Trends

Which Airlines Violate Safety Rules

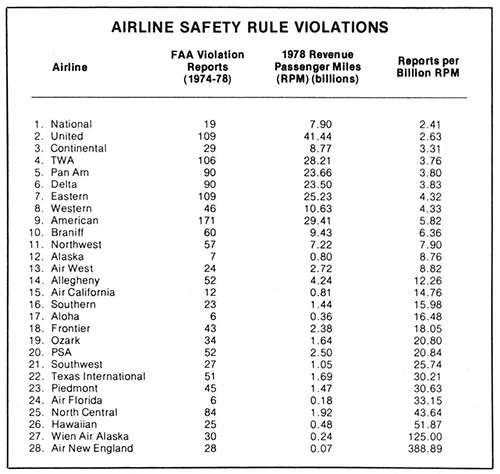

As pointed out in these pages earlier this year (see "Is This Any Way to Run an Airway?" January 1979), the Federal Aviation Administration is loathe to give out any information by which aviation consumers can make their own safety decisions. Nevertheless, such information does exist, and REASON has managed to obtain some of it. Hidden away in an obscure report entitled "Air Carrier Enforcement History, Jan. 1974 - Jan. 1979" are page after page of computer printout itemizing, for every airline, the specific known violations of Federal Air Regulations on which the FAA has taken final action. To help prevent comparisons, the agency has conveniently failed to add up any totals or present any summaries. But a few hours with a pocket calculator produced the totals listed in the accompanying table. Since airlines vary greatly in size, it would be meaningless to compare directly the number of violation reports. Instead, the data have been "normalized" by dividing the number of reports by the number of 1978 revenue passenger miles flown by each airline.

What can we conclude? To begin with, the figures include only violations which came to the FAA'S attention and on which they took action. Some are relatively trivial (e.g., stowing a TV set in an unapproved location) but many are quite serious—operating with defective equipment, failure of pilots to follow air traffic control procedures, etc. Since the violations cover a four-year period, the mix of serious and trivial among airlines tends to even out. To be sure, an airline with 30 percent more violations is not necessarily 30 percent more hazardous to fly—but differences of several hundred percent (as between, say, United and Air West) are probably significant.

From the table we can see that, in general, the 11 major trunk airlines follow the rules more carefully than the others, nailing down the top 11 slots. But even here the worst (Northwest) has 3.3 times as high a violation rate as the best (National). The differences are far more pronounced when we compare regional airlines: for example, note that North Central has five times as high a violation rate as Alaska Airlines does.

So far, we haven't been able to obtain actual accident data broken down by airline from the FAA. But since accidents are such relatively infrequent events, it's not clear, statistically, if such data would be a usable indicator of relative risk. For the time being, the adjacent data on air safety violations appear to be at least one factor worth taking into account in making your air travel decisions. With deregulation opening up most routes to significant competition, you will more and more often face a choice of airlines. When that's the case, if one carrier has a significantly lower violation rate than the other(s), you may wish to make it your choice.

Energy Boondoggles under Attack

Scarcely a week goes by without a new attack on the major elements of the Carter administration's energy program—an oil "windfall profits" tax, a synthetic fuels crash program, and continued price and production controls administered by the Department of Energy.

Some of the most stringent attacks are being made on the synfuels boondoggle. Energy Future, the report of the Energy Project at the Harvard Business School, throws cold water on the idea of a massive synfuels program. Project team member Mel Horwitch recently told a Senate subcommittee that among the risks of such a program are "inefficient use of funds, hazards to the environment, and, ironically, a future wholesale disillusionment with the synthetic fuels option as a result of a possible backlash…as it becomes clear that the grandiose promises we hear today will not be met."

These views are echoed in a new Resources for the Future study, Energy in America's Future, released in September. That report stresses the need to subject new energy technologies to the test of the marketplace and emphasizes the benefits of free-market energy pricing. Representatives of both Resources for the Future and the Harvard project suggest that it would be far more prudent to experiment with various synfuel approaches than to rush into a huge production program.

