REASON Interview: Arthur Laffer

A California economist talks about his curve, his critics, his case, and his conversion.

Economists are easy to identify. They're introverts, having learned from bitter experience not to let out a peep about "opportunity costs" at cocktail parties; they rarely utter a syllable that didn't first appear on the print-out of an electronic computer in the economists' native tongue of matrix algebra; they are exceptionally eager to neutralize anything of substance they might say by instantly offering you what might be true "on the other hand"—which is why Harry Truman so lusted for a "one-armed economist. " It is little wonder, then, that most people are surprised to meet Arthur Laffer—economist Arthur Laffer.

While possessing all the academic tools attested to by a Ph.D. from Stanford University (and the earning of tenure on the University of Chicago faculty at the age of 28), Laffer clearly bounces to a different drummer. He knows what the computers say—but he speaks to everyday political issues and the man-in-the-street. He is not afraid to stake out a clear policy prescription. The man rarely hedges his bets.

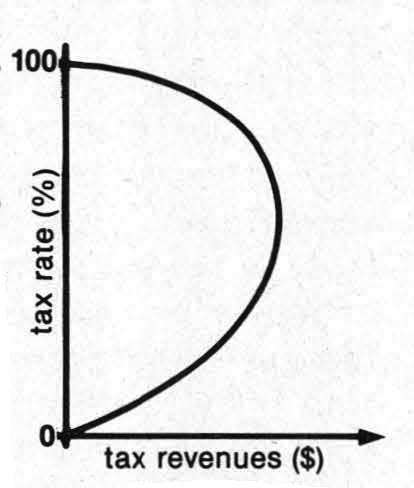

Dr. Laffer's brand-name logo has become the Laffer curve, an elementary graphical exposition first formally detailed on a Washington, D.C., cocktail napkin. The figure shows the relationship between two variables: the tax rate and the total taxes collected (government revenues). If the tax rate is zero, for example, tax revenues are likewise zero; but, Laffer further points out, if the tax rate were to be raised to 100 percent, government revenues would remain at zero—because no one works for nothing. In between these two extremes, tax rates will yield some positive level of revenue to the government, but the key point Laffer makes is this: Raising rates does not always raise tax dollars. In other words, making the tax burden more onerous may give workers and investors such a strong signal to stop producing that the diminished level of output that results may well yield the government even less money—in spite of the fact that it receives a larger percentage.

In the overtaxed, overburdened America of 1981, a lot of this simple thinking is making a lot of sense to people who may not be so simple. Yet its greatest import may be its impact on those who are: the politicians. Laffer talks to them—or more precisely, with them—in plain, appealing language. And since his is the talk of tax cuts, REASON thought it would be valuable to send economist and REASON columnist Thomas Hazlett to talk with the controversial Art Laffer on the campus of the University of Southern California.

REASON: Let's talk about the Laffer curve. Why do I always see the word optimum next to the point that maximizes government revenues?

LAFFER: That's because whoever is writing about it has made a mistake. What they're really talking about is a profit curve, as opposed to a revenue curve, and it's easy to confuse those two when you're not an economist. If it is a profit curve, then that point is the optimum. If it is a revenue curve, however, it's clearly not the optimum.

REASON: Where is the optimum?

LAFFER: I don't know—but what I do know is that it is clearly below that point. At that point, you can maximize government revenues but everyone knows that is clearly excessive taxation.

The thing is, it's a pedagogic device that allows one to explain the point to a congressman or senator very quickly and get them to understand the point. When the Treasury says that we've raised tax rates by 10 percent and therefore we are going to get 10 percent more revenue, that's nonsense. We know we're going to get less than that 10 percent. Now, whether we increase revenues at all or actually lower revenues from the starting point, that requires empirical estimate. The whole point of the curve is to illustrate this and to make it so that, when the congressmen get together to discuss tax legislation, they do not foolishly make the mistake that every time you raise taxes you collect more revenue and every time you lower them you collect less. This is not true. What you want to do is look at the constellation of tax rates and then try to get the optimal tax structure, given revenues. Then the optimal spending structure. Then the optimal level of taxation and spending. I use the Laffer curve to make a straightforward point which is obvious in another context: you can overprice your product and lose money because the quantity you sell falls off; and you can underprice your product and lose money because the increase in volume doesn't make up for the decline in revenues. What you want to understand is that taxation and revenues are not related in a one-to-one fashion.

