Socialism…on the Street Where You Live

All across the country, the new "progressives" are taking steps to capture the cities' wealth

Last November's conservative double-whammy—the defeat of five liberal senators and the victory of Ronald Reagan—has given many opponents of the welfare state a sense of euphoria. The tide has at last been turned, they think; the social and economic devastation wrought by 20 years of liberalism is now at an end, history is on their side, and from here on out conservatives are firmly in the driver's seat.

In fact, the new reality is somewhat more complicated. Although the right has ascended to power on a national level, at the same time, in communities like Cambridge and Ann Arbor, Berkeley and Santa Monica, leftist coalitions are running sophisticated and effective campaigns for local public office, winning seats on rent boards, school boards, planning commissions, and city councils. Once in place, they make full use of generally unexercised powers of local government to redistribute wealth and reorder social priorities. Because they tie their programs to such real issues as housing, city planning, and energy use, they've been able to attract considerable support for a frankly socialistic agenda.

Not that they actually call it socialism anymore—that reminds people too much of politburos, Afghanistan, Cuban mercenaries, and Soviet tanks. Besides, socialism suggests a Marxist perspective, a tendency to see history in terms of class struggle, oppressed masses, and revolutionary proletariats—none of which has ever characterized the American experience. Instead, the more subtle leftists now refer to themselves as progressives; they engage in community organizing, not class struggle; and it isn't socialism they're striving for—it's "economic democracy."

Who Are These People?

(And What Do They Want?) Because the progressives aspire to mainstream political power, they take great pains to distinguish themselves from radicals of the late-'60s stripe. In those days, the radicals actually expected violent, apocalyptic revolution—guerrillas in the hills and tanks in the streets. Militancy was seen as a sign of sincerity. The political dialogue had moved so far left that mere socialists were considered reactionary, leaders of the Students for a Democratic Society declared themselves "revolutionary communists," and SDS's most militant faction, having broken away to form the Weather Underground, began blowing up buildings and also occasionally themselves.

The radical debacle ended in the early '70s. The tide of public opinion had turned against the war, but the left was no longer leading it. Instead, the same students who presumed to be the workers' vanguard into a revolutionary future had themselves been attacked by construction workers on New York City streets. Within a few years, the old radical left had virtually disappeared, its members estranged from politics entirely, opting instead for drugs, mysticism, and bean sprouts or, as one survivor put it, "spending a year putting a skylight in their kitchen."

As the progressives tell it, none of them was even speaking to radicals in 1969, and certainly they were never so out of touch with reality (except only once, and then just for a minute) as to believe that the country was on the edge of violent revolution. So although today's progressive leadership is older than the radical leadership of the late '60s, this isn't, they claim, simply a matter of its being 10 years later now and the radicals have all settled down and become respectable progressives. As SDS cofounder Richard Flacks explains it, "Those who believed in '69 or '70 that an apocalyptic revolution was imminent weren't able to make the change to mundane local politics." One notable exception, they say, is Tom Hayden, who now heads up the Campaign for Economic Democracy. Or as Hayden says, "Then is then and now is now."

Like radicals of the '60s, however, today's progressives tend overwhelmingly to come from comfortable urban, white, middle-class backgrounds. The familiar litany of their constituency is still the same—women, poor people, minorities, gays, and the working class. But the poor people they end up benefiting tend in many instances to be white college graduates (many with advanced degrees) in their middle and late 20s who are poor, if they are poor, because they have not chosen to take the $25,000 jobs waiting for them in business or industry. Much is made of minority representation in the progressive movement, but at a national conference of progressive activists and community organizers held last summer in Pittsburgh, blacks accounted for the merest sprinkling of the 650 registrants, and most of them were on speaker's panels. Finally, progressives constantly accentuate their ties to labor, but like radicals of a decade before who professed solidarity with the workers but tended to despise the silent majority—and especially those blue-collar workers in the construction trades, variously demeaned as "hardhats" in the North and "rednecks" in the South—the progressives of the '80s have failed to forge ties with any labor except public employee unions. "I'm saddened by the total fear in which people live of CED," says Sam Hurst, a communications specialist in Hayden's Campaign for Economic Democracy.

The most important difference between an '80s progressive and a '60s radical, perhaps, is that the progressive believes that the route to power in this country lies, not in some apocalyptic national convulsion, but in grassroots, door-to-door, block-by-block community organizing on specific issues. Unlike '60s radicals, many people in the progressive leadership ranks were active not only in the antiwar movement but also in civil rights and community organizing in the Saul Alinsky tradition. An unusual number tend to have advanced degrees in economics or sociology. Many teach school, work in social service agencies, or run programs of their own with foundation or government support.

Their outlook is fundamentally socialist, but it's not the ideological Marxism of the European intellectual variety. (Recently I was talking to a labor union attorney on the Santa Monica rent board who complained that someone had called him a Fabian socialist and he still hadn't found out what that is.) Most progressives don't believe in public ownership of the means of production, say prominent leftists like Lee Webb, so it's really not correct to describe them as socialists. And in fact, for leftists, progressives do seem unusually wary of centralized State control—understanding, perhaps, as radicals never did, that State ownership of the means of production in the Soviet Union has never been at all incompatible with, in the words of leftist writer David Horowitz, "oppression, pollution, imperialism, and exploitation." So progressives like to stick by their distinction: what they want, they say—and this is the thrust of economic democracy—is public control of the means of production.

Lee Webb, director of the Conference on Alternative State and Local Policies, is probably one of the more archetypal '80s progressives. He dresses like a young Ivy League professor, exhibits a calm patrician air, and only occasionally falls into a patronizing tone (probably as a result of having answered similar uninspired questions a few hundred times before). By Webb's account, he had a relatively privileged upbringing, spending his adolescence in private schools, attending Harvard and Boston universities, earning a doctorate in economics, and taking off weekends to fight for civil rights, once being arrested for attempting to integrate a Baltimore cafeteria.

In 1963 he became national secretary of SDS. Under his leadership, membership mushroomed from 10 to 125 chapters within a single year. He later registered as a conscientious objector, worked for a year and a half for the National Council of Churches in Chicago, then became Washington editor of Ramparts. By 1966, SDS had already begun its long slide into revolutionary Marxism, and, in an internal political dispute, Webb was purged for bad politics. In disgust, he abandoned ideological politics for the next five years and instead moved to New England, where the issues, he says, were all concrete commonsense ones like culverts, potholes, and school bus routes.

In 1972 he worked for McGovern, was involved in a couple of governor's races over the next few years, and began to notice an interesting phenomenon—some of the same people who, like himself, had been active in leftist politics in the early '60s were now conducting successful campaigns for public office. Loni Hancock was a city councilwoman in Berkeley, California; Sam Brown, the state treasurer in Colorado. There was a comptroller in Houston, a mayor in Mississippi, and a county judge in Texas. If these people met and exchanged ideas, thought Webb, they might be able to help one another.

