The Great 1979 Social Security Heist

Taxes hikes 31%. Benefits slashed 20%. Happy New Year.

You've got to hand it to the US Social Security Administration. What other agent of any government could say of itself that it spends more each year than the Pentagon, that it takes more from America payrolls than the Internal Revenue Service, and that its own employees want no part of the program they administer?

The 41-year-old Social Security system has passed some interesting milestones along the way. The almost embarrassing surpluses of the early 1940s have become the nearly five-billion-dollar deficit of 1978. In 1979, after nearly a decade of spending billions more than was taken in, the Social Security system will "balance the books," so to speak, with a tax increase so enormous that it amounts to taxing every man, woman, and child in the nation $500 a year whether or not they work.

Social Security will balance the books by taking in more money this year while making the benefits much worse. The maximum Social Security tax payable in 1979 will have increased by a whopping 31 percent while items like maximum family death benefits are going down nearly 20 percent. This is a very direct way to balance the books. It is also a stunning national fraud.

The fact is that the 1979 Social Security tax increase is so large that the 95th Congress feared going home to face the November elections without enacting an income-tax reduction totaling $18.7 billion. As Rep. Al Ullman of the House Ways and Means Committee put it, this way "the average guy can just hold his own after what Social Security is going to do."

But we need much more than a "tax break" such that the Social Security system's price tag won't strangle the average budget. We need to know more about what Social Security really is.

Most Americans aren't aware that more payroll tax goes to Social Security than to the IRS. Social Security has never been a major issue in a national election. Could it be that we just don't care?

More likely is that most Americans believe that, whatever the cost, Social Security protection is top-of-the-line, the best that could be gotten anywhere. That, anyway, is what we're told to believe. So while Congress debates whether it's easier to take money out of paychecks as "withholding" or as "FICA," nobody is asking whether the protection we're buying is really any good. It isn't.

Keeping the illusion intact, however, is a full-time job. We either can't or won't see that income protection and retirement benefits can be reduced to insurance needs with well-established and well-regulated price tags. We can get that protection from many sources, including the federal government. But the federal government doesn't like to discuss price, and when it comes to describing protection versus cost, it seems they'd rather we looked the other way.

Thus, when the privately financed Research Institute of America and the California Taxpayers' Lobby sought Social Security information, during 1976 and 1977, for their readers and contributors, both were told of the hypothetical Richard Williams family and how well the family is protected by his Social Security contributions.

The family, according to the administration example, is headed by 35-year-old Richard Williams, a salesman who has always paid the maximum Social Security tax. His wife, Mary, cares for the couple's two children, ages four months and three years, in their home. We are told, cheerfully, that even though Richard Williams has only worked since 1971 and will have contributed (as of mid-1978) only $6,033 to Social Security, he and his family are protected by more than $364,100 worth of promises from the federal government—a tax-free bonus of more than a third of a million dollars made up of potential death, survivors', and retirement insurance benefits.

COMPUTING AN ILLUSION

How can a program be bad when it sounds so good? The answer rests in the financial fudging, manipulation, and out-and-out lies used to compute the Richard Williams "typical example."* Rather than reaping a financial windfall, the Richard Williams family and the millions of other American families just like them suffer a secret loss every year. Here's how it works.

Using the Social Security death and survivors' benefits as an example, the administration describes the "value" of Richard Williams's government life insurance as $241,543. These are the assumptions: If Williams died in 1978, Mary and the two young children would be entitled to receive $1,059.40 per month in a family benefit check until the Williams's older child (three years old) reached 22. With 228 such monthly checks, the total would be $241,543.20. At this point Mary's benefit would stop, but the two children would continue to receive $908.10 per month until the younger child (four months old) reached age 22, assuming he remained a full-time student. This additional 32-month benefit would total $29,059.20. So far the benefits in this example total $270,857.40, including the $255 to cover part of Williams's burial expenses.

