Alternative Transit

While the feds continue to spend billions on money-losing subways and bus lines, these new forms of transit are meeting people's real needs-and doing it without subsidy.

Transit, we are told, is a classic example of a public good—something that must be provided by government, paid for by taxation, and put up with by all of us. The private sector has failed, we are told, and that's why government had to step in, taking over failing bus lines and subways. Moreover, now that energy costs have quadrupled, mass-transit systems are essential energy conservers, even if they do cost taxpayers a bundle.

The only problem with this set of propositions is that every last one of them is false. And besides serving to justify wasteful government transit boondoggles, they frequently obscure the real solutions to urban transportation needs—the diverse, flexible, private forms of transit that are springing up around the country despite their massively subsidized public competition.

The annual deficit of the public transit system is one of the fastest-growing items in many city budgets. From 1971 to 1976 transit deficits increased over 800 percent. During this period the cost of providing transit service increased at more than twice the rate of inflation, while transit farebox revenues increased at only half the rate of inflation. In the early 1970s, farebox revenues paid for a bit over 90 percent of operating costs; by 1979, however, revenues were paying only 48 percent. Of the 1979 deficit, about half was made up by local taxes, the balance by federal and state taxes.

Except in a handful of large cities that operate rail lines, mass transit usually means a bus system. Typically, it is the remains of one or more formerly private bus companies that went bankrupt and were consolidated by the city, the county, or a multijurisdictional transit district.

Most of the bankruptcies and takeovers occurred during the 1950s and '60s. During those postwar decades our metropolitan areas underwent a profound transformation. Vast acreage surrounding the central cities was converted to tracts of single-family houses, and automobile ownership soared. These demographic changes spelled economic doom for conventional fixed-route transit systems. The dispersion of homes greatly reduced the ability of a limited number of routes to serve the potential customers. And the proliferation of cars—aided by the cities' construction of expressways and freeways—meant that many fewer people needed to ride the bus.

Bus company managements responded to these changes in a rather simplistic fashion. They clung to their fixed routes and attempted to cover rising costs by increasing fares rather than devising new forms of service tailored to the changed market condition. Since transit demand is relatively sensitive to price, this only served to drive away even more passengers, leading to bankruptcies.

Political pressure induced many local governments to take over failing bus companies, on the grounds that lower-income people had to have some form of public transportation. The passage of the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964 provided large amounts of federal money to assist cities in buying the failing companies. Originally it was contended that such takeovers would solve the financial problems because (1) the lines would no longer have to pay taxes and (2) they would no longer have to make a profit. It was even thought that the systems would somehow be able to expand and increase ridership, thereby operating more efficiently.

But none of these fond hopes was realized. The real needs of riders have gone unmet. In most cases service has been reduced, ridership has continued to drop, and costs—especially labor costs—have soared. (In the period 1972-78 labor costs went up 300 percent in some transit systems!) The federal government is now providing operating subsidies to the systems its original capital-equipment grants were supposed to make self-supporting.

What went wrong? Basically, it was a failure to realize that a single system of fixed-route buses or trains does not meet the needs of people living in most modern metropolitan areas. Attempts to force-fit these systems into suburbanized areas will continue to fail and will continue to drain money from the taxpayers. What's needed instead are alternatives that can respond to riders' new needs in innovative and cost-effective ways.

SORRY SUBWAYS

In the past decade, the Urban Mass Transit Administration (UMTA) has been promoting an unworkable solution to large-city transit problems: build subways. Never mind that a subway is even more of a fixed-route, density-dependent system than a bus line. The idea seems to be that since subways "work" in New York and Montreal and Moscow (where population density is many times that of Atlanta or Denver or Los Angeles), they should work elsewhere. Subways can be made to look modern and technological so people will be dazzled by them, and they ought to get people out of their cars and off the streets (hence reducing traffic congestion and air pollution—and everyone's for doing that). Ergo, we'll build subways, and hang the expense!

