NASA Flimflams Congress

NASA's Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence: Congress nixed it, Proxmire fleeced it, but REASON's reporter discovered SETI still exists-it's just gone underground.

Is there intelligent life in outer space? Nobody knows, but some scientists think there might be. Back in 1959 physicists Giuseppe Cocconi and Philip Morrison first proposed that if extraterrestrial civilizations exist, they might communicate with one another across interstellar distances, using signals within a specific, narrow frequency range. Other papers followed, among them a now-classic 1966 book by I.S. Shlovskii and Carl Sagan, Intelligent Life in the Universe.

From speculation about how many suns might have planets, how many planets might have life, how many of those would harbor civilizations, and how those civilizations might communicate, space scientists soon progressed to the next step: a plan to collect data. The first such proposal was Project Cyclops, set forth in 1972 by B.M. Oliver and J. Billingham.

The basic idea was to have the National Aeronautics and Space Administration set up a network of computer- controlled radiotelescopes to listen for radio signals in what were estimated to be the most likely frequency bands. Before long, a general term for such plans came into use. As with all NASA projects, it quickly became known by its acronym, SETI—the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence.

In the mid-1970s a specific plan for a SETI program was developed within NASA, for inclusion in the agency's fiscal year 1979 budget. Distinguished scientists prepared a rationale, and the NASA budget went before Congress—only to have the SETI program be shot down in flames by the Senate Appropriations Committee. Even worse for SETI advocates, from a public relations point of view, was the reaction of the committee's chairman, Sen. William Proxmire. You guessed it: Proxmire awarded the SETI proposal his celebrated Golden Fleece award as the "biggest, most ironic, or most ridiculous example of wasteful spending for the month."

Proxmire recognized NASA's modest first-year request—about $3 million—as a foot in the door for far more ambitious expenditures in the years to come. Within a few years the spending for SETI was to have risen tenfold. By the 1990s, NASA hoped to have an Apollo-scale, open-ended SETI program under way.

Among the options under serious consideration were a gargantuan radio telescope in earth orbit and even a full-blown SETI colony on the far side of the moon. One of the reasons for advocating SETI set forth internally by NASA Office of Aeronautics and Space Technology was astonishingly frank: "no clear program office responsibility." It was the ultimate Washington nightmare: an office in search of a reason for existing.

When Congress explicitly refused to give NASA a SETI program, the matter seemed to end. NASA officials publicly maintain that no SETI activities continue at all today, except perhaps for a very few low-level investigations that are not part of any organized plan. In my first inquiries to NASA I was told outright that no SETI program exists, and REASON editors checking up on my story were told the same things (see box, p. 32).

IN SEARCH OF SETI It is common knowledge in the scientific community, however, that this is not true, and the zeal shown by NASA in keeping the wraps on its SETI activities made me especially anxious to dig deeper into the matter. I had soon obtained enough specifics from private sources to use the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) to obtain from NASA documents showing that, despite the refusal of Congress to appropriate funds for it, NASA's SETI program continues almost as if nothing had happened.

Through unofficial channels I learned that my FOIA requests had generated anxiety almost bordering on panic among SETI officials. One source said that people in the SETI office "ran for cover" when the request was presented. At first I received only nominal compliance with my requests, but after several iterations the full outline of the new, unannounced SETI program was documented. The program is a joint effort between NASA Ames Research Center at Moffett Field (Mountain View, California) and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL, Pasadena), with the program being managed by Ames. JPL is spending $500,000 in fiscal year '81 alone, with the total budget estimated at about $1 million. Funding for FY '82, not yet secured, is requested as $3.5 million, a sum equivalent to that requested for the "above ground" SETI program that was axed by Proxmire's committee.

How has NASA effectively circumvented both the Congress and the Golden Fleece problem? Its strategem is amazingly simple: the term "SETI" does not appear as a line item in the present NASA budget. Buried deep within the budget for NASA's Department of Life Sciences, however, a small appropriation for "exobiology" found its way through Congress where "SETI" had failed. SETI is indeed within NASA, but is simply not "called out" as a separate item. Congressional overseers of the NASA budget, whom I initially contacted for information, were unaware that any SETI program even existed.

