Unload the Subways

Taxpayers' billions haven't saved the nation's greatest subway from crime, filth, and deterioration. A noted economist offers New York City a radical solution.

Along Madison Avenue in New York City every afternoon ply an extraordinary variety of buses. There are old GM buses loaned from Washington, D.C., to replace broken new Grummans, new GM buses bought to replace Grummans, and some repaired Grummans. That accounts for the city buses. And then there are buses with names like Domenico, Sternway, Liberty, and New York Bus—private express buses taking Manhattan workers and shoppers home to the Bronx and Queens. They struggle through some of the most congested city streets in the world and operate without subsidies and in direct competition with the subways. And they succeed!

Most of the areas the private express buses serve are also served by subways. A subway will get New Yorkers home for 75 cents. But there they wait, on the sidewalk on Madison Avenue, to ride the private buses and to pay anything from $2.50 to $4.00 for the same journey. While the private buses pay their own way, enlisting the voluntary support of consumers in the free marketplace, the subways forcibly rip hundreds of millions of dollars out of New York taxpayers (and lesser amounts from all taxpayers) for their sustenance.

The willingness of so many people to pay extra for private transport services is just one measure of how atrocious, by comparison, the city subways have become. At the same time, it is a sign that private ownership could provide an alternative to the decaying city-owned underground.

A MARVEL IN RUINS

Consider first that this generation of New Yorkers have come into an inherently great system for getting themselves about. It is now being grossly mismanaged, but as originally developed, it was something great!

Look what was built. As befits the largest city in the world, the New York subways are the largest, most extensive underground rail system in the world. No location in the city is far from a subway. Three separate systems, some 23 lines (plus branches), it has 458 stations and runs 6,500 cars, over 826 miles of track, covering 230 route miles. A billion passenger trips are made on the subways each year; well over 3 million each weekday.

Its tracks climb hundreds of feet onto two huge suspension bridges and dive down into 13 deep and long tunnels beneath the East and Harlem rivers to connect the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens and the Bronx to Manhattan, as if they were one. Much of the system is four tracks, the central two tracks being for expresses, the outer two for locals. Few other systems have that. The stations generally were built immediately below the street pavement, so they are readily accessible—unlike the London "tube" stations, which have to be reached by amazing but slow escalators or even, in places, elevators.

By any standards the construction of the New York subways is an amazing feat of engineering design and execution. Along narrow avenues like Lexington the system is double-decked half the length of Manhattan; the transfer stations where lines cross are intricate rabbit warrens of tunnels for both trains and pedestrians. The trains run fast—55 miles per hour is the regular cruising speed for expresses.

Without the subways, it is doubtful New York would have established itself in the first half of this century as the financial, publishing, fashion, and entertainment capital of the world. This most city-like city of incomparable concentrations of towering skyscraper offices and of blocks of brownstone terrace houses and innumerable apartments and great museums and hotels, all cheek by jowl, could never have developed without such an excellent rapid transit system.

"What is amazing," wrote Paul Theroux recently in the New York Times Magazine, "is that back in 1904 a group of businessmen solved New York's transport problem for centuries to come. What an engineering marvel they created in this underground railway! And how amazed they would be to see what it has become, how foul-seeming to the public mind." For although New York's subways were initiated, financed, built, and initially run by private enterprise, the inheritance has been squandered in four decades of government anti-enterprise.

New York's subways are notoriously bad today, and their condition, like the rubble of the South Bronx, symbolizes the municipal decay that is becoming commonplace in America. As economist James Ramsey expressed it recently: "The entire subway is a decaying filthy mess, more reminiscent of an open sewer than a mode of transportation.…[It is typically] a dimly lit, littered tunnel which drips water and smells of stale urine."

And that's not the worst of it. The subways are unsafe; crime on them is rife. In 1980, the last year for which statistics are complete, nearly 30,000 crimes committed on the New York subways were reported—5,000 robberies, 14,000 larcenies and assaults, 8,000 bag snatchings, 21 murders, and 24 rapes. In 1981, according to a Transit Police spokesman, these frightening statistics increased substantially. All that crime occurs despite a Transit Police force of 3,000 and the good work of the famous Guardian Angels patrols.

Graffiti! No treatment of New York's subways can avoid mention of the mixture of crude spray-can artistry and vandalism that covers every car in the system, inside and out. On the metal exterior walls of the cars and on the laminate inside walling, graffiti are just an esthetic affront; but as they frequently obscure train numbers, destination signs, and route maps, graffiti also create huge practical problems for subway users. They are constantly wondering, Where am I, if I can't see station signs out the window? And where is this train going, anyway, given that all its destination signs are obscured? With the overhead map painted over, how many more stops till my stop? Terse loudspeaker announcements spoken over a crackly address system in a particularly clipped, almost consonantless, Bronx or Brooklyn dialect may be all you have by way of clues in navigating the system.