Unfortunately, hanging the expense is just about what one has to do. The showcase modern subways are San Francisco's BART and Washington, D.C.'s Metro. BART's construction was funded by local bonds, being paid off by a special multicounty sales-tax override. It cost over $2 billion but carries only 130,000 passengers a day. A typical BART commute from suburban Orinda to downtown San Francisco costs $6.77, including interest on the bonds and "social costs" to neighbors. Figured on a comparable basis, making the same trip in a full-size car costs only $4.49; in a subcompact, $4.05; and on the bus, only $3.21. Excluding the social costs, the average BART ride cost $4.48 in 1975/76. Since the average fare was only 72 cents, the taxpayers had to make up $3.76 for every trip—more than five times the fare.

Washington's new Metro is subsidized even more heavily. When completed, the 100-mile system is now expected to cost $7 billion—that's $70 million for every mile of track. During its first nine months of operation, with fares running from 40 cents to 55 cents, each ride received a taxpayer subsidy of $10.38—more than 20 times the fare. By 1981 the taxes paid by each household in the area to subsidize the Metro will total $1,670—enough to buy a good used car.

Besides costing taxpayers a fortune, these new rail systems neither save energy nor reduce traffic congestion. Surveys show that they attract most of their ridership away from buses. So they do very little to reduce the number of cars on the road. And by depriving buses of riders, they serve only to worsen the dismal economics of existing bus systems.

A study by the Congressional Budget Office concluded that "under typical conditions, new rapid rail systems actually waste energy rather than save it." This is because (1) construction of rail lines, especially subways, is particularly energy intensive, (2) rail system riders still drive to and from stations in low-occupancy autos, and (3) the rail systems divert riders from much more energy-efficient buses.

Despite this overwhelming evidence, UMTA is charging ahead with rail lines as the panacea for big-city transit problems. Atlanta's subway is nearing completion, and other subways are on the drawing boards for Baltimore, Buffalo, Los Angeles, and Miami. UMTA expected to spend $16.4 billion between 1979 and 1982. From what we've seen, cities should avoid this "free money" like the plague. To get stuck with a transit system whose operating costs are 5 to 20 times higher than what fares will bring in has to be a raw deal for the city's taxpayers—especially when there are much better solutions that cost taxpayers little or nothing.

ALTERNATIVES THAT WORK

The key to solving America's transit problems lies in devising new forms of service that respond to the actual needs of a widely dispersed population. This requires that we find out what these transportation needs are, rather than remain fixated upon moving heaven and earth to get people to use a preconceived idea of what a transit system is supposed to be.

What is needed, in short, is an economic and legal climate that encourages experimentation and risk-taking—a free market, in other words. Unfortunately, in most urban areas there is anything but a free market in transportation services. Typically, there is a large municipal rail and/or bus line serving a limited number of fixed routes. There are also one or several taxi companies, in most cases heavily regulated as to the number of cabs, the areas served, and the fares charged. Any efforts to begin other forms of service are usually legally thwarted. They are immediately attacked by the municipal transit line or the taxi companies as draining away passengers ("skimming the cream") and therefore contrary to the public interest.

Should an entrepreneur persist despite these obstacles, he is likely to be classed as a "common carrier" by the state public utilities commission and forced to prove (a) that he is "fit, willing, and able" to provide the proposed service, (b) the operation is necessary for the public's convenience, and (c) the existing carriers are unable to meet the needs the entrepreneur proposes to serve. In some states he must even prove that he will not take any business away from the existing carriers—in effect, that he will not more adequately serve people's needs!

These laws, and the public attitudes that support them, have effectively preserved the shared monopoly of municipal bus/rail line and cartelized taxi industry in most communities. And that has left most people with no affordable alternative to the private automobile—despite mounting congestion, worsening smog, and rising fuel prices.