A 1980 technical paper which I obtained from NASA via FOIA explains:

During the late 1970s, intensive effort was undertaken at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and Ames Research Center (ARC) to obtain the initiation of a formal SETI ("Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence") Program under NASA sponsorship. Starting in Fiscal (FY) 1980, such a program has come into existence. The NASA SETI Program is a Research and Development effort with primary thrust to search the microwave region of the spectrum for signals of extraterrestrial intelligent origin.

The program will utilize custom SETI radio equipment on existing radio telescopes.

Since at least 1975, Ames and JPL had been quarreling over the SETI approach to be used. Ames has long favored a "targeted search," where objects of potential interest are identified in advance and carefully scrutinized. JPL has consistently lobbied for a "sky survey,"in which no effort is made to prejudge where intelligent signals are to be found, searching the entire sky for possible signals of intelligent origin.

TWO-PRONGED COMPROMISE The NASA SETI Program represents a compromise, adopting both approaches in a "two-pronged search strategy." The targeted survey will examine all attractive stellar candidates within about 75 light years of the earth, in the radio band from about 1 to 3 Gigahertz (which includes the well-known 21-centimeter hydrogen line, as well as all of the band that Carl Sagan calls the "water hole," prime SETI territory). The sky survey will examine all directions in space in the band from about 1 to 10 Ghz. Because of the vastly greater area and bandwidth to be scrutinized, however, the sensitivity of the sky survey is only 1/1000 as great as the more limited targeted search.

The heart of the new program is to be a custom-designed Multi-Channel Spectral Analyzer (MCSA), currently under development. It is expected that any signals of intelligent origin will be of extremely narrow bandwidth, unlike natural sources that radiate over broad portions of the radio spectrum. A narrow-band signal will stand out more distinctly than a broadband signal of equal power output, but it is correspondingly more difficult to locate because one must hit the correct wavelength precisely.

For this reason the MCSA's design is very different from that of conventional radio astronomy equipment. Conventional equipment typically examines something on the order of 1,000 separate radio channels, each with a bandwidth of a few thousand hertz. The SETI MCSA, looking for signals of intelligent origin, will be able to examine some 8 million separate channels simultaneously, each with a bandwidth as narrow as one hertz.

There is no known natural source of radio signals of such narrow bandwidth and no reason to suspect that any such signals exist. While it is true that conventional radio astronomers will no doubt show at least some interest in the new equipment, one of the requirements of the SETI program is that "non-SETI telescope operations will be on a noninterference basis with the SETI system configuration."

HIDDEN COSTS According to NASA's official August 15, 1980, SETI Program Plan, the program's cost is currently projected as follows:

FY' 80 - $0.5 M

FY '81 - $1.0 M

FY '82 - $3.5 M

FY '83 - $6.0 M

FY '84 - $7.8 M

FY' 85 - $8.5 M

FY '86 - $9.2 M

FY '87 - $6.4 M

FY '88 - $4.3 M

FY '89 - $3.7 M

Total: $50.9 M over 10 years

This includes what NASA subtly terms a "program funding wedge," beginning in FY '87, "to pursue other search approaches that have not as yet been proposed or perhaps even formulated.…revised versions of the Program Plan will present increasingly concrete applications of the funding wedge." Discounting inflation, this is only slightly less expensive than the $60 million "above ground"program being drawn up by NASA in 1976 but axed by Congress. The present SETI Program Plan mentions none of the multibillion dollar programs under serious consideration earlier, such as the gargantuan Project Cyclops or massive radio telescopes in space.

According to the SETI Program Plan, "A 'Space Science Notice' will be issued by the NASA Headquarters SETI Program Office in FY '81, in the form of a 'Dear Colleague' letter. Its purpose will be to inform the scientific community of the nature and existence of the SETI Program, and to apprise them of the continuing opportunity to submit unsolicited proposals for participation." No mention is made of any plan to announce the existence of the program to the public, however.

In fact, quite the opposite appears to be the case—as noted earlier, NASA has resisted my every attempt to learn about its SETI program. My first FOIA request to NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C., brought only nominal compliance, and I received only three documents, which were already on public record and all of which predate the current SETI program. This was alleged to represent the sum total of all SETI documents at NASA headquarters from January 1, 1978, to the present! My second FOIA request to NASA headquarters had produced absolutely no response after more than 90 days, in apparent violation of the Freedom of Information Act.

