Fighting With Failures

Why do faulty weapons still pass muster? The Pentagon cheats on the tests.

We will never know how many Americans killed in Vietnam were lost due to enemy fire or to the politics of the Pentagon bureaucracy. We do know that the Army sent soldiers to Vietnam knowing that their most commonly used weapon, the M-16 rifle, would fail. And the Pentagon sent to Vietnam a tank, the Sheridan M-551, that was giving the Army serious difficulties.

The unreliability of the M-16 rifle had been thoroughly established and documented in field tests at Fort Ord in 1965. Even though the solution was a simple change of powder, the Army sent the unfixed rifle to Vietnam. There it jammed frequently enough in combat to induce soldiers to write to their parents, girlfriends, and members of Congress to complain about their rifles and about their buddies dying with jammed rifles in their hands. After numerous lives were lost because of this failure, Congress held extensive, yet not well publicized, hearings on the tragedy.

Paul Hoven, a helicopter pilot in Vietnam, claims that he "never recalled seeing a captured Viet Cong using an M-16," although the Viet Cong would use all types of old captured World War II rifles. He saw the rifle jam "all the time" in use by his door gunners, the crew covering the sides of the helicopters from attack. He himself used a captured Viet Cong rifle rather than risk his life with a jamming M-16.

If Hoven had been a tank commander in a Sheridan M-551 light tank, he would have felt no safer. According to the first official report on the tank, it had 16 major equipment failures, 123 circuit failures, 41 weapon misfires, 140 ammunition ruptures, and 25 engine replacements. For the tank's main gun, the Army used a "caseless" ammunition that was unsuited to the high humidity in that part of the world, so gunpowder would sprinkle down inside the tank around the soldiers' feet—a problem that could make the tank a rolling bomb during enemy fire.

Like the M-16, the Sheridan was extensively tested before it was sent to Vietnam. The Army Test and Evaluation Command listed numerous combat safety and effectiveness problems, yet it continued to roll off the production lines. The program was termed a "billion dollar boo-boo" by Rep. Samuel Stratton (D–N.Y.) after an intensive investigation in 1969, again prompted by soldiers' complaints from Vietnam.

In the years since the Vietnam war, there have been many in-depth analyses of the "lessons" in foreign policy and national character learned by the United States. Sadly, a lesson of vital importance to our future national security has been overlooked or covered up: why the Vietnam war was full of examples of weapons failures and unrealistic weapon systems that cost in tax money, unfulfilled military missions, and our soldiers' lives.

What is supposed to protect the soldier and the taxpayer from a "dream weapon" that fails miserably in the real world? The Pentagon calls it "operational testing"—a series of realistic battlefield tests meant to weed out turkeys before they reach the soldier in the field. But it was deficiencies in operational testing that kept the Vietnam weapons failures from being caught. In spite of countless lives lost and weeks upon weeks of congressional hearings and repeated critical reports from the General Accounting Office, those deficiencies still exist today.

HOW DO YOU BUY A WEAPON? As a defense "ombudsman" for a nonprofit taxpayer organization, I have had a first-hand opportunity to see what drives the Pentagon and Congress to continue to buy and use weapons that will fail. I first became acutely aware of this problem while investigating the Army's new main battle tank, the M-1. One could hardly find a more revealing case study of the way operational testing has been so deformed by the Pentagon bureaucracy and porkbarrel pressures that soldiers continue to end up with weapons that will fail them on a battlefield.

The process the Pentagon uses to procure our weapons is an enormous bureaucratic mass, full of charts, chains of command, and acronyms. But in a simplified form, the basic components of buying a weapon are these:

First, after a service (Army, Navy, or Air Force) decides, with congressional approval, to build a weapon, a program manager is selected. He sets up an office with a staff of perhaps 200 to 500 people in the research and development command of the service to implement the development and production of the new weapon.

At "milestone" points scheduled by each service, it is decided whether or not to continue with the weapon. At Milestone I, the initial decision to begin the program is made. Between Milestone I and II, advanced development begins, with separate components of the weapon being developed at the same time. At Milestone II, the issue is whether to proceed into "full-scale engineering development" (usually a billion-dollars-plus commitment). Few weapons are ever cancelled once full-scale engineering development is approved. Between Milestone II and III, the prototypes are redesigned and tested to provide the basis for a production decision. At Milestone III, the service decides whether to engage in limited production and further R&D or to proceed to full production of the weapon.

The milestone decisions are made in each service by a council representing several appropriate commands. Those decisions are reviewed by DSARC, the Pentagon's Defense System Acquisition Review Council.

Where does testing of weapons fit in the milestone maze? There are two types of testing, developmental and operational. This is how Russell Murray, former head of Department of Defense Program Analysis and Evaluation described the difference between them to the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee in October 1981:

The object of developmental testing is to find out whether a new weapon meets its technical specifications. The object of operational testing is to find out if the weapon—even if it does meet its specs [specifications]—will really be useful in combat.

Developmental testing is conducted by highly trained scientists, technicians, and specialists under tightly controlled, laboratory-like conditions. Operational testing is conducted out in the field by run-of-the-mill servicemen under conditions simulating wartime as closely as possible.

So it is the operational tests that are supposed to protect the soldier from exotic-weapon nightmares. After Milestone II and the full-scale engineering decision, operational testing should be more important than developmental testing and should be one of the major factors in any production decisions.