But, says the government, this isn't all. Though Mary Williams would stop getting her own survivors' benefit when her younger child reached 18, she could apply for widows' benefits as early as the age of 60 and receive a monthly check for $432.86. Assuming Mrs. Williams survived to age 78, this annuity, says the administration, would be worth $93,497.98.

There you have it, we are told. For a modest tax contribution of less than $6,100, Richard Williams can rest easy with the assurance that his family is protected to the tune of $364,100.38. Further, we are assured, Williams's family protection level will rise each year he lives as long as his wages continue rising with the cost of living.

The trouble is that Williams's "protection" costs more than his government tells him it does and is worth considerably less.

In the first place, his Social Security bill has not been $6,000 during his working life, but $12,000. For some unfathomable reason the Social Security Administration persists in telling taxpayers that the cost of the program is the amount in his paycheck box marked "FICA," even though it is widely understood that the employer is required to match that amount before sending the money off to the government.

In a June 1974 statement published in the New York Times, Commissioner Cardwell described the employer's portion of the Social Security tax as "simply a cost of doing business" and thus not part of the employee's cost of protection. This is, as University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman has labeled it, classic bureaucratic double-think. Cardwell's conclusion simply cannot be supported.

During 1978 the hypothetical Richard Williams (and anyone else earning $17,700 or more in wages) will have had $1,070.85 deducted from his pay for Social Security. This amount, however, will not satisfy the Internal Revenue Service, which acts as a collection agent for the Social Security Administration. The total that the IRS expects from his employer as a result of Williams's labor is $2,141.70. What is to be gained by the sham of telling Williams and others like him that the "cost" of his Social Security protection is $1,070.85 when the government demands $2,141.70 and will not accept one penny less?

The endless economic wrangle over who really bears the cost of the "other" $1,070.85 simply clouds the issue. What is being studied here is the number of dollars the federal government demands in order to make the promises made to Richard Williams. The answer is $2,141.70 in 1978.

COMPOUNDED FRAUD

Still, one might ask, why quibble over $6,000 when Williams's family was promised 60 times that amount should he have died in 1978? The hidden $6,000 is important because it compounds the incredible fraud of identifying Williams's Social Security promise as being "worth" $364,100. It is in fact worth so much less that Williams and others like him are actually overpaying the government more than 100 percent every year!

The real value of Social Security's promise to the Richard Williams family is less than half of what the government says it is. And the real cost of making this promise is less than a third of what the government is demanding in taxes.

To simplify matters we will accumulate the Social Security Administration's overstatements as we go along. When the federal government promises Richard Williams that his family will get $1,059 per month for 228 months, one assumes that administration actuaries are aware that it does not cost $241,543 to make such a promise. Money paid out over a number of months or years, of course, has time to earn interest, so that the sum total of payments is not needed at the beginning. Since the Social Security Administration employs more than 50 full-time actuaries and many others on a part-time or consulting basis, we can be certain they are familiar with the financial truth that it doesn't cost $100 now to offer someone $1 a month for 100 months.

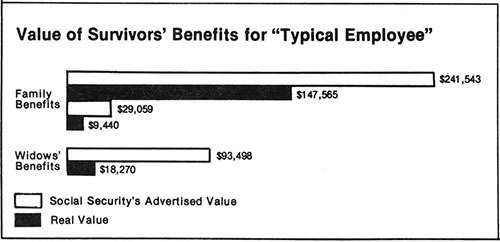

The real question the Richard Williamses of America must ask is how much would have to be deposited in savings to assure one's family of $1,059 per month for 228 months. Even if we assume a minimal passbook rate of 5.5 percent, we find that the cost of that promise is not $241,543 but $147,565. The government has overstated its promise to Richard Williams by 63 percent, or $93,978.