The biggest problems, however, are not the dirt, the smell, the crime, the graffiti, or the language of the staff. The major, the fundamental, problem of the New York subways is the economics of political mismanagement.

FINANCIAL HEMORRHAGE

It is no small feat to come to grips with the dollar numbers involved. The subways are run as part of a maze of interlocking and overlapping agencies within the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), put together in the 1960s. That organization is supposed to report annually, but as of the end of 1981, when I started researching the plight of the system, the last "annual report" was for the year of 1979! A nonindexed, typed and photocopied document without any page numbers, this is a farce as an annual report. If any such document was submitted by a public company, it would be immediately delisted from the stock exchanges and rightly prosecuted by the Securities and Exchange Commission. But being a government fiefdom, the MTA can, it seems, get away with a financial report the village Boy Scout troop would be rather shamefaced about.

This MTA is responsible not only for the New York subways but for city buses, three major suburban commuter railroads, the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, and two major peripheral airports in the New York area. The subways are owned by the MTA but operated by an agency called the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA), which in turn has as a subsidiary the cumbersomely titled Manhattan and Bronx Surface Transit Operating Authority (known by its acronym MaBSTOA) that runs the city buses.

The MTA reports never make clear when the NYCTA figures include or exclude the buses, but I was assured by an official that an unnumbered page at about the middle of this so-called annual report, titled "New York City Transit Authority, Statement of Flow of Funds," is for the subways only. It shows a "cash deficit" of $293 million. Included in the cash generated, however, is some $55 million in reimbursements from New York City for "reduced fare programs." And on the costs side, excluded are some "transit police, engineering and other services" worth $126 million, financed out of the city budget. So the real cash operating loss was $474 million. That was in the year 1979, remember, the closest I could get with any dollars on paper.

When I expressed amazement to the MTA official about the lack of any report for 1980, she said they did not have the money to print the report! The figures were "available." "You must be able to afford some kind of paper?" I asked. "We have a book called Facts and Figures," the woman volunteered. "That has everything in it." I could get one if I wrote a letter explaining who I am and why I want it…I would, if lucky, receive it in about a month, I thought.

The alternative was to go to the book counter at the TA (NYCTA) subway museum in Brooklyn. The museum itself is well worth the visit for a browse through old subway cars and a look at photographs of the system in the old days. But Facts and Figures—cost, $7.00—turns out to be mainly a history of the system, with the sordid $ sign nowhere to be seen outside a mysterious one-line reference to the TA having a "budget" of $298,008,067 for fiscal 1981.

Back to the MTA woman about the "available" figures for the subways' losses for 1980. She eventually returned my call to say that revenues were $687 million and expenditures $1,117 million—a deficit of $430 million. She could not say whether city contributions meant the actual cash operating loss was much larger. Such is the vagueness of the Transit Authority about the millions it loses, and such is its disinterest in civics notions of accountability to the citizenry.

From various nonattributable sources I gathered that as of 1982 the New York subways are likely to cost around $1,500 million to operate and to generate around $800 million by way of fares (and concession revenues), so there appears to be an operating loss of $700 million. (This compares with a deficit of $755 million for 1982 for the Transit Authority, subways plus city buses, projected by Edward S. Seeley, Jr., in the chapter titled "Mass Transit" in Setting Municipal Priorities, 1982.) Operating loss, however, is not the end of the dismal story of financial hemorrhage.

For almost as long as corporations have existed, they have attempted to account for their consumption of capital during the year of their financial report, so that the rundown of their capital shall be allowed for before striking a profit (or loss). Considerable effort goes into this calculation of "depreciation." Not at the MTA, though! Such elemental good accounting eludes the managers of New York's subways. The word depreciation does not appear in any of the MTA's financial reports.

The nearest thing to an estimate of the subways' annual depreciation must be gleaned from statements by the MTA chairman in 1981 that the replacement cost of the TA's capital assets has been estimated "conservatively" at $42 billion and that, based on the useful life of various elements of the system, "about a billion dollars a year" should be going to maintain its condition. This would probably be an overestimate of annual depreciation of the subways. It covers the 4,200-bus MaBSTOA, and perhaps $100–$150 million is attributable to that branch of the TA. That leaves $850–$900 million annually claimed by the MTA chief as "necessary" capital and maintenance spending.