REASON: Milton Friedman has branded the Kemp-Roth tax-cut bill—and you are the moving force behind it—as a free lunch, the Kemp-Roth free lunch. Do you think that's the right way to view it?

LAFFER: Then it's a perfect example of a case in which we should all support a free lunch! If you can lower tax rates without lowering revenues, I know no one in his right mind would say you shouldn't do it. I mean, if you provide more private incentives and you expand the private sector without hurting the government sector, why shouldn't you? The question then is: Is it conceivable that that's true? And I think the answer is clearly yes. Milton's written a number of pieces where he shows free lunches, where something he's proposing does nothing but benefit every group. In one of his Newsweek columns he talked about cutting the highest tax rate to 25 percent, and you'd clearly get more revenues, he said, and you would make individuals work harder. Fine. I love it. I think that's a better proposal probably than Kemp-Roth.

REASON: The first place I heard about a Laffer curve was in a Milton Friedman column several years ago.

LAFFER: A column about capital gains taxes, where he argued for the free lunch. I think he was right that time, and I think he's right now. I think to tag it a free lunch and therefore make fun of it is nonsense.

REASON: Now, what problems do you have with Margaret Thatcher?

LAFFER: She raised taxes when she came into office after promising to lower them. And I wrote a piece in the Wall Street Journal on Margaret Thatcher's tax increase, and I was disinvited from a lecture tour of Britain on that day. I'd spent a lot of time with her and several others in Great Britain, but they raised taxes. And you look at the results. Their deficit is not disappearing, their interest rates have not fallen, their inflation rates have gone up, and their unemployment rate has gone way up. I think it's a classic case of raising taxes and lowering revenues. And causing inflation.

REASON: If we put through a Kemp-Roth bill and the deficit actually got bigger, then inflation would presumably increase…

LAFFER: Why?

REASON: Well, because the Federal Reserve is going to cover that deficit by increasing the supply of money.

LAFFER: Well, wait, let's take a look. What's the relationship between the deficit and inflation?

REASON: Well, what is it?

LAFFER: No direct relationship there. If we run a larger deficit, let's say, there's no reason why we have to monetize it.

REASON: The common view is that if we don't monetize it, then there's a depression.

LAFFER: Why?

REASON: Because there's no capital for the private capital market.

LAFFER: Oh, but the whole question is incentives. You're the Fed: would you tend to have easier, or looser, monetary policies if the economy is declining or increasing?

REASON: I'd run looser if it's declining.

LAFFER: Yes. Well, now, does Kemp-Roth increase incentives, increase output employment, even if it doesn't pay for itself?

REASON: Yes.

LAFFER: Okay, then in a growing economy—if Kemp-Roth has passed, the economy would be growing faster than it would otherwise—the Fed will have less pressure on it to run loose money. So I would argue that really by cutting tax rates, even if you do run a larger deficit—and I'm not at all sure that you will—but even if you do, you'll have less pressure on the Fed to monetize that debt.

REASON: Well, why doesn't Friedman like this?

LAFFER: I don't know. That's for Milton to answer, not me. I think Milton Friedman has backed Kemp-Roth if I read his statements correctly. I think Alan Greenspan does, I think George Shultz does. I think these all do. And I think that what we mean to say is that there are a lot of things other than Kemp-Roth that are important, and one does not look at one policy in a vacuum. I think Milton would like to cut government spending. I would too. But the easiest way to cut government spending, frankly, is to have a growing economy, because when you cut taxes and expand the private sector, you reduce the problems that are the government's bailiwick—unemployment, most obviously. If you cut in half the number of people unemployed, you're going to reduce unemployment compensation. Halve the number of people on welfare, and you're going to reduce the amount of welfare spending.

REASON: But you don't believe, then, that government expenditures are necessarily related to government revenue, that, if revenue is going up, government is automatically going to spend more?

LAFFER: No, I don't think that.

REASON: You don't think the politicians feel a constraint?

LAFFER: But now you're in a different area. I'm not a political scientist. But I see no reason why they can't use increasing net revenues for reducing taxes even further and further and further, nor why there's any inextricable link, why you have to starve government in order to get it to cut taxes.

REASON: What kind of actors are these bureaucrats? Don't they want to maximize their own incomes?

LAFFER: They're like you and me. They're American citizens, born and raised in the same…

REASON: If they're like me, why wouldn't they want to increase their own standard of living?

LAFFER: Well, they may well want to produce a job in the private sector and quit. A lot of my students go to work for government but would rather work in booming little businesses—which aren't around. One of the best ways of reducing government is by making the private more attractive, in my view.