NASA JPL released certain technical papers describing the SETI program but refused my request to see technical documentation on the SETI radio receiver on the grounds that "it is strictly in a research and development phase." I am not aware of any such provision in the Freedom of Information Act concerning unclassified civilian government papers. NASA-Ames at first objected that the sheer volume of SETI material made it impossible to comply with my request (a strange response concerning a nonexistent program!), but after clarification of my request Ames willingly provided a copy of the NASA SETI Program Plan. Both JPL and Ames were specifically asked to provide a detailed breakdown of their current SETI budgets; neither one sent any budget documents. However, since some budget information is contained in the SETI Program Plan, Ames appears to be in substantial compliance with my FOIA request.

A QUESTION OF SECRECY It is not my intention to pass judgment on the scientific merit of SETI nor on the, technical approaches to the problem devised by NASA. Considerable controversy exists within the scientific community on both questions, and I am not qualified to evaluate the merit of each of the positions. It does appear to me that the majority consensus in the scientific community is at least moderately pro-SETl and that NASA's proposed approach can be defended as technically sound. However, it is most unsettling that, having had its above-ground SETI proposal explicitly refused by Congress, NASA has simply proceeded to implement a nearly identical program in a clandestine manner. If the SETI program merits serious scientific consideration, it should be openly proposed and discussed in the same manner as any other scientific program seeking government support. If it cannot pass public scrutiny, it should not be funded.

Robert Sheaffer is a software specialist currently working in California's Silicon Valley. He is a frequent writer on popular scientific subjects and is the author of The UFO Verdict, recently published by Prometheus Books. This article is a project of the Reason Foundation's Investigative Journalism Fund.

THE TRUTH WILL OUT

We first received an article from Bob Sheaffer uncovering NASA's SETI program back in August 1980. The source for most of the story was his contacts within the scientific community and a person on Senator Proxmire's staff. It looked like a good article, so we began the fact-checking process.

When I called that Proxmire staff member, however, to confirm some figures and update others, he replied that NASA had no SETI program! I suggested that it might be going on even without being a line item in the NASA budget, but he insisted that NASA did not have a SETI program, line item or no.

My next move was to contact NASA directly. I called the person who heads up the Exobiology Division, told him we were looking into various space research efforts, and asked him what Exobiology was doing. He rattled off a list of concerns, none of them sounding like SETI. Was there any program to look for intelligent signals from space, I asked? No, he replied. Ames and JPL were doing a little work on how it would be done if it were to be done, he admitted. But there was "no SETI project."

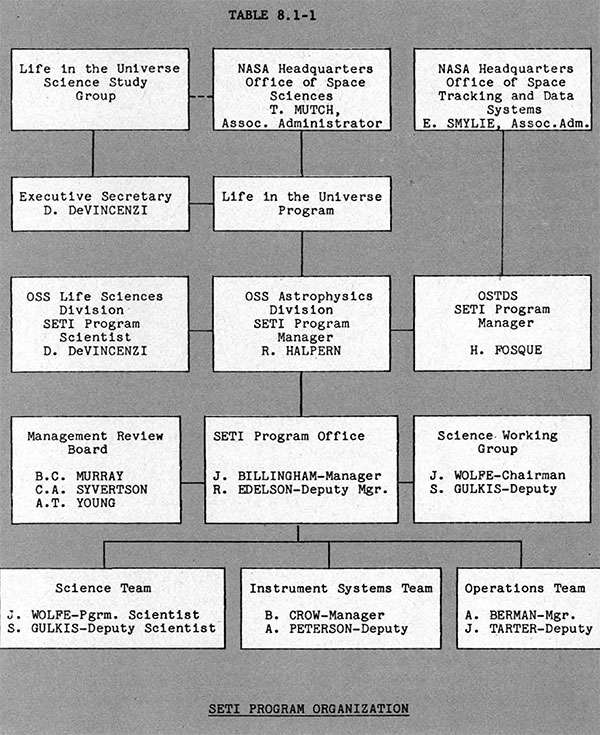

The name of the man I spoke with is Donald DeVincenzi, who shows up as "SETI Program Scientist" on an organization chart (right) found in NASA'S SETI Program Plan, which is dated August 15, 1980! That Plan was obtained only after we had sent Mr. Sheaffer back to the drawing board and he resorted to FOIA requests. Evidently, NASA would rather Congress and the public didn't know about SETI.

—Marty Zupan

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "NASA Flimflams Congress."

Show Comments (0)