Feet to the Fire

What happens when a private fire company fails to satisfy its customers?

In 1976, the rural area surrounding the small town of Grants Pass, Oregon, had one of the few privately owned and operated fire departments in the nation. And Grants Pass Rural Fire Department had been serving the area for 19 years.

But this private fire department wasn't doing very well. Prompted by citizens' complaints about rural fire service, county officials had set up a Fire Protection Study Committee to evaluate the five fire services operating in Josephine County in southwestern Oregon. The committee's report, completed in September 1976, concluded that the county's recent track record in fire protection was "extremely poor." And it was clear that the culprit was Grants Pass Rural, the only private fire service among the five.

The committee reported that for the five preceding years, the county's ratio of fire loss to the value of property involved in fires was 30 percent—compared to a statewide average of less than 4 percent. Other data pointed to the reason for the high loss ratio in the county: poor protection by Grants Pass Rural. In its service area, the property loss was averaging $13,596 per fire in insured structures. In the area served by the town fire department in Grants Pass, in contrast, the average loss was running only $2,052; and in another rural area in the county it was $3,986.

"We are in trouble!" concluded the study committee. "We need better fire protection!" It is not surprising that the options for improvement presented by the committee were all variants of establishing government-operated, tax-supported fire services throughout the area. Of course, 8 of the 14 committee members and all 5 advisors to the committee were government officials. But the fact is that government provision of fire protection is nearly universal in the United States and in this case had an excellent record compared to private Grants Pass Rural. Shutting down Grants Pass Rural seemed to be the only solution.

The 1976 study was presented to the county commissioners, where it languished without action for two years. Complaining, Chief Gerry Ryan of the Grants Pass (city) Fire Department and a member of the study committee told me in 1982: "It was taken to the county commissioners and it died. It was never given to the public for a vote." But in October 1978 the county commissioners cranked up another effort and appointed another committee.

Neither the commissioners nor the new committee members nor local citizens were prepared for what was to come. As the committee gathered for its first meeting, in drove a brand-new, shiny yellow fire truck with "Valley Fire" emblazoned on its door. "The media were obviously very curious as to what was going on," recalled Phil Turnbull, whose idea it was to set up a second, competing private fire department instead of replacing Grants Pass Rural with a government service. Turnbull proceeded to announce that Valley Fire Service was going into business in the area regardless of what the committee did.

The young entrepreneur's plans had been well laid. "I am a believer in free enterprise," Turnbull explained in an interview. "But it was no love of free enterprise that got me started. It was just disgust with the situation." Living in the Grants Pass area, and a fire fighter by profession, he was well aware of the woefully inadequate fire services in the rural area and wanted to do something about them.

Turnbull's first move was to join forces with a partner, with his father, and with his brother. Together, they commissioned a feasibility study by researchers from nearby Southern Oregon State College. The researchers were to explore the idea of bringing another private company into the area.

The feasibility study turned out to be so favorable to the idea that they were able to raise an initial investment of approximately $100,000 through the sale of stock. It took Turnbull about a year to raise the money, working on his days off from the Eugene department. "As the new trucks came up for delivery, we managed to get another $10,000 to make the down payment," said Turnbull. "It was a struggle."

When the county's new study committee was formed in October 1978, Turnbull said he was worried "because the one in '76 had come pretty close to abolishing free enterprise." So they decided to make their debut at the committee's first meeting. Valley Fire Service had been incorporated in the state of Oregon in August. "We were selling stock, and we were moving," said Turnbull. "But we had not gone public yet. Nobody knew we were coming at all."

Shortly after he showed up for the meeting in the first tanker the new firm had bought, the county's study committee disbanded. In June 1979, Valley Fire Service opened for business. Grants Pass Rural, which looked to be in eminent danger of being forced out of business in 1976, continues to operate. So now rural Grants Pass is the only place in the nation with competing, privately owned and operated fire departments.