REASON: So you have this model of government bureaucrats held hostage by a private economy that is not expanding rapidly enough for them, and as soon as it does, they'll gladly leave the government trough?

LAFFER: Well, I guess I see it a little bit differently. I mean, I don't like the concept of hostages. But the government is, for many of my students now, the best employer. It gives them the best jobs. If you look at the stock market over the last 10 or 15 years, you don't make a lot of money in the private sector these days, and you get all sorts of red tape and hassles. In the government, there's some pretty interesting jobs—especially for Ph.D. economists. Now, the question is, If we had the private sector growing like mad, would they be the same way they are? I don't think so. It's not that they're hostages; they're just choosing among alternatives, and they take the preferable alternative. Do you see what I mean? I don't view bureaucrats as any different from you and me.

REASON: Well, neither do I. That's why I'm saying…

LAFFER: They're wonderful people, and they try to be efficient. They don't want to waste, they don't want to squander, they don't want to destroy the country, and they aren't after some sort of maximizing for the bureaucracy. They're looking at their own private, personal incentives. If they're given free money, sure they're going to spend it if they can. But they don't do it to hurt the people.

REASON: But for any individual bureaucrat to cut $100,000 out of his one budget is not going to spur the economy such that he can get a job out in the private sector.

LAFFER: That's true.

REASON: So what are the particular incentives that are going to make them want to do that?

LAFFER: I guess from their own standpoint what they do is they look at the funds as being costless and they look at the spending as being revenue-gaining to them personally. And of course you want to change the structure of this. I mean, you want to have a good budget. We all agree that there's a lot of waste in government spending—because of these incentives.

REASON: So the case that you're making for government workers is dependent upon a very large change in the institutional structure of government.

LAFFER: No, not at all. I don't think that the pressures on any specific agency or department or guy down there on the line changes much whether the gross revenues are up or down. So why expect a noticeable change if more revenues come in?

REASON: Well, every department is certainly going to fight to get that money.

LAFFER: Well, aren't they now? Even though it doesn't exist, they're spending money they don't have. But what you're saying is that somehow the pressures on them to control their spending will diminish if revenues are larger. I don't believe that for a second.

REASON: You think there is no correlation between revenues and expenditures?

LAFFER: Yes, there is, of course—a gross correlation, but nothing like you're talking about, not in a micro sense.

REASON: I'm going to lock you in a room with James Buchanan.

LAFFER: Please! But, you know, you're talking about societies and States when you're talking about adding a dollar's worth of revenue where there's a partial effect on spending.

REASON: No. I'm talking about adding billions.

LAFFER: How many billions?

REASON: At the federal level?—$50, $60 billion.

LAFFER: Right, $50 or $60 billion. I don't think there will be any pressures on the budget side, on the spending side. Not if you do correct accounting systems.

REASON: So, if all of a sudden the government were to find out it had $50 billion more in its bank account than it thought it had, the budget would not be affected at all?

LAFFER: I believe that's correct, yes. That's all other economic conditions held constant now. But, you know, if all of a sudden they found that their debt bonds were bouncing, that would change things. There really are ways of changing spending by the financing side—but not by changing the composition of that financing side. Do you know what the deficit is if you take a full budget picture of off-budget items, of underfunding of interest-subsidized loans, of the increases in unfunded liabilities in the federal program? You've got a deficit of $400 or $500 billion. And you're telling me that $50 billion is going to change that! Now, if there were a change in the resource base of America, yes. But I think the government really looks more at the resource base of the taxed entity than at the amount that they have collected from it.

REASON: They look at GNP rather than taxes…

LAFFER: Well, whatever the appropriate number is, yes. But also what they look at is the path, and they see the decline in real production or the lack of growth in real production. And that starts putting pressure on them.

REASON: So this is why they're looking at tax cuts now.

LAFFER: I think so.

REASON: Now, there's another question. Progressive tax rates, economists agree, are a very big impediment to economic growth. From the government's standpoint, the optimal tax structure—to get the maximum revenue at the minimum cost—would be regressive tax rates.

LAFFER: Sure.

REASON: But we see in the real world progressive tax rates everywhere.