But when we move out of the ideal world of chains of command and reporting channels and decision schedules, we find that the system doesn't work as it's supposed to. In the real world of politics and bureaucracy and porkbarrel, it is doing no better than it did with the Vietnam era's M-16 and Sheridan tank. The system is still promoting expensive and ineffective weapons at the expense of our soldiers.

David Hackworth, a former full colonel in the Army who served in Vietnam and was considered one of the Army's top counterinsurgency experts, recently wrote in the Washington Post of this new generation of weapons:

My bet, unless cooler heads prevail, is that during the next five years America will spend $1.5 trillion replacing Vietnam era junk with a new generation of junk. It will be more wonder junk—the latest marvels of the dreamers and schemers. The kind of junk that the military has been saddled with since the end of World War II.…As Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger ponders such difficult problems as the B-1 bomber program versus the Stealth and the $75 billion MX missile scheme, I would like to repeat the words of a country boy corporal when he first saw Taylor's incredibly expensive Davey Crockett nuclear rifle: "Sir, that thing just won't work on the battlefield. " A few years later, of course, it was returned to weapon wonderland with thousands of other harebrained, half-baked flops. Luckily it came between wars and nobody was hurt except the taxpayer who paid millions for it.

Included in this new generation of weapons is the Army's M-1 Abrams tank—and we're not talking millions, but billions, of taxpayers' money. From January 1980 to January 1981 alone, the price of the tank, which has a nine-year history of cost overruns, rose from $1.5 million per tank to $2.5 million per tank-a million-dollar jump per unit in just one year. The cost of the tank is now around $2.6 million per copy—and growing. So to buy the planned 7,058 of the new wonder tank, being built by the Chrysler Corporation, the taxpayer will shell out at least $18 billion before the Army is through.

The M-1 tank program caught my eye early in 1981 because of its dramatic increase in price. Although a new tank may not be as glamorous an item to buy as a new jet or missile, several military sources have impressed upon me that it could well prove to be a more decisive factor in any war in the near-term future (although you will never get the Air Force to admit that). While many different aspects of the buying of the M-1 tank are open to criticism, the way it was tested and the way the test results were reported to Congress are dramatic illustrations of what is wrong with our testing and procurement bureaucracies in the Pentagon.

WHAT'S IN A TANK? Known until recently under its experimental designation, the XM-1, the M-1 tank is the Army's third attempt in the past 15 years to build a new tank. Congress had turned down two previous attempts, the MBT-70 and the XM-803, as too costly and too complex and too failure-prone. So the Army's technical reputation was at stake when the M-1 program was formally begun in November 1972.

The M-1 has many new "wonder" features that the Army claims improve significantly on the current M-60 series' survivability, effectiveness, and mobility. These features include new "magic armor," called Chobham armor, made of a classified superalloy reinforced with fiberglass; "fire-resistant" hydraulic fluid; and a fire-detection and -suppression system that is supposed to put out fires in the tank, including the engine, automatically. Its laser range finder tells the gunner instantaneously how far away an enemy target is, and its thermal imaging system assists targeting in darkness, smoke, and dust. The firing system is computerized, and, to improve shoot-on-the-move accuracy, an elaborate stabilization system keeps the tank turret pointed at the target when the tank is rolling. Although the tank weighs in at 60-plus tons, its 1,500-horsepower gas turbine engine (similar to that in an airplane) allows it to attain a speed of 45 miles per hour on a flat road.

All these items have helped to push up the program unit cost of the M-1 to three times that of our standard M-60A1s. But what we're getting, says the Army, is the largest, fastest, and best tank in the world, crucial in any attempt to meet the "projected Soviet threat."

Do the complex new features improve battlefield effectiveness? In June 1981, six NATO countries held a "tank Olympics" in West Germany. The Americans' performance was feared by competitors because their M-60A3 tanks were outfitted with a thermal imaging device and a laser range finder similar to the new equipment in the M-1. The English also entered their tank with a laser range finder.

None of these advanced devices was included on the German-made Leopard IA4 and IA3 tanks entered by the Germans and the Belgians. The Germans, who have won these contests in the past, said they placed emphasis on training and tactics—and they won again in this contest, with the Belgians second and the Americans third. As Defense Week reported: "The competition is a test of marksmanship, yet the laser rangefinder in the U.S. and British tanks seemed to help them little. 'The optical rangefinder is better,' asserts a German tank commander."

So it is important to realize that the complex new features do not necessarily increase effectiveness in a real match and under high pressure. In this case, tactics and training won over new electronics systems. Furthermore, these advanced technologies increase maintenance and spare-parts headaches and decrease the percentage of weapons ready to fight. Keep this in mind as we go into the details of the M-1 tests.

If you strip away all the fancy additions and the computer-age refinements, you come down to a very few basic characteristics of a useful tank. First and foremost among these is the ability to move immediately and quickly at all times. This, in turn, requires that the tank run consistently and reliably under adverse combat conditions with few breakdowns. When the tank does break down, it must be easy to fix quickly. The Army calls these characteristics RAM-D (reliability, availability, maintainability, and durability). The RAM-D requirements for the M-1 have caused the Army a lot of grief, but they could also mean life or death to the soldier in the battlefield.

In Operational Test I (OT I) on prototype tanks in 1977, the Army found that the M-1 was having a lot of trouble with its RAM-D requirements. As a result of congressional pressure, continuations of OT I in 1978 and 1979 stressed RAM-D, and the Army extended OT II to check prescribed fixes for the RAM-D problems. Looking into this is where I ran into a key problem with our weapons procurement: institutions that begin to deform test data before they are transmitted to decisionmakers in the services, the Pentagon, and Congress.