But how are the residents faring with private firms providing an "essential service" that is traditionally run by the government? Private enterprise seemed to have failed them in 1976; is it now a good solution to their need for fire protection? That's what I wanted to investigate after learning how competition came to rural Grants Pass.

There are many similarities between the two private fire departments in Josephine County—Valley Fire Service, with Phil Turnbull at the helm, and Grants Pass Rural, headed up by Bertha Miller.

Both, of course, are privately owned companies that charge a yearly fee to customers who subscribe to their respective services. Both offer protection against fires and emergency medical service. Grants Pass Rural also operates a conventional ambulance service, one of three in the area.

Although both firms seek paid subscribers for their services, both will put out nonsubscribers' fires and then try to collect an expensive fee later. The charge is $150 per fire engine per hour and $10 per fire fighter per hour. But these charges are not always easy to collect, according to Bertha Miller of Grants Pass Rural. She told me that the collection rate for nonsubscribers "has been very low over the years. We have had attorneys say to people, 'You don't have to pay them.'"

In addition to performing the traditional fire department services, both firms will even come and rescue your cat from a tree. They see that service as good public relations, and both have favorite cat stories, dog stories, and even skunk stories.

Both Miller and Turnbull intensely dislike the idea of government regulations, but amazingly, they don't encounter many. Turnbull said he didn't have to ask permission from any local government body to establish his business. This turns out to be a very important fact.

Both private fire services are almost in awe of the Insurance Services Office. The ISO is a nationwide nonprofit private insurance service that rates the quality of local fire protection for the benefit of companies that write fire insurance policies. Based on criteria such as the water supply in the area, distance from a fire station, and the number of available firefighting units, the rating system assigns numbers from class 1 through class 10, with the lower numbers reflecting the better fire services. Most rural fire districts, whether government or private, are rated between 8 and 10. A class 10 rating implies virtually no available fire protection; a 9, rudimentary service; and an 8, adequate rural protection. Ratings of 3 to 5 are more typical of suburbs and cities. The lower the ISO rating, the less money local residents have to pay for fire insurance.

Both Valley and Rural hate criticism, especially when they feel it is underhanded. I had to ask both Miller and Turnbull about an Associated Press news story that portrayed the two private fire services as Keystone Kops-style fire fighters who, according to the headline, "Battle Blazes—Sometimes Each Other!" The story went on to paint a picture of the two services racing around the county fighting each other over fires.

Have they done that? "No!" shouted Mrs. Miller. "We have never fought at a fire that I know of. That just makes me furious." Turnbull called the story "absolutely ridiculous!" He insists, as does Miller, that the two firms have a good working relationship.

In spite of all the similarities between the two fire services, though, they are much more different than alike.

Phil Turnbull, 26, is a sandy-haired man of medium height. He met me in a crisply starched uniform and offered immediately to show me Valley Fire's facilities. The station to which he took me was a brand-new building, clean and well cared for. Everywhere, the employees seemed to exude pride, efficiency, and enthusiasm.

But the example for all those virtues is Phil Turnbull himself. In business for a little short of four years, he has already established his fire service on a sound financial footing. In 1982 the company took in just under $400,000 in gross revenues, and it now has about 5,400 subscribers to its services. Valley Fire is owned by stockholders, 16 of whom are employees, and is run by a five-person board of directors where Turnbull serves as secretary in addition to working for the firm as fire chief.

Currently, Valley Fire operates three stations and plans to build a fourth soon. The company has six operating vehicles and is rebuilding four others. The number of employees fluctuates between 40 and 45. Nine of these are full-time employees. The rest are reservists who are paid only when they work, and then they are paid the minimum wage rate.

Even though Turnbull's people are employees of a private company, Valley Fire Service is organized in a paramilitary manner, just like other fire departments. There are ranks like captain and lieutenant, and everyone is expected to follow orders. Turnbull explained why: "You can't get away from the fact that you have an emergency service here. We put that above even the financial end—profits or any of that stuff. You can't mess around with quality of service. When you get to the scene, you have got to act in a professional manner."

