Sacred Cows—Or Us

Six months ago on this page we said that the federal budget was out of control. Events since then have amply confirmed that assessment. In the face of more than $300 billion in projected deficits over the next three years, Congress has enacted only $30.5 billion in spending cuts (plus $98 billion in new taxes). And in a further confession of impotence, the House has quietly raised the debt ceiling to $1.29 trillion.

No wonder the business community is frightened. In a recent cover story on the "built-in deficit," Business Week agreed that the government "has lost long-term control over the balance between expenditures and revenues." Although federal spending soared in the '60s and '70s, it remained at about 20 percent of gross national product. But it has now jumped to 23 percent and will remain there through 1985. This is cutting back on big government?

This unprecedented diversion of resources to government is destroying our economy, in two ways. First, it is sopping up savings. In 1960 total federal borrowings consumed only 19 percent of net national savings, according to a study by Manufacturers Hanover. But by 1980 this figure had climbed to 73 percent. And in 1983 and 1984 federal borrowings will consume 113 and 107 percent of all savings—and that's assuming that savings grow twice as fast as they did during the '70s due to supply-side tax cuts. Second, it is keeping interest rates high. To the extent that deficits don't crowd out private investments, the Federal Reserve monetizes them by creating new money. It is the fear of such renewed inflation that is keeping interest rates at unprecedented levels, killing off needed capital investment.

The fundamental problem is that our political system is inherently biased toward spending—taking money from everyone to reward favored constituencies. Those interests may be narrow and special—nuclear power, farmers, builders—or they may be broad-based—retired people, for example. Most of the "cuts" thus far have been in the 20 percent of the budget that affects narrow domestic interest groups. Nearly untouched has been the 48 percent accounted for by "entitlement" programs (including Social Security), while defense spending (at 25 percent) has, of course, been going up.

It's to correct this structural problem that the proposed balanced budget amendment has been designed. While the present measure may not be foolproof, the idea certainly makes sense. Because state governments must balance their budgets, more than half of them have cut services and employees this year. Michigan has laid off 10,000 employees and cut spending by 20 percent in real terms since 1980. California's 1983 budget is down for the first time since 1943.

If Congress were held to the same discipline, what would a real deficit-reduction program consist of? Our own five-point program, goring every sacred cow, would go as follows:

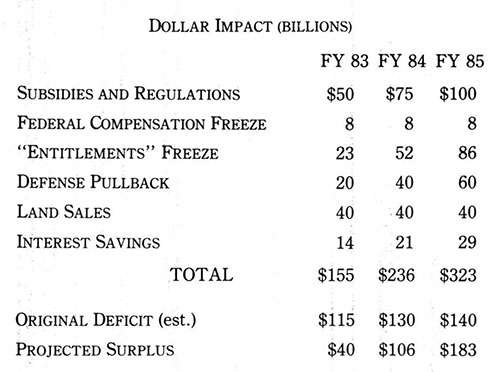

1. End subsidies and regulation. The Cato Institute recently published a detailed analysis of domestic spending programs, identifying $106.7 billion in agencies and programs that regulate, subsidize, and control Americans. Let's assume $100 billion of such cuts, phased in over three years.

2. Freeze federal pay. Simply omitting one annual increase in already-excessive federal salaries and benefits could save nearly $8 billion.

3. Freeze "entitlements." Ultimately, Social Security must be privatized and other federal relief programs (Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps, AFDC, and SSI) phased out in favor of voluntary alternatives. A first step would be to freeze their spending at 1982 levels while transition programs are drawn up. (And if this overall program succeeds in controlling inflation, no one would be harmed much by such a freeze in any case.)

4. Bring the troops home. A five-year phase-out of US forces based in Europe, Japan, and Korea would eventually save $100 billion a year, with first-year savings of $20 billion.

5. Sell federal lands. Just the "surplus" federal lands are worth $100 billion. Adding in some National Forest and BLM grazing lands could yield another $100 billion. Altogether, such land sales could yield $40 billion a year for five years.

The impact of these measures, combined with the savings in interest costs from a smaller deficit, are shown below. Instead of a $115-billion deficit next year, we'd have a $40-billion surplus. Over three years, the surpluses would total $329 billion, reducing our trillion-dollar national debt by nearly one-third.

Such a program would regenerate our decaying economy. Interest rates would plummet, savings would soar, our ailing industries would be rebuilt, and the new high-tech industries (bioengineering, robotics, etc.) would set off a technoindustrial revolution the likes of which the world has never seen.

This result is within reach—but only if we can break the deadly grip of politics as usual. Whether by the voters directly or by a constitutional amendment, Congress simply must be forced to shrink our overgrown government. We can rebuild the American dream—or we can continue to let government consume our substance. Are pork barrels, defense welfare, and "entitlements" really worth that price?

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Sacred Cows—Or Us."

Show Comments (0)