Another Chance for Reaganomics?

A noted supply-sider diagnoses the problems with Reaganomics and writes a prescription for a second Reagan term.

Ronald Reagan came into office in 1980 with a set of economic ideas so seemingly foreign to the postwar consensus that his name was attached to it. "Reaganomics" promised to bring down inflation and unemployment and balance the government's books to boot. As a second Reagan administration looms on the horizon, it is useful to review the flow of economic policies in the first four years to see what went wrong in 1981–82 and what went right in 1983–84. History does not have to repeat itself.

There were always two sides to Reaganomics—a supply side and a demand side. The demand-siders were assigned the task of gradually slowing the growth rate of spending, or nominal GNP (gross national product), by slowing the growth of the money supply. This was the monetary program of Reaganomics. The supply-siders had the job of increasing the growth of production, real GNP, by reducing marginal tax rates and regulations. This was the fiscal program. I was briefly involved in both sides, as a member of Reagan's Inflation Task Force in 1980 and with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) transition team in early 1981.

This division of fiscal and monetary responsibilities quickly began to strain an uneasy truce between supply-siders and what can be called "the austerity school of demand management." On the monetary front, the supply-side prescription was countered by Beryl Sprinkel and other "monetarists," with their emphasis on the quantity of money. They repeatedly goaded the Federal Reserve to ignore falling commodity prices, the soaring dollar, and interest rates and stomp out even brief bulges in the money supply. On the fiscal front, conservative Keynesians—like Alan Greenspan, Charls Walker, and Herb Stein—successfully argued for diluting and postponing real reductions in personal tax rates.

But as supply-side economist Paul Craig Roberts had warned in a Wall Street Journal article in August 1980, "The promise of lower tax rates in the future would cause GNP and tax revenues to be lower in the present." In another Journal article on the eve of the recession, July 1981, I had added, "The dilution of [Reagan's] tax program jeopardized economic expansion."

Why was the issue of tax cuts so vital? President Carter's inflation had increased federal taxes from 18.2 percent of GNP in 1976 to 20.6 percent in 1980. His 1981 budget proposed to hike taxes further, to 23.6 percent of GNP by 1985—yet nonetheless expected real GNP to rise by 5 percent a year from 1982 to 1985.

It seems almost entirely forgotten by now, but when the Reagan team surveyed the economic problems they had been handed by the Carter administration, they were not optimistic about how quickly things could be turned around. The administration's 1981 "rosy scenario" actually forecast a recession in that year, a weak 5.2 percent recovery in 1982, and about 4 percent growth thereafter. These were remarkably modest objectives that required only two things, which did not happen—stick to the original schedule of cutting personal tax rates by 10 percent in both 1981 and 1982, and pursue a reasonably gradual tightening of the money supply.

There was a fork in the road, and taking the wrong turn made a great difference to the actual results. Had we stayed on the original path, the 1983 recovery surely would have occurred in 1982. And that projected 1982 recovery, in the OMB's estimation, would have produced a budget surplus in fiscal 1985. In other words, the failure to permit recovery in 1982 accounts for the entire estimated 1985 deficit, now pegged at $172 billion. (Separate studies by Robert Barro and Brian Horrigan similarly find that a deficit of around $160 billion can be completely explained as a hangover from inflation and below-normal real growth.)

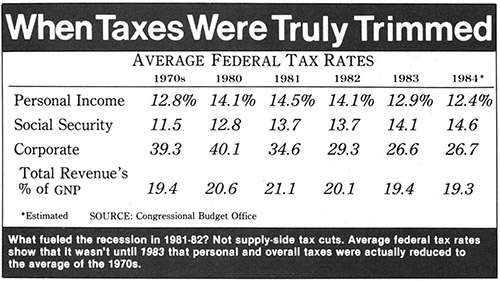

Federal tax rates were finally reduced, of course. To evaluate the impact, it is obviously essential to know when they were reduced. Officially, the first cut went into effect in late 1981. But as the table above shows, average tax rates increased in 1981. Even in 1982, personal tax rates (income plus Social Security) were still higher than in 1980—inflation had continued to push people into higher tax brackets, and the Social Security tax was increased. It was only in the calendar year beginning January 1983—also the start of the recovery—that personal and overall taxes were finally reduced to the 1970s average.

