Kept Critics

Did you know that your tax dollars are funding lobbyists for increased government regulation?

During the past 3 years the Federal Trade Commission has been doling out hundreds of thousands of dollars to various self-proclaimed public interest groups who then appear before the FTC Commissioners and commend them and their latest regulatory scheme as being a remarkable effort by the Commission to protect the public interest.

In reality, I have found there is far more personal interest and far less "public interest" in the administration of this program than is permissible under the statutes that control the FTC.…

—Sen. Alan Simpson (R-Wyo.),

Congressional Record, Feb. 7, 1980

Since the Federal Trade Commission was established in 1914, one of its primary responsibilities has been to investigate complaints involving allegedly fraudulent or deceptive business practices. For the first 60 years of its life, the FTC handled such matters on a case-by-case basis. Standard agency practice was to investigate a complaint against a specific business firm and, if warranted by the facts, take action against the offending firm.

Often the action took the form of a directive to the firm not to engage in the questionable business practices in its future business dealings. That is, the FTC functioned essentially as a police force pursuing individual wrongdoers and not as a quasi-legislative body issuing rules and regulations requiring compliance from all the businesses within an industry, whether or not they had ever engaged in questionable practices.

All this changed dramatically a few years ago with the enactment of the Federal Trade Commission Improvements Act of 1975, more commonly known as the Magnuson-Moss Act. Now the FTC can and does issue sweeping rules and regulations that apply industrywide and not just to specific firms engaged in "unfair or deceptive" practices. And what is an unfair practice? Under Magnuson-Moss, it is whatever the FTC finds or decides is unfair practice. Unfair practice is in the eye of the beholder.

Prior to Magnuson-Moss, the FTC had to show that the questionable practices it was investigating were actually "in commerce," or being done. Magnuson-Moss, however, allows the FTC to act if it thinks some business practices would "affect commerce." That opened up a whole new ball game. As FTC Commissioner Paul Rand Dixon put it, "There isn't anything you can do in the United States today that doesn't affect commerce, so we have been moved right down to every act in every state in every city."

Tacked onto this awesome grant of authority in 1975 was an innocent-sounding little amendment—the public participation amendment. Like the proverbial road to hell, it was paved with good intentions. The amendment authorized the FTC to "provide compensation for reasonable attorney's fees, expert witness fees, and other costs of participating" in the FTC's trade regulation rulemaking proceedings. The rationale: to open up FTC rulemaking to the public by reimbursing the expenses of groups that otherwise could not afford to participate.

The legislative history of the public participation provision—often called "intervenor funding"—illustrates how a lot of laws end up on the books. The amendment was added to the bill in the House-Senate conference committee. As a result, there were no hearings on the matter and no floor debates in either house. It was simply inserted into the conference report and became law when Congress passed and President Ford signed the act in 1975.

DISCRETIONARY FUNDING

Who gets to take part in FTC proceedings under this program? The exact language of the intervenor funding amendment gives the FTC a good deal of discretion in administering the program. The compensation provision states:

The Commission may, pursuant to rules prescribed by it, provide compensation for reasonable attorney's fees, expert witness fees, and other costs of participating in a rulemaking proceeding under this section to any person (A) who has, or represents, an interest (i) which would not otherwise be adequately represented in such proceeding, and (ii) representation of which is necessary for a fair determination of the rulemaking proceeding taken as a whole, and (B) who is unable effectively to participate in such proceeding because such person cannot afford to pay costs of making oral presentations, conducting cross-examination, and making rebuttal submissions in such proceedings.

With this wording, Congress granted the FTC considerable freedom to choose those on whom to bestow its largess. Naturally, the temptation looms large to parcel out intervenor funds to favored groups and individuals.

Would the FTC succumb to the danger warned of by John W. Gardner, former head of Common Cause? "Public participation proposes direct assistance," noted Gardner. "If the concept of conflict-of-interest means anything, then there is danger in potential critics of an agency being financed by the very agency they criticize. We could easily create a class of kept critics, and damage the future of an independent public interest movement."