Strong opposition to the synfuels crash program is also being heard from environmental groups, who fear massive new pollution problems, especially if Carter's request for a federal agency to override environmental regulations were also approved. A number of these groups—among them the Conservation Foundation, the Sierra Club, the League of Women Voters, and the National Resources Defense Council—now endorse price decontrol as a key means of promoting energy conservation. Here and there these pleas are being heard—witness Carter's decontrol of heavy-oil pricing and the recently proposed 50 percent boost in the price of natural gas derived from tight sands.

The proposed "windfall profits" tax has come under blistering attack from Sen. Mike Gravel. In a recent paper Gravel claims that the measure is really an excise tax, "simply a revenue measure—a way to help…balance the budget at the expense of an unpopular industry." Gravel calls Carter's treatment of the energy industry "demagoguery" and says these policies are moving us toward nationalization. He also warns that the withdrawal by the tax of over $100 billion from the nation's private investment pool could trigger a depression.

DOE regulations are coming under new fire. The Washington Post recently quoted an unnamed DOE official who, faced with testimony that independent oil firms are being destroyed by the regulations, admitted, "That's true.…the only answer is to get rid of these regulations. There is no way they can work. They don't protect consumers and they never have." B.J. Goffney, vice-president of Highway Oil, said flatly, "DOE should get out of the regulation business. The regulations are a shambles. The system is beyond repair and not worth the time of day." Goffney's testimony came just a week after the Office of Management and Budget issued a report criticizing DOE for hastily issuing poorly analyzed regulations that have grown into a tangled, confused, and error-filled mess.

The idea of abolishing DOE altogether is beginning to be heard more often these days. Dr. Michael K. Evans, president of Evans Econometrics in Washington, in July called for scrapping the agency. And in September Louisiana Gov. Edwin Edwards made the same recommendation on CBS-TV's "60 Minutes."

And now the role of the feds in creating the energy crisis has been acknowledged in federal court. Earlier this year the International Association of Machinists had brought a price-fixing suit against the OPEC governments. On August 13 US District Court Judge Andrew Hauk ruled against the IAM but delayed releasing his decision until September 22. Judge Hauk dismissed the suit on grounds that it was the US government, not OPEC, that was principally to blame for the energy crisis. "The federal executive branch has helped to create the energy crisis, has helped to intensify this crisis, and has utterly failed to resolve it," he wrote. The DOE "stepped in to turn a small shortage into a large and horrendous shortage. The result was excessive price increases and long lines at domestic service stations."

What if the government had stayed out? That question was answered by a Mellon Institute study released in September. Authored by Roger W. Sant, a former top US energy official, the study concludes that a free-market (or "least-cost") energy strategy might have saved the country $43 billion last year. Sant said his eight-month computer study shows that fostering competition among diverse technologies can resolve the national energy problem. Had this approach been in use last year, every man, woman, and child in America would have been $200 richer, according to Sant's calculations.

Agencies Ease Regulations

Experienced bureaucrats have finely honed survival skills. And those heading federal regulatory agencies have some of the best. Thus, in the current mood of deregulation, many agency heads have decided that the best way to survive is to make some deregulatory concessions. By easing their most burdensome regulations, they can reduce the motivation of those most affected to continue pushing for complete deregulation.

Examples of this practice abound. In recent weeks we have observed the following:

• The Interstate Commerce Commission is proposing to allow railroads to raise or cut rates by seven percent a year with little ICC control. (Under the 1976 4-R Act, such rate changes require a railroad to prove it does not exert "market dominance.") The ICC is also considering easing present restrictions on truck routing, to save fuel.

• The Environmental Protection Agency has withdrawn "unreasonably stringent" clean-water regulations for 64 industry groups, saving them up to $200 million. The rule change substitutes "best conventional technology" for "best available technology" for certain pollutants. In most cases the more stringent rules would have increased clean-up effectiveness by only a few percent—at large cost.