There are better ways. Here and there, despite the obstacles, private innovators have developed new forms of transportation service that respond to real needs. These new services are typically grass-roots efforts that require minimal investment and no tax funds. They go by the generic name paratransit.

Jitneys, gypsy cabs, shared-ride cabs, car pools, and van pools are among the many forms of paratransit. They vary in price, accommodations, and service levels. But they share the common characteristic of flexibility, which is very much in keeping with the decentralized nature of today's metropolitan areas. Until recently, they shared a more dubious distinction as well. All of these services (except for car pools in which no money changed hands) were illegal in most cities.

THE JITNEY TRADITION

Jitneys are small (usually 8- to 12-passenger) vehicles carrying passengers to various destinations, along relatively fixed routes, usually for a flat rate per passenger, but sometimes on a zone-rate fare. Jitneys are typically far less expensive than taxis, often costing little or nothing more than bus fare. Usually the jitney is owner-driven, though the driver may coordinate his operations with other drivers by belonging to an association. Jitneys arose in the 1914-18 period—the heyday of the Model T. In 1915 there were 62,000 of them, in every major American city. So successful were jitneys that they threatened to put the trolley lines out of business. Owners of the latter—generally well-connected politically—managed to have laws passed in most cities outlawing jitneys.

Elsewhere, however, jitneys often provide a major portion of a large city's transportation. Over half of all daily travelers in Caracas and Buenos Aires ride either jitneys or larger jitney-buses called colectivos. Smaller, more conventional jitneys play a major role in Santiago, Chile, and Lima, Peru. "Jeepneys" and free-market taxis provide 25 percent of all mass transit in Manila, 15 percent in Seoul. And in Tehran, jitneys and taxis constitute the entire mass-transit system.

In the United States only a few jitney services survive, and they are limited to particular areas of a few cities. In Atlantic City, 190 jitneys ply Pacific Avenue, the major thoroughfare serving hotels and restaurants on both sides of the Boardwalk. Two associations operate 117 jitneys along two routes in San Francisco: Mission Street and Third Street. The former serves the major business and commercial district, while the latter extends from the Civic Center to Hunter's Point, a black ghetto. All-black jitneys operate in Baton Rouge and Miami. Each runs between a black suburb and the downtown area. All the above are legal jitneys.

Illegal jitneys operate in a number of cities. In Chattanooga, 85 jitneys carry some 20 million riders a year. On a typical route the fare is 35 cents, with an extra 10 cent charge for going up to three blocks off the route—a flexibility you'd never find with the city bus line. Though officially denied, an illegal jitney service has operated in the black ghetto of Chicago for many years. In New York City the mayor's taxi commission estimated in 1966 that more than a thousand legal liveries (limousines) were operating illegally as jitneys or taxis, both downtown and in black neighborhoods. A St. Louis jitney system comprising 85 vehicles served the city's black neighborhoods from 1917 until it was suddenly put out of business in 1965 by the Bi-State Transit Authority.

In all of these cases—and in many more—jitney service springs up to fill a need for transportation that cannot be met by either buses (too few routes) or taxis (too expensive). In many cases jitneys arise to serve minority areas where bus service is sparse and taxi service nearly nonexistent. In Pittsburgh illegal jitneys, which outnumber the city's legal cabs, operate between downtown and black neighborhoods to the east of the city. Some parallel the bus lines, charging the same 40 cent fare, but for a little extra they will take a passenger home. Besides supplying convenient, low-cost transportation to low-income people, jitneys also provide self-employment to the owner-drivers, with compensation in direct proportion to how hard they work. Jitneys are a perfect example of a form of transportation that fits the changing needs of its riders.