LAFFER: That's because they do believe that there is a relationship between the incidence of a tax and its burden. By taxing the rich and by giving to the poor, they somehow believe you make the rich worse off and the poor better off, which is nonsense. Any casual glance at New York City can tell you that—or Great Britain. What you see there and in New York City, of course, is the most progressive taxes and the most generous welfare variables. And if anyone thinks the poor are well off in New York City, they just don't know New York City. The same thing is true with regard to Great Britain. Highly progressive taxes and very generous welfare income-maintenance programs, and the poor are worse and worse off. And compare Jamaica with Bermuda. Which one does better by the poor? Jamaica, with high progressive taxes and big welfare spending programs, or Bermuda, with no income tax at all? Jamaica has poverty, despair, unemployment, bankruptcy. Bermuda—its taxi cab drivers send their kids to finishing school in Switzerland. The best way to help the poor is to create an environment where the poor can become well-to-do.

REASON: What about Communist countries, which have a tax structure different from this country's? How does that compare?

LAFFER: Oh, in many of the Communist countries they don't go after successful people. They don't tax at inordinately high rates. In fact, I don't think that they tax at higher rates if you make more, and they don't pay people for being unemployed. They don't believe in taking from each according to his ability and giving to each according to his need. I mean, in Cuba if a guy decides to quit working in a sugar cane field and sit on the beaches outside of Havana, what type of welfare benefits do you think he gets? Yeah, right, you giggle—but the point of it is, what type of welfare benefits do they get here? We are the Fabians. We take according to ability and give according to needs as we perceive them. And of course, what we do is we destroy the capability of the society to produce, and we increase enormously the dependence of people on the system.

These countries have got a lot of real serious problems in economics, but they are not in their tax structures. They have to do with the ownership of capital. They believe that the State can run decisions in investment, which I think is wrong. It cannot. But they have all sorts of other political motivation behind their spending programs—their inordinate fetish with the military, where you have all the technological developments going into military and not into consumer goods, and da da da da. These are not being run efficiently. But I don't think you can really knock the tax structure in the Soviet Union, given the revenues they're taking. What are the estimates of Soviet GNP? Substantially less than the United States, isn't it?

REASON: About half of ours.

LAFFER: Yes, and what's their defense spending? About 60 percent greater than ours. Imagine, that's a threefold increase in our defense spending relative to GNP. How many people think that that would really have as little effect as it has in the Soviet Union? In other words, given the enormous problems of defense spending they have relative to their output, they seem to be handling it quite well relative to how we handle it. People claim that defense spending is destroying our economy, unbalancing the budget. That's not what's doing it.

REASON: Well, now, what's your view of people like Lester Thurow, people who might be the American Marxists? You tend to be identified as a free-market classical economist…

LAFFER: I am.

REASON: But your view of Lester Thurow is that you have a lot more to agree on than disagree on.

LAFFER: I do not disagree with his analytic framework terribly. I disagree with his objectives, and I disagree with a lot of his empirical conclusions, if you will, in the system. In other words, to oversimplify Les Thurow, I don't think that people save because their incomes are high per se; I think people save because they make an after-tax rate of return on their savings. I don't think people work to get to pay taxes; I think people work to get what they can after taxes. The Keynesian and monetarist notion, that somehow people work because there is a job, I think is silly. I think people work because they get paid after taxes, and therefore this aggregate demand nonsense is just that. So Lester Thurow is much more along my line of thinking.

I just don't agree with his prescriptions and his recommendations concerning the ownership of the means of production. I think they should be held by private individuals, and the more privatized the property rights are, the better off we are, much along the lines of economists at UCLA and the University of Chicago in their perceptions of property rights. The work of Harold Demsetz I admire enormously. In that area I'm very much of a private-ownership person—that through individual action you basically, in general, will come to the public good. And Lester Thurow does not believe that at all. He believes much more in a dirigisme, that government intervention is the way to get to the public good, that we have to rein in the animal spirits of individuals and their basest aggressive tendencies and transform them into lovely little butterflies floating around from flower to flower doing the public good, as opposed to what they would be doing late at night. I think profit-hungry individuals create public good and that our real problem is that the government has imposed an enormous amount of wrong signals, the profit-hungry people today go into a Newport Beach condominium or go into tax dodges in Bermuda, as opposed to producing goods and services that feed our poor and our unemployed and our deprived. And if, in fact, the government got out, then we would eliminate poverty shortly the way we did before. We were the place that took the poor. We're now the place that precludes the poor. We try to prohibit Mexicans from coming into this country. Our Statue of Liberty says, Give us your poor, your disenfranchised and huddling masses; we'll make them rich. But now we say, You keep your poor and give us your rich—which is outrageous. We were the place where the poor could do it. We are now the place where the poor are prohibited from making it, with an income tax that basically stopped the poor from becoming well-to-do.

