Make the IRS Your Partner

How the average person can use real estate to shelter his income from taxes.

Every year around April 15 you hear complaints that "few rich people pay any tax," that "the tax burden in the United States is carried by the beleaguered middle class." And a common assumption is that the people who get away with paying little or no tax are doing something fraudulent, or at least questionable under the often-ambiguous tax laws. But doesn't it make sense that, since they are so spotlighted in the public eye, the IRS would scrutinize their tax returns a whole lot quicker and in greater detail than yours or mine? In fact, their paperwork is in much better shape than 90 percent of taxpayer submissions.

Well, if they're not cheating, what's the super secret of paying practically nothing, while so many of us wind up with a sizable "contribution" every year? The biggest secret is that there is no super secret. You and I can enjoy the very same advantages. The games the big boys play are open to all of us—but it does require getting into position to be able, like them, to deduct those investment tax credits, depreciation, and a whole host of associated write-offs. And you do it by making the IRS your partner, by holding on to the earnings that are now going to pay your income tax and using them instead to increase your own personal fortune.

The sound business practice involved here is to leverage your equity position through maximum borrowing, which carries an element of risk. Depending upon when you were born, or just how much "remember the depression" philosophy your parents may have showered upon you, this could cut across your grain of thinking. But to get an economic leg up on inflation, you must become a part of our free-enterprise system. To accomplish this feat, to join the group, you will need to pay for your ticket on the way in. There are only three legitimate ways to acquire these means: earn and accumulate it (the depression-era legacy), inherit it (the lucky way), or borrow it (and that's what we're talking about here).

A PENNY SAVED

Never having had much and consequently being very naive in financial matters, most of us have approached money on an ultraconservative basis—like saving money in the bank. If government regulation were consistent, banks, like the cigarette companies, would have to print on your statement, "Banking is dangerous to your financial health," as the five to eight percent you think you are making is really "bottom lining" at a considerable loss because of inflation. A lot of us consider our home our prime investment and inflation hedger, and that's a good basic choice.

The problem here is that we also dream about the day we'll have the mortgage paid off, and that's not too smart. If that's your plan, you're overlooking a big chance to get ahead and stay there by leveraging your equity into a free-enterprise venture. Such a venture doesn't have to be a change in your career or a brand-new business; it can be something you are already familiar with. Let's take a typical "oh so true" example and see what we can do with it. How many people do you know like…?

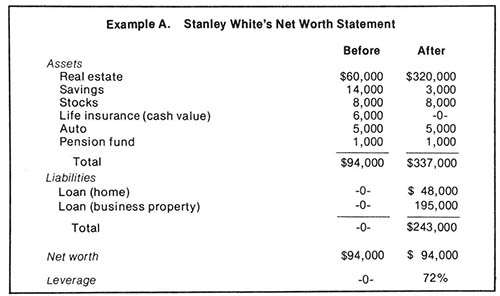

Stanley White is 49 years old, married, two kids, one of them still in college. The Whites bought a tract house in the early '50s for $10,000, with $1,000 down—$500 of which they borrowed from his folks—on a 25-year loan. They've lived there ever since and are quite proud of the fact the mortgage was paid off two years ago. On today's market, the house is worth $60,000+ (would you believe it?). Stanley also has $14,000 of savings in the bank, another $8,000 in company stock (which is about 20 percent less than the average price he paid for it), a $10,000 life insurance policy with a cash value of $6,000, a fairly new car valued at about $5,000, and $1,000 vested interest in the company's new retirement plan. Sound pretty good?

Stanley's salary is now $28,000 a year—quite a ways up from the $4,800 he started with 25 years ago. The Whites live in a state that doesn't have an income tax; their federal tax base is 25 percent, taken out of the paycheck in advance ($7,000, not counting Social Security). Through the years they have learned to live quite modestly and are comfortable and happy with the way they have managed things. Everything here seems okay…on the surface.