To continue, the government then promises that once the youngest Williams child reaches 22 the family benefit will be reduced to $908.10 a month, to remain at this level for 32 more months. By carefully multiplying $908.10 times 32, the administration concludes for us that this additional promise is worth $29,059.20. As before, however, all is not as it seems.

Again the question to be answered is, How much money would Richard Williams need today to be able to duplicate the government's guarantee to his family? For a total of $29,059.20 due in 32 monthly installments of $908.10, a fund of $26,107 held at 5.5 percent interest would cover the payments.

So far we know the "additional" $29,000 is worth no more than $26,000, but the federal actuaries know a lot more than that. Remember that the first part of Williams's benefits ($1,059 per month) would be payable immediately on his death, but the "additions" wouldn't be due to start until 228 months later, when the first benefit runs out.

We should then change our question. How much money, we should ask, does Mr. Williams need now to be able to assure payment of $908 per month beginning more than 19 years from now? The answer is that he would need to set aside only $9,440 to cover the payments—not $29,059, as the administration example implied.

This time the government overstatement of the value of the promise made to Richard Williams is a whopping 200 percent, or $19,619, bringing the total discovered "error" thus far to $113,597. And the worst is yet to come.

The Social Security Administration values the widows' annuity due Mary Williams at $93,497.76 because she is entitled to receive $432.86 each month at age 60 and is expected to live another 18 years afterward. We have seen enough so far to realize that the price has been set much too high.

Richard Williams in 1978 could bequeath his 35-year-old wife a $432.86-per-month pension when she reached 60 by insuring himself for $18,270 today. Surely one of those administration actuaries knew that $93,497.76 overstates the government's pension offer to Mr. Williams by an incredible 411 percent.

DELIBERATE DECEPTION

Why isn't Richard Williams told the truth—that his federal insurance death benefit, burial fee, and annuity package has the wrong price tag attached? Instead of $364,100, the real potential value of the offer to Williams is $175,275. It is impossible that an entire bureau of federal actuaries does not realize that the "Williams example," so proudly displayed, is in fact a 107 percent error that overstates the real value of the government protection by more than $188,825.

Nor is this all of the "Williams example."** In the full reports designed "to show you in exact dollar terms just how much your Social Security is worth," we are told that families like Mr. Williams's are due potential benefits of "over $700,000" on taxes already paid. This figure is so absurdly false that it de-serves no more mention than as an example of the depth of the administration's deceit.

The $700,000 amount is arrived at by adding to the already discussed $364,100 additional "potential benefits" in disability protection and retirement annuities for Richard Williams himself. The last two "benefits" are calculated in the same manner as the death benefits we've already looked at.

No American worker could discover a more lucid illustration of the intelligence estimate his government has made of him than by studying this example. In order to reach the "potential benefit" of $700,000, workers like Richard Williams would have to discover a way to become 100 percent disabled at 35, die at 35, and still work to age 65 before dying again at the mathematically average age of 78. To add up three different programs that could never be paid to the same family during the same lifetime must establish some record for lunacy.

These examples are not, of course, administration mistakes. They have been carefully designed to produce the precise attitude that exists today. The American Social Security system is based upon the belief, by people like Richard Williams, that a promise of $364,100 (in death and annuity benefits alone) is a fair return for the $2,141.70 in Social Security taxes the government demanded of Williams and his employer in 1978. It is sustained by the further belief that a 31 percent increase paid in 1979 will buy a 31 percent rise in real protection and keep the system solvent. Neither is true. Protection will go down.

The truth is that American working families will have much less protection per tax dollar in 1979 than they had in 1978. The ratio of taxes to benefits will become slightly worse in 1979 and every year thereafter. What will grow are the taxes paid by wage earners and the promises needed to make the taxes seem just.

On July 1, 1972, then-Social Security Commissioner Robert M. Ball assured Americans that the 20 percent rise in Social Security taxes, set for 1973, would count fully "toward the benefits that will be payable to them and their families in the future." In fact, the rise in Social Security taxes during 1973 and 1974 came to more than 46 percent—the largest two-year hike in history—and made the protection picture even bleaker for working Americans than before. The benefit increases only seemed to be going to them.