Although Valley Fire's training program is not itself accredited or recognized by the state, many of its employees have achieved or are working toward state certification. In addition, recruits must complete a six-week training program at Valley Fire before joining the reserve ranks. And continuous training is required for full-time employees (two hours a day) and reservists (a weekly drill).

Compared with ordinary fire departments with a civil service structure, private fire services have the advantage of being able to dismiss employees easily. "I have had other fire chiefs tell me that they envy the fact that I can fire employees," said Turnbull. "I have and I will."

Valley Fire charges subscribers $2.15 per $1,000 of the market value of the structures on a subscriber's property if the subscriber lives within five road miles of one of its fire stations. (Those areas are rated class 8 by the Insurance Services Offices.) If a subscriber lives more than five miles from a station (rated class 9 by the ISO), the fee is lower, $1.15, in view of the longer response time involved and the lower probability of saving the structure.

Of course, nobody is forced to subscribe. But most people find it economically advantageous to do so. Valley Fire sales literature in 1981 gave the example of a house worth $70,000. If the homeowner did not subscribe to a fire service, the annual fire insurance premium would be $499. But in the Class 8 areas, having a Valley Fire subscription would slash the premium to $238. The cost of the subscription was $107, for a total outlay of $345—a net saving of $154 a year compared with not subscribing. Even in the Class 9 areas, where the insurance premium remains fairly high, there would still be a $31-a-year net saving.

Valley Fire offers some important customer services that are not usually provided by government-operated departments. When signing a contract that states what the company will do in return for its fee, subscribers are asked to specify structures to receive priority protection, any water sources on the property, the number of occupants in the houses, the number of invalids, and any obstacles to approaching the property, such as bridges or gates. This information becomes part of the contract with the company.

As with most other businesses, Valley Fire has to advertise to obtain customers. When the company first started, the main requirement was to let people know of its existence and to explain how its service differed from that of Grants Pass Rural. (The initial emphasis was on greater savings through lower insurance rates, since Grants Pass Rural could not offer Class 8 service until 1982.)

Business manager John Mustard, a former newspaperman, hit upon the idea of publishing a tabloid newspaper as a marketing tool. Thus, twice in 1981 residents of the Grants Pass area received a free "shopper"-style newspaper, with articles about Valley Fire and about fire protection and fire safety in general. The tabloid was actually self-supporting via advertising, just like conventional shoppers. After two issues, the company had achieved significant name recognition and market penetration, signing up about 50 percent of all households in the area. Mustard shifted the marketing effort to newspaper ads, a small amount of radio advertising, and direct mail. In 1982, door-to-door sales representatives were added.

I asked Turnbull what kind of vision he has of Valley Fire's future. "We have put every penny we have made back into service improvements," he said. "Our commitment to the community is not superficial. We have been making some very long-term, heavy-duty investments into equipment and into improving the quality of service. The board of directors is very adamant on keeping the quality of Valley Fire Service up. One of the reasons for that is a downright selfish reason—we think there is room for expansion out there into other areas." Turnbull predicted that the stockholders will probably be paid their first dividend this year.

People who view fire fighting traditionally, as a "public service," may be uneasy with the idea of fire fighting for profit. But the profit motive is a positive factor in Turnbull's opinion: "I do know way in the back of my mind that I am constantly wanting to work as well as possible, perform as good as possible, be as good as possible. And I think that incentive is definitely there because of the profit motivation. It inspires efficiency and productivity."

But over at Grants Pass Rural Fire Department, Bertha Miller has a different opinion. "I don't think you can talk in terms of profit in this fire department," she told me. "I think it has always more or less been based on service for humanitarian purposes. We haven't been too concerned with profit."

Bertha Miller is a middle-aged woman who met me in a food-stained t-shirt and ushered me into her office in her home, where a man lay sprawled on the floor fast-asleep, a baby was squalling, and a huge green parrot was jabbering in the background. She refused to show me any of Grants Pass Rural's stations or fire equipment.