It is often claimed that the "Laffer Curve" can be laid to rest now. Didn't that symbol of supply-side economics say that if taxes were cut, people would work more and tax revenues would go up? Well, tax rates were cut, but the deficit has ballooned. But the Laffer Curve never promised that such a modest tax-rate cut as Reagan's would instantly raise taxable income enough to offset any revenue loss. The OMB and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) produce estimates of the revenues "lost" by the tax cut. But their static estimates are simply wrong—they still assume that much higher tax rates would have had no adverse effects.

Even the Urban Institute is complaining that federal spending rose "as a percentage of GNP" from 1980 to 1982. But that was not because President Reagan and David Stockman were big spenders; it was because private GNP fell in 1981–82. In the fourth quarter of 1980, the last under the Carter administration, federal spending was up 18.6 percent from a year before; by the fourth quarter of 1983, that annual increase had been trimmed to 3.2 percent.

In the first 10 months of fiscal 1984, tax revenues were rising at an 11.5 percent pace, while government spending was rising by 5.2 percent. Revenues that rise twice as fast as outlays will obviously narrow the budget gap if economic growth is permitted to continue. The complicating factor is that interest payments are up about 20 percent, courtesy of the Federal Reserve's hiking interest rates by 20 percent. Other federal spending is up only 2.5 percent, a decrease in real (after-inflation) terms, while real tax revenues are rising by 7–8 percent. In 1980, by contrast, real federal revenues fell by 1 percent while real noninterest outlays rose by 3.6 percent. Compared with Carter-Mondale "bracket creep," the Laffer Curve is doing very well.

Postponing effective tax cuts until 1983 was merely a disaster. The monetarist version of demand-side Reaganomics turned out to be much worse.

The monetarist goal laid out in the 1981 Agenda was to go for 7.5 percent annual growth of the "M1" money supply in 1981–82. The Fed came fairly close, delivering 6.9 percent. Despite later complaints about monthly wiggles in M1, administration monetarists really got what they asked for when they asked for it. Treasury Undersecretary Beryl Sprinkel publicly complained about supposedly excessive M1 growth on May 4, 1981, and January 22, 1982. The Fed responded by tightening the cost and availability of bank reserves at their meetings of May 18 and February 1. That kept the critical "fed funds" rate at 14–19 percent from May 1981 through July 1982 and correspondingly pushed up interest rates.

Proponents of postponed tax relief and what was, under the circumstances, excessively tight money argued that the combination would gradually slow the annual growth rate of nominal GNP to something like 10 percent. Instead, it abruptly squelched nominal GNP to a meager 2.8 percent rise between the third quarter of 1981 and the end of 1982, though M1 was rising at a 7.4 percent annual rate. This was not supposed to happen within the monetarist framework, but it did.

Jude Wanniski converted Herb Stein's 1976 phrase "supply-side fiscalism" into "supply-side economics" precisely to emphasize that supply-side is not concerned only with the effects of taxes but has a monetary side as well. But supply-siders within the Reagan administration were either disinterested in money or were deferring to the monetarists. Manuel Johnson at Treasury wrote in 1982: "Gold standard supply-siders see a major conflict between their views and those held by monetarists.…But this position falls outside the mainstream of economic thought and is not shared by supply-siders holding policy-making positions in the government."

One of them was Paul Craig Roberts, assistant Treasury secretary for economic policy. He sensed that something was going wrong, asking "Is a Depression Brewing?" in the Wall Street Journal in March 1982. But he still focused narrowly on the domestic money supply, oblivious to a rising world demand for US money. Roberts wondered "why the administration has closed ranks behind the Fed" and its tight-money policy, but he seemed unaware that his own support for Milton Friedman's monetarism had left the administration with no alternative.

People around the world really did believe that this administration would drive inflation down, and that belief made it safer to accumulate dollars. Indeed, the value of the dollar compared to other currencies had risen and commodity prices fallen from the moment of Reagan's election.