THE CAB CONNECTION

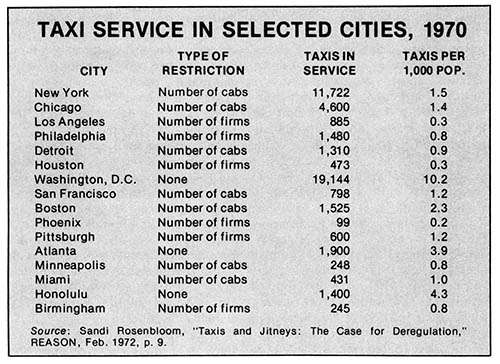

Taxis we already have, but in many cases restrictive laws are keeping them from providing the service that's needed. Studying the taxi industry several years ago, transportation economist Martin Wohl of Carnegie Mellon University reached a striking conclusion: "It is my view that changes in taxi regulation, pricing, and operation would markedly improve the availability, usage, and financial viability of cabs and probably do more than any other transportation improvement to lure commuters out of cars and increase total transit patronage." What he was talking about, in particular, was "lifting of barriers" on the number of taxicabs allowed to operate, the places they're allowed to serve, and the fares charged. The dramatic effect of regulating the extent of taxi service can be seen in the table. Cities that do not restrict the number of cabs or the number of taxi firms allowed to operate are cities with far more taxis per person.

Taxi representatives in regulated cities frequently claim that the legal number of cabs is all the market will support and that any larger number would simply spread the demand too thin for anyone to make money. This is utter nonsense, as the thriving Washington, D.C., market, with its 10.2 cabs per 1,000 people (compared with New York's 1.5 or Houston's 0.3) demonstrates. A variety of studies show that there is a large unfilled demand for taxi service in restricted cities. Poor people, homemakers, and students all use taxi service in considerable numbers—when sufficient service is available. But in restricted cities, cabs tend to concentrate on business users, serving the downtown, hotels, and the airport, and leaving residential areas greatly undersupplied.

Despite the laws, in many cities illegal gypsy cabs have sprung up to meet part of this unfilled demand. The New York Times has estimated the number of gypsy cabs in that city at between 4,000 and 5,000, mostly serving minority neighborhoods. Gypsy cabs cruise the streets openly in Cleveland's black Hough section and Pittsburgh's Hill district. Because they serve such a large market, gypsy cabs are often allowed to operate so long as they confine their operations to areas poorly served by licensed cabs. But because they operate outside the law, some gypsy cabbies take advantage of unwitting patrons, charging exorbitant fares under threats of violence or actually robbing them. But for many would-be cab users, it's either risk a gypsy cab or forget about taxi service.

The last few years have seen the beginning of a trend toward deregulation of taxi service. Major monopoly or near-monopoly cab companies have gone bankrupt in Los Angeles, San Diego, Philadelphia, and elsewhere, leading the first two cities to ease restrictions on entry and, in San Diego's case, to promote competitive pricing. Eugene, Oregon, deregulated taxi fares in 1978, as did Seattle. In each case, the happy result of deregulation is more service and lower fare levels.

Somewhere between conventional taxis and jitneys is the shared-ride cab. Like a regular taxi, this service uses a conventional sedan and provides personalized, door-to-door service. Like the jitney, however, it carries several passengers making different trips at the same time. Consequently, fare levels are a good deal lower than in regular taxis—although more than bus or jitney fares.

Unfortunately, most city governments—other than Washington, D.C.—ban shared-ride service. Two that don't, however, are Davenport, Iowa, and Hicksville, New York. In both cities, private cab companies provide low-cost, high-volume, shared-ride taxi service that appeals to many of the same people who ride bus lines.

In an extensive study of the Davenport and Hicksville companies, Prof. Kenneth Heathington of the University of Tennessee's Transportation Center found that their operating costs are much lower than those of the highly touted Dial-a-Ride systems funded by the federal government—systems that provide a similar kind of service but with a heavy subsidy. But the Davenport and Hicksville companies are private, profit-making concerns that don't receive a cent of tax money. They have simply found a ready market for this type of intermediate transit service.