Yet Mrs. Miller is undoubtedly one of the pioneers of private fire services, not just in Grants Pass but also in the nation. She has been associated with Grants Pass Rural for 25 years and has been running it for 12.

Mrs. Miller and her husband Walter took over in January 1958 after the original owner had run the department for less than a year. Ever since 1958 there have been problems, she said, and she talked about those problems a lot: "When we started out, there was an awful lot of politics involved, practically from day one. There have been a lot of hardships."

One of those problems was that in 1970 her husband left town. "He left five kids and myself and a business that was heavily in debt." I was surprised when she commented that she had no firefighting experience when she took over the direction of the fire department. The only experience she could point to was "a lot of reading, some research, and I saw some films."

At present, Bertha Miller isn't the official owner of Grants Pass Rural. Officially, it is owned by members of her family. The reason for that directs attention to one of her long-standing problems: she has had a lot of trouble with the Internal Revenue Service.

Ever since 1969, the IRS has placed numerous liens on the company's property and equipment because of unpaid personal income and employee payroll taxes reported to be as high as $150,000. In May 1981 the IRS confiscated 28.5 acres of the company's property and then sold it at an auction to pay back taxes. A few months later the IRS was back to confiscate the company's firefighting vehicles. Mrs. Miller made an emergency appeal for funds from her loyal customers and raised enough money to get the vehicles back. According to Mrs. Miller, an IRS agent told her, "You will give your business to your son or daughter or I will close it out right now."

After Mrs. Miller had her troubles with the IRS, some of the local media implied that her company was about to fold. "I think next July it will be four Julys that we were 'going out of business,'" she exclaimed. But she insisted, "We never were out of business."

And that business, she claimed, amounts to six stations and "about a dozen vehicles," although she would not give me a grand tour. The service is currently run, she said, by "nothing but volunteers." Customers pay $40 a year, which includes not only fire protection and emergency medical service, but ambulance service.

Aside from the IRS, however, it is clear that Mrs: Miller's biggest problem to date has been the evaluation her company received from the 1976 Josephine County Fire Protection Study Committee Report. This study did not present a flattering image of Grants Pass Rural. Specific items in that report included:

Criticism of the quality of Grants Pass Rural's equipment. At its Sunny Valley substation, the "station" was described as a tree located on a KOA campground under which the station's 1950-ish vehicle was parked. A local fireman told the committee investigators that the vehicle had a bad battery, and "sometimes the truck had to be pushed down the hill to start it."

At the Merlin substation, the study reported, "There was no vehicle in the building and no tire marks to indicate recent entry or exit." For this substation, the study concluded that "it is reasonable to assume that the Grants Pass Rural Fire Department Substation at Merlin exists in name only."

At the company's main station, the investigators found 15 vehicles but reported: "It is obvious that all of this equipment is not operational." Overall, of six alleged substations, one did not exist at all and only three of the others had buildings (the other three, like Sunny Valley, consisting merely of a parked truck).

In addition, at most of the Rural stations they found no breathing equipment, no asbestos suits, few alarms and little communications equipment (most of the fire fighters were alerted by telephone, not radio!), and no heating to keep the vehicles' water from freezing in winter. And the majority of the vehicles, they noted, were built in the early 1950s.

The report was also critical of Rural's response time in arriving at the scene of fires. Some of the customers lived so far away from a station that any response "would require a minimum of 15 minutes to cross the bridge and proceed through Grants Pass and then into the county."

The study noted that Grants Pass Rural had a poor record for saving property. Figures from the Oregon State Fire Marshal showed that for the 7 years preceding 1976, the property loss per structure had averaged $13,596 for the 296 insured structural fires fought by Grants Pass Rural. By comparison, during the 10 years preceding the study, the average loss for the Grants Pass (city) Fire Department was only $2,062 per structure. Compact urban areas can be expected to have better-quality fire protection than spread-out rural areas. So a better comparison is with a rural fire district: Over the same 10 years, the average loss for the rural, government-run Illinois Valley Fire Department in the county was $3,986 per structure. So Rural's average fire loss was nearly three and a half times higher than that of a comparable rural fire department.