The MTA does have a massive list of proposed Transit Authority capital spending. "Identified Annual Needs" in a 1980 Staff Report amount to the staggering sum of $1,432 million, for 10 years—that's some $14.3 billion in all. A detailed examination of the list shows that $155 million per year is not subway related. And new subway lines are down there for $195 million annually. The MTA cannot justify the continuance of many of the existing lines and has never attempted a rigorous justification of any of these proposed new lines. The document therefore is in part merely a "wish list" of what the bureaucrats, engineers, and planners of the subway system would like to do in their unreal world of unlimited resources and in the absence of any discipline to undertake outlays only to the extent there are prospective future revenues to match those outlays and offer some reasonable rate of return on capital. No marketplace constraints at the MTA!

It may be true, nevertheless—and I could only make a stab at the figure—that about $600 million annually is currently needed to maintain the New York subways and that a figure of that order should be counted as depreciation. Add that to the operating loss of about $700 million, and you have the subways currently operating at a net annual loss in the $1.3-billion ballpark.

Since the annual number of trips being made on the subways is very close to a round one billion, this means that about $1.30 is being lost on each trip. The subway fare was raised in 1981—after great fuss—from 60 cents to 75 cents. Under present auspices, the system is costing something over $2.00 per trip to run, and apparently state and city, as well as federal, taxpayers are bearing two-thirds of the cost of its operation.

Such massive subsidization is quite unsupportable. The federal government understandably does not see why taxpayers all over America should be forced to pay for commuter service in the Big Apple. New York State and City already suffer economically from over-high levels of taxation, which has been identified as the major factor in the emigration of business and jobs to nearby Connecticut and New Jersey and to the south and west of the United States. The other huge problem in maintaining New York as a vital city is crime prevention, and every million dollars down the subway is a million less for hiring cops.

People might believe that there is a welfare argument for below-cost subway travel for poor New Yorkers, but nothing could be more insane than the present system in which everyone riding the subways gets so heavily subsidized. In short, there seems to be no argument for subsidization of the subways—or for government ownership. It is under government ownership that a grand system built early in the century by entrepreneurs has been brought to the brink of ruin. As argued by James Ramsey, chairman of the Department of Economics at New York University, at a recent public seminar, continuance of government ownership is intolerable; and subway operation by purely commercial businesses would be far superior.

In early 1982, two separate events underscored this conclusion. The publishing firm of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, citing as a major factor the city's unreliable and unsafe transportation system, announced that it will move its headquarters and many of its operations from New York City. And the New York State Court of Appeals ruled that the Transit Authority, as a government body, should not be held to the same standards of care as private bus companies and railroads and therefore is not liable for crime on the subways.

AVOIDED EFFICIENCIES

A major reason for the deepening financial crisis of the subways is the power of the labor union under conditions of government ownership and apparently unlimited subsidization. The Transport Workers Union (TWU) has throughout the history of municipal ownership of the subways had a "closed shop" arrangement with the government, which means that only union members can be hired. The union has an absolute monopoly of the supply of labor to the subway system.

Ramsey cites figures showing how the TWU has benefited from this monopoly position. During the years 1968 to 1979, the consumer price index rose by 127 percent, but New York transit workers' wages and salaries rose by 176 percent and pension payments by 556 percent. During the years 1965 to 1978, New York transit workers' salaries rose 148 percent, whereas nationwide manufacturing industry wages rose by 119 percent, service workers' by 112 percent, and local and suburban transport and public utility workers' by 116 percent.

The high pay of NYCTA workers was not a reward for productivity increases. On the contrary, productivity has declined on the subways as measured by passengers per employee. In the 1960s it was 170 to 180 per day but by the 1970s was below 130. Ramsey cites NYCTA documents showing that most employees do not even theoretically work an 8-hour day. The maximum hours laid down for car maintenance personnel is 6¾ hours and for trackmen 5? hours. The pay, of course, is based on eight hours.

The government subway workers seem to be much overpaid for the skills required. Ramsey cites the example of token booth attendants who in 1978 made $21,888 a year. These people sell the standard turnstile-opening tokens and nothing else. At the same time, intermediate-grade tellers in New York banks were earning $11,767. In addition to rather high basic pay scales, the subways provide their workers with generous overtime premiums, liberal vacation and time-off allowances, and rights to retirement on full pension after 20 years' service.

It is clear that enormous labor savings are possible on the New York subways. The most obvious labor economy, according to a former TA engineer to whom I spoke, is dispensing with conductors on trains and with token booth attendants—about 7,000 workers.

It seems amazing that a system with route lines as long as 35 miles should have only one fare, but that is conditioned by the token-operated entry turnstiles. Even if the fare was right as an average fare, it would, of its essence as an average, discourage economical short-hop travel and overencourage, by subsidization, long-distance travel. So it inevitably causes overcrowding with long-distance passengers and undercuts the financial viability of long-distance competition such as suburban commuter railroads and express buses, while overcrowding city sidewalks by deterring quite economic short-hop use.