In 1979 the deception is much more direct. Instead of the $2,141.70 in employee/employer taxes that was due in 1978, the maximum tax for 1979 is jumping 31 percent, to $2,807.54. But what if Richard Williams lived another year? What would happen to all the increased tax payments to Social Security? Incredibly, the Williams family would get less!

If Richard Williams were to die in 1979 instead of 1978, the following would take place: The Social Security Administration would be in line to collect another $2,807.54 in addition to the $12,000 already paid into the Williams account during his career. His two children would be one year older, so the family would receive benefit checks for one less year. Last, but not least, the family benefit would drop from $1,059.40 per month to $852.20—a mind-boggling reduction of 20 percent.

The reason for all this is not only quite simple but gives an excellent insight into the way the administration sees the future of Social Security.

In 1970, the present round of giant Social Security tax increases began. The maximum payroll tax jumped 164 percent in the next seven years. But we were told not to worry—that benefits were going up, too.

The most reassuring news we heard was that benefits would automatically rise with the cost of living ("Private insurance certainly can't do that for you," clucked former HEW Secretary Wilbur Cohen). So we endured the largest payroll tax increases in history, secure in the knowledge that our protection was going up right along with the prices of bread and milk.

Then, very quietly, the bubble burst. The economists and accountants at Social Security began to see that the promises made in 1970 and 1971 were very expensive, that "coupling" the benefits with average wages and cost-of-living increases wouldn't "save the system," as they said, but would bankrupt it.

Thus a plan was devised to "decouple" the benefits structure—to in fact diminish the Social Security benefit obligation by changing the way benefits are calculated. This became law in 1977 to take effect on January 1, 1979. People like Richard Williams are protected by considerably less in 1979; in fact, all new benefits have been scaled down by at least five percent.

Yet the tax is not going down. In 1977, the year the new "decoupling" law was passed, lowering future obligations of the system, the maximum Social Security tax went up nearly 11 percent. The 31 percent Social Security increase effective this year is the biggest annual payroll tax increase of any kind in the nation's history—coming in the very year benefits are going down!

Small wonder, then, that the deficits of the Social Security system will evaporate in 1979. By 1980, the administration proudly notes, the system will actually have a surplus of $2 billion.

We simply should have listened more closely. When we were told, in 1970, that "the system was secure forever in the future," what was meant was that, if we would agree from time to time to pay much more tax for fewer benefits, they would continue to send out the checks. Wilbur Cohen was right on when he told us that "private insurance certainly can't do that for you."

Having seen just how badly Social Security has overvalued the worth of its benefits to us, we can look at the real cost of offering the package.

We know the federal estimate of Richard Williams's protection value was inflated by at least 100 percent. We find, also, that the system sees nothing fraudulent about raising the tax while lowering even the inflated benefit. But what about the true risk the government takes in offering any of these benefits?

THE REAL PRICE TAG

In the government's example, 35-year-old Richard Williams died in 1978 leaving behind a 35-year-old wife and two children aged four months and three years who were both to go to college. His Social Security tax bill that year was $2,141.70, which came entirely from the payroll of the company employing Williams although only half the amount appeared on his paycheck stubs.

The government added up all the benefits it would pay the Williams family in the next 43 years and declared that Williams's "protection" is worth $364,100. The actual level of protection, of course, is $175,275. But the level of protection is not the same as the cost of protection. The real "cost" is much lower still, and the Social Security Administration knows this very well. The fact that most Americans don't know the real price tag for Social Security is what keeps the system afloat.

The problem is that the Social Security Administration expects us to believe whatever it says. If we are told, as we were in scores of newspaper defenses of the system in 1974 and 1975, that we "should think of Social Security as group insurance," we are expected to buy this. Yet when describing our benefits, the administration uses such childishly illogical examples that any comparison with insurance is impossible.