Webb had, several years earlier, been a student and then a research assistant at the Institute for Policy Studies, a left-wing think tank in Washington, D.C. Now he called upon the two cofounders, Marcus Raskin and Richard Barnet, for a $500 grant to travel around the country and bounce his idea off those leftists-turned-politicians. Webb visited Boston, Hartford, New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Berkeley, Denver, Minneapolis, Madison, and Chicago. Not long afterward, IPS put up $10,000 to launch the nonprofit, tax-exempt Conference on Alternative State and Local Public Policies (they later removed Public from their name).

Every year since 1975, the group has held a summer conference for local activists, community organizers, leftist intellectuals, and progressive state and local officials. It distributes a bimonthly newsletter and has published scores of books and pamphlets. In a conscious attempt to avoid the sectarian squabbles have wrecked so many leftist organizations in the past, the conference neither takes stands, elects officers, nor passes resolutions.

What it does try to do is spread the conviction that state and local government will be the major arena for progressive change in the '80s—it's been growing twice as fast as the federal government, they like to point out. The progressives already have dozens of grassroots organizations firmly in place around the country (see box, p. 34). And history, they believe, is solidly on their side.

State of the Nation

(A View from the Left) As the left sees it, what the people need but don't have is power. Why don't they have it? Because it is unfairly, unreasonably, and undemocratically concentrated in multinational corporations and the federal government. The left's goal is to eliminate these concentrations of power and instead spread it through all levels of society.

They do not, however, want this called socialism. In the words of Derek Shearer, a progressive economist, a lecturer at UCLA's School of Architecture and Urban Planning, and coauthor of Economic Democracy: The Challenge of the 1980s, socialism "has a bad name in America." People mistakenly identify it, in its mildest form, with the bureaucratic welfare state and, in the worst case, with "Russian totalitarianism"—"and no amount of political education or wishful thinking on the part of the left is going to change that in our lifetime." So Shearer recommends that the left avoid the language of alien ideologies. He himself claims credit for coining the term economic democracy, a phrase implying that democracy can be extrapolated in a simple, straightforward way from our familiar political democracy to the economic sphere and therefore that economic democracy, unlike socialism, is in no way strange or dangerous or at all unAmerican.

Consider, then, what economic democracy amounts to, by Shearer's account: Ownership of business enterprises would be "heterogeneous and diffused, with the government—state and local, as well as federal—unions, churches, pension funds, workers, community groups and private families all owning and running businesses." To create such an economy, there would have to be a "dramatic increase" in cooperatives (Shearer himself was appointed by President Carter to the National Consumer Cooperative Bank), community development corporations, worker-owned enterprises, and public enterprises to off-set present-day domination of the economy by multinational corporations." To bring about such changes, Shearer estimates that the left first needs to "collect" some 20 to 30 governors, an equal number of big-city mayors, 10 to 20 senators, perhaps 50 House members, the leaders of three or four national unions, and the support of a sympathetic president.

By necessity, the left is organizationally loose. It's not centered on a labor party. There isn't any correct line. But the goal is everywhere the same—learning how to win and use political power.

Despite the Reagan landslide, the left has high hopes for continued success throughout the '80s, which it sees as a time of profound change. Although conservative forces seem temporarily to be in the ascendancy, "the right," according to Steve Max, an instructor in community organizing at Chicago's Midwest Academy, "cannot for long conceal the fact that it is the organizational vehicle of the corporate program." And with every passing day, more working people will realize that the "program of the corporate right won't solve the country's problems."

As people become disenchanted with the right, however, there won't be the siren call of the liberal center to bury, betray, and otherwise co-opt the leftist alternative, for the centrist alliance that has dominated national politics in this country since the end of the Second World War is fast falling apart. "The basic assumptions on which it was based no longer apply," says Institute for Policy Studies director Robert Borosage. As the left sees it, the faltering economy has pulled all the props out from under the liberal platform. For too long liberals identified themselves with a growing bureaucracy fueled by an ever-expanding federal budget as the best way of helping poor people. In an era of austerity, the liberals have been stripped of their program. They're confused and demoralized, their credibility next to zero.

Progressives, on the other hand, says Lee Webb, because they are concerned—as liberals never were—with the "structure" of the economy and government, are able to offer a program that increases services and benefits to citizens without increasing the budgets of local governments. He offers rent control as an example. "It's a direct way of benefiting tenants," he says, that doesn't require an increase in taxes.

It isn't necessary, says Steve Max, that the left go into great detail describing some ultimate society—"in fact, it's better that we don't." But the left could at least project an "interim vision" for the '80s and '90s of a society free of corporate domination, a vision that people will feel "is worth working and fighting for."

The Interim Vision

(The Wealth of Cities) A comprehensive strategy for achieving "community economic control" was set out a few years ago in a leftist treatise called The Cities' Wealth. Financed in part by the Institute for Policy Studies and published and distributed by the Conference on Alternative State and Local Policies, the book grew out of the first heady successes of progressive activists in Berkeley, California, in the early '70s. "We have compiled" this book, say its authors, "with the intention of sharing the Berkeley experience as widely and usefully as possible."

The premise of The Cities' Wealth is that the political power of city government can be used to control and reallocate wealth at the local level. And in this control, housing is presented as the key. Not only does housing account for the largest part of a community's wealth and a substantial part of household spending, but "housing can be controlled far more easily than other forms of wealth which are moveable and beyond the scope of legal regulation by the city." The ultimate goal, says The Cities' Wealth, is community ownership of all housing and real estate. As "interim steps" toward this goal, the book suggests tenant unions, rent control, "neighborhood preservation ordinances," city-subsidized rehabilitation of low-income housing, and strict enforcement of building codes—all effecting "the expropriation of income property values."

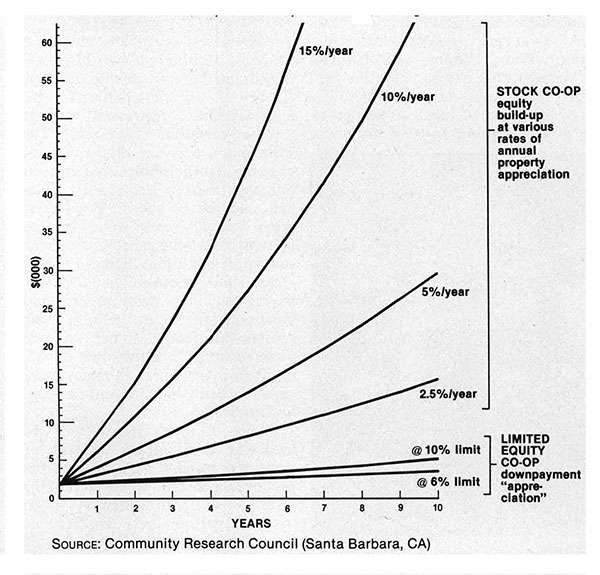

With rent control, for example, "a city may actually reduce the present value of a property. This is essentially community expropriation in favor of tenants." In fact, says The Cities' Wealth, if rent control is confiscatory ("stringent") enough, the housing market will collapse because "other private owners would be unlikely to buy the property in such an unfavorable climate." Then, unable to earn any profits and lacking other buyers, landlords will sell their property cheaply to the city or to the tenants themselves under the progressives' desired form of joint ownership—limited-equity co-ops, which are essentially condominium arrangements with controls on the resale price, the idea being that no one (not even ''downtrodden tenants") should profit from any appreciation in property value during the period of ownership (see graph, p. 27).

