How to Perpetuate Poverty

If you want to keep poor people in their place, just do what the welfare system does.

Suppose someone wanted to design a government program that would perpetuate poverty in the United States while ostensibly spending billions of dollars for its elimination. How would they go about doing it?

First off, they would want to make sure that no one understood what they were up to. A good way would be to proclaim that the true goal of the program was to eliminate poverty rather than perpetuate it. Not only would this confuse the issue, but it would ensure that anyone who criticized the program would be accused of being against the poor!

As to implementing the real objective, a good move would be to create strong disincentives and barriers to prevent poor people from being able to work and improve themselves. This could be done by imposing high tax rates on the incomes of poor people, establishing high minimum-wage requirements, encouraging the growth of labor unions, and passing numerous licensing laws and other regulations to make it more difficult to gain employment or start a business.

It would also help if the system encouraged cheating, led to the breakup of families, and required a huge bureaucracy to administer it (so that lots of nonpoor people would have a vested interest in the system). And, as a final fillip, poverty should be so defined that the official statistics would always show the situation getting worse, no matter how much money was spent to alleviate it.

If all this were done, you would have a sure-fire means of perpetuating poverty. You would also have constructed a duplicate of the welfare system in the United States.

TO WORK OR NOT TO WORK

Let's start with incentives. Presumably, a welfare system that actually had as its goal the elimination of poverty would be constructed so as to help and encourage people to get jobs and improve themselves. The US welfare system, however, does the opposite. It uses a so-called means test for welfare benefits, which takes away those benefits if someone on welfare earns any income. The effect is exactly the same as if very high tax rates were imposed on welfare recipients.

Not surprisingly welfare recipients react to this set-up the same way high-income people react to high tax rates: they avoid earning "taxable" income. Toward this end they can either avoid work, work only for returns that are not included in the definition of income for welfare or tax purposes, or cheat. And people on welfare are just as innovative as people with high incomes when it comes to "fiddling" the system, as the British say.

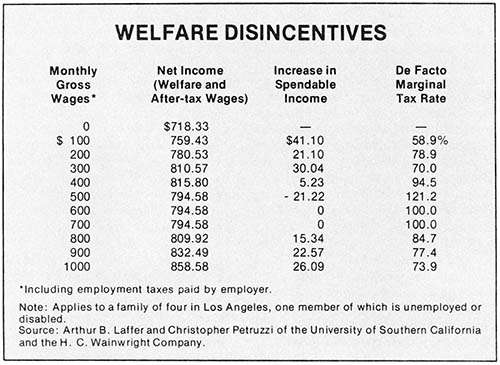

To see how the means test translates into high marginal tax rates (the tax on each additional dollar earned), suppose that a family of four living in Los Angeles in 1979 attempted to earn some money on top of welfare in order to better itself and ultimately get off welfare altogether. If this family were receiving all the benefits to which it was entitled by law, its welfare income would amount to about $718.33 per month. But each dollar earned on top of this would reduce part of these benefits. So if the family earned $100 per month on top of welfare, its disposable monthly income would not increase by $100. Because taxes must be paid on that $100 and because some welfare benefits are reduced, this family's spendable monthly income would only rise to $759.43—an increase of $41.10. This translates into an effective marginal tax rate of 58.9 percent on that $100 of gross income.

This would be bad enough, but the system gets worse. Suppose this same family reached a point where it was making $400 per month in gross income on top of welfare. Its spendable monthly income would only increase to $815.80 per month—a mere $97.47 more than it would have under welfare alone. This translates into better than a 75 percent average tax rate on the family's earned income. And the marginal tax rate is even higher.

If this family were to add another $300 per month, bringing its gross earned income up to $700, its spendable income would actually drop! From the $815.80 the family had to spend while earning $400 in addition to welfare, its spendable income would drop to $794.58 if it earned $700 in addition to welfare. In other words, the actual taxes that must be paid, combined with a reduction in welfare benefits, has imposed an effective marginal tax rate in excess of 100 percent on this poor family.

MAXIMIZING INCOME

An examination of the figures for this Los Angeles family (see box) shows how the welfare system conspires to impose confiscatory tax rates on the poorest members of society, thus robbing them of any incentive to improve themselves and ultimately get off welfare. These effects are not exceptional. Similarly high tax rates exist throughout the spectrum of welfare benefits wherever there is a means test. For example, it is estimated that effective marginal tax rates for people on Social Security resulting from the earnings limitation may go as high as 79.1 percent (see the Congressional Record, June 27, 1979, p. S 8608).