Stanley will work 16 more years until he's 65. Let's give the Whites the benefit of the doubt and say that they can save $2,000 a year, even with today's soaring prices. This should give them over $50,000 in the bank by that time, but with meager bank rates and his 25 percent tax on the interest, plus inflation and the consequent loss, they will have a buying power—even with a conservative 4.5 percent inflation rate—of less than $25,000. Conversely, the Whites' home will ride with inflation, maybe be worth $90,000 or more. But can they afford to sell it? Wouldn't the cost of replacement be equal to what they sold?

Contrary to the naive belief that when we retire we're all ready to change our lifestyles and slink off to a cave on Social Security, Stanley will want to vacation and do all the things he has yearned for but never had the time to do. Won't this require even a bigger monthly budget? Where's it going to come from? The Whites will dissipate their savings very quickly just supplementing Social Security income. They're in a box and not even aware of it.

BORROWING POWER

There doesn't have to be a sad end to this story, because Stanley has equity. True, it's not doing him any good, but if he leveraged it, it could do him a whole lot of good. First off, we mortgage his house at as much leverage as we can get, probably 80 percent of market value, giving Stanley $48,000 in cash and …what's that?—"a mortgage payment of $_____ per month that he didn't have before"? True, but just wait. Next, we borrow the cash value on his life insurance policy ($6,000). Why? Because we would borrow even if we didn't need the money, as an after-the-fact attempt to partially retrieve a very poor investment.*

So now, between the house and the insurance, we've gathered up $54,000 worth of leverage for old Stanley. We'll leave his stocks and retirement fund alone—we don't need it, and every man is entitled to his dreams, even if they don't materialize. We will take, however, $11,000 of the $14,000 in the bank, leaving $3,000 for emergencies or to start a Keough (tax-deferred) retirement plan under Mrs. White's name. This gives us $65,000 of hard-cash leverage to work with. We use it as cash down payment, leveraged at 75 percent, on a good commercial building or an apartment building or a combination of duplexes and triplexes or four more residential houses. Now our Stanley is the proud owner of combined real estate valued at $320,000, a real honest-to-goodness American entrepreneur. To see how all this looks on a "before and after" net worth statement, see Example A.

We won't really expect our new acquisitions to produce a net addition to income. We just want them to pay for themselves—discharge their debt, taxes, insurance, etc. But what about Stanley's new payments on his own home? If he isn't earning anything on the new investment, where does he get the money to make those payments? Why, from his partner, the IRS—with some of the $7,000 he was paying in income taxes. "Uncle" is now helping him to become his own man within the free-enterprise system.

Here's how it works. Remember that we've assumed that Stanley collects rents from his new business property that just cover his interest on the $195,000 loan, as well as taxes, insurance, maintenance costs, and so on. So for income tax purposes, his new business income will be offset by his new "out-of-pocket" business expenses. But he will also have the decided advantage of being able to depreciate his newly acquired business property—that is, to claim the depreciation as an expense. This, in turn, will mean that the business will now show a loss (but remember, there's no added cash outlay involved), and this loss will be used to offset taxable income from Stanley's job.

For example, say the property we've bought for $260,000 has improvements worth $170,000. The land, which accounts for the other $90,000, cannot be depreciated because it's always there, does not deteriorate like a structure, and, in fact, is the one thing that increases the overall value of your investment, especially during times of inflation. The $170,000 building can be depreciated on an established schedule, using the "straight-line method," at $8,500 per year for 20 years, or the period can even be shortened to 15 years, at $11,333 per year, if he needs more protection. Other methods available—"double declining balance" or "sum of the digits"—would allow for depreciating a whole bunch now and then less downstream, instead of the same amount each year.

This means that Stanley shows a loss of at least $8,500 on his business Schedule C (of his federal income tax form). When this is transferred to the appropriate line on his 1040 submission, it will serve to reduce his overall taxable income accordingly. In addition, there is a 10 percent investment tax credit that he may use (one time only) in any given year. Plus, with the mortgage on his own home, he now has interest payments to add to his itemized personal deductions.