• The EPA has also decided to waive requirements for some 1981 cars that would have sharply reduced carbon monoxide emissions. The waivers, based on requests showing that compliance is not practical by then for certain models, will apply to 20 percent of 1981 cars.

• The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has been ordered by Congress to exempt from OSHA job safety regulations nearly all businesses with 10 or fewer employees.

• The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms has decided that beer advertisements may refer to competing beers by name, instead of just referring to "Brand X." BATF is still considering whether to apply the same standard to ads for wine.

• The Federal Railroad Administration is revising its safety standards to eliminate "unnecessary and burdensome maintenance and inspection requirements," a move it says will save the railroads $100 million a year.

• The Federal Trade Commission has cut back a number of proposed regulations, including some that would have required funeral homes to display their lowest-price coffins instead of just listing their prices. "The less tinkering with the market, the better," said FTC Chairman Michael Pertschuk of the change.

While these changes are welcome news to those being regulated, they leave unchallenged the basic premise that government knows best and has the right to impose its judgments on buyers and sellers. Until that premise is overturned, "tinkering with the marketplace" will continue to plague us all.

Paying for Airports

Having airlines pay fees directly to airports to fund improvements is how such matters would be handled in a free market. Yet that is not how they are handled now. At present, the federal government gets into the act, charging an eight percent tax on airline tickets. The proceeds go into a federal trust fund, to be parceled out when and as the Federal Aviation Administration decides. There is no particular correlation between who pays and who benefits. Moreover, in recent years the Office of Management and Budget has been limiting the amount the trust fund can spend each year (since it shows up as part of the federal budget), leading to the accumulation of a $3 billion surplus—and the lack of needed improvements at many crowded airports.

All that would change under a bill introduced by Sen. Howard Cannon. In a significant move toward privatization, it would cut the ticket tax down to two percent, limiting the trust fund's expenditures to small airports and air-traffic-control improvements. Large airports would be left free to negotiate their own user charges with the airlines, to pay for needed improvements. This change, says Cannon, "will eliminate the cost of the middle man, reduce red tape for airport development, and speed up the implementation of needed capital improvements."

Free-market user charges would most likely fluctuate, based on demand, as recommended by economists (see "The Airport Crisis and How to Solve It," REASON, Apr. 1973). Just such a move has now been endorsed by the General Accounting Office. Citing the $800 million cost of air traffic delays in 1977, a GAO report urged that higher landing tees be charged during peak hours to motivate users to switch to less busy times. Besides saving travelers' time, such charges would also reduce the 700 million gallons of fuel wasted each year by the delays.

New Chinese Freedoms

Both personal and economic freedom seem to be on the increase in China these days. Last summer saw the introduction of a legal code for the first time since the Communist takeover. At least on paper it provides for open trials and legal counsel, prohibits extorted confessions and arbitrary arrests, and gives the judiciary some legal independence. An electoral code provides for election of county councils by secret ballot, with non-Communist candidates eligible to run.

By September Chinese citizens were taking advantage of their new freedoms. "Democracy Wall" in Beijing was back in action, and the underground journals Explorations and April 5 Forum reappeared on the streets. Some wall posters denounced special privileges for Party members, and one showed an abstract nude figure bound like a prisoner by the coils of the Great Wall.

Economic freedom is reappearing as well. In August the government announced that licenses for private businesspeople—canceled during the Cultural Revolution—will once again be issued to hawkers, door-to-door salespersons, and shopkeepers. In Canton alone, 15,000 licenses were issued in August. The rationale for allowing entrepreneurship to resume seems to be twofold: (1) China's economy can't supply the goods and services people want, and (2) unemployment is getting out of hand in the cities. It's expected that hundreds of thousands of licenses will be issued.