This is what the federal government would rather we didn't understand. If someone like Richard Williams wants to know the real cost of the protection bought with his Social Security taxes, he would certainly not add up the amounts on the next 43 years of benefit checks he's promised. That would be assuming that money has no value and so would earn no interest at all. When offering its own Treasury bonds to private investors, the government seems to understand very well that money has value. The Federal Reserve regularly offers to pay citizens 8 percent interest or more for accepting its Treasury notes.

Thus Richard Williams and others would certainly agree that assigning the nominal value of 5.5 percent to his federal promise and reducing it to $175,275 is quite reasonable. But he shouldn't stop there. He should be asking himself about the actual chance that he will die at 35. After all, the true cost of offering a promise is based upon the likelihood of having to make good. Insurance, as the administration is fond of calling its program, is the science of assigning value to certain risks. And any actuary will confirm that the chances that Richard Williams will die at age 35 are less than 3 in 1,000.

UNGENEROUS PROTECTION

Now we can take a better look at the system its commissioner, James B. Cardwell, lauded in early 1975 as "the greatest and most generous source of protection for the American worker." If we assume a group of 1,000 workers who at age 35 paid in 1978 the maximum Social Security tax of $2,141.70 (there are more than 1.8 million in this category), we arrive at total "contributions" to the government of more than $2.1 million. Since only three of these taxpayers were likely to collect the death, survivors', and annuity benefits promised in 1978, the risk taken by the government for the $1.5 million is $525,825, or three times the $175,275 cost we've established. That's one-fourth of the tax collected, leaving more than $1.5 million.

Obviously the Social Security system is not the most efficient way for people like Richard Williams to solve what is essentially a problem of risk protection. For Mr. Williams to guarantee his family total future payments of $364,100 should he die at 35, what he really needs is an estate of slightly more than $175,000 available in the year he dies. This does not cost $2,141.70 per year to create. Any insurance company, using a standard group-rate table, could sell Richard Williams or any other working 35-year-old all the financial protection needed to duplicate the death, survivors', and annuity benefits in our current example for $630 in annual premiums.

Keep in mind that the $2,140 paid on behalf of Richard Williams in 1978 was used to create all of the benefits his family could receive on his behalf after his death that year. This assumes all of the burial benefit, all of family benefit checks for the following 19 years, all of the student benefits for the next 3 years, as well as all 18 years of the widows' annuity to Mary Williams. Yet for $630 Richard Williams could have bought the $175,275 in life insurance necessary to pay those bills.

But the real cost of Social Security protection is hidden even deeper. Being insured privately for the same amount of money the government promises would mean much more to the Williams family.

Private insurance would pay off in cash—not in monthly payments. In his will, Richard Williams could appoint an executor to consult with Mary on how best to use the money. Social Security regulations demand that full family benefits could not be paid if Mary Williams decided to return to work. Nor would the family get the full amount if the children didn't complete college—or if Mary were to remarry. The exceptions go on and on.

Social Security is simply not good protection. It is overpriced, deceptive, and uncertain. The system that promised to be "the best financial security for young families" overcharged Richard Williams $1,000 in the year he died—1978. And this year, in just one year, the overcharge has been doubled.

Warren Shore is the former consumer affairs editor of Chicago Today and the author of Social Security: The Fraud in Your Future (Macmillan, 1975).

*It is not the purpose here to impugn the motives of either the Research Institute of America or the California Taxpayers' Lobby, as both groups appear to have acted on what was believed to be reliable government information.

**In some publications, the same or similarly computed figures appear with the family name changed to Jones, Brown, etc.

Fixing Up Social Security—Bandaids or Major Surgery?

The Social Security Administration would have people believe that, by paying into the system via FICA taxes, they are saving for their future. In fact, however, the funds collected are used up almost immediately to pay out current benefits. It's known as the pay-as-you-go system.