The subway system could sensibly move to some form of distance-related fare structure. It could make use of the automated magnetic-stripe tickets, scanned on entry and on exit, like those on BART in San Francisco and on the Washington Metro. It is the most labor-saving system but expensive to install and maintain. Or else it could use the cheaper ticket-dispensing machines, with tickets checked not at entry and exit, which is so expensive either in manpower or in scanning and computing equipment, but by roving teams of inspectors making random inspections, as is the regular practice in European transit. Jumping of turnstiles to avoid fares is rife in New York under the present setup and is said to lose the system perhaps $100 million a year. Deterring fare evaders by heavy on-the-spot fines or arrest might also keep many criminals off the system, further improving the security of passengers.

As they presently operate, the New York subways are grotesquely overcrowded at various times of the day. A new fare system would also enable management to spread passenger load by having off-peak discounts. But the present management of the New York system has no interest in even such a simple, proven device as this.

The NYCTA does say that its future train cars will be designed for one-man operation, so that conductors will not be needed. But it already has in service trains that allow the driver to check that the doors are clear and therefore do not need conductors; yet these all have conductors.

The TA is putting off for as long as possible any labor-saving measures because it wants to avoid difficulty with the union. It has no plans for any modernization of the archaic system of token sellers in booths and token-operated entry turnstiles that limit it to a single systemwide fare.

Privately owned businesses that do not have access to the coercive powers of taxing (or printing money) in order to finance deficits are much better able to resist extraordinary wage pressures and to negotiate with unions more productive work arrangements. In recent months we have heard a lot about airlines, trucking companies, car manufacturers, and other businesses successfully negotiating "givebacks." What givebacks have been gotten from school teachers, fire fighters, bureaucrats, or transit workers? None that I have heard of.

The reason is obvious: in a business enterprise, employees see that its survival and consequently their jobs are directly related to their productivity and inversely related to their cost by way of pay. In a government authority, in contrast, employees see the survival of their operation as almost completely assured whatever their productivity and pay. They see that their agency is already heavily into the pockets of tens or even hundreds of millions of taxpayers. And they see it as capable of borrowing or sponging off of some other level of government. They see no limits to subsidies, hence no constraints on their remuneration or on restrictive work practices.

A risk-capital commercial enterprise will therefore inevitably tend to be more flexible, more efficient, more responsive to consumer demands. And it will, of course, have to be profitable. Those constitute overwhelming arguments for commercial ownership and operation.

Ramsey is well worth quoting for his succinct summation of the case against government operation of the subways: "If we couple the enormous economic power of the union with political leverage, then the ability of the union to tax the rest of society is impeded only by political reluctance to raise fares and the length of debates on tax increases." In light-hearted tone, he formulates his version of Parkinson's law. We could call it Ramsey's Law of Transit Subsidies:

The value of managerial incompetence, waste, and of labor benefits will always exceed last year's subsidy, no matter how large—in fact the larger the subsidy, the greater the deficit now generated.

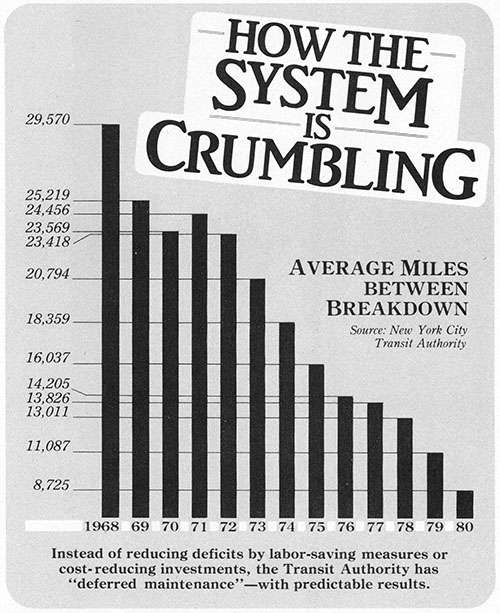

About the only savings that have been made under the pressure of the New York subways' vast and growing deficits have been through what management calls "deferred maintenance." That is the official euphemism for neglecting the upkeep of the mechanical equipment of the system. As a result, trains break down with alarmingly increasing frequency (see graph, p. 24). The MTA reports that on the average day 190 trains never make it out of the storage yards because of defective equipment. Among the 1,215 trains that do get out each day, an average of 140 are abandoned en route because of breakdowns. Doors fail to open or close, brakes fail, motors won't work, signals go out, power pickup shoes fall off. A system once famous for the frequency and reliability of its service has become quite erratic. Waits of 20 minutes are common in rush hours, so that stairways and walkways as well as platforms become jammed with waiting people.

There have been no disastrous crashes yet, fortunately, but this has been more a matter of luck than a result of care. In Brooklyn in the fall of 1981 there was a rear-end collision in the subway when signals malfunctioned, and the motorman in one train was killed. Between then and the middle of March 1982 there have been six derailments—none fatal, but an ominous development.