Like Adam in the Garden of Eden, the agency has yielded to temptation. The history of the FTC's intervenor funding program—which has so far handed out nearly $2 million—is one of helping its friends and ignoring its adversaries. The result has been an almost total anti-business, pro-regulation bias in the allocation of what are, after all, taxpayers' funds.

In testimony before Congress in 1979, it was brought out that supporters of more regulation of business received 95 percent of the intervenor funds distributed by the FTC between November 1978 and May 1979. And in seven major trade regulation rule proceedings during that time, the commission funded only advocates of the proposed rule. The subjects of those proceedings and the grants involved were:

• children's advertising (kid/vid)—18 grants totaling over $133,000, including more than $32,000 to the group that originally petitioned the FTC to initiate the rulemaking (Action for Children's Television/Center for Science in the Public Interest);

• used cars—two grants totaling over $17,000;

• food advertising—one grant, over $3,000;

• over-the-counter drugs—two grants, over $7,500;

• antacids—four grants, over $26,000;

• insulation—five grants, over $14,800;

• funerals—eight grants, over $18,500.

When it comes to receiving FTC money, it seems that friends make out a lot better than enemies.

MUTUAL BENEFITS

The FTC's behavior is not that difficult to understand, of course. Despite what many people think, bureaucrats are human beings, so they generally make decisions based on what will benefit them the most. In this respect they are no different from ordinary consumers and business people.

Like those who toil in the private sector, bureaucrats are interested primarily in enhancing their salaries, working conditions, power over others, reputations, and prestige. Thus, they can be expected to be keenly interested in possibilities for action that increase their chances for promotion, raises, and growing influence.

Naturally, when the passage of Magnuson-Moss expanded the jurisdictional base of the FTC's power, the bureaucrats were not hesitant to move into the new territory. Adding to the momentum was the Carter administration's infusion of "consumer activists" into the upper levels of the bureaucracy. At the top, of course, was Michael Pertschuk, appointed FTC chairman in 1977. Pertschuk had been chief counsel to the Senate Commerce Committee when it was headed by Sen. Warren G. Magnuson, a favorite of the consumer movement. Pertschuk was the chief architect of many federal consumer laws, including the Magnuson-Moss Act.

Pertschuk's appointment delighted the consumer movement, for now they had one of theirs on the inside. The prospects seemed bright for advancing consumerism. The FTC and the consumer movement could work together for the mutual benefit of both parties. The agency would gain more bureaucratic turf by issuing new trade regulation rules under the expanded powers granted it by Magnuson-Moss. And the consumer groups would gain in prestige as regulations advocated by them were adopted by the FTC.

This symbiotic relationship was enhanced by the new ace up the FTC's sleeve—the public participation funding program. The FTC now had at its disposal a device whereby it could reward the very consumer groups that would be most likely to support its proposed new rules and regulations.

This is precisely what happened. The FTC has been very generous to a select few groups that share its penchant for more and more governmental regulation. The record shows that eight favorite groups received two-thirds of all public participation funds doled out by the FTC in 1979:

• Center for Public Representation—three grants for over $16,700 to testify in two proceedings, children's advertising (kid/vid) and thermal insulation;

• Consumers Union/Committee for Children's Television—three grants totaling over $39,000 on the kid/vid rule;

• Americans for Democratic Action—over $31,400 via five grants to support four rulemaking efforts (eyeglasses, over-the-counter drugs, health spas, and the funeral industry);

• Community Nutrition Institute—three grants for the kid/vid rule for a total of $33,368;

• National Consumers League—over $28,000 for two proceedings (care labeling and food advertising);

• Action for Children's Television/Center for Science in the Public Interest—over $32,700 from four grants for the kid/vid rule;

• Council on Children, Media, and Merchandising—over $31,500 from five grants for three rulemaking proceedings (antacids, food advertising, and kid/vid);

• Center for Auto Safety—three grants for over $18,000 to support two proposed rules (mobile homes and used cars).

PAYING FOR EXPERTISE?

Aside from the incestuousness of this relationship between the FTC and its paid supporters, there are other questionable features of the intervenor program. Was this small corps of ideological soul-mates even qualified to speak out on particular rules under consideration by the FTC?

