system was based on coins, the modern monetary system is purely bookkeeping entries and credit! Bank credit makes up two-thirds of the M1 money supply that is regularly reported in the news; the government's "bills of credit" circulate as paper money. And the coins are mere tokens of copper and nickel that have a metallic value much less than today's free-market price of the silver that coins of the same denominations used to have only 20 years ago. Modern central banks don't actually use printing presses to cause inflation. They expand credit.

When the monetary system is based on nothing but government credit, inflation is a loss of credit worthiness. Individuals rush to exchange their credit-money for tangible assets, houses, and land and refuse to lend money (that is, extend credit) to businesses except at interest rates high enough to hedge against the worst possible loss in real financial asset values. The real value of all the stocks traded on the New York Stock Exchange declined more in the period from 1970 to 1981 than in the depression period from 1929 to 1933.

Modern inflation is decapitalization. When a government can't borrow any more, it is helpless. The printing press is not useful when nobody will accept the money. If "inflating the debt away" were a policy option, we might ask why now, in the wake of the worst inflationary episode in America's modern history, the debt is larger than ever before!

The argument that governments eventually resort to inflation to solve their debt problems, because they simply cannot borrow any more and they can't possibly repay their debts anyway, presumes a special power of "sovereignty"—legal tender—that governments no longer really possess. They effectively abandoned it when they abandoned gold and silver coins. There is no longer any "real money" in the system for the governments to rip off. They have already taken it all out of circulation!

Modern governments are now wholly dependent upon the willingness of private parties to lend. This loss of sovereignty is quite obvious in the case of Latin American governments. Those governments have to carry debts denominated in currencies that they cannot themselves print: US dollars. Even the citizens of most Third World countries, and of many industrialized nations as well, keep their savings denominated in units of currency that their own government does not issue! In Israel and Argentina the people openly avoid using their government's money—much less buying bonds the government could "inflate away." In the United States it is not so obvious, but even here the degree of freedom-of-choice in money is wide.

Ironically for conservatives who agitate for a balanced federal budget, and perhaps even some repayment of the accumulated national debt, the achievement of that policy would take away a government's primary incentive to hold down its inflation rate—its dependence on a good credit rating. If the Treasury didn't have to sell T-bills every week, it wouldn't have to worry about the discount that its lenders demand as an inflation hedge. It wouldn't have to worry about its debt growing faster than the rate of real economic growth. The big spenders in Congress would no longer be silenced by the argument that budget deficits are our number-one problem. They would be free to rediscover all sorts of "national need."

A government with no current deficit, and therefore no further dependence upon creditors for new loans, would be a strong and independent sovereign. But that is not necessarily good if the government still has its pockets lined with old debts, incurred by a prior crew of big spenders. A strong government could, for example, insist that bondholders accept little green pieces of paper, which pay no interest, in exchange for large green certificates that pay 10 percent or more and eat up tax balances that the younger generation of politicians would certainly prefer to spend on new public works and subsidies.

There may be a terrible, new inflation in our future that could devastate our still basically free-market economy. But the ballooning national debt won't be the cause of it.

Contributing Editor Joe Cobb is an economist with the Joint Economic Committee of Congress.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "A Dubious Debt Doubt."

Show Comments (0)