POOLING

Transportation planners have recently discovered car pooling—a form of paratransit with significant potential for reducing congestion, air pollution, and energy use. Any large-scale use of car pooling requires that people who are otherwise strangers find each other and work out a suitable sharing arrangement. One of the smoothest ways to do this is for one person to be the driver and the others to pay to be driven. Unfortunately, in many states any such exchange of money is construed by the public utility commission as offering transportation service for hire—making the driver a common carrier subject to incredible regulations. The success of car pooling depends considerably on whether such absurdities of the law can be removed.

A pioneer in doing just that was Mrs. Garlene Zapitelli. Several years ago, fed up with rush-hour congestion and concerned about the energy crisis, she bought a Dodge van and began carrying fellow commuters to work, for a small fee. In short order, she was hauled before the California Public Utilities Commission and charged with operating an illegal bus line that unfairly competed with existing bus companies. Several appeals and many thousands of dollars later, the legislature voted to exempt for-hire car and van pools from state jurisdiction, provided the driver was a commuter.

With that decision, California became one of a handful of states—including Minnesota, Tennessee, Virginia, and Connecticut—to legalize car and van pooling. Commuters especially like van pooling because, compared with bus service, it offers door-to-door transportation and a semblance of privacy. And compared with driving your own car, the van offers a chance to stretch out and relax, sometimes in airliner-type seats with stereo music, at real dollar savings. A 12-passenger van, in fact, is more energy efficient than the new York subway, providing more than 110 passenger miles per gallon of gas.

The biggest growth in van pooling is occurring in the corporate arena; about 150 large corporations are now involved in such projects. The approach was originated by Robert Owens of the 3M Company in Minneapolis. Under his plan, the company provides—and insures—12-seat vans to volunteer employee drivers. The first eight passengers pay the company a monthly charge that covers all operating costs. The driver can add up to three more passengers to earn an income and can take the van home on weekends for a small mileage charge.

"The beauty of (corporate) van pooling is that everybody wins," says Owens. The company saves on parking expenses, commuters save $150-$750 per year in commuting costs, and the general public saves in terms of reduced congestion and pollution—as well as reduced demand for tax-funded mass transit systems.

SALVAGING BUSES

Bus service is not dead. Despite the changes in demand for fixed-route service, buses can play a role as part of an overall transit/paratransit system. Where buses still make sense is on heavily traveled commuter routes. And it is on these routes that bus service can pay its own way. It can even be turned back to the private sector.

Exactly that is beginning to happen in a number of metropolitan areas, with the phenomenon known as subscription bus service. The basic concept is simple. Employees in a large office or industrial complex who live in the same suburb band together and rent a deluxe, highway-type bus (reclining seats, air conditioning, music) from a private charter bus company. In some cases one employee obtains a bus driver's license and serves as the regular driver, perhaps with another employee as back-up. In other cases, the bus company provides the driver as part of the deal or the employer hires the bus, complete with driver.

Subscription bus service is especially prevalent in sprawling Southern California. Many large firms, especially aerospace companies, draw employees from up to 100 miles away. Lockheed Aircraft, for example, has hired buses to bring groups of employees to its plant in Palmdale where L-1011 jumbo jets are built. One bus makes the rounds of the San Fernando Valley, where many of the employees—who used to work at Lockheed's Burbank plant—still live, 50 to 75 miles from Palmdale. Another Lockheed bus comes from Ontario, racking up 172 miles each day on the round trip.

There are estimated to be several hundred private subscription buses today in Southern California. One of the largest of these operations is COM-BUS, based in Huntington Beach. It began in 1967 when some McDonnell-Douglas employees were transferred to that city from the firm's Santa Monica plant. Employee Ron Hoffman hired a bus and learned the ropes of getting Public Utilities Commission (PUC) approval. As more employees were transferred (the Santa Monica plant was being phased out), more buses were added, until COM-BUS became a service business, developing and managing commuter bus routes for employee groups at a number of Southern California firms. It conducts employee demand surveys; establishes routes and schedules; hires late-model, luxury buses with professional drivers; selects a route coordinator from among the employees for each route to collect fares and manage its operations; assures that the necessary Certificates of Convenience and Necessity are obtained from the PUC; and handles complaints and miscellaneous business matters. Essentially, COM-BUS serves as the link between a number of charter bus companies and a growing number of employee groups.