GRADE INFLATION In April 1980 the Army issued a report on the final phase of OT II testing of the M-1 at Fort Knox, Kentucky, in late 1979. When you glance through the executive summary, the tank appears to have been doing quite well. However, the data and comments in the rest of the thick report are a cry for help about a weapon system with serious problems.

The total mileage for the test was 16,070.4 miles, racked up by three tanks. During the testing period, 1,007 maintenance actions were recorded. Taken in raw form this would mean that the tank had a problem approximately every 16 miles. Of course, it is reasonable to conclude that at least some of these maintenance actions, which can range from changing a light bulb to replacing an engine, were not occasioned by major problems that would be serious in combat.

The Army, however, takes this logic far beyond the reaches of reality. In interpreting the raw data from the Fort Knox tests, the Army's "scoring conference," a group of senior officers and civilians from various commands, threw out all but 171 of the 1,007 maintenance actions. This made the tank have a "chargeable" maintenance failure every 93.97 miles for the Army's definition called "system reliability," or, as the Army says, 93.97 mean miles between failures—MMBF. It just happens that the goal the Army had set for itself for this point in the tank's development was 90 miles between failures. (Note: the Army has another mission criterion, called "combat mission reliability," and in grading the tank in this area the scoring conference threw out all but 56.2 of the 1,007 maintenance actions and had the tank going 285.95 MMBF versus a required 272 MMBF).

When I saw these numbers in the OT II report, I thought that perhaps the scoring conference knew something about the tank of which I was unaware. But as I flipped through the computer printout of the failure log, I noticed that the operational test director (the officer out in the field directing the test of the tank) had also noted which tank failures required immediate maintenance so as to ward off much worse trouble. He did record these failures, and when I divided his number into the 16,000 miles of driving covered in the test, I found that the M-1 failed seriously every 34 miles.

The Army, of course, was not happy when I pointed out to members of the press, and they reported, that the tank was really failing every 34 miles, instead of the 93.97 miles claimed by the Army's scoring conference. But I found that I was not the first person to catch such "grade inflation" by a scoring conference.

In April 1980 hearings before the Defense Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee, Rep. Jack Edwards (R–Ala.) had been disturbed by "discounted" failures of the power train (the engine, transmission, and final drive) in the first phase of the OT II testing. During the hearing, Congressman Edwards handed a list of recorded but discounted failures to Army Gen. Donald R. Keith, who was explaining to the committee the M-1's progress:

(a) June 27, 1979, engine no. 47, catastrophic failure—discounted.

(b) August 13, 1979, engine No. 50, catastrophic failure—discounted.

(c) August 23, 1979, engine No. 33, major failure—discounted.

(d) September 26, 1979, engine No. 51, major failure—discounted.

(e) July 6, 1979, transmission No. 27, catastrophic failure—partially discounted.

(f) July 5, 1979, transmission No. 21, catastrophic failure—discounted.

(g) August 27, 1979, transmission No. 17, catastrophic failure—partially discounted.

General Keith was not prepared to give Mr. Edwards an explanation during the hearings but later submitted to the committee the following:

That is correct, these failures were discounted by both the Scoring and Assessment Conferences. Remember that our objective is to determine the inherent durability of the power train itself when it is operated and maintained properly. Other components which cause the power train to fail as a result of their own failure are not charged against the power train. Instead, these other components are assessed in accordance with the XM1 reliability scoring criteria.…Although these failures were discounted, corrective action was taken in every case through either a hardware or procedural change to preclude recurrence. In those instances where partial discounting was indicated, changes had been made and sufficient test miles had been accumulated on the new item to show that the problem had been partially corrected. In the case of the transmission (#27) with the thin wall casting, checks of production castings demonstrated that there were no recurrences. So, the bottom line is this: only inherent design faults are charged against power train durability, but corrective action is taken to preclude recurrence of all pattern type failures. [Emphasis added]

General Keith claims that the Army was trying to test only the inherent design problems of the power train. But remember, that is the purpose of developmental testing. In OT II the Army was well into operational testing that is supposed to assess the tank, warts and all, in a combat-like environment. The soldier under enemy fire is not going to care whether a catastrophic failure in his tank was caused by what General Keith calls an "inherent design fault" or by what a scoring conference thinks is a "nonchargeable" incident. In either case, he may well be dead.

Even after invoking the help of the scoring conference to improve the reported power-train durability, the Army fell way below its own requirement. The Army specification was that 50 percent of the tanks go 4,000 miles without overhauling any portion of the power train. At the end of OT II, only 22 percent of the tanks could do so—this figure was without the failures Congressman Edwards had asked about.

Later tests would show that the "corrective action" emphasized by General Keith did not improve the power-train durability. The probability of operating for 4,000 miles without an overhaul actually went down during the first part of Operational Test III. And in the final results of OT III, the power-train durability figure was 15 percent after scoring.

As for system reliability, the Army's reporting of OT III Fort Knox tests shows the same grade inflation that I'd found in earlier operational testing. This time, the scoring conference rated the M-1 tank at 160 mean miles between system failures, up from 93.97. But when I went through the OT III failure log and applied the OT II test director's immediacy criterion, I found that the tank's more realistically assessed MMBF had only improved from 34 to 43 miles.

