What to Buy in the Coming Depression

A speculator's guide to profiting from the crash

Let me lay it on the line: the Greater Depression has started. I believe it may one day be called that because it is likely to make the unpleasantness of the 1930s look tame and insignificant by comparison. At the same time, it will probably be much different.

This forecast shouldn't come as a surprise to people who know the benefits of a free market. But at this point it should be taken seriously from not only an academic and theoretical but also an emotional and practical point of view.

Many who have some understanding of economics have for over a decade now been expecting, perhaps even planning their lives around, the coming collapse of Western civilization in general and its economic system in particular. The long-awaited retribution the free market "should" visit could have occurred as early as 1970 or in 1974. But each time, government planners have proved extremely clever at holding the system together with the financial equivalent of chewing gum and baling wire.

In fact, one might say that over the last 10 years they've even established a good track record at crisis management. That's something that may cause some complacency, even among those who know a well-deserved financial collapse is inevitable. They have been living with a bomb-shelter mentality for so long now that many are starting to second-guess themselves. Indeed, over the last 10 years, I suspect many have been more hurt than helped by their theoretical understanding of economics—thinking that that was all they needed to join the new class of millionaires that will be created by the collapse. It isn't.

The reason is that many have mixed investment with ideology, while alternating from complacency to frenzy, and that's a formula for failure in the market. Gold has been perhaps the most prominent example of this phenomenon.

I understand how hard it is to be objective about gold, but many people buy the metal for ideological reasons as much as for financial considerations. The ideological gold buyer believes he is doing his part to affirm capitalism and fiscal responsibility. His act defies the Washington socialists, affronts the New York Times, and raises the blood pressure of Federal Reserve Board members. He considers it an act to punish those who don't understand that a government can't inflate without consequences.

For many gold buyers, therefore, gold isn't just an investment; it's a political statement. That feeling is exactly why such buyers always get caught long in gold bear markets. Betting that the gold price will decline—even thinking it—shows a break of faith, they feel, in American ideals. They don't understand that "investment" and "ideology" are two different things. They don't understand that gold isn't a religious relic—it's a commodity. And because this approach to other investments tends to introduce the same distortion, they often make similar mistakes in other markets. They may understand political principles and economics, but they don't understand speculation.

In order to capitalize on the markets of the '80s, you'll do well to adopt the attitude of a speculator who doesn't pass moral judgment on the way things are. A socialist sees government intervention as "good," a free marketeer sees it as "bad," but a speculator doesn't clutter his mind—or, his investment mind—with those opinions. He tries to maintain a scientific, "value-free" approach and doesn't mix investment with ideology.

In a stable free-market society, speculators would be far less prevalent. While there are always natural phenomena, changes in consumer tastes, and technological developments, a major present-day source of profit opportunities—government intervention in the marketplace and the distortions it creates—would be missing. The other side of this coin is that the 1980s have both good news and bad news for everyone. The bad news is that, in an inflationary, heavily taxed, and regulated society such as ours, one has to become a speculator out of self defense. The good news, however, is that the same governmental intervention creates plenty of opportunities to speculate successfully. There is nothing wrong with taking advantage of those opportunities. Price controls, manipulated interest rates, strikes, war rumors, subsidies, and hundreds of other politically related actions all pull the market in predictable directions.

Somehow, speculators have gotten the image of careless gamblers charging about in wild, frenzied activity. It's a totally inaccurate image, at least where the successful speculators are concerned. Good speculators are always low-risk speculators. Far from taking risks, speculators only go in for "sure things." They are rational and unemotional if they're successful; the irrational and emotional who like to gamble and take chances don't last long playing the game, and they soon become exspeculators.

What will be good speculations? Let me cover two things you shouldn't do—and one you should.

First: Stay out of real estate—the crash has a long way to go. Nor do I expect property to recover quickly, because it's such an illiquid investment. In the best of times, it can take months to sell, but in a chaotic environment it can be a drag on the market, hardly the type of ball a broken field runner wants to carry. It's hard to sell unless there's a boom on, and it's always expensive to sell. Commissions, fees, and transfer taxes can easily eat up 10 percent of the gross.

When I wrote Crisis Investing in 1979, a speculative boom was in progress. That crazy peak, in which people exchanged tales of housing values at cocktail parties, has passed, and prices have already dropped substantially since then in most parts of the country. But just because the top has passed doesn't mean that the bottom has come.

The price of houses today, however, shouldn't concern smart speculators, because smart speculators wouldn't own one—at least not as a speculation, because it's now only a consumer good. If you want a house, if it gives you pleasure and you can afford it, buy it and hope for the best; but don't count on it for an old-age pension as most of your neighbors have done. Perfectly sensible people who wouldn't think of buying $40,000 automobiles or $1,000 suits have bought $250,000 houses on their $30,000 salaries. Somehow they can see the expensive suit or car as living above their means, but not the house, because they've talked themselves into believing they're investors. Such is the stuff of economic collapse for a society and bankruptcy for the people who indulge in it.

There are those who counsel that when you rent all you're left with is a stack of rent receipts. But, in addition to their receipts, renters today have a stack of cash they haven't had to pay out. For the next several years, the renter will be in the catbird seat, since he will have neither the huge carrying costs nor the liability that goes with ownership.