One might expect the 1976 study to have been somewhat biased, since it was prepared and backed by people who seemed obviously to be leaning toward the abolition of private fire service in rural Grants Pass and the establishment of a tax-supported, government-operated fire district. But there is other evidence to corroborate the study's findings.

Part of the 1978 feasibility study commissioned by Phil Turnbull and his associates contained a questionnaire to be completed by residents in the Grants Pass Rural service area. It turned out that 88 percent of the residents in the area said they would be willing to consider contracting with a new company. Nearly 45 percent of the respondents rated fire department service in the area as "below average" or "poor."

I talked to some customers in the area in 1982 and found both defenders and critics of Bertha Miller's Grants Pass Rural. But one of the detractors made a telling remark: "A lot of people call them the foundation savers. Their equipment was a little older, and they always had problems with it." This customer had had his contract with Grants Pass Rural, but he switched to Valley Fire and was grateful to have the opportunity to do so.

In all my interviews with Bertha Miller, she never mentioned better service as a solution to her problems. Nor did she talk about any efforts toward improvement following the 1976 study. Instead, she seemed primarily concerned with absolving herself and her company from responsibility for Rural's problems. These she blamed variously on the IRS, on bad press reports, on the "politics" of the 1976 study, and on competition from Valley Fire Service.

Referring to her competitors, Mrs. Miller has already told the local media: "They're out to get me, and there's no two ways about that." She confided to me her belief that Valley Fire is foolish to have entered the market with the idea of making money: "I can't understand why people come into this town and think they can get rich."

Comparing the two private fire services is not easy. But even harder is comparing them with government fire services in the area. All such comparisons are inherently difficult: no two service areas are exactly alike, and fires are relatively infrequent, randomly occurring events. One large fire in a particular year, which could happen anywhere, can significantly alter that year's fire-loss statistics. Nevertheless, it is possible to make some general comparisons.

One useful measure is the "loss ratio"—the ratio of the amount of value lost to the total insured value of the properties involved in fires. The lower the loss ratio, the more effective the fire department in saving structures. In Oregon these figures are compiled each year by the state fire marshal from data furnished by insurance adjusters. For 1980, the latest year available, the statewide average loss ratio was 8.5 percent. By contrast, Valley Fire's loss ratio was only 3.3 percent. Grants Pass Rural, on the other hand, had a 1980 loss ratio of 40.2 percent (and an average of 21.5 percent over the five years 1976–80).