Last winter's decision to allow communes and individuals to farm private plots and sell the produce seems to be paying off. This fall there has been a glut of vegetables, fruits, eggs, and even pork in the markets, attributable largely to individual incentive and the much-maligned profit motive.

Range War Escalates

The range war over federal lands in the west has entered a new phase, with the State of Nevada openly challenging the federal government. "It is time to wrest the land from the perfidious absentee landlord who resides along the banks of the Potomac," exclaims Nevada state Sen. Norman Glaser. And in that spirit the Nevada legislature passed a law claiming ownership of 49 million acres of federal land and allocating $250,000 for a lawsuit to challenge the Bureau of Land Management's title to it.

This "sagebrush rebellion" stems from passage in 1976 of the federal Land Policy and Management Act, which directed the Bureau of Land Management to hold federal land "in perpetuity" instead of systematically disposing of it. As explained previously in these pages (see "Trouble on the Range," Dec. 1977), Nevada ranchers, miners, and timber interests were already chafing at the BLM's restrictive use policies, and the 1976 act proved to be the last straw. Nevada Atty. Gen. Richard H. Bryan is seeking advice from constitutional scholars around the country and vows to file the state's suit "within six months."

Nevada's action is picking up support. The Western Association of Attorneys General has endorsed the lawsuit, as have 19 state land registrars and the Alaska legislature. A measure calling for similar action passed the California legislature but was vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown. And in late September the Western Region of the Council of State Governments, meeting in Helena, Montana, passed a resolution asking Congress to force the federal government to sell all its land to state and local governments and the private sector. Another resolution called for civil disobedience by Western legislatures through concerted enactment of laws defying federal statutes and regulations.

The reaction in Congress so far is mixed. Rep. Morris Udall, chairman of the House Interior Committee (which would have to approve any legislation disposing of federal lands), thinks Congress would turn down such a measure. But Sen. Orrin Hatch already has 11 cosponsors on his bill to reverse the 1976 policy and set up a Federal Land Transfer Board to dispose of federal lands.

Private Health Care in Britain

Britain's socialized health care system is ailing. The waiting list for elective surgery grew by 40 percent in the past two years, to 750,000 patients. In several cities, reports Wall Street Journal London correspondent Jonathan Spivak, elderly patients must wait two years for hip replacements; children, three years for tonsillectomies. Last winter, unionized hospital orderlies refused to wheel patients to elective surgery. Moreover, the National Health Service provides no health screening or preventive care whatsoever, not even routine physicals.

Under these conditions it's hardly surprising that private medical care in Britain is suddenly booming. There are now eight private health plans enrolling 2.5 million members; the largest—British United Provident Association—is growing at 10 percent per year. Though accounting for only two to three percent of Britain's annual health care spending, the private plans are the only segment of the industry actively building badly needed hospitals. The need for such facilities is so great that even an American firm has gotten into the act, investing $85 million in building seven private hospitals in England and Wales.

But the most ironic aspect of the situation is the fact that union members are now starting to opt for private medical care too. (It was the labor movement, of course, that pushed through socialized medicine after World War II.) In July, 1,500 Birmingham brewery workers became the first union group to sign up. They were followed in August by the 40,000-member Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunication, and Plumbing Union. That defection caused a great outcry from the hospital workers' unions, but to no avail. Some 10,000 London taxi drivers have also joined up.

When even trade unionists find that private medical care is more responsive to individual needs, and worth paying extra for (on top of taxes to support NHS), advocates of State medicine had better do some hard thinking. Are you listening, Senator K.?

Radio Deregulation on the Way

"For many years detailed FCC regulation of radio was thought essential to guarantee that the voices of a few would not so dominate the air waves as to drown the dissenting opinions and tastes of many others. Today the data…indicate that as the number of radio stations has dramatically increased, listeners have been offered a wider range of choices, largely despite, rather than because of, government regulations."