Take, for example, the Council on Children, Media, and Merchandising, an organization that seemed to depend on the bounty of the FTC for its sustenance. It consisted of a single individual and had no dues-paying members. But from 1976 through the middle of May 1979, this "organization" received $185,839 in FTC intervenor funding to participate in rulemaking proceedings on antacids, food advertising, over-the-counter drugs, and children's TV advertising.

The Council's founder and principal member, Robert Choate, was astute enough to take advantage of the legal plum handed to him by the FTC. Choate understands how the game is played in Washington: "Washington is an organization town. The first question asked of one going to his or her government with other than a purely personal matter is 'who are you with?'" So Choate created an organization to be with, consisting of himself and 13 others listed on a letterhead—an "ad hoc group," he called it in a letter to the FTC.

So a clever Washington entrepreneur can create a paper organization. To qualify, however, for a large grant for extensive participation in FTC rulemaking proceedings, it would seem that an organization would have to have sufficient expertise. In fact, evidence shows that small groups that receive intervenor funding often end up farming out most of its participation functions to persons or organizations not eligible themselves for compensation—outside law firms, survey research companies, or individual experts-for-hire.

The Community Nutrition Institute, for example, received over $40,000 from the FTC to participate in the children's TV advertising proceedings. It was small—no paid members—and turned around and hired Opinion Research Corporation of New Jersey to conduct a personal opinion survey. The presiding officer in these FTC proceedings cited serious flaws and discrepancies in the survey, however. Likewise, the small San Francisco-based Safe Food Institute received over $12,000 to conduct a survey that was later found by the FTC not to be valid.

The problem with consumer groups as sources of expertise has been pointed out by Stephen Breyer in the Harvard Law Review. "Consumer groups, often in an adversary posture toward industry, tend to have the least experience of all," he noted. "Though they may appeal to competing elements within industry for help, they frequently are dependent upon the agency and outside experts for information."

And not just outside experts. According to C.C. Clinkscales, director of the National Alliance of Senior Citizens, proponents of the FTC's hearing aid rule were reduced to advertising for witnesses to testify before FTC hearings. In cities where the hearings were scheduled, they took out newspaper ads reading: "If you bought a hearing aid in the last 30 days, you were probably cheated. The U.S. Government wants to know about it." The National Council of Senior Citizens, sponsor of this ad, was given $46,734 in intervenor funding by the FTC.

MONIED INTERVENORS

Other groups receiving intervenor funds have been large organizations with substantial budgets. They could hardly be considered poor and in need of taxpayers' money to participate in the FTC's rulemaking proceedings.

Americans for Democratic Action, for example, has been awarded $177,000 in intervenor funding to participate in five separate proceedings. This group has a national membership in the neighborhood of 75,000 people and an annual budget exceeding $1.6 million.

The Sierra Club shared an award of $28,241 with four other environmental groups to participate in a rulemaking activity (the proceedings on thermal insulation). It has around 183,000 dues-paying members who come up with $25 a year. This gives the Sierra Club financial resources of at least $4.5 million annually.

The Environmental Defense Fund, one of the groups sharing the insulation grant with the Sierra Club, is able to maintain offices in Washington, D. C., New York City, Denver, and Berkeley, California. It takes a lot of money to keep four offices open in four major cities. Yet the FTC felt this organization needed taxpayers' funds to participate in its rulemaking process.

Consumers Union, another recipient of intervenor funding, has an operating budget of nearly $24 million. It has a staff of almost 400 and publishes the magazine Consumer Reports, with a circulation exceeding 2 million. This needy organization shared with another group $73,900 from the FTC just to participate in the children's advertising proceeding.