The average house in many parts of the country now costs about $100,000. Invested in Treasury Bills, that $100,000 could yield $15,000 a year, enough to rent the same house for about $500 per month (or $6,000 per year) and have $9,000 per year left over. If they save that cash, they'll be in a position to buy houses soon, when the market collapses, because everyone else is mortgaged to the hilt, and the mortgage market itself will soon cease to exist.

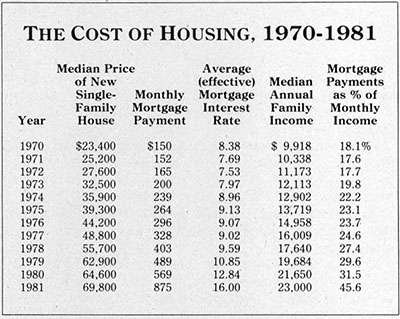

The price of housing and the cost of mortgage money are closely related, like opposite ends of a seesaw. Throughout the '50s, '60s, and early '70s, loans were made to aspiring homeowners on the basis of their income and ability to pay the mortgage. Houses were "affordable" up to about 1976, before they began escalating almost geometrically in price at the very same time interest rates started their move from 9 percent to 18 percent. The more unaffordable housing became, the more people had to borrow to buy it. The table below shows why people will soon be unable to buy, even if loans were available.

Although the price of houses has gone up almost three times since 1970, the cost of buying a house has gone up almost six times. In real terms, counting increased incomes, the net cost of buying a house has gone up two and a half times.

According to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, in 1970 half the families in the United States could afford a medium-priced new house. By 1980, less than 13 percent could. By 1981, the figure had fallen to 5 percent. And most of these families could "afford" the house only if they could get a high-priced mortgage.

Paradoxically, inflation, the very thing that people are counting on to present them with profits, is instead going to present them with huge losses, since inflation will destroy the mortgage markets. And without borrowed money, nobody can buy—or sell—a house. Money will flow wholesale out of lending institutions in the 1980s as the inflationary depression deepens; people will stop saving, and banks will have no money to lend.

If actions have consequences and causes effects, then the expanding crisis in real estate is predictable and inevitable, and it's just the beginning of the collapse. Real estate will be the 1929 stock market look-alike by the time the final bottom comes.

Every real estate booster feels that he has a few aces in the hole that he expects will bail him out. "Pent-up" demand is popular at the moment as a straw to grasp at, although I don't know why. Anyone who looked at the figures would see that the total net population of the United States increased by only 14 million persons from 1970 to 1980, while there were 15 million new housing starts in the same period. Hardly the making of a shortage; rather, a glut.

The housing glut will become evident as the standard of living drops. Lots of "swinging singles" and "young professionals" who are now stylishly living alone in two- and three-bedroom dwellings are going to move in with friends or relatives. Where there was a "demand" for three spiffy townhouses, there will suddenly be a demand for only one, and the other two will either come onto the market for sale or become unrented albatrosses around the neck of an overextended landlord before going onto the market a little later.

Most people still believe that the softness of the market since 1980 is just another "healthy correction" in the 30-year, post-World War II bull market. Don't let them confuse the issue. They'll be the same ones who will think real estate's dead forever after the bottom comes. Be grateful to them for acting as stewards over your property until you can buy it from them for lower prices. New fortunes will be made by those who are shrewd enough to hold their fire until the bottom of the market falls out. Markets fluctuate; real estate's day has gone, but it will return, although probably not before the mid-1980s and from half of today's real-dollar levels. Smart speculators will wait until then. And they'll be very careful what money market funds they'll put their dollars in until then.

Money market funds are the free market's answer to a banking system at the point of collapse. Unfortunately, some of the funds are going to go the way of the banking system. These constitute the second category of investments you want to stay out of.

Most investors seem to think that the money market funds are riskless; they don't seem to understand that funds invest heavily in high-risk, high-yield paper. The public thinks the "best" fund is the one that pays the highest yield, and it's no coincidence that that's usually the riskiest fund. Once again, the public will be taken to school and given a lesson it won't soon forget.

It will be interesting to see what happens when a few funds (actually it's likely to be more than a few when it happens, since most hold the same type of paper) experience some defaults. After some assets are wiped out, the public will start redeeming en masse, which will have some unpleasant consequences for the banks and corporations that have been counting on this pool of funny money to keep rolling over their paper. The default of a few borrowers could cause a credit crunch of unbelievable proportions as other corporations looking to the funds for cash find there's none available. And that would bring on more defaults, which would bring on even more, and so on, ad bankruptium.

Remember that money market funds are mutual funds, only they invest in short-term debt, not stocks. The paper an MMF buys can default. There are seven classes of MMF assets: US Treasury obligations, US government agency obligations, repurchase agreements, bankers' acceptances, certificates of deposit, international certificates of deposit, and commercial paper. The only acceptable MMFs are those that have 100 percent of their assets invested in either Treasury or federal agency obligations or repurchase agreements backed by them. Their yield is generally a bit less, but it would be tragic if you traded safety for a few points of yield today. This entire area could develop into a tragedy for the small, naive saver.