So saying, the Federal Communications Commission proposed to drop two of its regulations of radio stations: limitations on the amount of commercial time and requirements for certain percentages of news or public-affairs material. The nation's 4,548 AM and 4,105 FM stations would be left free to determine such policies in the marketplace. The proposal would also remove the FCC from "detailed consideration" of public-affairs programming as a factor in license-renewal proceedings and eliminate the requirement that broadcasters keep minute-by-minute program logs. But the FCC would leave in place the Fairness Doctrine and the present equal-time regulations.

Reaction to the proposal was generally positive. The National Association of Broadcasters was pleased with the plan and "optimistic" that it would be approved. CBS, Inc., surprised some observers by saying that the FCC "ought to apply [deregulation] to television too." Announced September 7, the proposal is open to public comment for at least 90 days (through early December), after which there will be another 60 days for industry response. Thereafter, unless the FCC is persuaded otherwise, it will go into effect.

New Satellite Market

While the Carter administration tries to figure out its policy on remote-sensing satellites—that is, whether and to what extent NASA should continue in the earth-resources-sensing business—Comsat General Corporation is well on the way to entering the field on its own.

The demand for such services is being articulated by the Geosat Committee, a not-for-profit organization representing about 100 oil, gas, mining, and engineering companies. What they have in mind is a high-resolution, stereoscopic earth-sensing satellite system—something far more advanced than NASA's present Landsat satellites. "Most of the world has not been adequately mapped, geologically," noted Geosat's William Trollinger. "Without stereo, it is virtually impossible to produce even a rudimentary geologic map, because the third—vertical—dimension is missing."

Comsat is making detailed economic studies of the viability of the satellite and hopes to reach a go/no-go decision by next April. With all the billions of dollars that oil and gas companies are budgeting for exploration, Comsat's William Mayo thinks "it is a distinct possibility that industry may finance the entire project," rather than expecting the taxpayers to share in the cost.

Milestones

Bond Fraud. The US Treasury is being sued by the Gray Panthers. The charge is fraudulent promotions. The subject? Savings Bonds. The group argues, in a petition filed with the FTC, that failure to disclose the impact of inflation makes the ads for Savings Bonds fraudulently misleading.

Quitting SS. Alaska state employees have voted to withdraw from the Social Security system, effective January 1. They will choose from among five alternative retirement plans set up by the state government. "I think this signals to the federal government that there is a concern about taxation, and I wouldn't be surprised if this begins to happen nationwide," said Commissioner of Administration Bill Hudson.

Puncturing Air Bags. For the second year in a row, the House has voted to ban the Transportation Department from spending any money to enforce its regulations mandating air bags in cars. The move is largely symbolic at this time, since the regulation requires air bags in large cars by 1982, mid-size cars by 1983, and compacts by 1984.

Shooting Down the IRS. The Senate has voted 47-to-43 to forbid the IRS from spending any money to enforce its regulations that would remove the tax-exempt status of private schools for failing to meet certain racial quotas.

Freeing Conrail. The government-supervised, nominally private Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail) says it can get off the federal dole—if Congress will only deregulate the railroad industry. Under deregulation Conrail would be able to lop off unprofitable branch lines or increase rates enough to cover its costs. But continuing to operate within the morass of ICC controls will continue Conrail's need for subsidies, according to Chairman Edward G. Jordan.

Plastic Ban Voided. A 1977 Hawaii law that would have made it illegal to sell beverages in plastic containers was ruled "vague and unconstitutional" by a state circuit court. The law had been passed in the name of litter control.

College Defies Feds. A second independent college has joined Hillsdale College in refusing to certify to HEW that it is in compliance with Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. Grove City College, which accepts no federal funds and does not discriminate against women, maintains that it is exempt from the law and has no intention of becoming involved with the federal government. When negotiations with HEW broke down, Grove City took the agency to federal court, seeking to have the law declared unconstitutional, as applied to a non-federally aided college. Hillsdale has already obtained such a ruling from an HEW administrative law judge—but HEW is appealing.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Trends."

Show Comments (0)