The Fed could not literally "control" the M1 money stock. All it could do was react to an observed spurt in currency and bank deposits by raising the interest rate on bank reserves. But this bouncing the fed funds rate up and down to chase M1 often made cash more attractive than bonds, and this created new risks for long-term investments because of sudden swings in bond prices. Paul Evans of Stanford University estimates that this instability alone raised long-term interest rates even more and reduced real GNP "by about 1 percent in 1980 and by about 2.5 percent in 1981 and 1982."

The supply-side criticism of 1982 Federal Reserve overkill is not mere hindsight. Jude Wanniski, writing in the New York Times in June 1981, warned of the burden of monetarism on the Reagan strategy. "Inflation is to be whipped with a world-wide going-out-of-business sale," he wrote. "Austerity is just around the corner for the GOP." The next month, economist Gene Birnbaum observed in the Wall Street Journal that a two-month bulge in M1 had prompted the Fed to raise "the fed funds rate back toward the 19%-plus area." Birnbaum rightly worried that "a combination of such exceptionally high real interest rates and a strong dollar…may ultimately crush the economy."

Likewise economist Robert Mundell, at an April 1981 conference in Italy, worried that "the United States will clamp down…in a squeeze that ends in widespread bankruptcy." He proposed to instead stabilize the dollar value of international gold reserves by easing Fed policy if the price of gold slipped below $400 and tightening around $450.

In June 1982, I surveyed the monetary wreckage in the Wall Street Journal: "A large and vital segment of the dollar economy, worldwide, is suffering severe deflation. Prices of industrial commodities have fallen every month since August, at nearly a 25% annual rate. Those who turn out primary products see their selling prices go down while interest rates stay up. That cost-price squeeze requires more borrowing to pay the bills, but the rising real burden of the debt leads to layoffs, plant closings and bankruptcies."

A month later, in the same Journal, monetarist Allan Meltzer showed that the faithful had not wavered. "If the Federal Reserve returns to high money growth, long-term interest rates will rise." But the Fed could no longer afford to listen to that paralyzing theory. Instead, finally ignoring M1, it began to meet the soaring global demand for dollars. And, contrary to the monetarist expectation, long-term interest rates fell like a stone.

The years 1981 and 1982 provided no test of either the tax or the monetary proposals of supply-side economists. Tax rates were not reduced in those years but were instead increased. Commodity prices and exchange rates were not stabilized but were instead destabilized.

What we experienced in 1981–82 was instead a massive failure of demand-side economics—a failure so glaring that the supply-side challenge became an unbearable embarrassment. Budget deficits were supposed to be inflationary, yet prices fell. The modest slowdown in the money supply was supposed to generate an equally modest slowdown in "aggregate demand," yet GNP collapsed.

The supply-siders, who had warned about all this from June '81 to June '82, were continually dismissed as too gloomy. In October 1982, when Polyconomics predicted that a normal 6–7 percent recovery would begin in the first quarter of 1983, the supply-siders were then dismissed as wildly optimistic. On January 4, 1984, in the Wall Street Journal editorial "Voodoo's Revenge," we made another controversial forecast of noninflationary 6.5 percent real growth—a forecast that finally became the "consensus" view seven months later. The demand-side fiscalists were again surprised, first expecting "crowding out" and stagflation by mid-1984, then adroitly explaining that it was the deficits that had, à la Keynes, "stimulated" the real economy.

Although the record was by this time clear on who had forecast what, supply-side adversaries were struggling to withhold credit and shift blame. Tom Redburn of The Los Angeles Times wrote at the beginning of 1984 that "until recently, supply-side boosters mostly had been licking their wounds, arguing among themselves over why the economic boom they had forecast had failed to materialize." Yet no supply-sider had forecast a "boom" from the tax increases and absurdly tight money of 1981–82. Supply-siders, in fact, were the only ones warning of the consequences.

Economist Morgan Reynolds of Texas A&M wrote that "the supply-siders' inattention to monetary theory has damaged their political influence, since their predictions have been falsified by events." Yet consider the predictions of that prominent monetarist Milton Friedman. In a letter to the Wall Street Journal in June 1982, Friedman worried that money growth was "dangerously high." Six weeks later, in his Newsweek column, the 1982 recovery that he had predicted had been "aborted by a drastic cut in money growth." In an October 25 interview with Barron's, that drastic cut had become an inflationary "monetary explosion." A year later, in September '83, Friedman wrote in the Wall Street Journal under the headline "Why a Surge of Inflation Is Likely Next Year." That was quickly followed by "A Recession Warning" in a Newsweek column in January '84. But within three months Friedman was back to telling the New York Times that "we shall be fortunate indeed if prices are not rising in the 7–10 percent range by the fourth quarter of the year." Professor Friedman's single-variable money-supply model was obviously unable to cope with the unfolding economy.