In a report on testing of the M-1 released in January 1982, after I had done my own investigation of OT III results, the General Accounting Office levels the same charge against Army grading of the M-1:

…the Army's statistics mask the fact that the M1 sustained many component and part failures that did not figure in the Army's scoring.…However, statistics developed by the Army which measured mean miles traveled between what the Army terms "essential maintenance"…showed the tanks traveling 48 mean miles at Fort Knox [OT III] and 43 mean miles at Aberdeen [DT III] between essential maintenance demands.…These scores, however, did not figure in the official calculations.

As the GAO concluded:

This [the Army's actual] scoring methodology may be appropriate for measuring whether or not the contractor has met hardware design requirements. In our opinion, it does not realistically assess the tank's reliability or maintainability in the hands of soldiers.

TESTING BIAS Helping new weapons to make the grade by inflating test scores is one reason ineffective weapons make their way into soldiers' hands. My investigations have led me to believe that inadequate testing—testing that is biased in favor of the new weapons—is another key factor.

For example, operational testing is supposed to be the one way to make sure an unrealistic and inoperable weapon system does not reach the battlefield. To accomplish this, it is vital that the weapon be maintained and operated by the same average personnel and soldiers who will take the weapon into battle. Conversely, "babying" their exotic weapons through operational testing is another way the armed services can cover up battlefield weaknesses.

Maj. Gen. Richard Lawrence was responsible for the last phase of the M-1's OT III testing at Fort Hood, Texas. In March 1981 he told the House Armed Services Committee that "crews and unit mechanics are supporting the system as they would in combat, and they are doing it exceptionally well."

While this operational testing at Fort Hood was in train, I was invited by Sen. Ted Stevens (R–Alaska), chairman of the Defense Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee, to accompany him to Texas to review the M-1's performance. Our entourage included three senators, four Senate staff members, and myself. Instead of just watching the M-1 perform, we all had a chance to drive the standard M-60A1 tank as well as the M-1 tank, compare the gun stations of the two, and fire the M-1's main gun.

Although this public relations show was carefully staged, I did manage to talk to two tank commanders as we drove the tank. One of them asked where I had gone to college and surprised me by bragging about having graduated from an Ivy League school. Later, the other tank commander also told me that he had graduated from a large eastern university. These are hardly typical of Army tank commanders in the field, particularly since four of the five commanders in every tank platoon are supposed to be sergeants, not officers.

Later in the tour of the M-1 facilities, we were taken to the maintenance depot. Although several of the mechanics were quite young, I was struck by the age of the man who showed us how the Army tests the tank's electronic components. He was easily over 45 years of age and not in military uniform. Although I could not tell whether he was a Chrysler contract employee (General Lawrence insisted no contractor personnel were involved at direct support levels), he certainly was not the type of man one would expect out in the field in a wartime situation.

It would not be the first time overly qualified operators and maintenance crews were used in operational testing of new weapons. The General Accounting Office (GAO) has caught the Air Force doing it, too. In a June 1978 report to Congress, the GAO charged that

Air Force systems are not always operated and maintained during IOT&E [initial operational test and evaluation] by personnel with qualifications similar to those who would operate and maintain the systems after they are deployed. In many cases, contractor personnel perform much of the required maintenance.

Clearly above average Strategic Air Command pilots (graduates of test pilot school) were used during the B-1 test program. Pilots used for the A-10 test program were considered to be more qualified than the average Tactical Air Command pilot.…

Service maintenance personnel…were generally very high caliber with considerable experience working in their specialty area. They were usually much more highly qualified than personnel who will maintain the system after it is deployed.

The GAO concluded that, because of these and other testing deficiencies, "operational test results might not adequately reflect the performance, maintainability, and readiness of the systems in a realistic operational environment."

During Operational Test I (OT I) of the M-1 tank, the Army did do some testing that would be useful in seeing whether it would be more reliable on the battlefield than the standard M-60A1—they tested the tanks side-by-side. This is perhaps one of the best ways to find out whether a new system is worth buying or whether you would be better off modifying the old system.

The only problem is that the Army did not continue side-by-side testing throughout the development of the tank program. The following numbers may tell you why. In OT I at Fort Bliss, Texas, during 1977, driving over the same roads and using the same scoring conference measuring "system reliability," the M-60A1 went 493 mean miles between failures (MMBF) compared to 77 MMBF for the M-1. The Army's discontinuation of comparative testing again skewed the results in favor of the new weapon.

A few years later the Army's Logistics Evaluation Agency looked back through M-60A2 testing records, to see how the M-1's performance was stacking up. As noted in the 1979 logistics report, which I obtained by a Freedom of Information Act request:

A current comparison shows the M-60A2 tank was tested (engineering test/service test (ET/ST)) for a total of 26,667 miles and 622 performance maintenance reports were written. At approximately the equivalent XM1 test mileage (21,423), 1,752 performance reports have been submitted or about 3½ times the M60A2 incidents. [Emphasis added]

To place this in perspective, the M-60A2 was by far the most complex model of the M-60 series but significantly less "advanced" than the M-1. It has been widely recognized as a disastrous failure, so disastrous that all of the Army's 750 M-60A2s have been recalled from Europe. Despite the fact that the M-1 needed maintenance 3.5 times as often as the unacceptable M-60A2, the Army continued to push the M-1 tank program forward with unrealistic optimism and continued to praise the tank at every milestone and every attempted congressional review.