So you can see how advantageous is depreciation as a tax avoidance vehicle. This is why an individual who has owned a piece of property over a long period of time, and has depreciated it to or close to a "book value" of zero, may well elect to exchange it for another property of similar value, just to start this depreciation process all over again and, by exchanging, to defer taxes on the capital gain.

Sixteen years from now, Stanley's home might be worth over $90,000, and if we believe that (and we should), his combined real estate will be worth over a half-million and will be two-thirds paid for. And it all happened without changing his lifestyle one bit!

TAX-AWARE INVESTING

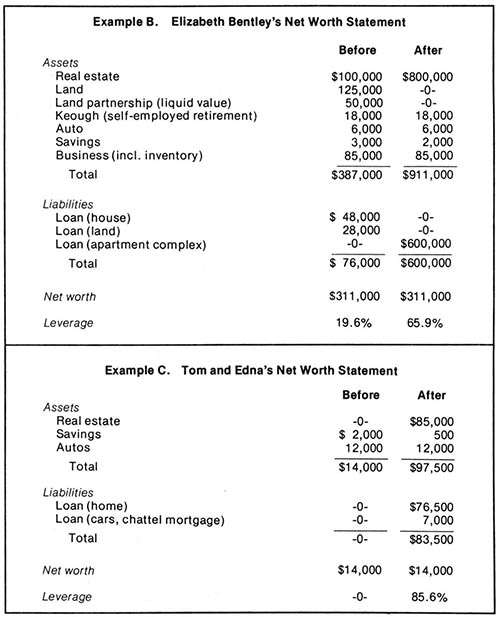

Elizabeth (Betty) Bentley was and is a liberated woman. She set out quite early in life to provide for herself, so she purchased a home and has made investments in land from time to time. She has owned and managed a very prosperous antique and gift business for the past 20 years and would like to expand it, but despite all honest effort with personal and business deductions, she cannot get her net income below $24,000 and a 40 percent bracket. "If I make more money, my income taxes will go up even further, and I just can't see working for nothing."

The problem here is that Betty's investments, though admirable, were the wrong kind for her. The land buy is unimproved and offers no (much-needed) advantages of depreciation. Her "deferred tax" land partnership is self-contained, most of its profits eaten up by administrative costs over which she has no control, and it does not afford tax relief now when she needs it. Obviously, we need to get rid of the land, the land partnership, and her house for that matter—she only bought that big place for the tax and interest write-offs.

But if we sell, Betty will be exposed to a large capital gain because she bought the house and land some time ago and has a large potential profit in both. So what we're going to do is use the equity in this property for a leveraged trade upward, like a big apartment complex, and defer all such taxation until she dies, or "forever," as Betty likes to put it. The land partnership lacks liquidity, and even though they say it's worth $60,000, we'll have to discount it to $50,000 (what she paid for it) and be glad to get rid of the damned thing.

Okay, now that we know what we want to do, let's see how much "leveraging power" we can scrape up out of Betty's assets. The house has a value of $100,000—she owes $48,000, so that's $52,000 equity. The land's value is $125,000, with $28,000 owed; that's another $97,000. We said we would sell the land partnership for $50,000 cash (no profit), so all in all we've amassed $199,000. Let's take $1,000 out of her bank account and make it an even $200,000. We can leverage this into at least an $800,000 deal. That's a whole bunch of apartments, and Betty never dreamed she would be in control of that much money! To get a better picture, see what this looks like on paper in Example B.

Betty moves into an apartment in her complex, just right for her. She now has enough depreciation to more than offset income from her business, and now she can expand into yet another location like she wanted to. Where does the money come from? She borrows against her business, which is zero-leveraged.