Twelve subscription bus companies serve the United Airlines base at the San Francisco airport, carrying 1,295 of its 8,500 employees. All the companies complain about the onerous regulations imposed on their small firms by the state Public Utilities Commission—regulations intended for giants like Greyhound and Trailways.

Among the other successful subscription bus firms are the Colonial Transit Company of Fredericksburg, Virginia, and the Reston Express, of Reston, Virginia. Both provide commuter service between Washington, D. C., and its northern Virginia suburbs. And in the St. Louis area the Specialty Transit Company hauls mostly blue-collar workers from 14 communities to the huge McDonnell-Douglas plant.

A public agency in San Francisco—the Golden Gate Bridge, Highway, and Transportation District—is also operating a subscription bus service. Beginning in 1971, it has set up a number of "commute clubs" among white-collar workers in San Francisco who live in Marin and Sonoma counties. Each club determines the schedule and pickup points, collects dues, and makes a monthly subscription payment to the District. It, in turn, hires buses from charter bus companies via competitive bidding. As a public agency, however, the District does not charge a high enough price to fully cover the costs of the operation; taxpayers therefore end up subsidizing it—at several hundred dollars per bus per month.

Like car pools and van pools, subscription bus service succeeds where conventional transit fails. It gets commuters out of their cars and into an efficient, less-polluting alternative. A ridership survey on the Reston Express in 1971 showed that 21 percent of the passengers had actually reduced the number of automobiles they owned as a direct result of the subscription bus service. And another 8.4 percent said they would probably do so in the future. But its greatest advantage—except where operated by government transit districts—is that subscription bus service costs the taxpayer nothing.

A variant on subscription bus service has turned up in New York City. Some 75,000 commuters pay three times the city transit fare to ride privately owned express buses—making the 12 companies involved the joint equivalent of the fifth-largest mass transit service in the United States. The city government franchises the companies, limiting them to specific routes. Despite having to pay city, state, and federal taxes, pay for the buses themselves (no UMTA funds), and build their own depots, the private lines make money. By charging three times the regular 50 cent fare and operating on high-volume commuter runs, they can cover all their costs and still make a profit.

What attracts riders? High-quality service seems to be the key. New York Bus Line, for example, provides high-back reclining seats, individual reading lights, heating and air-conditioning that work, a seat for every rider, cleanliness, safety, and customer-oriented service—attributes similar to those of subscription buses and van pools. (The main difference between the express bus and a subscription bus is that the former makes a number of stops and accepts occasional passengers, instead of limiting itself to regular subscribers.)

Even regular metropolitan bus service can be made viable. A number of cities or districts are hiring private firms to operate their bus systems. A survey by the International City Management Association found that such contracting was occurring in only 18 cities as of 1973. But by 1978, the Urban Institute estimated that about half of the 1,023 public transit systems were being operated by private contractors.

A HELPING (PRIVATE) HAND

There is no guarantee that contract operation will bring cost savings. If the city or district insists on maintaining service on low-density routes, refuses to permit the hiring of part-time drivers to cover peak-load periods, and keeps fares at below-cost levels, the best of private firms will still be operating a money-losing system. The more operational and cost decisions placed in the contractor's hands, the greater the likelihood of reduced costs.

There are examples of private contractors who save money. The ServiCar Company in 1976 was hired by San Mateo County, California, to take over the operation of 35 buses owned by several of that county's cities. Through better utilization of its (union) labor, the firm is able to achieve a cost per vehicle hour well below that of most publicly operated systems.