Another passage in The Cities' Wealth suggests using the city's police powers to "demand housing repairs of landlords without compensating them for the cost. If a landlord refuses, the city may make the desired improvements at public expense, place a lien on the property, and then sell the property, preferably to the tenants." More conventional housing regulatory powers, too—condemnation, downzoning, limits on condominium conversions—can be used to create "a climate for community ownership by acting to reduce the value of income property prior to community acquisition."

As the left tells it, such draconian measures are justified because of what The Cities' Wealth characterizes as the "abject failure" of the free market to provide adequate housing for low- and middle-income Americans at a price they can afford—not that the left blames the soaring costs of renting an apartment or buying a home on any shortage of housing. To a large extent, the left simply rejects the notion of supply and demand, arguing instead that the cost of housing has been driven up by rapacious speculators, those greasy guys in blue suits and black shoes who descend on a community unannounced, gorge themselves on frenzied real estate deals, and are out of town before dark, fat with their unearned profits. And the cause is pure greed ("the greedy raking off the needy," was the way I once heard a community organizer explain it to the Los Angeles City Council).

In the rhetoric of the left, some things are just too important to be left to the machinations of the so-called free market, and one of these is housing. Take the profit out of housing, and you'll solve the housing crisis overnight.

And so it goes with the rest of The Cities' Wealth agenda: structural changes, and not just reform, of every aspect of a city's economic and political life, including utilities ("a point of entry for broad public ownership of productive enterprises"), banking ("to control the wealth within municipal boundaries"), cable television, transportation, social services, insurance, ownership of commercial shops, elections, and taxation. It won't be easy, say the Berkeley activists in conclusion, but by gaining elected and appointed positions in city government, and using the existing powers of city government, the progressives can gradually implement more and more economic redistribution—or, as Derek Shearer reformulates it for the sensibilities of the mass market, "economic democracy."

Leftist Thought in Action

(The California Experience) With housing recognized as the key to a community's wealth, the left has been presented with a golden opportunity in California's housing crisis. They weren't the original cause of it, but by pointing constantly to the alleged failure of the free market, they have provided a rationale for restrictive land-use and rent control laws that only guaranteed that the housing industry would not be able to supply shelter at a cost most people could afford. The resulting shortage, in turn, became the justification for still greater governmental intervention, bureaucratic expansion, and public expenditures—the prime beneficiaries of which are the left, both in jobs for activists and the perceived legitimacy of their progressive program.

The roots of California's housing crisis go back 10, 12, and more years ago, to the time when people first began expressing their tentative misty yearnings for a better quality of life. Those desires were initially diffuse, confused, often clothed in the rhetoric of some other goal. But eventually a basic theme emerged: people felt besieged by heavy traffic, rampant growth, bad air, a ravaged coast, vanishing open space, and a tidal wave of immigrants. What they wanted was control, not chaos; order in their lives, not accelerating change. Many California cities responded with strict antigrowth ordinances. Among the strictest were those of Berkeley and Santa Monica.

With its tree-lined streets, Berkeley has always been one of the most desirable places to live in the entire San Francisco Bay Area. As pressures on the city's housing stock began to grow in the early '70s, increasing numbers of older buildings were being torn down and higher-density apartments put up in their place. Environmentalists saw this as the ticky-tackization of an entire community. Homeowners worried that a growing renter population would hurt their property values. And the left saw an opportunity to strike back at much-despised speculators and developers. The result was the Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance of 1973. Under its provisions, no new construction would be permitted without formal approval by neighborhood residents; there was a moratorium on demolitions; and 20 percent of any new building had to be set aside for low- and moderate-income families. This last requirement was a deliberate attempt to halt all new construction. As was pointed out in The Cities' Wealth, proponents "understood that no private, speculative developer would either desire to provide lower class housing, or be able to afford such inclusion without subsidies."

The results of the ordinance were predictable—neighborhoods placed a virtual freeze on new construction. Builders gave up on the city entirely. As demand for housing continued to rise, prices began to escalate. This set the stage for rent control (it had already been passed once in Berkeley in 1972, but in 1976 the courts set it aside for legal deficiencies). And in the wake of Proposition 13 in June 1978, when few if any landlords passed on to tenants the property tax savings that Jarvis had promised, rent control became inevitable.

Santa Monica's problems first began back in 1965, when construction of the Santa Monica Freeway was completed and downtown Los Angeles was now only 20 minutes away. No longer was Santa Monica an isolated beach community of blue-collar workers from the Douglas Aircraft plant. Young professionals flocked to the city to enjoy the perquisites of salt water and clean air. Over the next 10 years, 40 percent of the city's current housing stock was constructed. New apartment houses were going up on every block, prompting complaints from homeowners about traffic, high-rises, and the shrinking ocean view. There was too much growth, the argument went. Santa Monica was becoming another LA. If people had wanted to live in concrete canyons, they'd have stayed in New York.

By 1975 the city council had passed a series of antigrowth ordinances severely limiting the number of units builders could construct on a lot. Prior to 1975 it had been possible to build up to 16 apartments on a 50 x 150 foot lot; now, it was only seven. Apartment house construction staggered to a halt—the economics no longer penciled out. But this, of course, didn't stop the demand for housing. In the words of one landlord, "the $30 blue jean had arrived," and rents that had been "severely and artificially depressed for years by excessive new construction" finally began to rise. This produced a fearful reaction from older tenants, who descended on city hall en masse demanding rent control.

Sun, Surf, and Socialism

(Rent Control for Santa Monica) The left's account of how they won the Santa Monica rent wars has a certain dramatic, even mythic, quality. As they tell it, it was a battle of David and Goliath, oppressed tenants against corporate landlords. The speculators, they say, had run rampant in Santa Monica. Apartment buildings that in less chaotic times had sold for 10 and 12 times their gross annual rents were, in the months before the enactment of rent control, selling for as high as 18 times gross. They cite out-of-state investors buying buildings sight unseen and business magazines telling their readers that Santa Monica was one place where an investor could double his money in a year. Tenants were regularly being hit with rent raises as high as $150 a month.

Filling in their Goliath view of landlords is the left's account of apartment owners' panic at the prospect of rent control. In the six months prior to rent control, they say, 2,000 to 3,000 persons were displaced as apartments were converted to or replaced by condominiums. In the last six weeks, there were so many demolitions for condominium construction that parts of Santa Monica "looked like Vietnam," says Roger Thorton, spokesman for Santa Monicans for Renters Rights. "They were in such a hurry to tear these buildings down, because if it was torn down, you can't rent control rubble. And they were coming in with bulldozers and just leaving a pile of sticks and stones and bricks and wood."