Although the amount of benefits lost for each dollar of income varies from program to program, the effective tax rates add up because so many people qualify for more than one program. This is why the effective tax rate on earned income can easily exceed 100 percent for a family on welfare. Is it any wonder, therefore, that so few welfare families make the effort to earn money to supplement welfare? They may not be lazy, as so many conservatives are fond of alleging; it is much more likely that they are simply responding to the economic disincentives.

Of course, welfare families can and do find ways to increase their spendable incomes within the constraints of the system, just as rich people use tax shelters. One easy way for the family to improve itself is for the father to "abandon" his family by leaving home. This action will immediately increase the family's spendable income.

Consider a family of four living in Michigan whose father is employed at the minimum wage. His net earnings of $4,504 per year are supplemented by the Earned Income Tax Credit and food stamps for a total disposable income of $5,678. If the father leaves his family, however, the diminished family will be entitled to a basic AFDC (Aid for Families with Dependent Children) grant of $4,896. This will be supplemented by food stamps and Medicaid benefits, for a total income of $7,161—a gain of $1,483. But if the father continues to work—away from the family and the eyes of the welfare workers—the total increase in income to the group goes up to $5,987. In this manner the welfare system encourages family dissolution.

To prevent welfare recipients from cheating like this requires a Gestapo-like reporting system in which thousands of caseworkers must constantly check up on welfare recipients to ensure that they are not fiddling the system or earning unreported income. More than 100,000 caseworkers are employed by the federal government just to determine what is income for welfare recipients and what is not.

LOWER THE TAX RATES?

A solution to the problem of high tax rates on welfare recipients would be to take away less of each dollar that is earned. Unfortunately, this would mean extending benefits upward to families with relatively high incomes. It is estimated that if each family of four were to receive a basic income of $6,000 and lose only an average of 25 percent of each dollar earned above this level, then the "break-even" point would be an annual income of $24,000. Under such a system there would certainly be an increase in the incentive for welfare recipients to earn income, but more than two-thirds of all American families would qualify for some sort of cash payment.

Former secretary of HEW Joseph Califano commented on this dilemma during testimony regarding President Carter's welfare reform plan:

The system of "benefit reduction rates" is designed to address a fundamental problem: if cash benefits are reduced at too steep a rate as earnings increase there will be no incentive for work.

For example, if the cash benefit is reduced by $1 for every $1 earned, there is obviously no work incentive whatsoever.

If the cash grant is reduced 90 cents for every $1 earned, there may be no incentive, because travel costs and other expenses of going to work will mean there is still little or no real improvement in the individual's financial condition as the result of employment.

But, there is also a problem at the other extreme. If the cash benefit is reduced only 25 cents for every $1 earned, there is a good incentive to work, but families will continue to receive cash assistance at income levels that seem too high to many taxpayers.

The upshot is that there are only two ways to encourage welfare recipients to work: either cut benefits, or increase them to include those with higher incomes. There is not much middle ground that can be carved out of this, and obviously there are great political obstacles to either approach.

DISCOURAGING WORK

One alternative that has received the most attention in recent years is the guaranteed minimum wage, or negative income tax, approach. The idea is simply to place under everyone an income floor that would ensure a minimum standard of living and nothing more.

The problem, unfortunately, is that unskilled workers seem to prefer staying on welfare even if the marginal tax barriers do not exist. This showed up in the so-called Seattle-Denver income-maintenance experiment, as reported by its director, Robert Spiegelman, in testimony before Senator Moynihan's welfare subcommittee.

According to Spiegelman, the experiment showed the following results:

• People worked less in general. A minimum-income program guaranteeing all needy families support at 100 percent of the poverty line ($6,200 for a family of four), and reducing the welfare benefit by 50 cents for each dollar earned if the recipient worked, would result in husbands in welfare families working 6.2 percent fewer hours, wives 22.7 percent fewer, and female heads of families 12 percent fewer. And such a program on a national scale would cost some $40 billion more than the present system.

• Minorities tended to work even less. On a long-range basis, white husbands worked 96 hours less per year than if they weren't given a guaranteed income, black husbands worked 230 hours less, and Hispanic husbands 204 hours less.

There are several possible explanations for these results—that workers face opportunities so dismal that they prefer staying on welfare, for example, or that such other factors as minimum wage laws keep potential employers from offering work to the unskilled. But whatever the explanation, the experiment does not show a minimum-income program alone achieving the desired results. In addition, the system encouraged family breakups. White families suffered breakups 18 to 63 percent more frequently than a control group, black families 15 to 73 percent more, and Hispanics had a 37 percent greater incidence of family breakups.

It would seem, therefore, that the guaranteed income is not a satisfactory alternative to the present system.