REASON: Would you be in favor of outright abolition of the income tax?

LAFFER: I don't know. It depends on what you put instead.

REASON: What about a value added tax?

LAFFER: Yes, I would much prefer to see a value added tax. I think the proposal of Russell Long is inordinately sensible—that you take the income tax and you lower it more than you increase the value added tax. I think the federal government should try its best to use the tax structure to raise revenues, not to redistribute income. That's a fundamental error, that they perceive that they can in fact change the distribution of income. I don't think they can.

REASON: Why not?

LAFFER: I just basically believe that the burden of total taxation is independent of the incidence of that taxation. And it's true with spending programs, too. Paying people to be poor doesn't mean that you make them better off. People respond to incentives. If you pay people for being poor, you cause them not to become well-to-do, and if you look at the effective tax rates in the inner city, it's enormously high. I did a little study here in Los Angeles of $300-5800 a month increases in income for a family of four—two adults, one wage earner. The family is literally worse off the more it makes because it loses so many welfare programs plus it pays income tax at a relatively high rate. [See "How to Perpetuate Poverty," by Bruce Bartlett, REASON, May 1980—Eds.] Outrageous. There are direct disincentives for people to improve their well-being by increasing their income.

REASON: Well, this is interesting because Lester Thurow's book, The Zero-Sum Society, offers basically a laissez-faire sort of socialism. He wants to deregulate, throw out environmental controls, the Department of Energy, rent controls, all that, and simply be left with an Internal Revenue Service that collects money and then redistributes it at the end, so that the only thing left of government would be this redistribution through the income tax.

LAFFER: Well, he and I agree very, very far along. I do not disagree about the first part, but that's an amazing thing. Can you imagine finding other eastern liberal economists who do agree with all those things? No. Basically, the point is he starts from the same general framework and model that I do. I just don't like his answers.

REASON: What are some of the major criticisms you have of the traditional neoclassical establishment economists?

LAFFER: No, no, let's say not neoclassical. They're not at all. In fact, they're demand-side, they're single-entry bookkeepers. They are partial-equilibrium economists who believe that people work because there's a job, not because they get paid, and they therefore have done everything without focusing on the substitution effects of fiscal policy. The substitution effects of fiscal policy—as anyone knows who has read Leon Walrus or read the first 110 pages of John Hicks's Value and Capital—substitution effects accumulate, and the income effects net to zero when your transfers match the taxes, and you've got to be very careful about how to handle this.

REASON: In layman's terms, what is your major disagreement with their conclusions?

LAFFER: Government spending, increases in transfer payments, reduce output. Increases in the quantity of money, with our progressive tax scheme, reduce output. Devaluations of the currency reduce output. But they believe that increases in government spending, transfer payments, increase output. They believe that increasing the money supply increases output. They believe that devaluation of the currency increases output. I think they not only are wrong; they've got the wrong side.

REASON: Well, you look at it from the supply side.

LAFFER: Both supply and demand, but, yes, I focus on incentives to work. And they focus on incentives to buy.

REASON: How do you plan to test the Laffer curve? Is this being done now?

LAFFER: It's being done daily. It has been for centuries.

REASON: Then give us some of the results.

LAFFER: Well, you know, you could take the case of New York City. Do you think for a moment we could balance the inner city's budget by raising its tax rate and driving the last two businesses out? Well, which cities are running surpluses and which ones are running deficits? I ask you. Look, which countries?

REASON: Tell us.

LAFFER: Well, look at Britain. Look at the United States. Compare it with Germany and Japan, which have cut tax rates. I gave you Bermuda and Jamaica as examples.

REASON: And are other economists testing out the Laffer curve?

LAFFER: Yes, at Stanford and Harvard and the National Bureau of Economic Research. They are doing it all over the place, and they're getting better and better results. In fact, I've never tested—and I don't know if I believe it or not—but I've never done the work to show that the Laffer curve works in the short run. Who has? Marty Feldstein argued it with regard to the capital gains tax, said it more than paid for itself right away. Mike Boskin has argued it. Mike Evans has argued it—these guys are the ones who are spouting the Laffer curve in the extreme form. I've been quite moderate in my responses. I've said to economists that I think that Kemp-Roth would pay for itself in several years. I said that Prop. 13 would within 10 years pay for itself. I've never made any more extreme statements than that. I think they're good, good proposals, and anyone who wants to balance the budget on the backs of the poor and the unemployed is really foolish. Teddy Kennedy put it correctly. He said the only way to balance the budget is to have full employment with price stability, and he's right. But he's wrong on how you get there.