WHAT MONEY CAN'T DO

The response of the MTA management to this deterioration is to propagandize like fury. Officials do not try to deny or even moderate complaints that the subways are falling apart. They happily confirm them—and harness them to build political support for vastly increased spending. New York magazine, which usually prides itself on its antiestablishment stance, recently ran a pure PR piece supporting the MTA's efforts to rake up $7.9 billion for new plant and works.

Now there is no doubt that capital expenditures of various kinds are needed to bring the subways back into physical and financial health. But all the present government managers want to do is to spend money! They hope to get $1.3 billion from the federal government, almost $1 billion from state and city, $400 million from leaseback tax schemes (now in jeopardy because of attempts to rescind this tax measure), and some $200 million from motorists via diversion of profits made on tunnel and bridge tolls. The balance, some $5 billion, would come from bond issues.

Of the total $7.9 billion, some $2 billion would be used on behalf of new buses for MaBSTOA and new plant and equipment for the commuter lines, so about $5.9 billion would be poured into the subways. The reaction to this in New York so far has been a combination of weary resignation ("they have to do something") and skepticism ("they will never get the money, so why worry"). Everyone concerned about the future of New York should worry like hell that they just might get the money!

If such new debts are incurred on behalf of the existing subway system, the interest bill alone on the bond issues would be at least $500 million a year, and could be $700 million. Very little of the spending will be aimed at cost saving or revenue raising, nice though the improvements—new cars, new signaling, new repair shops, track replacement, tunnel repair, station rebuilding—may be. The great $5.9-billion spend-up—titled a "five year" plan!—is just that, a spend-up. It is not accompanied by any set of proposals to cope with the underlying managerial and financial disease afflicting the subway system. There are no plans for reducing services where demand has dropped, no discussion of abandoning money-losing lines, no revisions of operating procedures to lower costs, no new fare structures or systems to encourage more economical use of subway resources, no proposals for labor saving.

The deficits of the New York subways and the burden they impose on city and state budgets can be expected to increase even more rapidly if the MTA gets away with its grandiose scrounge, borrow, and spend-up plans. Meanwhile, every inadequacy of the subways, from minor irritations to major catastrophes, can be blamed by the MTA on a "lack of money." The existence of an unfulfilled "five-year plan" will provide a scapegoat for every problem, a diversion for every complaint.

The fundamental problem of New York's subways is that they are government-owned and -controlled and therefore the constant subject of politics. The transfer of the subways to private ownership is essential for their survival. Ramsey's presentation of the case is worth quoting at some length.

The management of privately owned firms is far more efficient than that of publicly owned or controlled firms, simply because of the difference in the pressures faced by management in the two situations. In publicly owned or controlled firms not only are there fewer and smaller personal incentives to be efficient, the fact of political control adds a further and in the end, disastrous thrust to political myopia, to the acceptance of the expedient response, and to seek to solve today's difficulty at a greater cost tomorrow. This is because the time horizon for the payoff from political decisions is very short, often less than a year and seldom greater than a couple of years,…therefore the political reluctance for the long-range solutions.…Better for the politician to curry favor now and leave the problems to the next election, the next administration, the next generation of users. Better a popular stance on low fares today.…

THE RISE AND FALL

How did politics and government come to thwart and then to distort what private enterprise built in New York's subways? A little history is instructive.

New York could have had subways as early as London, in the 1860s, but politicians protecting established transit interests—horse-drawn trams and then elevated railroads—delayed their introduction for nearly half a century. Declared a frustrated subway enthusiast, Simeon Church, in the 1870s:

Every year the legislature has been the unceasing battleground of rival interests. All manner of schemes have been pressed with all manner of pictures, plates, drawings, models, and designs, endorsed by imposing certificates, bearing imposing and illustrious names, and urged year by year upon the public and upon the legislature, with all the strength of earnest conviction, supplemented by vast material resources and interests, and yet here we stand, with absolutely nothing done.

Hugh B. Wilson, one of the early railroad tycoons, was one of the first wanting to finance a subway in New York, in 1860. By then the population of the city was 700,000, and it took an hour by horsecar to get from downtown (the Wall Street area) to what were the fringes of development (now Midtown or 40th Street) where the train terminals were. Wilson proposed a subway under Broadway equipped with glass sidewalks for light and hollow lampposts for ventilation. His rival Cornelius Vanderbilt, who had interests in the existing street transport, declared, "I'll be underground a damned sight sooner than that thing." With other entrenched interests, Vanderbilt controlled the original Tammany Hall Democratic machine that ran New York City Hall, from the time of Bill "Boss" Tweed. Through the whole of the period 1860 to 1900, politics prevented subway construction.