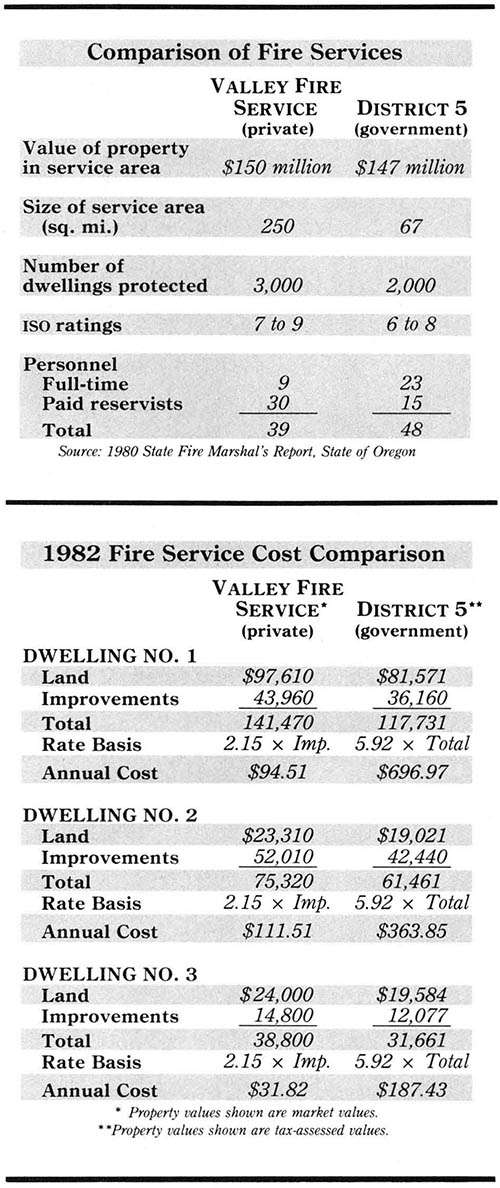

How does Valley Fire compare with nearby government fire services? It would be invalid to compare a basically rural service with the more urban service provided in towns like Grants Pass itself. A more reasonable comparison is with a (tax-supported) rural fire district, such as Jackson County District 5 in the nearby town of Phoenix, Oregon. As the table on this page shows, although Valley Fire's service area is much larger, it protects an equivalent amount of property value. As can also be seen, the government fire district has more fire fighters and a somewhat better ISO rating. Officials of both Valley Fire and District 5 agreed that in terms of land use, population density, and structural characteristics, the two areas are roughly comparable.

So how does fire service in these two areas compare? District 5's 1980 loss ratio was 41.7 percent—compared to Valley Fire's 3.3 percent. District 5's average over the five years 1976–80 was 25.5 percent. Clearly, the quality of the fire protection provided by tax-funded District 5 is much lower than what Valley Fire has been accomplishing in its first several years of existence.

What about the cost of service? Valley Fire charges $2.15 per $1,000 of the market value of structures on a property. District 5's tax rate is $5.92 per $1,000 of assessed value of the total property (land and structures). To provide a basis for comparison, I asked John Mustard, Valley Fire's business manager, to select three typical residential properties in the area, ranging from low to high in value. I then calculated the annual cost of fire service if the property were to be served by Valley Fire or by District 5. As the table below makes clear, the government fire service costs between 3.25 and 7.4 times as much as the private fire service! And this is for service whose quality is decidedly worse.

So what do the chiefs of the local fire departments think of the two private fire departments in Josephine County? The two chiefs I interviewed do not approve. But, ironically, they seemed to disapprove of Valley Fire more than they disapproved of Grants Pass Rural, despite the former's clearly superior performance.

"I have a much better working relationship with Rural than I do with Valley," said Gerry Ryan, chief of the Grants Pass (city) Fire Department. "Valley has come in and they have nice new equipment," he continued. "I don't know personally if they are any better than Rural." Yet Gerry Ryan was one of the members of the county's study committee that produced the 1976 study condemning Rural.

Chief Ryan had many criticisms of the very idea of private fire departments, but he said a big concern with the local private services is their lack of manpower: "You have got to have more than one man or two men on duty. It takes equipment to put out a fire. They rely on volunteers." Valley Fire keeps an average of two people on duty at its stations in late-night hours, but Ryan objected: "The most important thing in fighting a fire is the response you have on arrival at the scene. A two-man fire department just will not do it."

What Chief Ryan disparages as "volunteers," however, are actually paid reservists—fire fighters with some training who normally work at other jobs but are on call to respond to fires. All fire departments in the area—Ryan's included—use a mix of full-time and on-call personnel. In some of the smaller districts these people are, in fact, volunteers. But most are paid at least token amounts. And Valley Fire, because it's a private enterprise, must pay its reservists at least the minimum wage. Unfortunately, the Oregon State Fire Marshal's report perpetuates the confusion by lumping all on-call fire fighters into the single category of "volunteers."

Because Chief Ryan seemed concerned about it, I asked him whether he thinks private fire services might be willing to sacrifice service to make a profit. "With Valley I would say yes," he replied, "because they are only going to have two men at the station to put out a fire. They don't have the manpower to do it. To make a profit, they have to have less manpower available to do the rescues and to come out and put out your fire."