REASON: But aren't we on a dangerous road here? Here Howard Jarvis went out, and in the simplest fashion possible, he put the question as the people versus the politicians and he won overwhelmingly. But if we start talking in terms of the empirical validity of where we are on the Laffer curve right now, isn't that going to change the whole argument?

LAFFER: It does to some people, sure. But, see, you're presuming that the only thing that is relevant is the revenues. I don't. Let's imagine we're going to have a large deficit forever but less people unemployed. I personally would be willing to experience a large deficit to reduce unemployment—if that were the true choice. Let's imagine that we're going to have a large deficit and lower inflation. I'd rather have lower inflation with a larger deficit than I would a smaller deficit and larger inflation. My belief. And these are the relevant choices, in my view. From the standpoint of my training as an economist, it's a side issue whether or not we make up that revenue.

REASON: Where did you do your graduate work?

LAFFER: At Stanford. I have an M.B.A. and a Ph.D. from Stanford.

REASON: How have the politics of the profession changed? You probably graduated in the heyday of the Keynesian gospel.

LAFFER: That's right. I was a full-fledged Keynesian.

REASON: What changed you?

LAFFER: Politics. I went to the White House for two years with George Shultz, and we tried good Keynesian policies, and we had the unemployment rate increase, the inflation rate increase, and the economy collapse. It led me to believe that maybe the model was wrong. Now, no economists back at the university thought it was wrong. They just said, "Oh, you didn't hold those constants," and they can say that in their little seminars. They said, "Ah, well, they didn't really do a wage-and-price freeze like we would have done it." Silly, silly, silly. Now take a look at what we've done here. We've increased government spending since Nixon came into office, enormously; we've increased the rate of growth of the quantity of money, enormously; we've devaluated the dollar, right, left, and center; we've put on wage-and-price controls. Now the Keynesian model would tell you that output growth would increase, unemployment would fall, and the rate of inflation would decline. What has happened?

REASON: Twelve years of economic bliss.

LAFFER: Yes, right, exactly. Now how many of those Keynesian economists from the university, who have never faced the real world, have changed their minds? How many of them who are in the real world, like Mike Evans and others, have changed their minds? That's the wonderful thing about being forced to live by evidence, because if you bear the costs of making mistakes, you tend to make less than if you don't.

REASON: Well, now, you probably aren't very often called a moderate when it comes to tax cuts, but Ed Clark, who was the Libertarian Party candidate for president, came out with a $150-billion tax cut.

LAFFER: He did not. He came out with a tax-rate reduction that would, under statical conditions, lead to $150-billion loss of revenues.

REASON: What would happen?

LAFFER: I think you'd lose much less than 150 billion dollar's of revenue, and with his stuff I think you'd spur the economy enormously. I think it would be quite beneficial to the country. I have nothing but praise for Clark's tax reductions, and I think he did an excellent job of proposing them, and I think his position is exceptionally commendable. I think the more power Libertarians get and the more appeal they have, the more they'll pull the rest of the world back.

REASON: So you think the Libertarian influence on the fringe of the political system is a positive force?

LAFFER: Oh, Libertarians are not on the fringe. I don't like that word. They're in the mainstream of a lot of my students.

REASON: A lot of your students at USC?

LAFFER: At the University of Chicago, too. The libertarian view of the world is by no means a fringe view; it's a very mainstream view of people who have thought a lot about this subject, and I don't want to have the libertarians categorized as fringe. I am not a libertarian, but I do not find their views either silly or ridiculous or fringy or kooky.

REASON: Where do you disagree with the libertarians?

LAFFER: Well, for sure, the League of Non-Voters. I believe very much in being an activist in your own area of expertise. There are also a lot of other personal views I have that libertarians and I might disagree on.

REASON: Victimless crimes?

LAFFER: I don't know. Maybe when this one's over we'll go into that heavily. But if anything my reason comes down to this: There is a structure that exists, and anyone failing to recognize institutions and operate within them is making a moderate mistake—I don't say serious mistake. So it's not that I wouldn't ever consider being a libertarian. But if I were a libertarian today my influence would be much less. It's silly to reduce my influence. I believe in practicality. Even if you don't think candy is good for someone, if you give the girl a candy so she'll go to bed with you, it works.

REASON: I think that's a good place to conclude. Thank you very much, Professor.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "REASON Interview: Arthur Laffer."

Show Comments (0)