Making the left's victory that much greater in their eyes was the fact that landlord/developer/realtor forces had vastly greater resources, outspending them ten-to-one, while the renters' rights coalition (tenants groups, senior citizen activists, and Tom Hayden's Campaign for Economic Democracy) relied on thousands of individual contributions, assorted fund-raising dances, auctions, and a $4-per-person spaghetti dinner featuring a screening of Grapes of Wrath and a personal appearance by Henry Fonda, who read selections from the book.

Although badly outspent, the left had "the people." "We went door to door," recounts Derek Shearer. A thousand persons volunteered. There were phone banks, mass mailings, and precinct walkings. "To me," says CED spokesman Denny Zane, "it was a classic case of popular democracy."

It was also a case of dedicated and experienced community activists running a sophisticated campaign. As Derek Shearer later told the national meeting of the Conference on Alternative State and Local Policies, it became apparent early on that the way to win in Santa Monica was not "to appeal on rational grounds." Instead, the renters' rights coalition came up with what Shearer described as a series of "Alinsky-style media hits," variously publicizing a "tenant dying of cancer" and a "70-year-old" widow who had been evicted in tears by her niece—the mayor, no less. Community organizers became adept at dealing with tenants who protested that their landlord, anyway, was a good guy—"He hasn't raised the rent in five years." "That's what we're trying to tell you," the answer would come back; "the place is ripe for speculation." Above all, the left kept up the moral offensive—apartment owners weren't mere landlords. They were "speculators" and "profiteers."

In responding to the leftist campaign, landlords found themselves handicapped by tenant resentment over Proposition 13 and what Santa Monica landlord Jim Baker calls the infrequent but nevertheless "horrifying" impact of speculation. Baker is a retired business executive with substantial rental property. He dresses like a yacht club commodore, wearing double-breasted blue blazers, white turtlenecks, a large gold anchor pendant, and a pencil-thin mustache. His front door is carved like a Polynesian temple, and his doorbell plays the opening notes to Beethoven's Fifth.

According to Baker, many landlords helped dig their own rent-control graves by failing to pass on to their tenants the Proposition 13 rent rollbacks promised them by Jarvis. Instead, the majority of them merely declared a moratorium on rent increases on the grounds that, "If I didn't do something to you, I did something for you." Understandably, the tenants were irate.

In addition, by Baker's account, there were in Santa Monica prior to the rent control victory on April 19, 1979 (a day Baker refers to as "Black Tuesday") certain "amateur" landlords who, through "misplaced compassion, economic ignorance, or cowardice," hadn't raised rents in 10 years. When in the middle and late '70s such landlords found themselves faced with soaring maintenance costs—the price of a new roof having quadrupled from $1,000 to $4,000, the cost of new rugs up from $1,500 to $6,000—they simply sold the buildings rather than jack up the rents. The result, as Baker tells is, was that "speculators" came in, snatched up the more obvious bargains, and then "restored six to ten years of fiscal neglect" in one fell swoop.

"Now, I'm not saying this was widespread," says Baker. He claims it probably didn't affect more than five percent of the units in the city. But in matters of this kind, it didn't take many such instances to have a large impact. There's no way, says Baker, to explain rent raises of $70, $80, or $100 a month to tenants—"They're going to want to take to the streets and lynch you," ignoring the fact that they've had "this tremendous sleigh ride for the past 10 years."

The leftists capitalized on the situation with allegations that tenants were being hit with sudden $150 rent increases all over town—which simply wasn't true, reply the landlords. According to statistics collected by the rent board itself, says Charles Isham, executive vice-president of a Santa Monica apartment owners' association, "approximately 55 percent of landlords in Santa Monica had not raised rents in one or more years" prior to the enactment of rent control. In addition, according to landlord attorney Lowell Wedemeyer, by the rent board's own records again, in the year before rent control was adopted rents citywide only went up 6 percent at a time when inflation was 13 percent. (Although the rent board has refused to make these figures public, board member Bill Allen confirms them.)

Landlord groups were also less than impressed with the rent control coalition's claims that it was a shoestring operation financed entirely by "the people." Santa Monica City Councilwoman Ruth Yannatta Goldway (wife of Derek Shearer) ran an organization called the Center for New Corporate Priorities, which in 1978 received $171,000 in CETA grants for job training. Over an 18-month period, the center placed 57 CETA trainees with 29 different community organizations, ranging from the leftist-activist Coalition for Economic Survival to the Tenants Action Council. These CETA employees, charge landlord groups, were really campaigning for rent control as well as for Ms. Goldway's election to the city council. Ms. Goldway, however, flatly denies that CETA workers did anything illegal. Cheryl Rhoden, a former CETA worker who also won a seat on the city council in November 1979, says the charges were greatly exaggerated—most of the CETA people didn't even know that she and Goldway were running for public office. (Following a Labor Department investigation and a report on it in the Wall Street Journal, however, Ms. Goldway renounced the unspent portions of the grants.)

Other federal funds used in ways that upset landlords, went to a Santa Monica community organization called Communitas. This group received a $250,000 grant from the Justice Department's Law Enforcement Assistance Administration to combat crime in the Ocean Park area of Santa Monica (home to Tom Hayden, Jane Fonda, Derek Shearer, Ruth Goldway, and most of the tenant activists), but some of the money was used to hire community organizers, compile precinct lists, and indirectly fund a pro-rent control community paper, The Ocean Park Perspective, which was then delivered door-to-door by Communitas people. In effect, says apartment owner Isham, federal money was being used to spread "rent control propaganda." This charge, local activists don't deny—or, rather, they acknowledge that federal anticrime funds were used for community organizing. According to a Los Angeles Times report, they argue that an organized community is a safe community. And anyway, they had explained "up front" when applying for the grant that they intended to use some of the money in areas not related to crime prevention in an effort to unify Ocean Park.

Whether or not federal funds were used to promote rent control, the renters' rights coalition was fabulously successful in turning out the vote. Whereas as recently as 1977 only 19 percent of eligible Ocean Park residents bothered to vote, in the last two rent control campaigns (one to pass the initiative and another to defeat a landlord attempt to water it down) the turnout in the heavily canvassed Ocean Park area was 65 percent—"all of which," says Cheryl Rhoden, "went for us."

How the West Was Won

(The Left's Moral Minority) Perhaps the biggest reason for the left's success in both Berkeley and Santa Monica has been its ability to capture the moral advantage, to create the impression that its demands for community control of housing are inspired by selflessness and altruism and that its true and only aim is helping the poor. The poor, as it turns out, are a valuable commodity. They are always trotted out as justification for rent control, even though the true beneficiaries are political activists and the middle class. "Rent control is a middle-class phenomenon," says UC Riverside economist David Shulman. The two California cities with the strictest rent control laws—Berkeley and Santa Monica—are solidly middle-class, even wealthy in fact.