I asked Ryan what he would do if he ever had a situation in which he had too many fires to put out. "The State of Oregon has a conflagration law. But a conflagration only pertains to a city." And if Valley Fire were to have 20 houses on fire, he claimed, "they don't have anybody to rely on to call in to help them. If that happened to me or to any other public fire department, we have other resources to call in."

What Chief Ryan was referring to is the well-known practice of mutual aid among fire departments. But when I asked Phil Turnbull about this criticism, he laughed, pointing out that Ryan's city fire department has adamantly refused to set up a mutual aid agreement with the private firm. But Valley Fire does have formal mutual aid pacts with Jackson County Districts 6 and 9, an informal arrangement with Grants Pass Rural, and another informal arrangement with the State Forestry Division. And Turnbull said they are planning to approach two other nearby districts to negotiate agreements in the near future.

At the District 5 Fire Station, Chief Max Long was less critical of private fire services: "I don't have any personal or professional objection to it if that is what the people in that community want," he said. Chief Long affirmed that the tax rates in his district are higher than Valley Fire's subscription rates, but he contended that if privatization of fire services were to become a national trend, "eventually their costs would rise up to the public-sector costs that we are faced with today." He attributed more expensive services in his district to the greater manpower he has on duty—23 full-time employees versus Valley Fire's 9. "A 250-square-mile district covered by 9 paid people is not going to be as effective as a 67-square-mile district covered by 23."

Yet the loss-ratio statistics cited above refute Chief Long's commonsensical proposition. The fact is, Valley Fire's customers are getting much better quality fire protection for about one-fifth the cost.

So, what happens when a private firefighting company fails to satisfy its customers? If they're lucky, a competing firm is allowed to step in. For the evidence is overwhelming that the entry of a second firm has improved the quality of fire protection in the Grants Pass area. Not only have two-thirds of the former company's subscribers switched over to Valley Fire, with its new equipment, professional staff, and much lower loss ratio, but competition has finally forced Grants Pass Rural to improve.

Last May the ISO conducted a grading of fire services in the Grants Pass area. And while a portion of Valley Fire's service area was upgraded from Class 8 to Class 7, the big surprise was that Grants Pass Rural was upgraded from Class 9 to Class 8 in the vicinity of its stations. Having settled with the IRS and reincorporated with a revised board, the company greeted the ISO inspection team with a new tanker, portable radios for alerting fire fighters, and (for the first time) training records. Although only time will tell whether the firm's performance will match its new rating, the turnaround is nonetheless dramatic.

With Rural now able to offer Class 8 rates, Valley Fire can no longer market its subscriptions based on insurance cost savings compared with its competitor. It is now focusing on the demonstrated quality of its service. And as of December, Turnbull reported that contract renewals were running at an impressive 98 percent.

Moreover, the company is not resting on its laurels. Last July it made its first expansion outside its original service area. After the voters of the Sunny Valley Fire District abolished their fire tax, Valley Fire arranged with the district to operate its station and engine. Instead of using tax money, the company is signing up the district's residents on a subscription basis, just as in rural Grants Pass: as of year-end, about a third of the district's households had signed up for fire service.

What the Valley Fire Service experience demonstrates is how effective competition can be in solving problems—even in a public-safety service like fire protection. It seems clear that the level of fire protection in the area around Grants Pass in 1976 was abysmal. The conventional approach, which almost won the day, was to create a fire district with taxing powers and to legislate the faltering company out of existence. Instead, thanks to a brash young entrepreneur—and to the absence of government obstacles—the citizens were given a choice of services, their taxes were not raised, and the level of fire service has improved dramatically.

Grants Pass's unique situation shows us, first, that more government is not necessarily the solution to poor-quality public services. And second, private enterprise is not in itself a panacea. What saved the day in Grants Pass was freedom of entry—the ability to compete. As long as markets are kept open, and free of controls and red tape, consumers are very likely to be well-served by entrepreneurs who are ready and willing to offer essential public services.

Gaines Smith is a free-lance writer and editor. This article is a project of the Reason Foundation Investigative Journalism Fund.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Feet to the Fire."

Show Comments (0)