How can an organization with that amount of revenue be qualified to receive these funds? It is quite easy, Mark Silvergelb, director of CU's Washington office, told the Senate Subcommittee for Consumers in September 1979. "Consumers Union does not receive from its subscribers $23 million dollars primarily to support participation in either Federal Trade Commission rulemaking or any other forum." He went on to point out that Consumers Union's primary function is to publish its magazine, and it only devotes a small part of its operating budget to advocacy activities. "If you divert more than what is financially sound to nonrevenue producing activities [appearing before the FTC], you eventually reduce your ability to carry on both kinds of activities, revenue and nonrevenue producing, and you simply waste away the base of the organization's financial abilities."

Mr. Silvergelb is onto something, only he is probably not aware of its implications. If Consumers Union is concerned about diverting money into, as he calls them, "nonrevenue producing activities," what about the businesses that stand to be directly affected by the FTC's proposed rules? Won't they, out of necessity, maybe even to stay in business, have to divert money into nonrevenue producing activities—such as taking part in FTC rulemaking proceedings? If Mr. Silvergelb's group can't divert funds from Consumers Union without affecting its program, might not the businesses facing potentially devastating FTC regulation be up against the same problem?

WHAT THE BILL COMES TO

What has all this activity actually cost? During its first three years, the FTC intervenor funding program soaked up $1.8 million in taxpayers' money. The program virtually ground to a halt in mid-1979, as Congress kept the FTC on a short budgetary leash during nearly a year of grueling oversight hearings. The tough hearings eventually led to a rather mild FTC reform bill that slapped the agency's wrists for regulatory excess over such matters as the kid/vid rule but left its basic powers unscathed.

Since that time, however, few new trade regulation rules have reached the public participation stage. As a result, additional intervenor funding since mid-1979 has added up to only $187,000 so far, making the total expenditure since the program's inception just under $2 million.

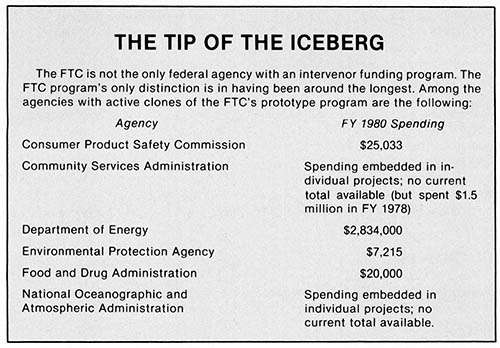

This figure may seem like a drop in the bucket when compared with the billions our government seems determined to spend on all sorts of schemes and programs. Yet, the $2 million is just one part of existing and envisioned intervenor funding spread throughout the government (see box, p. 41). In the 96th Congress alone, nearly 50 bills to establish intervenor programs were introduced. Although one of its champions—Sen. John Culver (D-Ia.)—was retired to private life last November by his constituents, the concept lives on. Its new hero is Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.), who has been active in trying to create a government-wide intervenor funding program since 1976.

In addition to the seemingly small amount spent so far on intervenor funding, its end product, rules regulating business, can have tremendous cost impact upon the consumers of this nation. Increased business costs resulting from the rules are passed on to the consumer in the form of higher prices for goods and services.

Since consumers are also taxpayers, they end up getting stuck with both tabs—the original (tax) cost of the governmental process and the increase in the costs of goods and services resulting from the action of the government. Joyce A. Legg, a taxpaying consumer from Virginia hit the nail squarely on the head when she told Rep. Herb Harris (D-Va.) in a letter that, "as a consumer, I have not been fleeced one tenth as much as I have as a taxpayer."

EXPENSIVE RULES

A good example of how FTC rules can raise costs to the consumer was its trade regulation rule "Labeling and Advertising of Home Insulation," the so-called R-value Rule announced in August 1979. The purpose of the rule was to mandate the disclosure of insulation capacity in labeling, advertising, and promoting home insulation products. The R-value is supposed to be a scientific measurement of thermal resistivity—the higher the R-value, the greater the insulation power.

There was one fly in the ointment, however. Testing to determine R- values is a complicated process overseen by the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) and the American Society of Testing and Materials (ASTM). The science of testing various thicknesses of the many and varied types of insulating products is still in its infancy. Just before promulgating its rule, the FTC switched from one R-value test to another and imposed new mandatory testing requirements. Until recently, meeting these changed requirements was beyond the capability of existing testing equipment and methods, a point made to the FTC by the NBS, the ASTM, the Department of Energy, and other experts in the field of thermal-insulation testing.