But with birth rates falling and life spans lengthening, fewer and fewer workers each year must finance benefits for more and more retirees and survivors. The system can only be kept pay-as-you-go by decreasing the benefits or increasing the taxes. This is what the 1979 changes in Social Security are all about, although the simultaneous boost in taxes and reduction of benefits has not been trumpeted about.

The problem with this patching up of the program is that it leaves untouched a serious side-effect—reduced private saving and thus capital formation. Since many people regard Social Security as a form of saving, the system discourages saving and encourages current consumption. Which is just what the government had in mind when the system was set up during the Great Depression.

The idea then was that people were saving too much and not pumping enough dollars into the economy by way of current consumption. Social Security would get people to save less, and the benefits paid out would be spent on goods and services, thus promoting full employment.

Much later, many of the economic assumptions underlying this diagnosis and treatment came to be questioned. And in 1974, Martin Feldstein, an economist at Harvard, published a study which estimated that Social Security indeed reduces total private saving—by about 40 percent. If Social Security were in fact run like the trust fund it is often characterized as, this mightn't be so bad for the economy. Workers' in-payments would be invested—like private savings, insurance funds, etc.—in the economy's productive enterprises, allowing them to flourish and the workers' funds to grow. But with a pay-as-you-go system, the diminished private saving means that firms have available to them less investment funds, so that interest rates are higher (about 28 percent), wages are lower (about 15 percent), and the capital stock is lower (about 60 percent) than in the absence of Social Security. All this means an annual reduction of some 20 percent in economic activity (GNP).

A growing awareness that the system is not only precariously underfunded but a huge drag on the economy has led people to start casting about for solutions. One—the most cosmetic—is for the Social Security system to build up a trust fund by collecting even more tax monies and disbursing even lower payments. Another is simply to do away with the system, allowing people to substitute private pension and insurance plans for Social Security or to purchase government "retirement" or "social insurance" bonds. These special bonds would, upon retirement, provide an annuity.

In a proposal put forth in 1968 by economist James Buchanan, the FICA payroll tax would be replaced by employees' purchase of such bonds, whose annuity benefits would be based on the higher of the long-term Treasury bill rate or the GNP's growth rate. In 1975, Charles Hobbs and Stephen Powlesland, under the auspices of the Institute for Liberty and Community, proposed that the payroll tax be abolished and individuals be allowed to choose between investing a minimum amount of annual income either in private pension programs or in retirement bonds. At retirement (or death) these bonds would provide an annuity to the retiree (or surviving family) based on their accumulated value and on standard actuarial criteria. As a transition measure, present participants in Social Security would be given retirement bonds with an annuity value equal to currently promised benefits. These bonds would be financed by the sale of other retirement bonds and by increasing income and other taxes.

A different system was suggested in 1975 by Warren Shore, under the name "New Generation Compact." Individuals entering the job market would have a choice between the present system and a private package of life, retirement, and disability insurance. For every individual electing the private plan, the insurer would assume payment of benefits to one worker retiring one year later. Premiums would be based on gross income, but the mix of coverage could be adjusted to individual needs. Participants in the present system could waive their benefits under it and opt for private coverage. Gradually, as payments to new retirees were picked up by private insurers along with newly insured workers, the Social Security system's present obligations would be phased out.

None of these proposals addresses another problem with the present system—its compulsory nature. Under the alternative schemes, individuals would still be forced to make some kind of provision for their retirement, with the amount and form generally specified and regulated by the federal government. A study yet to be completed by the Cato Institute in San Francisco, however, promises an analysis of proposed alternatives and a proposal of its own for phasing out Social Security and putting old-age and survivors' care back into people's own hands, with individuals taking or leaving one of the many coverage packages offered by private insurers.

—Marty Zupan

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Great 1979 Social Security Heist."

Show Comments (0)