REPORT CARD MANEUVERS How much of the bad news discovered during operational testing reaches Pentagon decisionmakers and Congress? It is very hard to find out how much is transmitted during the closed-door meetings of the Pentagon's Defense System Acquisition Review Council that reviews each service's milestone decisions. But it is not hard to see that the promoters of the weapon system—the program manager, the research and development factions, and even the services themselves—are constantly trying to turn in to Congress glowing report cards that obscure bad marks in "battlefield" testing.

I have observed first-hand the elaborate effort the Army has made to minimize glaring faults of the M-1. Important shortcomings of the tank were not reaching Congress through hearing testimony or through the congressional staffs and especially not during congressional tours to review the weapon system.

One of the standard reporting-to-Congress techniques was demonstrated during hearings before the House Armed Services Committee on March 18, 1981. Maj. Gen. Duard Ball, program manager for the M-1 tank, told the committee that the power-train durability number had reached 30 percent—even though it had recently slipped from 22 percent to 19 percent, as Maj. Gen. Louis Wagner, commanding general of the US Army Armor Center at Fort Knox, had conceded to the committee earlier the same day.

While General Wagner was talking about the durability figure in operational testing, General Ball was using a figure that combined operational and developmental testing—although he didn't mention that to the committee. Since developmental testing is done by scientists in ideal conditions, the numbers from developmental testing are usually higher. They are often combined with operational testing results to pull up bad "battlefield" scores.

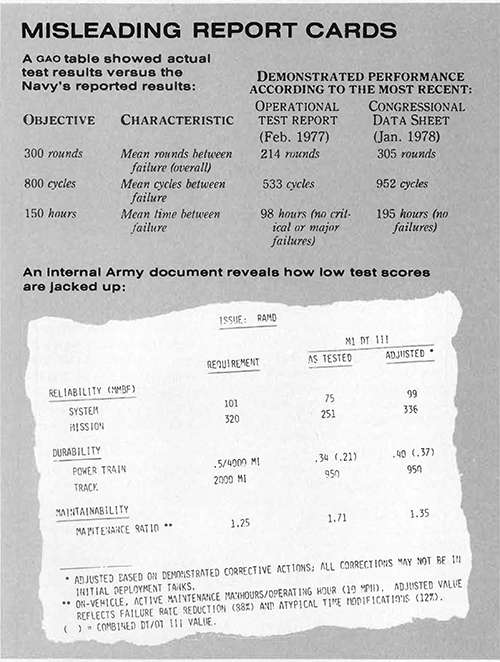

The General Accounting Office (GAO) has caught the Navy glossing over weapons problems in the same way. In a 1979 report to Congress, "Need for More Accurate Weapon System Test Results to Be Reported to the Congress," the GAO found that on a Congressional Data Sheet (a congressionally mandated report card to Congress) for the Major Caliber Lightweight Gun System, the Navy had also combined developmental testing and operational testing—and had put the combined results under the heading "operational testing" with no qualifying statements. The GAO showed with a chart (see box, p. 25) how misleading type of reporting is to members of Congress trying to decide whether to vote to buy the weapon. In the same report, the GAO revealed that misleading report cards had been sent to Congress for eight other Navy or Air Force weapon systems.

On November 5, 1981, Gen. John W. Vessey, vice-chief of staff of the Army, gave the House Armed Services Committee the final Army picture of the tank's RAM-D testing just after the M-1's full-production decision. Although he told the committee that the numbers he presented were based on combined operational and developmental test scores, he did not give any hint of the relative contribution of each.

Nor did Vessey mention that the developmental scores were not actual test results but "adjusted" results. The chart on page 25, reproduced from a summer 1981 internal but unclassified Army briefing that was leaked to me, reveals how important this adjustment was in helping the Army "meet" its RAM-D requirements. The creative "adjustment" referred to is to assume away any failure for which some engineer has subsequently proposed a fix, whether or not the fix has been installed.

Even after adjustments for such fixes, the M-1's crucial power-train durability requirement had still not been met. Although General Vessey admitted this to the committee, he did not give any number. In the final phase of operational testing, it was 15 percent, compared to a 50 percent requirement.

In a 1980 report released to me in January 1982 after being sanitized (classified material removed), the General Accounting Office concluded that, even after 10 years of GAO prodding of the services and the Department of Defense to improve their reporting to Congress, major problems still remained. Among its findings:

Congressional testimony for 11 of 36 systems we received either (1) included misleading or inaccurate data or (2) in our opinion, could have been improved by including additional data.

Eight of 16 Navy and Air Force data sheets for fiscal year 1980 still omitted or misstated data identified during our previous review which, in our opinion, should have been reported.

Budget justification data, including RDT&E description summaries,…contained the following:

—Misleading or incomplete statements of system capability (three systems).

—Misleading, incomplete, or inaccurate data on planned tests, test results, or operational experience (seven systems).…

…we identified…incomplete, misleading, or inaccurate reporting for 20 of 27 systems included in our review which have SARs (System Acquisition Reviews).

THE M-1 ROLLS ON To illustrate the way weapons testing is so deformed that it cannot serve its purpose, I have taken you through only one aspect of the M-1 testing—RAM-D. Deficiencies in many other, equally important, areas have not been fixed and are following the tank into full production and delivery to Europe. I discovered several very serious defects that appeared at the end of the testing of the M-1 but did not come to the fore in congressional testimony and review.