In 1983, both Keynesians and monetarists scrambled to take credit for a non-inflationary investment boom that they did not predict and that was based on policies they emphatically repudiated. Journalists began the amusing sport of blaming the recession on tax cuts and giving the Fed full credit for recovery. The Federal Reserve estimated that US industrial capacity was rising by less in the recovery than it had in the recession and then proceeded to worry that we were running out of capacity by producing so many machines. In a mid-1984 MacNeil-Lehrer debate with supply-sider Jack Kemp, Keynesian Charles Schultze saw "absolutely no evidence" that all this investment had added any capacity.

The demand-side economists tried to explain the US recovery with one or another of their single-variable models—the budget deficit or money supply. But if real growth really depended on the supply of government IOUs, then the recovery would have been sooner and stronger in other countries. Belgium and Italy, for example, had budget deficits of 12–14 percent of GNP, but Italy's economy stagnated while Belgium had modest growth. In the first quarter of 1983, when the US recovery began, the M1 money supply was up 9 percent from a year earlier, compared with 9.9 percent in West Germany and 17.5 percent in Switzerland, yet real GNP stagnated in Germany and Switzerland in 1983.

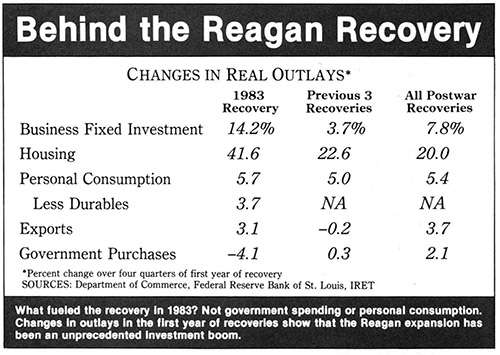

Keynesians shamelessly declared that this was their own, "consumer-led" recovery. In the New York Times in July 1984, Samuel Bowles claimed that "the big boost is from expanded…military spending." But the table below shows that the big boost was instead from business investment, housing, and consumer durables. Real government purchases actually fell, and true consumption (services and nondurables) was quite weak. Exports staged a good recovery, despite Third World poverty, and imports in 1983 were only 7.5 percent of GNP—down from 9.2 percent in the weak-dollar years of 1979–80. In the first half of 1984, business investment speeded up to a 20 percent rate of increase, and real GNP growth averaged a marvelous 8 percent between the second quarters of 1983 and 1984. Far from being an inflationary boom, as the monetarists predicted, or a Keynesian consumer boom, the Reagan expansion has been an investment boom of unprecedented proportions.

How could investment flourish despite abundant unused capacity in 1983 and the Federal Reserve's outspoken efforts to slow the progress with interest rates that were four times the rate of inflation? The only coherent answer is that the after-tax reward for investing was so attractive that it justified borrowing at such high real interest rates. Accelerated depreciation and the investment tax credit are obvious reasons, but lower marginal tax rates on "personal" income also raised the net return on unincorporated business and on individuals' dividends and capital gains. Clearly, reduced marginal tax rates on capital did induce more investment, and reduced tax rates on labor were favorable to both investment and employment.

Labor productivity, which had risen by 0.6 percent a year for nine years, now rose at a 3.3 percent annual rate from mid-1982 to mid-1984. And this was no Thatcherite trick of raising productivity by keeping output unchanged and firing workers. The combination of employment growth and productivity growth was without precedent. Wage gains remained surprisingly moderate, unit labor costs fell, and real wages rose.

As Leonard Silk of the New York Times has correctly reported, supply-side economics goes back to at least 1971, when Robert Mundell of Columbia University advocated reducing marginal tax rates to encourage added production, while stopping inflation by stabilizing the value of the dollar in terms of gold. This "Mundell mix" was offered as an alternative to President Ford's surcharge plan in Jude Wanniski's seminal article "It's Time to Cut Taxes" in the Wall Street Journal of December 11, 1974.