COMING UP WITH EQUITY

As our last example, we have Tom and Edna, that delightfully young and carefree couple down the block. He's an engineer and she is a supervisor with the telephone company—both excellent jobs, producing a combined gross income of over $39,000 a year. Although there is a more than $3,200 cash flow passing through their fingers each month, they don't seem to be putting any of it aside. Tom and Edna live high and fast, and other than about $2,000 in the bank and $12,000 worth of sports cars, they're broke! "After six years of marriage, we don't have a damned thing to show for it. What we don't blow, we pay out in income taxes."

They seek expert advice, and it's pointed out that one step in the right direction would be to at least acquire a house for investment appreciation but, more than that, for interest and property tax write-offs. Where are they going to get the money for the down payment? Since they have every credit card imaginable, between personal loans there and perhaps against the cars, this poses no problem. They certainly can make any kind of payments with all their cash flow—kind of like a forced savings they both agree they need.

Tom, however, has a much better idea. Money is very tight right now, 18 percent and up when you can get it. Maybe the best move is to approach a seller directly on a contract or installment sale. By offering a little more than the seller hoped to get for the property, they may arrange 10 percent down instead of 20. It's a good deal for Tom and Edna as well as a good move for the seller when it comes to capital gains taxes. They decide to chattel mortgage the cars for the small amount of cash they'll need. (See Example C.)

Tom and Edna now have payment obligations (mortgage plus car loan) exceeding their previous rent. And since you can't depreciate a home like you can business property, they won't have that tax advantage. But their partner, the IRS, will still be helping them out; Tom and Edna can deduct interest payments on both the mortgage and the car loan, reducing their federal and state taxes by more than enough to offset the increased cash outlay. Could they have swung a duplex and come out even better? Probably so.

GET MONEY TO MAKE MONEY

Our lessons learned are these: it takes money to make money; if you don't use it, you'll lose it; it's not how much you make, but what you get to keep that counts. Old adages? To be sure, but all with a grain of truth.

The middle- and lower-income people in this country do carry the major burden of the tax load. They never seem to be able to acquire the necessary leverage of equity to avoid taxes or are psychologically stunted in their financial thinking, causing frugal plodding-along reactions and losing ground every step of the way. Not to borrow money is not a thing to admire! The way you make money is to use someone else's. This is common business practice; all businesses (worth their salt) have borrowed since the dawn of time. To wait to save it is a nonsensical waste of both time and opportunity. Leverage and more leverage is the secret of success.

You don't have to leverage into real estate as our examples have illustrated. You can opt to be "born again free" and use the money for that business of your very own that you've always wanted, to seek and gain direct rewards from the benefit of your capabilities, rather than continue to be a pawn in the system that sometimes reeks of unfairness. Businesses enjoy all the write-off advantages of real estate and quite a few more. Then too, they have a greater span of accelerated profit potential—that is, you don't have to sit and wait for appreciation in value through inflation; you can get out and do something about the situation yourself. The same would be true of static versus dynamic income possibilities.

Whether you're a Stanley White, a Betty Bentley, or a Tom and Edna—or whether you don't fit one of those prototypes—the important thing to remember is that there exists for you an opportunity to take money you already have or will have. That money is slated now for income tax payments, but you can turn around, and with the IRS as your partner, invest in your future.

Robert Haisman is a business broker and a consultant specializing in tax loopholes for small businesses. He is the author of Be Free: Happiness Is Owning Your Own Business.

* An insurance policy buys only one thing—an estate, if you die too soon. Any bill of goods you've been sold that overpayment of premium (whenever there is cash value) constitutes a decent return on investment is pure "horse pucky" out of the depression years. But once you've made the mistake, you can salvage something by "arbitrage." Since the insurance company pays you about 3 percent on your overpayment, they are more than happy to let you borrow your own money back at 6 percent. You, in turn, can certainly place this money today at 8 to 10 percent interest, making several percentage points on the deal (arbitrage). Could you have circumvented the middle man in the first place? Sure; you could have bought the cheapest term insurance policy you could lay your hands on.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Make the IRS Your Partner."

Show Comments (0)