All the way through the troubled evolution of the M-1 testing, the Army has touted its "fire-resistant" hydraulic fluid and its fire-suppression system to protect the soldier from fires inside the tank. This is an important concern considering that, according to a top Israeli tank commander in the 1973 Mideast war, 300 of the 800 Israeli tank crewmen killed in that conflict were burned to death by the flammable hydraulic fluid in their US-built M-60s.

On November 5, 1981, General Vessey told the House Armed Services Committee:

Crew survivability, appropriately allocated number one priority, has had the greatest effect on the design of the tank. The system combines armor of a special design, compartmented ammunition and fuel, flame resistant hydraulic fluid, and automatic fire detection and suppression, to provide unprecedented crew-protection. Effectiveness of these systems has been demonstrated conclusively through testing of both individual structures and a combat loaded tank against a variety of potential enemy munitions including small arms, large caliber tank and anti-tank munitions, and anti-tank mines. The results are impressive evidence of this tank's outstanding protection for its crew. [Emphasis added]

Shortly after this testimony, I obtained a copy of an anonymous maintenance cable sent from Fort Hood, Texas, to the M-1 tank command in Warren, Michigan. The cable, dated October 1981 (after OT III, the last operational testing) listed many maintenance problems, but one item caught my eye:

E. Hydraulic Fluid (FRH). The high pressure hose from the reservoir has failed twice causing severe fire damage to the tank. The FRH burn point is only 216 degrees F and flash point is 425 degrees F. Any conception that its use makes the Abrams tank fire proof is in error. A substitute more fire proof fluid should be used. As an interim solution, this hose should be shielded to divert any spray away from the hot engine.

Although the cable provided no further details about the two tank fires, the thought that these tanks did catch fire twice, with no one shooting at them, was very sobering.

The low burn and flash points of the hydraulic fluid is particularly disturbing because the exhaust from the M-1's unique turbine engine alone runs between 900 and 1,500 degrees F. There are other, less flammable, hydraulic fluids on the market. Commercial airliners use Skydrol, a much more flame-resistant hydraulic fluid.

A colleague of mine then pointed out that, since the tanks did receive severe fire damage, the automatic fire-suppression system must have failed. A few days later, our fears were confirmed. I obtained a copy of an Army Developmental Test III briefing, dating from the summer of 1981, that listed the fire-suppression system as a "critical hazard" for the M-1.

In December 1981 I asked Gen. Robert L. Kirwan, head of the Army's Operational Test and Evaluation Agency, whether he was satisfied that the M-1 had met its requirements enough to warrant full production. His reply:

The M-1 tank was one of the most tested developmental acquisitions within the U.S. Army. The OTEA conducted thorough operational tests of the M-1 tank, reported and evaluated those tests, and presented its findings and evaluations of those tests to the appropriate decision makers. I am satisfied that our testing of the M-1 tank was accomplished adequately, professionally, and credibly.

Congress has approved funds for fiscal year 1982 for the M-1 to go into full production, and the Department of Defense has given the M-1 its official blessing as the US main battle tank. M-1s are now being shipped off to Europe.

CAPTURED TESTERS Why doesn't someone do something about this? you may ask. They have tried. Since 1970 there has been an intense effort to get operational testing away from the promoters of the weapons—the research and development community in the services and the Pentagon—and into the hands of independent operational testers who would put the soldier above the politics of procuring weapons.

In 1970 a Blue Ribbon Defense Panel appointed by President Nixon, perhaps in reaction to weapons failures in Vietnam, studied several issues in defense procurement, including operational testing. The panel found, for the most part, that the Operational Test and Evaluation (OT&E) function of the services was not managing to weed out undesirable weapons.

The panel recommended sweeping reforms, including establishing an independent Operational Testing and Evaluation group in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) under civilian leadership and establishing a separate, independent Defense Test Agency. They also recommended that the OSD testing group, as well as the operational testing program in each service, have a substantial and separate budget from the R&D groups.

Under the Nixon administration, Undersecretary of Defense David Packard responded by setting up a testing group in OSD, but this group reported directly to the Pentagon's chief weapons developer and promoter, the Director of Defense Research and Engineering, who is responsible for all weapons R&D and procurement. Packard appointed a retired Army general, Gen. Alfred D. Starbird, to set up the organization. General Starbird had deep roots in the developer community: he had been program manager of the Army's Anti-Ballistic Missile System—a system plagued with problems that had been covered up in testing.

There is an ongoing debate in the Department of Defense (DOD) whether the service testing agencies and the OSD testing group are truly independent of the strong research and development community in DOD. I interviewed one person in the Pentagon who has been deeply involved in testing and prefers to remain anonymous for fear of his position. He claims that these procedural reforms are mere "window-dressing" and that the so-called independent testing agencies are still "captured" by the R&D factions in the Pentagon.

When I asked retired Adm. Isham W. Linder, the current director of DOD Test and Evaluation (the "independent" group set up during the Nixon administration), if his office is truly independent, he responded with an emphatic yes. He admitted that his funding comes from the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering but claimed this is only for convenience. He told me that he does consult with Dr. Richard DeLauer, the undersecretary of defense for Research and Engineering, but can go "straight to the Secretary of Defense" if he needs to. For the record: the DOD directory lists Admiral Linder as part of DeLauer's R&E department.

In Linder's office in the Pentagon, we talked about reporting systems and program managers who become overzealous "salesmen" for their weapons. He described the role of his office as one of "monitoring tests" and watching over the service's testing agencies. He is happy, he said, with the Navy's test agency, which has been in existence since the end of World War II, but noted that it took the other two services "a long time to accept the idea" of independent test agencies. He also expressed satisfaction with the Air Force test agency but confided that the Army's agency, OTEA, is "fighting for life" from an overbearing TRADOC, the Training and Doctrine Command for the Army.