In the end, the political processes succumbed. The first subway, which opened in 1904, was built for its speed ("To Harlem in Fifteen Minutes" was the political and the sales pitch) and cheapness (a "nickel fare," compared to the normal fares of 7 cents to 10 cents for elevated trains and "horse buses"). The first two subway systems, the IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit) and the BMT (Brooklyn Manhattan Transit), were privately financed, though the city kept title to the tunnels and stations. Good profits were made, and these two companies built most of the present amazing system in barely 25 years.

But by the 1920s inflation became a problem as City Hall insisted on maintaining the nickel fare. Mayor John Hylan campaigned vigorously on a platform of "keeping the nickel fare," and a consumerite "Hylan Five Fare Club" lobbied for the fare ceiling. At the state level, Gov. Nathan Miller enunciated the principle that "profitable parts of the system must maintain the unprofitable." That, of course, was to prevent it being run as a proper business, since the closure of operations not supported by the public (at the farebox) is essential. Mayor Hylan had been fired as a driver on the BMT, and it was said that that motivated his hatred of the companies. In any event, the city pressed ahead alone on a third system, the IND (Independent), which began operations in the early 1930s. The city probably overbuilt.

In 1940 the IRT went broke, unable to make it under fare controls, and the BMT was claimed by the city to be in breach of its franchise contract. Both were taken over, and for over 40 years the New York subways have been run by government agencies. Their present physical deterioration and stupendous losses are the despair of New Yorkers—a great pity, because they constitute a great inherited asset that in present hands is being steadily squandered.

The ideal solution: an unconditional sell-off of the subways, line by line, with guarantees of noninterference in their commercial operation. At a recent public seminar at New York University, James Ramsey presented the free-enterprise case for a subway sell-off and sketched a plan for going about it (see box, p. 31).

In private operation, the subways would face strong competition from surface transport and possibly, in parts of the city, from parallel subway routes run by rival operators. Private owners would thus—and rightly—face great pressure to respond to travelers' wishes, to adapt, and to restrain costs. Compared with the MTA, they would have an enormous advantage in dealing with employees and unions because of their very financial vulnerability. They would of financial necessity run a far more consumer-oriented and economical, though not necessarily a cheaper, service. They might, of course, go broke. Operators that did go out of business would have shown either their incompetence or the lack of an economic demand for the service. There must be no artificial maintenance of service. Cross-subsidization from bridge and tunnel tolls and tax support should cease. Unsaleable or unsuccessful sections of subway would be closed down and offered for other uses.

SELLING THE SELL-OFF

A widespread reaction to the sell-off proposal is that it is "too radical." To which the answer is, Does history, analysis, and logic suggest that anything less radical offers real hope for improving subway service and slashing the costs it imposes? Is anything less radical realistic? Given the massive inertia of an enormous city monopoly agency, why should we believe in the achievability of reform under the present system?

What is radical at one time and place may seem commonplace, commonsense at another. In a large portion of the world the idea of having any railway service at all operated commercially is regarded as bizarre and radical. In my country, Australia, railways were entirely governmentally owned and operated until the 1960s, when iron ore companies built lines from their ore deposits to the loading ports on the northwest coast. In Australia, as in Canada and Japan, broadcasting is part commercial, part governmental, but in much of the world—including some relatively free countries such as West Germany, France, and Israel—governmental monopoly operation of broadcasting is regarded as the norm, and proposals for private ownership are described as "radical."

Of course, there are no glowing examples to be cited of successful privatization of a subway system. But since when has lack of precedent worried New York? The Empire State Building, Grand Central Terminal, Wall Street, the Waldorf Astoria, Radio City Music Hall, Mayor Koch—New York has got all sorts of extraordinary things without there being precedents. The day lack of precedent is seen as a decisive objection to anything serious will be the day to declare the death of New York!

Feasibility? The interests arrayed against a subway sell-off are obvious and formidable. These include the Transport Workers Union, which controls the many privileged jobs at stake; the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which owns and plans the system; the Transit Authority, which operates it; and many of its subsidized users. Many riders detest the present disservice they receive and would probably say that any change could only be for the better. It would be idle, however, to deny that many others of the three million plus daily users have learned to live with the system as it is and would be rather easily mobilized politically against a sell-off. They would prefer the service, bad as it is, and the heavily subsidized fares, to their image of a commercial system.

In practice, of course, the status quo cannot be maintained. Fares are having to be rapidly raised under the present management. But that will not stop the supporters of a municipal monopoly from having a field day with scare sloganizing about business ripoffs, monopoly exploitation, and all the other familiar populist swear phrases.