Fairfax, Virginia, has had a similar experience. In 1978 it opted out of its bus service arrangement with the Washington Area Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (Metrobus). Despite the city's attempts to get Metrobus to adopt cost-cutting methods and drop lightly traveled routes, the agency had remained unmoved—but announced a cost increase for 1979, from $82,600 per year to $287,000! So Fairfax turned to Gray Line to do the job for a sliding fee ranging from $46,800 to $93,500, depending on occupancy rates. Fares on the Fairfax City Express were cut from $1.20 to $1.10, saving each commuter about $50 a year.

A major cost-cutting reform is the use of part-time drivers during rush hours, instead of paying a full day's wages to all the drivers needed to cover those three or four hours. Typically, only half as many buses are needed at midday as at rush hour. Seattle in 1978 became the first major city to negotiate a union contract permitting part-time bus drivers. As of 1979 part-time drivers had also been accepted by the transit systems of Baltimore, Washington, Charlotte, and Los Angeles.

Another way of cutting costs is to lop off the uneconomical tail ends of bus routes that generate very few passengers. One way to do this—and still provide transportation—is to replace them with paratransit. Shared-ride cabs, for example, could serve as a "collector service," feeding into heavily traveled bus routes.

One much-touted idea for improving bus service is to attract more riders by all-weather bus shelters at many of the bus stops. A whole new industry has arisen in the last few years producing these shelters, and federal grants to install them are being urged on transit districts. But there are two, quite distinct, ways to go on bus shelters. One costs taxpayers a bundle; the other generates ongoing savings.

The costly way is the way promoted by federal grants. It calls for the agency (city, district, or whatever) to buy and install the shelters and maintain them. For a large-city system, such as the 2,000 shelters proposed for Houston, even with 80 percent federal funding, the initial cost to local taxpayers would still be $1.4 million (at a price of $3,500 per aluminum-and-plexiglass shelter). But that's only the beginning. Maintenance of each shelter averages $900 a year—to remove graffiti, repair broken panes, and keep them clean. For 2,000 shelters, that's $1.8 million a year—with no federal grants available. Total system cost for 10 years: $19.4 million.

But there is an alternative. A number of private firms are now in the business of installing, owning, and operating bus shelters. They will do the whole job at no charge—in fact, they will pay the transit agency for the privilege. Why? So they can sell advertising space on a portion of the shelters, just as the transit agency already does on its buses. Typically, such firms will pay 5 percent of all their ad revenues, while taking full responsibility for the shelters, including all maintenance. At $20 per shelter per month, a 2,000-shelter system would yield $480,000 per year. In other words, instead of spending $19.4 million over 10 years, the transit agency would be receiving $4.8 million. That's a considerable saving to the taxpayers.

Yet private bus shelters have turned out to be controversial in some cities. Chicago has refused to allow them on grounds that the advertising is an eyesore. Houston and Los Angeles officials reluctantly agreed to permit both public and private shelters to be built on a trial basis, to see how terrible the ads would really be.

All the while, cities like New York, Louisville, and St. Louis have accepted private shelters with equanimity. Bus-top Shelters, Inc.—the firm that pioneered the concept in New York and has installed 500 there—has representatives marketing the idea in about 25 other cities. A competitor, Transit Shelter Advertising, has signed up more than a dozen of Chicago's suburbs for its larger private shelters, each of which generates a royalty of about $40 a month to the city.

Thumbing its nose at such advertising revenue—when its own buses carry advertising—is the height of hypocrisy for a transit agency. Instead of "protecting" the public from private shelters, such agencies should be doing everything in their power to seek ways of generating revenues and cutting costs. Substituting private for public bus shelters is an excellent way to do both.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Developing a free and responsive market in transit services is the key to ending the drain of tax money into uneconomical bus or rail networks. Frequently, however, both local and state laws and regulations are major barriers to the development of such a market. Knoxville, Tennessee's Department of Public Transportation Services (DOPTS) provides a good example of how a city can cut through such barriers. The innovative concept involves seeking and encouraging diverse forms of transportation, then helping match up riders with services.