As The Cities' Wealth itself admits, Berkeley is an unusually rich city, with over $1 billion a year in economic activity, which is twice as much as many cities its size. Stand on any downtown Berkeley street corner and throw a rock—you'll hit three banks and four savings and loans. Walk down any Berkeley street, and you'll find yourself passing cafes, boutiques, bookstores, gourmet restaurants, shops that specialize in champagne sausages and liver pate. You can buy bone china and order hot tubs in Berkeley; but if you should ever need a pair of work shoes, you have to take the bus to Oakland.

Many people in Berkeley dress as if they're poor—blue jeans and work shirts—but it's the kind of poverty that permits them to sit around in cafés all morning drinking cappuccinos at $1.30 a cup. To City Councilman Bill Segesta, such people are the soon-to-be upper-middle class—"They're in the position that one day the old man is going to die in Cleveland and leave them the proceeds of his law practice." They invariably have a college degree, if not several; and although they may be poor today, tomorrow they can be earning $25,000 a year, "because those are…the streams they fish in." Try going to a public meeting sometime, advises Segesta. The people who get up to speak are either lawyers, doctors, or architects. "It's never some poor schlep who works at Ford—that's unheard of."

During public hearings over rent control "it became very clear," says Segesta, "that if Berkeley did have a working class, it was the landlords"—they didn't have university degrees; they weren't sophisticated about investments; they worked for wages, saved their money, and bought apartment houses. Nevertheless, during the hearings they were attacked by tenant organizers, called "pig landlords" by young, white, middle-class Berkeley activists who, as Segesta says, have "trust funds" and "inheritances" and "had gone to college by virtue of their dad being a fancy eye surgeon back East."

In the Berkeley newspeak, however, tenants are the oppressed masses; landlords, fat capitalists. This despite the fact, says rent board commissioner Martin Overstreet, that one-fourth to one-third of the city's landlords are black.

"A couple of months ago," says Overstreet, "I got a frantic call." It was from a black man, a letter carrier, 62 years old with mandatory retirement staring him in the face. He had, some 18 years earlier, bought a slum and fixed it up. Now the four white, middle-class students he had for tenants had gone on a rent strike. "And all of these students will take a degree," says Overstreet, "and parlay it into these $25,000-a-year jobs." Five years from now their politics will have shifted 180 degrees, and they'll own portfolios and be talking on the phone to stockbrokers. But in the meanwhile, they're withholding rent from this elderly black man because he's a landlord and therefore a "criminal," a "slave-keeper."

Charles Isham, too, disputes the moral distinction the left always makes between landlords and tenants. What difference does it make, asks the Santa Monica apartment owners' spokesman, if "one just bought an apartment and the other bought AT&T stock"? The stockholder at least has the chance to match the inflation rate, but now the apartment owner is limited to whatever profit crumbs the rent board throws his way. (The Consumer Price Index has gone up 29 percent in the 18 months after rent control was enacted, while rent increases over the same period were limited by the Santa Monica board to 13 percent.)

The Santa Monica rent board has gone so far down the road toward "a class warfare state of mind," says landlord attorney Lowell Wedemeyer, that it now sees all property owners as "evil" and only tenants as "impoverished," and "downtrodden." In fact, he says, many small landlords don't have any retirement pensions. "They chose to put their labor and their money into an apartment building," one of the few ways people without a great deal of financial sophistication can protect their savings from inflation. By refusing to recognize that fact, says Wedemeyer, the rent board is "making paupers out of these people."

As Berkeley and Santa Monica go, so goes the nation. That is the goal of the left—to win control of certain vulnerable cities and then, using those cities as a "secure base," to expand outward until, having won in enough cities, they can, in the words of Derek Shearer, "talk about running someone for president and changing national policy." Rent control is clearly just the opening shot.

Berkeley is already in the leftist column, with progressives controlling the rent board and five of nine city council seats. In Santa Monica, progressives control all five seats on the rent board (the left ran a unified slate, while the opposition split its vote over some 59 other candidates) and three of six city council seats (one seat is currently vacant, the previous mayor having died in a plane crash at sea). If the left can win two of the four openings in April's city council elections, their first step will be to hire what Shearer calls "a progressive city staff," not only to support them administratively but to enable them to schedule progressive national conferences in Santa Monica, which by then will be in the process of becoming what Shearer calls "a progressive model city." Once media attention was focused on Santa Monica, the city would serve as an example to the nation "of the way cities ought to be run." The problem is to win in April and then, as Shearer says, to "govern decently."

How Has the Left Governed?

(Democracy in Berkeley) In Berkeley, political power is currently in the hands of Berkeley Citizens Action, the object of emulation in The Cities' Wealth. A leftist political machine (it prefers to be known as a coalition) with roots running back to Robert Scheer's 1966 antiwar congressional campaign, BCA finally won a working majority on the Berkeley City Council in April 1979, after more than a decade of trying.

One of the council majority's first priorities was to get rid of the city manager they'd inherited—a ticklish job, since he was a black man, and there's a considerable body of leftist opinion in Berkeley that holds that one should never, for any reason, oppose a black who has managed to win public office. When BCA did finally ease him out, they replaced him with another black, described by one exasperated city council member as "a middle-level bureaucrat from a third-rate university," whose principal qualification was that he was the candidate of a councilwoman whose defection to their side was needed by the BCA contingent in order to convert an elected minority of four into a working majority of five.

One thing the new majority has been able to accomplish so far is to create fear and frustration in the long-time city staff. According to a state-of-the-city report by the city manager in 1980, the "polarization" on the council is so severe that city staffers hesitate to identify problems for fear the council "might fire them." A position paper prepared by a new anti-BCA political group says the city staff is "severely demoralized" and many of the most talented and energetic people—including two city attorneys, the housing director, two special assistants in the city manager's office, plus various deputy administrators, associate administrators and analysts—have left in frustration." "Their talents and expertise are ignored and abused," the report continued. "They are permitted no authority to perform their tasks. They are burdened with demands for spurious reports and research. The Council majority is constantly confronting them with unpredictable and conflicting demands. Job security has come to rest precariously on political conformity." One long-time Berkeley resident active in the black community says he hates to go down to city hall anymore, because even before they ask you what you want, they first want to know "what your politics are."

At budget time, much of the BCA council majority's energy is spent in finding ways to increase taxes to support not only the city's extensive social service agencies but also several dozen nonprofit agencies. They have ordered parking meters installed in areas that didn't yet have them, increased parking fines, raised building permit and plan check fees (from $7,000 to $44,000 in one low-cost housing project) and, in last year's budget, attempted to raise $295,000 by imposing $40-$100 fees on businesses for what Councilwoman Shirley Dean calls a "nonexistent fire inspection"—"They never intended to give it," says Dean, "there was no program attached." At one point, they also introduced a plan to save $34,000 by demoting 12 Berkeley police officers on the grounds that the department was top-heavy with senior officers. But they had to back down when it was discovered that the people most affected would be women and blacks.