The ideas in favor of the status quo are probably a greater obstacle to change than are the special interests. Once the battle of ideas is won and enough opinion makers and enough of the electorate are persuaded of the case, the politicians will not be too long in legislating against the vested interests. We have seen that when government regulation gets to be widely perceived as a racket against the public run by vested interests, it gets abandoned. Similarly, when government ownership is seen as an interest-based racket, it too will not last long.

But what of the financial feasibility of the proposal? Perhaps the most common objection to a subway sell-off is that no businessman in his right mind would consider taking it on. Kenneth Orski, president of the Washington-based Corporation for Urban Mobility (an organization seeking to "encourage public/private cooperation in transit"), says the Ramsey proposal is "good for its shock value." But "what serious group of private investors could be interested in acquiring the system in its present state of disrepair?" he asks. Which is exactly the reaction also of the MTA, voiced by Arthur Perfall, director of public relations: "There don't seem to be a large number of buyers out there for a system in which fares only cover half the operating costs." Could subway lines be run at a profit?

It would be a surprise if all of the existing system could be run profitably. After all, most of the privately financed lines were complete by the mid-1920s, and there have been huge population and employment shifts since then—notably, declines in population and jobs in the Bronx and Brooklyn, but increases in Queens and Staten Island and in counties beyond the city line. It is said that the municipally financed IND system, built mainly in the 1930s by city politicians hostile to the IRT and BMT company systems, was designed specifically to drive those companies out of business. So antibusiness politics may have led to the subways being overbuilt, at least to the extent its layout has been ossified around the original IRT and BMT lines.

We cannot be sure of the answers to these questions until entrepreneurs are given the chance to bid on and to operate subway lines. Some projections can be made, however.

We know the present subway system is providing rides at an average cost of slightly over $2.00 (although the price to the rider is 75 cents—as of March 1982). Any commercial organization would quickly make a number of quite obvious reforms to lower costs—one-man train operation, elimination of token-booth selling personnel, and payment of market wages. Distance-related fares would put an end to the overcrowding of terminals and raise revenue more in line with costs, as well as enabling more short-trip riders to be attracted. More rational tradeoffs between capital replacement, maintenance, and breakdowns could be made quite quickly. Management would have its mind focused on positive matters of serving the public. Present MTA management, by contrast, is preoccupied with producing a flow of propaganda directed to squeezing more money out of government.

With privatization of the subways, it is not unreasonable to guess that costs might be reduced immediately by some 20 percent and after a couple of years by something like 35 percent. Competitive commercial airlines in the United States operate at approximately half the cost of the government monopoly airlines of Europe. Deregulation of trucking, taxis, and liquor sales commonly brings about a reduction of costs (and prices) to between 60 and 80 percent of those that prevailed before the pressure of competition and free entry.

On that basis, we could conservatively guess that average New York subway ride costs would go from the present $2.10 to the range $1.40 to $1.70. It seems that certain commercial operators would be well placed to maintain present levels of patronage at those kinds of average prices, (say $1.50 to $1.80), given the existing strong demand for "express bus" seats priced at $2.50 and above. The subways, when running, are still far faster than any surface alternative in New York, such is the state of congestion on the roads. So they start with that great advantage. Use of a private car for a round trip into Manhattan involves parking costs of $10–$20, plus unruly, bad-tempered, bumper-to-bumper traffic. The "express buses" are express only in the sense that they do not open the door en route to take on extra passengers. They are far from being speedy!

I consulted several economists, and all express "in principle" agreement with private ownership of transit. Charles Lave of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology stresses that the civil service works at enormous disadvantages in trying to manage a transit system. He says it is commonly accepted in the transport economics profession that New York's subway management has been plagued down the years by mayoral politics. Gabriel Roth of the World Bank, while reluctant to comment directly on the New York system, says a sensible public policy approach to all transit is to let private promoters take the risks and put up the money. He says municipal- and state-promoted transit systems have never been known to produce benefits greater than costs.

Milton Pikarsky, director of transportation research at the Illinois Institute of Technology and former senior officer of the Chicago Transit Authority, observes that the problems of the New York subways are the general problems of municipalized transport. Private transit operators, for example, can get workers for $5 or $6 per hour, while metropolitan agencies generally pay $10 to $12. "Monopoly, municipally owned transit authorities have reached the end of their useful institutional life," he says. "The only serious question is how they will end." Will they be "put out of their misery" in an orderly, piecemeal way? Or will they be allowed to collapse "in an apocalyptic crisis"?

James Ramsey argues for a one-stage decision process, one big leap to private ownership and operation of New York's subways, although the actual transfer from MTA control would be phased in over five years. There might be advantages, however, in pushing instead for a "demonstration sell-off" as a first step. Further privatization could await experience of commercial operation of the test case and debate over its merits in operation. There is nothing like a live specimen to prove viability!