The idea had its genesis at the University of Tennessee's Transportation Center. Dr. Frank Davis of the Center had long contended that the traditional hostility of public transit operators to competition from the private sector was a major obstacle to improving urban mobility. Davis's view was that public and private operators must work together to expand the market for all forms of transit. Instead of throwing up barriers, public officials must work to remove them.

This unconventional view got a chance to prove itself in 1975. That year, city officials met with Center personnel to devise a way out of their public transit mess. The local bus line, taken over by the city in 1967, was losing over $1 million a year because of continually declining ridership and doubled operating costs. Even at rush hour, only half the seats on the buses were filled.

The Center and the city put together a proposal to set up an agency—DOPTS—to act as a "ride-sharing broker" that would try to match supply and demand. Rather than focusing on convincing more people to ride the fixed-route bus system, it would begin with individual consumer needs and seek whatever forms of paratransit would best meet them.

One of the new agency's first steps was to make an inventory of all potential transportation suppliers in Knoxville. The results surprised nearly everyone. Including charter bus and school bus companies, taxis, limousines, and church buses, there were 770 vehicles (only 80 of which belonged to the public bus line) with 27,671 seats (only 3,600 of them on city buses). Clearly, Knoxville had considerable untapped transit potential.

The next step was to defuse the fears of existing transit operators that the project would shift riders away from their services to other forms of transportation. The project's potential to expand total ridership (by luring more people out of their cars) was stressed, and most operators proved willing to give it a try.

Once under way in 1976, DOPTS moved quickly to stimulate the introduction of subscription buses and van pools. DOPTS and the university successfully lobbied the state legislature to exempt private car and van pools from common-carrier licensing and regulation. They also lobbied the insurance companies so that van-pool drivers would not have to bear liability for all passengers. Finally, they convinced local lenders to treat van-pool loans to would-be drivers as business rather than personal loans, to enable 100 percent financing.

What has the Knoxville experiment accomplished? In its first 21 months, DOPTS stimulated the creation of car pools carrying 1,000 people and van pools carrying another 600. Another 1,200 people were using new city and private-subscription bus service. Several of the private bus firms have expanded, one going from 2 to 13 buses. DOPTS has also persuaded the city to legalize ride-sharing in taxis and is experimenting with shared-ride cabs as a feeder to the city bus line.

The Transportation Center estimates that, as a result of these activities, about 2,000 cars have been removed from Knoxville's streets, thus reducing both congestion and pollution. Ridership in subscription buses and van pools already totals one-fourth that of the city bus line (which has also increased its ridership).

The Knoxville experience is being duplicated in Southern California by Commuter Computer, a joint public/private project. In addition to promoting private car pooling by computer-matching potential ride-sharers and promoting van pooling, it recently helped the Los Angeles taxi industry introduce shared-ride service—despite a city ordinance prohibiting cab companies from "forming taxi pools." Commuter Computer pointed out that the law didn't prohibit riders from joining a taxi pool. So it has now launched "Come Together" ride-sharing, in which it is helping riders form taxi pools.

The transit brokerage concept is a low-cost, effective way to improve urban transportation. By stimulating the private market, it expands the supply of unsubsidized transit. Moreover, unlike the case of costly new subways like BART which attract mostly bus riders, these new paratransit options succeed in luring commuters from their cars. Besides giving taxpayers a break, they accomplish the elusive goals of reducing both congestion and pollution.

Robert W. Poole, Jr. is the editor of REASON. This article is adapted from Mr. Poole's new book, Cutting Back City Hall, published in May by Universe Books. Copyright ©1980 by Robert W. Poole, Jr.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Alternative Transit."

Show Comments (0)