But if real estate is a no-no and only a few money market funds are acceptable, where should you put your money? I believe the answer is the least obvious place to look during the Greater Depression: the stock market. And that, it's no coincidence, is why it will soon be the best place to be.

I was very bearish on most stocks when Crisis Investing was written in 1979. Now, despite the fact that the fundamentals underpinning American business in 1982 are far worse than they were then, I'm looking forward to a time to cover my shorts and buy.

By the end of 1982 the stock market will probably have experienced most of its long-awaited crash. There's little point, therefore, in dwelling on the dangers of the market; most of them already have been realized. Let's concentrate on the profits ahead. The bottom line, despite the continuing collapse of the economy during the years ahead, is that the stock market will boom by the mid-1980s.

In countries with terminal inflation, like Argentina and Israel, everybody who has any spare cash at all is a stock player. It's not only because everybody is forced to speculate but because, as in America, capital gains are given tax preferences, and money made in the market is worth a lot more than salary or interest income.

In this type of hectic environment, the most-liquid mediums tend to be the preferred ones, and funds will flow into stocks because stocks are an ideal speculative medium. But there are other reasons, too.

People will want to be in the stock market because they won't want to be in the alternatives. A flight from currency seems almost certain to occur, and there's a good chance that foreign-exchange controls will be imposed about the same time. Both should benefit securities greatly.

By the mid-1980s, as inflation goes to 30 percent and above, Americans will finally realize en masse that the dollar has been not only the unfortunate investment in the past but the worst possible place to keep assets for the future. In 1982, though, most of the country's net wealth is still held in dollars—cash, bonds, Eurodollars, and mortgages.

Despite the economic collapse all around them, stocks could explode upward simply because that's where a lot of the money leaving dollars will go. Stocks, at least, represent equity.

If this scenario sounds unlikely, remember it wouldn't be the first time. The German stock market lost on the order of 95 percent of its real value from 1918 to 1923 and then moved up by a factor of 10—in real terms—in November 1923, the worst month of that country's famous runaway inflation. But let's hope that's too drastic an example.

Italy provides a more recent and moderate comparison. The US economy is being Italianized; high inflation, high taxes, a ponderous bureaucracy, strong unions—there are many similarities.

The Italian market lost 70 percent of its lira value from the peak in 1959 to the bottom 17 years later in 1977, while the lira itself lost 75 percent of its value. The Italian market thus lost 92 percent of its real value from top to bottom. Italian stocks exploded upward from 1977 to 1981.

Since the 1966 peak of the great post-World War II bull market, the Dow Jones Average has dropped almost 80 percent of its value in real terms, although in dollars it's only declined 20 percent. Now, in 1982, stocks have lost almost as much in real terms as they did from 1929 to 1933. It's approaching the time to buy.

Successful speculators don't take "even odds" bets. If you want to win at this game, you don't move until the odds are loaded at least 60:40 in your favor, with a payoff of 2: or 3: or 10:1 for what you're willing to risk.

The way you make money in a market is by buying when things are cheap—and that means when they've lost the majority of their value and have established a "bad track record." When the bottom of this bear market comes, as it will, you'll want to buy blue chip companies, like those in the Dow Jones Index, which have lost 80 percent or more of their value from their real highs of 1966. After a crash, or during a depression, people are afraid to buy stocks at all; when they do, it's usually only the largest, best-capitalized companies that can attract them.

Especially today, when the government panics and tries to "do something," it will favor the biggest companies with its spending, both because it can deal more easily with them and because it's most afraid of the consequences of their not surviving. They'll be the first to get the money created to restimulate the economy, and they'll be able to spend it early, before the resulting tidal wave of price inflation hits. The resulting price boosts will reawaken investor interest in the market and, combined with the factors I mentioned earlier, should send the stock market sky high despite the fact the economy is collapsing.

The blue chips will treat their owners well—for the first time in two decades—during the Greater Depression. But there will be other groups that should be much, much better: the utility stocks, the gambling stocks, and the penny mining stocks, that will have 100:1 upside potential as both gold and common stocks explode upwards. In the upside-down world of the 1980s, the most-conservative blue chips will become crazy speculations, and the craziest speculations will become the most-conservative blue chips.

Markets of all types will move up and down titanically in the 1980s, as the grand super cycle that began at the bottom of the last depression reaches a grand climax during the Greater Depression. Markets will resemble nothing so much as the bar room scene in Star Wars.

Although the financial system will collapse, all the real wealth in the world will remain; it will just change ownership.

I sincerely hope that ownership will devolve to free-market devotees who not only understand theoretical economics but can apply that knowledge practically as speculators. Good luck, and good hunting.

Douglas R. Casey is the author of the bestseller Crisis Investing and the recently released Strategic Investing (Simon & Schuster). He publishes an advisory newsletter, Investing in Crisis, and provides financial counseling and fund management services.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "What to Buy in the Coming Depression."

Hide Comments (0)

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mute this user?

Ban this user?

Un-ban this user?

Nuke this user?

Un-nuke this user?

Flag this comment?

Un-flag this comment?