Wanniski reported that Mundell "would adjust income tax brackets across the board and index them.…If taxes are not cut now, the size of the unemployed sub-economy will expand. Tax revenues of state, local and federal governments will decline. At the same time their outlays for unemployment relief and welfare will expand. Combined government deficits might even exceed the amount implied by a tax cut.…With lower taxes, it is more attractive to invest and more attractive to work; demand is increased but so is supply."

"The dollar would appreciate against foreign currencies," Wanniski continued; and "dollar holders will have a higher incentive to invest in capital goods.…Capital that is now flowing out will remain; foreign capital going elsewhere would come in. The increased real economic growth would mean the U.S. would run a sizable trade deficit.…The expectation of slower inflation would cause a reduction in optimal inventory levels." Nine years before his policies were tried, Mundell had accurately predicted their effects.

Those who were surprised by the outcome of Mundell's advice have attempted to deny that the US economy in 1983–84 has, in fact, performed better than it had in decades. For example, in the New York Times in January 1984, socialist Michael Harrington wrote: "The Reagan supply-side strategy failed: Production did not turn upward, because the rich and the corporations did not invest the enormous tax subsidies."

An equal reduction in tax rates is considered "unfair," in this view, because low-income individuals who pay no taxes receive no direct benefit from a tax cut. What was actually unfair was that the 50-percent maximum tax has not yet been reduced at all. The top 1 percent of all taxpayers paid 7.5 percent of all the income taxes collected in 1978, 8.5 percent in 1980, and 9 percent in 1982. The recession did, of course, cause a certain amount of poverty; but a study by Richard Nathan of Princeton found that the 1981 budget cuts had "much less of an impact on [government] services than people believed."

Supply-siders have grown accustomed to being criticized for positions they never held and predictions they never made. Economist Barry Bosworth recently managed to write a whole book about supply-side economics without quoting a single supply-sider, offering only a footnote for one supply-side fiscalist (Norman Ture, who joined the Treasury Department in 1981).

Bosworth leans rather heavily on an old fallacy, claiming that the "income effect" of tax cuts could be a disincentive to produce. That is, people will be so much wealthier because of a tax cut that they may work and invest less than before. Of course, if everyone produces less they will soon be poorer, not richer; and being poorer, on Bosworth's theory, should make them work harder. Poverty is what creates wealth in the Bosworth model. Yet the theory of tax incentives is not really ambiguous or paradoxical, as has been rigorously explained by James Gwartney and other supply-siders whom Bosworth chooses to ignore.

It is particularly ironic that supply-side is so often judged, by Bosworth and others, according to the so-called personal savings rate. The savings rate is the Keynesian "marginal propensity to save," relabeled as supply-side by such zero-sum theorists as Martin Feldstein and Lester Thurow. "Real supply-side economics," claimed Thurow in the Chicago Tribune in May 1983, "would require Americans to endure a 5-to-10 year period during which consumption and the standard of living must fall in order to make room for investment."

In genuine supply-side analysis, people produce in order to consume or to acquire assets that will let them consume later. A tax system should not be biased against either present or future consumption, since both are incentives to produce. By improving incentives and dynamic efficiency in the economy, supply-side economics intends to raise the quantity and quality of goods and services over time, or "potential GNP." In that case, both savings and consumption would rise.

The "personal savings rate," or percentage of current personal income that is not consumed, would be a particularly perverse supply-side target. It could probably be raised, for example, by reducing personal income with a big tax increase. In the taxflation of 1974, the savings rate soared to 8.5 percent, as income and wealth contracted; yet the real value of current and past savings nonetheless fell.

Within these Keynesian accounting categories, however, even personal savings are understated because purchases of consumer durables are considered consumption instead of saving, and government employees' payments for life insurance and retirement funds are tallied as taxes instead of saving. These are more appropriately accounted for in the Federal Reserve's flow-of-funds measurement of "personal" savings, which showed the savings rate to be 11.1 percent in the first quarter of 1984 (versus 6.1 percent as calculated by the Commerce Department).