In another instance, they tried to save money by requiring people to carry their trash cans out to the street (at present, Berkeley trashmen come into the backyards and pick it up themselves). But they failed to take into account opposition from senior citizens and the black sanitation workers union.

They did successfully raise permit fees for sidewalk food vendors from $40 to $1,500 when they were told that one supposedly low-income fruit juice vendor was clearing $70,000 a year. And they created an architectural review board to approve design of the food carts.

Undoubtedly their biggest coup, however, was Measure E, a library tax. The city wanted more money for social services. Knowing that an ordinary tax increase was likely to be defeated, they appealed instead to the vanity of the voters—Berkeley was one city, by God, where people respected learning, and they weren't about (post-Proposition 13) to let the library lights go out just to save a few crummy bucks. The measure, which promised to free over $2 million from the general fund and provide the libraries with an independent tax base, passed overwhelmingly in June1980. "The library was the only thing we could have done it with," says leftist City Councilwoman Florence McDonald (mother of Country Joe McDonald). "It was like brotherhood and apple pie."

A major factor in the left's continued success in Berkeley has been its ability to attract and hold the student vote, especially on issues like rent control, BCA partisans dominate the student government and campus paper, and there's a strong campus chapter of the Campaign for Economic Democracy. So far it seems not to have dawned on students that rent control might not be in their best interests. Given a choice, landlords tend to prefer older married couples to the marginal stability of students. Furthermore, because of the economic recession, graduate students are taking fewer courses, thereby stretching out their degrees. The result in the south campus area is that housing has become virtually unobtainable. A campus study shows Berkeley's 30,000 students now living an average of 6.3 miles from campus, up from 5.7 miles just a year ago. "It's tighter than ever before for students," says Councilwoman Dean. "Why students ever thought they would benefit from rent control is beyond me."

Far from making any pretense at fairness, the Berkeley rent board, in the eyes of landlord boardmember Martin Overstreet, rather sees itself as "the principal tool for expropriation of a landlord's property"—the entire hired staff "reads like a roster of radical attorneys." Even though the law requires deliberations of the board to be public, they hold closed executive sessions under the excuse that the discussion involves potential litigation. What they're in fact, talking about, says Overstreet, "is how to organize tenants and how to organize rent strikes."

And when they do hold open meetings, instead of determining policy they spend all their time drafting regulations, correcting punctuation, dotting i's and crossing t's—"inane inefficiency," says Overstreet. They're mandated by law to grant annual general adjustments, but they've been caught between the requirements of constitutionality (under a 1976 California Supreme Court decision, rent control must allow landlords a "fair return" on property) and their radical supporters, who don't think that the 1980 rent control initiative was confiscatory enough. So because they don't know how to deal with the real issues, says Overstreet, they duck them and do what they "know how to do—housekeeping." In December 1980 they finally approved a general rent increase of five percent, but they haven't even begun to accept petitions for exceptions allowed for under the law.

Overstreet was appointed to Berkeley's rent board by (non-BCA) Councilwoman Gilda Feller and was the only landlord on the board. But when the property management firm in which Overstreet is a partner voted (against his wishes) to join a suit by 30 other landlords against the 1980 rent control law, the tenant board members promptly moved to expel Overstreet for conflict of interest.

Upon discovering that they had no such authority, they drafted a regulation for just that purpose and expelled him again. (Overstreet has since obtained a temporary restraining order reinstating him to the board). Actually, it wasn't any alleged conflict of interest that bothered the board, says Overstreet, so much as his insistence on reminding them of the economic facts of life—"They can't tolerate that alternative voice."

In response to what it considers the abject failure of private housing in Berkeley, the left has long promoted "nonprofit cooperative ownership of housing." The Cities' Wealth holds up as an example Savo Island, an attractive 57-unit townhouse complex in west Berkeley. Its directors consider the project so successful that they schedule tours for college students in city planning.

In fact, observes Martin Overstreet, Savo Island is a "massive failure that can only succeed with massive subsidies." Council woman McDonald confirms that residents of all but 10 of the units are subsidized by the Section 8 (rental assistance) program of the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development. The city of Berkeley laid out money—nearly a million dollars, according to Councilwoman Dean—for the project's "predevelopment" and land costs. HUD then guaranteed two construction loans at below-market rates—one at 3½ percent and the other at 7 percent. In spite of all these subsidies, the monthly payments for residents still run from $335 for a one-bedroom apartment to $650 for a four-bedroom. "I wish my rents were that high," says Overstreet.

How Has the Left Governed?

(Justice in Santa Monica) Derek Shearer's hopes of turning Santa Monica into a progressive role model for the rest of the nation's left got off to a slow start when the rent control victory left many of the city's landlords in a state of near hysteria. They packed the early meetings of the rent board, booing through the Pledge of Allegiance, invocation, and minutes of the last meeting, whooping and hollering when tenants tried to speak, and on one occasion becoming so unruly that board members had to leave city hall under police guard. One woman who tried to protect Legal Aid attorney Robert Meyers (author of the rent control initiative) from a jeering, shoving crowd was herself slugged by a realtor (she later collected $1,500 in an out-of-court settlement).

Cheryl Rhoden, city councilwoman and staff member of the Campaign for Economic Democracy, was threatened on her answering machine. Anonymous callers attacked board member Gerald Goldman as "a communist jew pig" and suggested that he "go back to Russia." His garbage cans were overturned in the night. One morning he discovered that someone had beaten his Porsche with a ball bat and crowbar. One person wrote to attorney Meyers claiming that Meyers was suffering from an advanced stage of "dementia" caused by "the poisonous infections of his brain from the fluids created by his misguided hatred of the free society in which we live." Although in Meyers's opinion the rent control law "hasn't made landlords treat their tenants with any more decency," at least it has exposed landlords for what they really are—"greedy, violent people who use almost any tactic to exploit their tenants."

In spite of their raucous behavior, Santa Monica City Councilwoman Cheryl Rhoden says she feels sorry for small landlords making their first appearance before the rent board. It was obvious they weren't used to dealing with governmental authorities. Their voices quavered and their hands shook. "They were so scared," says Rhoden. And the irony of it all was that they "were upset over things that weren't true—they thought their savings and property were going to be confiscated."

But what else can one call it, asks Santa Monica apartment association director Charles Isham, when the board grants a "permanent $35-a-month rent reduction" to a tenant because his garbage disposal broke down on a Friday night and the landlord didn't get it repaired until the following Monday morning? Or what about the time a tenant complained that the previous occupant of the apartment had broken off "eight of the little rubber prongs that hold up the dishes in the dishwasher" and there was "a slash in the screen of the laundry room," and this merited a "permanent $81-a-month rent reduction"? Both of these cases were appealed to superior court and both were overturned, "but don't forget," says Isham, that "it cost the owner $5,000 to overturn that little $35 a month."