The FTC turned a deaf ear to these protests and proceeded with the rule. If it were to go into effect without proper equipment and standards, warned Stanley L. Matthews, president of the Mineral Insulation Manufacturers Association, it "will increase the cost to consumers of insulation by as much as $90 million."

Fortunately, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals put a hold on the FTC's rule; Congress reaffirmed that hold in its FTC reform bill. The National Bureau of Standards hopes to have standard calibrated equipment and samples available sometime this year.

In other recent action the FTC is proposing a set of rules requiring new warranties on the sale of mobile homes. "This is a classic case of overregulation," says Walter L. Benning, president of the Manufactured Housing Institute. "Every one of our homes must be inspected by agents from the Department of Housing and Urban Development before they can be sold. No other house in America must go through such rigorous inspection." The FTC estimates that its rules would increase the cost of a mobile home by only $100-$125, but Benning figures it would be more like $2,000 per home.

The cost to the consumer of the FTC's originally proposed used car rule requiring dealers to inspect 14 systems of the automobile and to disclose the results on a window sticker ("OK," "Not OK," or "We Don't Know") was pegged, during Senate testimony, at between $1 billion and $10 billion, depending on how the cost of the inspection and any subsequent repairs is calculated. Evidently, the cost seemed too high even to the FTC, for in April 1981 it approved only a twice watered-down rule requiring used car dealers to put in writing whatever warranties are offered and to disclose "major defects."

Attempts by the FTC to break up the cereal industry would, if successful, have serious economic consequences. According to Phil Leonard, United Rubber Workers Political Education Director, it "will mean over 2,600 jobs will be lost" in the cereal industry alone. In addition, Mr. Leonard pointed out, if the FTC proceeded with its proposal to ban children's advertising on TV, jobs in the toy industry would be lost.

THE COST OF THREATS

Mr. Leonard's latter fear is moot because in its 1980 FTC reform bill Congress forbade the FTC from issuing any ban on children's television advertising. But the mere announcement by the FTC that it is considering a rule can have detrimental effects upon the chosen industry.

The agency has proposed a rule that would allow health club members the right to cancel their membership contracts, for any reason (or no reason at all), at any time during the life of the contract. This rule would have disastrous effects upon the health spa industry because its ability to raise both long- and short-term capital depends upon pledging accounts receivable, in the form of membership contracts, to banks and other lenders for credit. The FTC's proposed rule would, in effect, make a health club contract a useless, nonbinding, one-party document that no lending institute would accept as collateral.

According to the September 1979 Senate testimony of Richard Wood, president of the Golden Life Physical Fitness Centers, when the FTC announced its proposed rules, "Abruptly, the financing for my Odessa [Texas] center was withdrawn, leaving me with no source of short-term working capital or expansion funds. Despite a delinquency rate of only two percent, I could not convince bankers or finance company executives to reinstate my financing. They were frightened by the severe nature of the FTC rule which calls for giving consumers the unilateral right to cancel their retail installment agreement with me at any time for any or no reason."

Wood was forced to ask prospective consumers to pay in advance for the entire term of their contracts. As a result, business at Wood's Odessa facility has dropped 50 percent and it has not shown a profit. The Texas gym is being carried by Wood's other clubs in New Mexico.

Dr. Reynold Sachs, a professor of managerial economics at American University in Washington, D.C., testified that "the proposed trade regulation rule would make it all but impossible for the typical health spa operator to obtain external debt financing…[and would] lead to an increase in the number and frequency of bankruptcies and insolvencies.…consumer prices would increase by an estimated 100 to 200 percent."

HITTING THE LITTLE GUYS

Other direct costs to business are more difficult to measure. For example, consider the cost involved in the sheer amount of paperwork involved in FTC rulemaking proceedings. The average record of a proceeding is 25,000 pages; some exceed 50,000 pages.