WHAT NEXT?

An innovative solution to the present welfare mess has been proposed by Cong. David Stockman of Michigan. He recommends that means-tested welfare be abolished altogether, to be replaced by a universal system of child payments, on the theory that child support is the fundamental basis for the welfare system. This would be combined with a modified negative income tax and an end to the minimum wage. Such a program would encourage employers to hire workers at low wages while ensuring an adequate income for the worker. Presumably, as the worker's skills increased his income would improve, and the income support could be safely phased out without penalizing the worker.

A more radical solution still would be to abolish cash welfare payments altogether and supply only in-kind benefits. In other words, give the poor the actual food, clothing, and shelter, but no money. Interestingly, this was proposed recently by former New York State social services commissioner Philip Toia.

Toia would have the present New York State welfare replaced with a "soup-line" and all other welfare programs turned over to voluntary agencies whose functions have been usurped over the years by government. "State and local governments simply can no longer afford to pay for the range of services we've been providing for the past decade," Toia said. "It's time we gave a majority of the provisions of those services back to the nonprofit agencies created to serve the clientele on our welfare rolls."

Of course, Toia is only talking about state-administered welfare programs, not federal. But the idea is to voluntarize the welfare system as much as possible by giving back to private welfare agencies the functions they served in the past and providing only what is needed for actual survival.

Perhaps the tax revolt will force people to go as far as Toia to reform the welfare system. Some kind of reform is clearly in order. According to the Commerce Department, US governments spent $209 billion on welfare in 1977. With a broader definition of welfare spending, William Lawrence of the Institute for Socioeconomic Studies put the actual figure at closer to $250 billion.

But even the $209 billion would provide an income of $6,200 per year (defined as the poverty level by the Census bureau) for 33 million families, or more than 130 million people! Yet the Census Bureau reported that 24.7 million people remained below the poverty level in 1977. Obviously, something is wrong here.

Waste, fraud, and incompetence are the usual explanations for the failure of the welfare system to eliminate poverty. A more interesting explanation is that the Census Bureau, which officially measures the number of people living in poverty, defines poverty in such a way that it can never be eliminated. It does so by measuring poverty only on the basis of money income, excluding all in-kind benefits such as food stamps, medicare, and housing subsidies. Yet the income that is excluded is certainly very real. The Congressional Budget Office recently attempted to make the Census figures more realistic by including in-kind benefits. The conclusion? The Census Bureau had overestimated the number of people living in poverty by more than 50 percent.

Of course, 12 million people living in poverty is still a lot of people, but the magnitude of the problem—and therefore its solution—is greatly altered by the revised data. Spending more money is obviously not the solution to poverty, and the current political climate fostered by Proposition 13 probably makes it impossible anyway. The ultimate solution to poverty and the failure of the welfare system is to find ways to help people help themselves.

TRY AN ECONOMIC BOOM

What if we abolished government welfare altogether—along with barriers to employment such as minimum-wage laws? The effect of such a move would not be nearly as disastrous to the poor as most people would believe, because a substantial number of people on welfare are already employed in the so-called subterranean economy. According to economist Peter M. Gutmann, more than $200 billion per year is generated by the subterranean economy, unreported by economic statistics. Taking this into consideration would substantially reduce the official unemployment rate.

Elimination of the minimum wage and tax and regulatory barriers to employment, plus a general reduction in all taxation made possible by eliminating welfare expenditures from the budget, would probably result in such an economic boom that our principal problem would be a shortage of workers, not unemployment. Those who are truly indigent could be easily taken care of by private relief agencies.

Barring an elimination of all government welfare, it would be preferable to at least get rid of federal welfare programs (along with the federal minimum-wage law and federal taxes and regulations that discourage employment) and allow state and local governments to handle the problem. The closer government is to the people, the more likely it is that its policies will be geared to the specific problem. At the local level, moreover, it would be preferable to adopt something along the lines of an in-kind welfare program, such as the one suggested by Philip Toia (which unfortunately has not been taken up by the political powers that be). If this were done, the cost of welfare would drop to almost nothing.

The failure of the present welfare system in the United States is now so obvious that some major overhaul of it is essential. It is possible to improve the lot of the poor while reducing the cost of helping them. But that, of course, takes a desire to eliminate poverty, not to perpetuate it.

Bruce Bartlett is a Washington-based writer and political consultant, currently a congressional staff member.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "How to Perpetuate Poverty."

Hide Comments (0)

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mute this user?

Ban this user?

Un-ban this user?

Nuke this user?

Un-nuke this user?

Flag this comment?

Un-flag this comment?