When first proposed, rent control was touted to the voters of Santa Monica as a lean, trim operation, costing no more than $400,000 a year. Furthermore, since landlords would be supporting the entire cost with their registration fees ($12.50/unit/year), it wouldn't cost the tenants—or the city—a thing. The first thing that happened (Berkeley suffered the same fate) was that many landlords simply refused to pay a fee that they felt was only going to be used to finance a board whose whole thrust was to deprive them of as much of their property as constitutionally permissible.

In the meantime, during the first 18 months of its operation, the cost of the rent board mushroomed from the original $400,000 estimate to $1.7 million for the current fiscal year. They now have the equivalent of 55 full-time staff people, including hearing officers, attorneys, and their own prosecutor. To raise additional money, they've been forced to increase the annual registration fee from $12.50 to $48.00 a year and this time around allow landlords to pass on the cost to their tenants. Rent Commissioner Goldman says most tenants gladly pay the $4 a month "to save $100 a month." Isham, meanwhile, estimates that if they continue spending at the same rate, next year the annual fee will have to be raised to $100.

"No one expected the workload and lawsuits that [the rent board] has had," complains Rent Commissioner Neil Stone, bristling with indignation at any intimation that the board is unduly overgrown and bureaucratic. "The assumption that the public sector is more efficient than the private sector is pure rubbish." And it's "hard to realize," he says, but "we are a brand-new government. It's not like adding a new department. We are creating an entirely new entity. That doesn't happen very often in this country."

And what extraordinary powers this "new government" has, notes landlord attorney Lowell Wedemeyer. It makes its own rules, acts as its own trial court, and then enforces its own decisions. "These people even have their own criminal prosecutors, and they just order them [the landlords] into criminal proceedings whenever they want to raise the stakes."

Because all five rent board commissioners were elected on a tenants' rights slate, landlords characterize the board as a glorified kangaroo court. Its rules, they believe, are designed to obstruct landlords at every step. Petitions for higher-than-general rent increases require filling out an 18-page form (a tenant's petition is two pages) and submitting three years' of personal income tax forms, which then become public record. Although the rent board was theoretically to have functioned as a kind of people's court, landlords have found that they need $75-an-hour attorneys to fight for their rights before the hearing officers. In the words of apartment owner Jim Baker, the officers are all "young aggressive adversary attorneys," and unless a landlord is experienced in such proceedings he'll find himself "chopped to pieces."

If a landlord is dissatisfied with the ruling of the hearing officer, he can appeal the decision to the rent board. If, as most often happens, he is unhappy with the board's decision as well, he then has the option of taking the matter to superior court. Because the legal costs of such appeals often run as high as $5,000, most landlords don't bother to proceed—a fact, says Charles Isham, that the rent board counts on. In those instances where landlords have appealed negative decisions on their rent increase petitions, they've done very well, he says, winning "all but one out of a total of 25 or 30. (Some 90 other writs are currently pending.)

A victory in superior court doesn't automatically solve the landlord's problems, however. The rule of administrative law is that the court does not substitute its own judgment or discretion within the area of the defendant agency's jurisdiction. In most instances, the court merely orders the rent board to rehear the case from the top.

The defect in the system, says attorney Wedemeyer, is the court's erroneous assumption that the landlord is getting a fair hearing from the rent board; "But what kind of a fair judicial hearing do you get from an adversary that represents the other side, and who says up front, 'I represent the other side—that's my job.'?" The landlords have no "economically viable method of achieving justice," he concludes, "because the courts are too cumbersome, too slow, too expensive, and the attorney's fees are grossly in excess of any cash flow benefit."

"I can't get any justice for these people," says Wedemeyer. "I do my damnedest, and it is just not available."

What the Left Really Wants

(A Personal View) I sometimes think the left has such a hidden agenda that they don't fully understand it themselves. On the surface, they talk about democracy, equality, social justice, and compassion. What they really mean is power.

As I interviewed various leftists for this article, I had a recurring conversation. In their view, virtually all of this country's social and economic ills are in one way or another related to corporate abuse of power. Corporations ruin the economy, destroy jobs, promote materialism, and trivialize the intellectual atmosphere. And the bigger they get, the more evil they become. Worst of all are the multinational corporations, which are independent governments, complete unto themselves, and totally outside any societal control.

When they'd finished, I'd offer my point of view: "Look, I'm no friend of corporations, and you can't get me to defend them, but in the grand scheme of things I'm a lot less afraid of them than I am afraid of the US government. I mean, if I decide not to buy a new Citation, there's nothing General Motors can do to me. But just let me decide not to pay my taxes some time, and sooner or later someone shows up on my doorstep with a gun in his hand.''

I'd then go on to explain my theory of personality types. As I see it, there are two kinds of people in the world—those who are content to live and let live and those who have a vision of some ideal society that they want to impose on the rest of us for our own good.

Now, among the live-and-let-live types, I suggested, are businessmen who, whatever else their faults, at least don't go around trying to impose their own values on their customers. In fact, their whole thrust is just the opposite—to find out what their customers want and then to fill that need so well that people will actually be willing to reach down into their pockets and pay for it. The visionary types, on the other hand, are the leftists. They decided in advance what an ideal society should consist of, and all that remains is to get the rest of us to go along.

At this point, I'd usually find myself accused of naivete (if not a good deal worse). How innocent of me, they would say, to think that corporations in any way care what their customers want. In fact, they told me, most companies take the opposite view. First, all the white male executives get together in the conference room and decide what it is they want to sell, the price they want to get, and the advertising budget required to make people now go out and buy it.

But surely, I'd say, you don't think people are so stupid that they would buy something they don't need and can't use just because they saw it advertised on TV?

In fact, that is exactly what they meant. And the more I talked to them, the clearer it became. Basically, leftists are people who feel fundamentally powerless—not only powerless to resist television advertising, but in a real sense powerless to control their own lives. To be a bit metaphysical about it, it seems to me that the leftist view of the human condition is that we are all particles of dust, buffeted and scattered by the universal cyclone, and our only hope, if we have a hope, is to join hands in some comradely fashion, pull together, and thereby hold the howling cosmic wind (temporarily) at bay.

As to why this should be, I don't know, but I'm sure it's related to what I've long observed as the tendency of leftists to feel as if they can't cope with the physical universe. Most of them, it seems to me, are technologically incompetent, a characteristic they take pride in when they aren't railing against overpriced plumbers, unscrupulous auto mechanics, and planned obsolescence in general.

I remember once, 10 years ago, sitting in a Berkeley park listening to an antiwar rally, the culmination of which was a speech by Tom Hayden. At one point the mike went dead, whereupon the moderator variously tapped on it, blew in it, and jiggled the connections until suddenly the sound returned. "The spirit of the people is greater than man's technology," he announced, whereupon the crowd responded with loud cheers. That was the way people used to think in Berkeley (and many still do). They saw technology as some kind of malevolent magic that can only be overcome by an even greater force—the mystical spirit of the people.