I left the office feeling that Admiral Linder is confident of his agency and the service agencies' watch over our weapon systems. He certainly does not seem to be the sort of man who would allow flawed weapons onto the battlefield to threaten soldiers' lives.

And yet…one must look at the record during his "watch." As director of Defense Test and Evaluation since the spring of 1978, he has overseen the testing of the M-1 tank, the newest version of the Sparrow missile, and the Navy F-18 fighter—all of which have had major testing problems. We don't know whether Linder raised a fuss at closed-door Milestone reviews of these weapons, but the ultimate proof of his effectiveness is whether the testing he "monitors" stops weapons that will fail on the battlefield.

Maj. Gen. Robert Kirwan, director of the Army's Operational Test and Evaluation Agency, is adamant that his agency is independent and reports directly to the Army vice-chief of staff. "The OTEA zealously protects its independence so that its assessments remain unbiased,"he said in a letter to me. Yet Admiral Linder is worried that OTEA is being swallowed up by the Army developer, TRADOC.

BATTLING THE SYSTEM Most of the "mavericks" in the defense testing area prefer to remain anonymous because they are still reliant on the Pentagon. I did meet one, however, who pushes his independence about as far as he can and still remain in a position of power. He is Vice-Adm. Robert Monroe, currently the director of Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation for the Navy. He has only been in this position for a couple of years; before that he was the head of the Navy testing agency, OPTEVFOR (Operational Test and Evaluation Force).

After a few minutes into our first interview, it was apparent that Monroe, although he has been kicked upstairs, is still an operational tester at heart. He spoke in glowing terms of the importance of operational testing and how it must be separate from developmental testing. "I believe in these things," Monroe explained. "There is a constant fight to ensure that expediency doesn't take over and weaken the (weapons) system."

He outlined the dilemmas and pressures that face an operational tester under the current system. There is resistance to his recommendations by the program manager and the sponsors of each weapon. The program manager is "on occasion more success-oriented" and willing to "burn more bridges" and move ahead with a weapon that is not fully developed or tested. Decisionmakers want to keep moving ahead with a program so that the service's budget does not lose the dollars associated with it.

Monroe insisted, however, that the operational tester wins in this struggle and that the Navy test agency is independent and reports directly to the chief of Naval Services. The 1970 Blue Ribbon Defense Panel also reported that Navy operational testing was the "most logically organized." And DOD sources confirm that Navy testing is good but worry that the test results are often ignored by higher-level brass.

As commander of OPTEVFOR, Monroe did manage to stop the Major Caliber Lightweight Gun (the MK-71) and to delay production decisions on the Navy Harpoon missile and the newest model of the Sparrow missile, the AIM-7F. In our discussion, he went into great detail about stalling production of the Sparrow air-to-air missile because of reliability problems—extremely low mean flight hours between failure.

A DOD unclassified analysis of the Sparrow testing supports Vice-Admiral Monroe's claim of good testing:

Testing conducted during IOT&E revealed or verified design and performance problems requiring major modifications. Early identification of these problems permitted the Navy (and the Air Force) to develop employment doctrine and tactics to minimize missile shortcomings.…

Adequate testing also provided the Services and DOD decision-makers with sufficient information to affect their decisions to delay production.…

Yet the report also refers to the AIM-7F's "limited potential in the more demanding combat environment" and "the controversy surrounding the missile system itself." As the operational tester of the newest Sparrow, Monroe was able to hold out on the narrow reliability issue but was still unable to stop it because of its lack of effectiveness.

The Sparrow has been built in various forms since 1955. They were used in Vietnam and were one of the notable weapon disasters in that war. At $44,000 each (in 1968 dollars) they only killed the target, according to a recently declassified DOD study of Vietnam weapons failures, in 8 percent of the firing attempts. The testing of the new AIM-7F Sparrow was not done side-by-side the old Sparrow to see whether it improved on the major deficiencies of the old one. This new version is claimed to be more lethal, but this could only be established by extensive firings against multiple real aircraft targets. These extensive firings have not taken place. I have been told by several Pentagon sources that the missile, at $120,000 each, still is not a very effective weapon.

Even if Vice Admiral Monroe also fought against the missile because of its poor effectiveness as a weapon, he was fighting a Sparrow weapon "constituency" that had been growing since 1955. Faced with that type of opposition, he was lucky to be able to delay the Sparrow because of reliability problems.

During my second interview with Monroe, he emphasized that the Washington environment is not conducive to careful consideration of operational testing needs or results. He called Washington a "hyper-political town" where people take sides on weapon systems based on general liberal or conservative politics. He does not believe in the independence of the OSD testing agency and would like to get testing "out of Washington" and place more reliance on the operational testers in the field.

CAN WE WIN THIS WAR? In 1977 a group of concerned defense experts in the Pentagon and President Carter's transition team, dismayed at the existing testing structure, took advantage of a new-administration reorganization. They convinced then–Secretary of Defense Harold Brown that testing had to be pulled away from the influence of the R&D community in the Pentagon. Secretary Brown agreed to set up a new independent testing and evaluation office to, as he told Congress, separate "the analysis of operational test results from the personnel responsible for research and engineering, thereby providing me with completely independent evaluation." The plan called for splitting the testing in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, leaving developmental testing to the developers and operational testing to the new independent group.