It happens that the old IRT lines are built to lesser car lengths and widths and to tighter rail curvatures and to this day have different equipment from that operated on the BMT and IND systems. So some or all of the IRT lines would be obvious candidates for the demonstration sell-off. The IND consists of three main lines (two of which have major branches in the Bronx and Brooklyn).

The Seventh Avenue IRT (known as such because it follows Seventh Avenue in Manhattan from Times Square down to Greenwich Village) would be ideal as a private enterprise competitor with the MTA system in that it closely parallels the MTA's IND lines all the way from the northern Bronx through Manhattan and out to east Brooklyn. The IRT's Flushing line that goes east from Times Square through Grand Central into northern Queens has IND and BMT lines close by it most of its length. So the sale of those IRT lines would provide head-on competition, MTA versus private enterprise.

Sale of the Lexington Avenue IRT lines, by contrast, could raise cries of "monopolization," since at least on the eastside of Manhattan, this system has no other competing subway within miles. It was once paralleled closely by the Third Avenue "el," torn down in the 1950s. It was to have been replaced by the Second Avenue subway, most of the tunnels of which were built in the late 1960s.

The never-completed Second Avenue subway should definitely be sold off, for completion as a subway or for some other use, instead of moldering away unused, being forgotten as the MTA's first great fiasco. Just after the MTA was formed, work began on this never-to-be-completed line, and the early disposal of the tunnel and station works would be a fitting gesture for beginning the big subway sell-off.

Peter Samuel works in New York City as a journalist. A native of Australia, he arrived in New York in April 1980 and writes on American affairs for Australia's leading weekly newsmagazine, The Bulletin, and some Australian business publications. This article is a project of the Reason Foundation Investigative Journalism Fund.

THERE IS A PRIVATE SUBWAY

James Ramsey may not know it, but private subway lines have not died out completely. In fact, an entirely new subway was built in Fort Worth in the 1960s by Leonard's Department store.

Like many downtown stores at that time, Leonard's was suffering from the growth of the suburbs. To make shopping downtown more attractive, the store's owners wanted to add a huge parking lot or garage. Land next to the store was fully built up, but 24 acres were available a quarter of a mile away along a riverbank. That location, however, would have been much too far to expect customers to walk.

Consequently, Leonard's built a subway line to connect the lot to the store. The line traverses the parking lot's 24-acre expanse, providing four covered terminals, then goes underground for the trip to the store basement. Five St. Louis Car Company transit cars were ordered for the line and remain in service today.

The subway operates six days a week, charging no fare. The present owner of the store, the Dillard's department store chain, figures it's good business to continue the former owner's policy of providing convenient parking access with the subway line. It even lets nonstore customers ride the line at no charge, simply out of good will.

One final point: the store did not invoke the city's eminent domain powers to acquire the right of way for the line. In true free-enterprise fashion, it purchased the rights to tunnel under several properties and under two of Fort Worth's main streets.

—Robert Poole

THE RAMSEY SELL-OFF PLAN

"There is no sum of money, no subsidy so great, which cannot be eaten up by union demands and managerial inefficiency.…What is needed is some device which will limit union demands to the bounds of reason and concentrate the mind of management on trying to generate an efficient system which serves the public. The following suggestion produces this necessary miracle.…"

So saying, James B. Ramsey, chairman of the department of Economics at New York University and director of the C.V. Starr Center for Applied Economics, introduced his plan at a recent public seminar at NYU. "The fundamental elements of the scheme," he explained, "are that there are to be no price controls, no entry barriers to new subway firms other than those dictated by safety, and the city is to share in the profits of the system."

Then he suggested some details:

- The subways would be sold off line by line over a five-year period, with approximately one-fifth of the system sold each year.

- A group of evaluators chosen by the city and by potential buyers would first put together packages of line and equipment that might operate as independent units and would assess the market value of the capital stock of each package.

- The assessed capital value of a package would have to be paid by the new owner-operator.

- Interested parties would compete on the share of gross profits (net of capital costs) offered to the city. (Ramsey cited a parallel with a California oil-lease sale where this sort of bidding was used.)

- The terms of sale would provide for no future government involvement beyond the policing of public safety. All decisions about levels of service, types of equipment, fares, and what lines and stations to operate would be left to the owners, responding to market conditions.

- There would be no guarantees of protection from competition, no bail-outs in case of financial difficulty.

To separate welfare considerations from the problem of saving and revitalizing the subways, Ramsey proposed that the city could, if it so chose, use its share of profits to compensate the poor for increased subway fares.

Present at the seminar at which Ramsey spoke were representatives of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and city government, transport planners, and other interests and experts. While many expressed political dislike of or skepticism about the sell-off scheme, none could fault its essential logic or come up with any persuasive alternative.

—Peter Samuel

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Unload the Subways."

Show Comments (0)