To give another example: When I recently interviewed SDS cofounder Richard Flacks (now a sociology professor at UC Santa Barbara), he at one point referred to himself as "technologically inept"—a small point, to be sure; but in talking to leftists, I keep encountering the same familiar attitude. A few months ago, while talking to an official of the Foundation For National Progress (publisher of Mother Jones), I asked why it is that the implicit thrust of so many of that magazine's articles is the need to regulate corporate activity. Her answer was almost a wail—"But they've got all the science and technology."

To me, this is a key point. If, for whatever reason—urban upbringing, middle-class conditioning, or genetic inaptitude—a person feels he can't manipulate the physical universe, then that person obtains his sense of security in the world by seeking to manipulate those people who actually do the building, growing, and manufacturing of those things we need to survive. Now, no one begrudges the left power over their own destiny. The problem is that they want power over everyone else's destiny, too. This is why it's hard to compromise enough to satisfy the left. Their announced agenda might be equality, fraternity, and redistribution of the wealth, but their subconscious need is really for power. And no matter how much they win or take, it isn't likely ever to be enough.

Paul Ciotti is a free-lance writer who lives in the Los Angeles area. He has a B.A. in humanities and a B.S. in mechanical engineering from Columbia University. He spent five years in the Navy "chasing Soviet submarines" and lived in Berkeley, California, for eight years pursuing a graduate degree in journalism.

THE "LIMITED-EQUITY" RIP-OFF

This graph illustrates the difference in equity build-up in a conventional stock cooperative and a "limited-equity" co-op. In the former, just as in a single-family home, equity is the difference between the market value of a property and one's unpaid mortgage balance. In the latter, however, equity is limited (as a condition of buying in) to an annual percentage increase on the amount of one's downpayment—typically some fraction of the annual increase in the Consumer Price Index.

For comparison, we assume two physically identical apartment buildings organized as co-ops, with units priced at. $40,000. In each case, to promote affordability, the down payment is just $2,000 (five percent). The bottom two curves show the equity build-up as the $2,000 down payment is augmented by either 6 or 10 percent annually (typical values in actual limited-equity projects in California). The upper curves show the much larger equity build-up—starting from the same $2,000—based on property appreciation in the conventional stock co-op and assuming a 12 percent, 30-year mortgage. Even if the property only increases in value at 2.5 percent a year, at the end of 10 years the purchaser has almost $16,000 in equity. For greater rates of appreciation, the equity build-up is far greater.

What a limited-equity co-op does accomplish is to keep the "price" of units artificially low and therefore permanently below market levels. While this benefits new members when they buy in, it does so at the expense of equity build-up over time for all members. And equity build-up is the principal value of home-ownership. Conventional stock co-ops and condominiums are the traditional way for lower-income people to take the first step on the ladder of home ownership, building up enough equity to move up to something better later on. The limited-equity co-op cuts this rung off the ladder altogether.

—Robert Poole

THE LEFT'S INTERLOCKING DIRECTORATES While America's been "turning to the right," the left has been busy building the political, institutional, and intellectual scaffolding that will allow them to push through their agenda:

• Citizen action groups. They may have as many as 75 people on their staffs and encompass several states. They tend to be aggressive in canvassing, lobbying, running initiatives and referendums, and, in some instances, running candidates for public office. Some of the best known are Massachusetts Fair Share, which claims a membership of 20,000 families; Ohio Public Interest Campaign (OPIC), which has a newsletter going to some 15,000 households; Connecticut Citizens Action (CCA); Illinois Public Action Council; the Hayden-Fonda Campaign for Economic Democracy; the New Orleans-based Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN), organized in 11 states; the Movement for Economic Justice; and various public interest research groups—PIRGs—invented by Ralph Nader and funded by college student fees.

• Nonprofit policy research centers. These groups hold conferences, support researchers, publish newsletters and books, and collect and disburse funds from and to other nonprofit foundations (see funding data below). Prominent among them are the Washington, D.C.-based Institute for Policy Studies (IPS); its former West Coast arm, now independent, the Foundation for National Progress; (Gar Alperovitz's) National Center for Economic Alternatives; the National Center for Policy Alternatives (parent to the Conference on Alternative State and Local Policies); the Industrial States Policy Center (Cleveland); the California Public Policy Center (Los Angeles); the Institute for Community Economics (Cambridge, Mass.); Community Economics (Oakland, Calif.); Planners Network (San Francisco); etc., etc.

• Progressive coalitions, such as the Citizen/Labor Energy Coalition led by William Winpisinger, president of the International Association of Machinists & Aerospace Workers; Citizens for Tax Justice; the Progressive Alliance, led by Douglas Fraser of the United Auto Workers; and the Conference on Alternative State and Local Policies.

The Progressive Alliance is a network of more than 100 organizations, including the UAW, the Communications Workers of America, the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, and the International Ladies' Garment Workers Union (in all, 25 trade unions are members); environmentalists (including the Sierra Club); citizen action groups (such as Mass. Fair Share); the American Indian Movement; IPS; and Marxist Michael Harrington's Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee.

The 1980 Steering Committee of the Conference on Alternative State and Local Policies included representatives from citizen action groups (OPIC, CCA, and others), labor unions (Machinists), policy centers (IPS and others), and other progressive alliances, as well as elected local officials from across the country.

• Elected officials and leading lights, such as Ron Dellums, elected to the US House from the Berkeley, California, area; Georgia State Rep. Julian Bond, Detroit City Councilman Ken Cockrel; New York City Councilwoman Ruth Messinger, and Texas Railroad Commissioner Jim Hightower; Derek Shearer, Michael Harrington, and Marcus Raskin.

• Publications, such as Working Papers for a New Society, Mother Jones (published by the Foundation for National Progress), and In These Times, a weekly published by IPS.

• Alternative Institutions, such as food co-ops, worker-owned stores, newspapers, schools, technology consulting groups, and demonstration projects. Providing noncapitalist training for such institutions' "coordinators" (managers) is the New School for Democratic Management, an alternative business school started by the Foundation for National Progress and assisted with funding by the National Consumer Cooperative Bank, a taxpayer-funded federal agency.

Where does the money come from? Here is a partial listing of grants reported in 1979.*

Shalan Foundation

$5,000 IPS

$15,000 Movement for Economic Justice

$15,000 Industrial States Policy Center

$21,000 National Center for Policy Alternatives

$10,000 Ohio Public Interest Campaign

$5,000 Public Interest Economics/West

Stern Fund

$20,000 Institute for Community Economics

$15,000 Movement for Economic Justice

$20,000 New School for Democratic Management

$20,000 California Public Policy Center

$25,000 National Conference on Alternative State and Local Policies

New World Foundation

$15,000 Movement for Economic Justice

$20,000 Industrial States Policy Center

$21,000 National Center for Policy Alternatives

Field Foundation

$35,000 IPS

Charles Stewart Matt Foundation

$15,000 Community Economics

*Source: The Foundation Center

—Paul Ciotti and Marty Zupan

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Socialism...on the Street Where You Live."

Hide Comments (0)

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mute this user?

Ban this user?

Un-ban this user?

Nuke this user?

Un-nuke this user?

Flag this comment?

Un-flag this comment?