Savings is an increase in wealth, and the booming stock and bond markets of 1982–83 raised real wealth by at least a trillion dollars. Paper claims against future production became more valuable with expanded opportunities for profitable production. The enormous increase in reinvested corporate profits should also be considered "personal" savings—people own the corporations. Combined corporate and personal savings (even without the Federal Reserve adjustments) rose by 22 percent in the first five quarters of the recovery, going from 16.9 to 18.1 percent of GNP. At the same time, combined government deficits fell from 33 to 17 percent of private savings.

Criticism of supply-side policies from conservative and libertarian scholars does not recognize that the supply-side economic expansion has also contributed to their own agenda—negligible inflation and reduced growth of government spending. Murray Rothbard would have people believe that "supply-siders care not at all for the deficit or for the level of government spending." Thomas Hazlett wrote in 1982 that "the Soviet Union is the quintessential supply-side economy," and "implicit in all supply-side prescriptions is a positive view of government spending." Leland Yeager in 1984 decries "today's tacit alliance between big spenders and supply-side inflationists." "We who are more libertarian," he suggests, should "ponder the idea of strictly temporary tax increases." He accuses supply-siders of having "caricatured monetarism unfairly," although he wrote in 1983 that "Reynolds is right in asking us to look beyond monetarist prescriptions."

Supply-side advocates of a commodity standard or stable exchange rates are not "inflationists" because they complain about falling commodity prices or an ever-rising dollar. We would be inflationists only if we did not also advocate monetary tightening whenever the dollar collapsed and the price of gold soared.

Yeager believes it is "grossly irresponsible" for supply-siders to question the mismeasurement of deficits or to ask for evidence that deficits necessarily raise either interest rates or inflation. The burden of proof, however, is on the other side. An exhaustive survey of two dozen studies trying to link budget deficits and interest rates, in the CBO's February 1984 Economic Outlook, found no credible evidence of any significant effect. It is not that deficits "don't matter" but that deficits of the magnitude recently experienced are less damaging than trying to squeeze equivalent tax revenues out of one year's output.

Any ill-effects from government (or private) borrowing depend on the methods of finance and the specific alternatives being proposed. Government spending is the average burden of government, but the marginal burden on new production depends on specific timing and methods of taxation. The reason for cutting federal spending is also the reason for cutting marginal tax rates—both changes free up resources for uses that people acting in the market prefer, and both improve incentives for production and exchange. A deficit does imply that tax revenues must be higher in the future to service the added debt, but a larger economy can generate that added revenue at lower tax rates.

The solution to deficits offered by Walter Mondale is simply a replay of 1978–80, with a similar cast of advisors. He wants to repeal tax indexing and sink the dollar's value by 30 percent, so that working couples can be inflated into higher tax brackets. This Mondale "policy mix," advocated by Barry Bosworth and others, is the exact opposite of the "Mundell mix" of stable money and low marginal tax rates. The effects are also the exact opposite—Mondale's proposals would ensure chronic stagflation.

The supply-side of Reaganomics has been so successful in revitalizing the economy that the demand-siders have repeatedly urged higher tax rates and higher interest rates to slow the allegedly "overheated" recovery. It must always be remembered that such advice comes from the same economists who were responsible for the policies of 1968–82. Monetarism, in particular, is the main casualty of 1981–82 and must be fundamentally reconsidered.

The experience of 1983–84 shows what invigorated enterprise can accomplish with modest encouragement. A second Reagan administration should press forward with lower marginal tax rates on a broad and growing tax base, further liberalization of trade and regulations, and a long-term guarantee of the dollar's value in gold. Of course, the trial-and-error process of economic policy in the first term was based on a conflict of ideas, and some of that controversy will continue into a second. But if it is to succeed in maintaining vigorous economic growth without inflation and without budget deficits by 1989, the administration will have to grope its way back to the original path—the fork in the road not taken in 1981.

Contributing Editor Alan Reynolds is chief economist at the economic consulting firm Polyconomics. He first published in REASON in July 1971 ("The Purge of Chicago Economists").

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Another Chance for Reaganomics?."

Hide Comments (0)

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mute this user?

Ban this user?

Un-ban this user?

Nuke this user?

Un-nuke this user?

Flag this comment?

Un-flag this comment?