The R&D community saw this attempt as a direct attack on their ability to move weapons through the system without criticism. The attempted "coup" only lasted a little over a year. The undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering at the time was William Perry. According to Rep. Les Aspin (D–Wis.), Perry had convinced Harold Brown to limit the staff of the new OT&E organization to 8 people instead of the recommended 22 and had made it impossible for the group to obtain a formal charter that would allow them to ensure adequate operational testing. They did find that several major weapons—the Pershing II missile, the Infrared Maverick missile, and the GBU-15 (a TV-guided missile)—had been prematurely pushed into the production stage despite serious failures during testing. But in October 1978 the independent OT&E office asked to be disbanded (a remarkable occurrence in any bureaucracy) because of the impossibility of carrying out its functions without an appropriate staff and charter.

Congressman Aspin learned about the death of the agency after he discovered that the telephone number had been changed. He objected to the demise of the office, but to no avail. When I interviewed him recently, he referred to the OT&E defeat as "an indication of lack of commitment to getting to the heart of the problems of military procurement."

So what is the solution to the inordinate power of R&D interests? How can we get effective and affordable weapons to the soldiers in the field?

Vice-Admiral Monroe's proposal to get testing out of Washington might work if all the operational testers were as hard-nosed as Monroe, if the test data were not laundered, and if decisionmakers would listen to the operational tester and make the hard decision to cancel a weapon that will not work. There are too many loopholes for the weapons promoters to slip through in Monroe's solution.

Kwai Chan, group director of the GAO's Institute for Program Evaluation, would like to see money appropriated for missions and have several types of weapons in each service compete for this mission budget. For example, we might have the mission of defeating an enemy tank, and the Air Force would compete with the Army to come up with the best solution. This could be a very productive idea if the services would cooperate and if the testing were honest.

Several sources inside the Pentagon still believe in the possibility of an independent testing agency. One of them believes such a group could be successful if given "young and tough guys" who had not been trained in the old bureaucratic system. With the Reagan administration's moves to "decentralize" DOD, however, turning over major decisionmaking to the services, it is unlikely that this is a viable option for some time.

It is patently clear that more governmental studies or investigations will not solve the problem. Additional paper reforms promise to be deformed by the bureaucracy to fit its need to survive and advance careers.

How can this overzealous, money-spending developer complex be reformed? As a defense "ombudsman," it has been very hard for me to understand why people in the bureaucracy are able to do such a basically evil thing as to send a soldier into battle with a weapon that they know will fail. Thomas Amlie, former director of the Navy Weapons Center at China Lake, who has been in the system over 20 years, shed light on the problem in a paper widely circulated in the defense community a few years ago:

The DOD has all the symptoms of being corrupt, incompetent and incestuous, and is so to an alarming degree. This is not because of some sinister plot.…Many of the players are aware that things are going badly and are unhappy because they do not have meaningful jobs where they can contribute. They are not, in the main, dishonest or incompetent, just caught in a very bad situation.…The bureaucrat soon learns that he who does nothing has a simple life and he who tries to do something gets in trouble. Even if the doer succeeds, he is seldom rewarded. All pressures are to maintain the status quo and not rock the boat because the Congress and Administration are willing to put up the money every year, independent of the results.…

The basic reason for the problem is incredibly simple and will be incomprehensible to one who has not spent time in the system: there is no profit and loss sheet. Thus, there is no competition or incentive to produce. The goal of every good bureaucrat is to get an exclusive franchise on whatever it is he is doing. If nobody else is doing it, no one can measure how well or poorly he is doing it.…The only requirements are to stay busy, generate paper and make no mistakes. The reader tempted to criticize this behavior is invited to first imagine himself in the situation, complete with a large mortgage and children in college.

So to make sure we deliver affordable and effective weapons to the battlefield, we must have good and independent operational testing. But in order to have this type of testing, we must dramatically change the way the Pentagon procures its weapons.

Some simple but major changes would be to set up a testing system in which the developer and promoter of the weapon must turn the weapon over to the operational testers when the development tests end. Under the current system, these tests often run concurrently, OT and DT results are often muddled together, and there is no distinct decision point to go or not to go with the weapon. Another improvement would be to fire people who cover up, lie, or attempt to promote a weapon system that is not working. This would send messages throughout the bureaucracy that successful weapons, and only successful weapons, can get people promoted. It is also essential for Congress to insist that test results be reported under oath.

One of the most effective changes would be to refuse to fund any new weapon that costs three times as much as its predecessor, to set a reasonable budget limit for each new weapon and refuse to change it, and to reward innovative people who produce inexpensive and effective weapons—in other words, insert a profit and loss sheet in weapons procurement.

These changes would require a giant change in attitude on the part of the Pentagon, Congress, and the general public. One of the first steps toward this change is to support honest operational testing and a stronger role for test results in the decisionmaking process. This first step is necessary to begin to weed out the generation of ineffective weapons that are still being produced, "fixed," and handed over to our soldiers.

Can we do this as a nation without another war filled with weapons failure horror stories and countless numbers of our sons unnecessarily lost?

Dina Rasor is director of the Project on Military Procurement of the National Taxpayers Legal Fund in Washington, D.C. She has worked as a radio reporter and as an editorial assistant for ABC News.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Fighting With Failures."

Hide Comments (0)

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mute this user?

Ban this user?

Un-ban this user?

Nuke this user?

Un-nuke this user?

Flag this comment?

Un-flag this comment?