How can a businessman, especially a small businessman, wade through that morass of paperwork and still devote sufficient time to his business? Clearly, it is beyond the means of the average business owner. And although large corporations can hire teams of lawyers to do the job, such expenses are passed on to the consumer.

It is not the large corporation, however, that is the typical target of FTC activity. The FTC is a bureaucracy employing 700 lawyers that seems to thrive on hassling the small businessman. As Dr. F.M. Scherer, former director of the FTC's Bureau of Economics, told a 1976 hearing before the House Small Business Subcommittee: "What I have learned since joining the Commission staff is that many attorneys measure their own success in terms of the number of complaints brought and settlements won. In the absence of broader policy guidance, therefore, the typical attorney shies away from a complex, long, uncertain legal contest with well-represented giant corporations and tries to build up a portfolio emphasizing small, easy-to-win cases. The net result of these broad propensities is that it is the little guys, not the giants who dominate our manufacturing and trade industries, who typically get sued."

Among the indirect costs of FTC rulemaking is the time lost by businesses in trying to comprehend the proposed FTC action, fighting it, or both. Any time spent on these activities is time not spent on providing goods or services desired by consumers, which means higher prices for the ones that are provided.

The heavy-handed intrusion of the FTC into the affairs of business also generates a climate of fear. Zealous defenders of the regulatory agencies will applaud this, saying the businessman will be too scared to try any shady tactics. (This is a dubious assertion because anyone who is bent on fleecing consumers is not likely to be overly deterred, if at all, by some FTC regulation.) But the other side of the coin is that the climate of fear also makes entrepreneurs have second thoughts before developing and introducing new goods and services that may be better and cheaper than those currently on the market.

CURBING THE FTC

The FTC's use of public funds to hire advocates of its position on proposed industry-wide rules is a gross abuse of its powers and of the taxpayers' money. As Senator Simpson told his colleagues in 1979: "In a free society it is intolerable that the taxpayer should be required to finance private lobbying groups, who often take positions opposed by a vast majority of our citizens."

Unfortunately, Simpson's words had little effect upon his Senate colleagues last year when they passed their weak-kneed FTC reform bill. When they finally approved the agency's budget the intervenor funding program was continued, with but two restrictions: the amount that any one group can be awarded is now limited to $50,000, and 50 percent of the grant funding must now go to business interests.

The reform bill took several other steps to restrain the FTC, namely allowing new FTC regulations to be vetoed by a vote of both houses of Congress and restricting somewhat the proposed FTC regulations on children's TV advertising, voluntary codes and standards, trademarks, cooperatives, life insurance, and funeral homes. In other words, the big boys with the political clout won a reprieve from the FTC. But Congress left the small businessman still exposed to the agency's awesome powers.

The FTC intends to use that power. After the legislation was signed into law, Chairman Michael Pertschuk told the Associated Press, "We intend to go ahead with everything Congress hasn't specifically stopped us from going ahead with." In spite of the change of administrations, the FTC is still peopled by those who have admitted to carrying out a vendetta against whole industries. They are ready, willing, and able to dream up new rules to regulate business, as Pertschuk has admitted. They can still dole out money, although now on a reduced basis, to hire groups to speak for their proposed rules and regulations.

Last February the Reagan administration sent shock waves through the Federal Trade Commission. The Office of Management and Budget recommended that the FTC's current fiscal 1981 budget be cut by 13 percent and its 1982 budget by 24 percent. OMB also urged that the intervenor funding program be abolished.

The latter, however, is a creature of the Congress. Congress conceived intervenor funding, gave birth to it, annually nourishes it with taxpayers' funds, and regularly contemplates cloning it for other federal agencies. It is up to Congress, not the OMB, to get rid of the little monster it created.

The time is rapidly approaching when, according to former Atty. Gen. Griffin Bell, "if the Republic is to remain viable, we must find ways to curb, and then to reduce, this government by bureaucracy." A good place to start would be to abolish the practice of intervenor funding.

Morgan Norval is a Washington-based freelance writer. This article was sponsored by the Sabre Foundation Journalism Fund. Copyright © 1981 by the Sabre Foundation.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Kept Critics."

Show Comments (0)