Houston Defies the Planners…and Thrives

Development gone berserk? Boiler-factories next door? No. Houston's refusal to zone has brought economic vitality.

A city of nearly two million people that doesn't have zoning, has never had zoning? Traditional urban-planning beliefs would lead us to expect an uncivilized, dirty, chaotic mess. Houston, however, is quite the contrary. The nation's fifth-largest city is attracting new residents at the rate of 1,000 per week. It's become the corporate and financial capital of the South, and many people, particularly those from the corporate headquarters relocating there, say that Houston is the most livable and exciting city in the United States.

Why isn't Houston one huge disaster area? What factors determine land use in an unzoned city?

PRIVATE PLANNING

The first and primary factor is the private marketplace. Contrary to popular impression, the marketplace is not chaotic. In fact, the evidence is that it produces a very orderly, structured, and predictable land use pattern. Different land uses in Houston, as in other cities, have different inherent locational requirements. The director of Houston City Planning, Roscoe Jones, once pointed out that he had a hard time understanding why so many non-Houstonians supported zoning, raising the bogey that they didn't want a gas station moving in next door. Because, as he pointed out, gas stations have very specific locational requirements; they must be on major thoroughfares, preferably at an intersection of two or more major thoroughfares. They'll pay 10 or 15 times the value of other properties just to get that location. Even if you were to give them property in the middle of a residential area, they wouldn't locate there.

Similar types of locational requirements are found with commercial retail stores, again preferring to be on a major thoroughfare. Industrial facilities have their own locational requirements—generally, larger tracts of land at lower or medium cost, frequently with rail access. And single-family and multifamily dwellings thrive in specific locations—in many cases based on the value of the property, but generally avoiding the highway frontage that commercial users tend to seek out.

So overall, the marketplace does present orderly and predictable land use patterns. Perhaps, as Denver developer Warren Bailey has pointed out, the land use appearance of Houston is not so different from that of many other cities. Part of the reason may be that zoning in other cities has been so ineffectual that it has not been able to alter very much at all the natural locational requirements. Regardless, the fact is that lack of zoning does not permit chaos or somehow make Houston a less desirable place to live.

A second factor that determines land use in Houston is deed restrictions. These are private stipulations put into the deeds, commonly referred to as restrictive covenants. Houston probably has the most extensive use of these covenants in the nation—there are between 7,000 and 8,000 subdivisions in Houston covered by them. Basically, a deed restriction is a kind of insurance policy on land use. It's a private contract, generally between the original developer and the people who purchase the property, that states the specific details of what that person can do with his land. They generally apply for 25 or 30 years but are renewable at the end of that period. Some of the restrictions are renewed, and some aren't. It depends on how conditions have changed over 25 or 30 years and whether or not the residents want to continue to preserve the conditions that were originally protected. Professor Bernard Siegan, in his book Land Use without Zoning, concluded the following about restrictive covenants: "Communities can function reasonably well and the values of homes and other real estate can be maintained and enhanced without the need to give homeowners much more protection than they are afforded by restrictive covenants."

A third type of land use influence is the city's subdivision regulations, and the street patterns and so forth that are determined by them. Houston has those, just as other cities do, and there's nothing particularly unique about them. Likewise, a fourth factor is Houston's relatively standard building codes (relating to new construction) and housing codes (relating to existing construction). The fifth type of land use determinant is the plan for major thoroughfares and freeways, which the Planning Department administers. Certainly, that has a major impact on determining the location of future growth. But again, that traditional bulwark of planning—zoning—does not exist in Houston. In fact, it's been proposed and voted down several times, the latest being in 1962.

REDUCING COSTS

So much for the fears of chaos. But nonzoning also has benefits. First, one of the major advantages is lower costs. A good way to reduce housing costs is to increase the supply of housing available. By its very nature, zoning tends to do just the opposite. It restricts the new land available for single-family or multifamily housing to land specifically zoned for that use. Thus, it limits the supply of housing.

Costs also tend to increase because zoning requirements (especially in the suburbs but also in the central city) generally try to force residential development at a low density. Large lot requirements are common in the suburbs, and when a developer comes in, local planners in 9 cases out of 10 try to get him to increase his lot sizes. Of course, that's going to increase the cost of that housing to the consumer. Also, while trying to keep the density of development down, zoners are helping to create the urban sprawl they so often lament.

Look at the photo on page 17 of a recently constructed apartment project in Palatine, Illinois (a suburb of Chicago). You can see the very wide open expanses, which are perhaps attractive to some, but you can also see the valuable land involved with all that open space. Needless to say, the extra costs of that vacant land end up in the rents of this sort of development. By contrast, the adjacent photo shows an apartment project in Houston also completed within the last 10 years. You can see it's much higher density—25-30 units per acre here, compared with a density in the Palatine project of perhaps 9 or 10 units per acre. As Siegan pointed out in his book, the rents in Houston (though going up like those in all other cities) are 10-20 percent lower than in a comparable city like Dallas. Siegan attributes the difference in large part to the fact that there's no zoning in Houston to limit the amount of land for apartments nor the density of development.

A second benefit of nonzoning is that it allows for greater adaptability to changing conditions. The apartment boom of the mid-1960's, which resulted from the postwar baby boom, hit most cities very hard. There were widespread apartment shortages. But not in Houston where there was an apartment surplus for many years because there was no zoning to limit the amount of land that could be developed for apartments, leading to a very competitive situation.

The adaptability of nonzoning is also illustrated when we look at the energy crunch of the last several years. As the cost of travel goes up, outlying areas become more attractive for office space. And again, where there is no zoning that would tend to keep out office or commercial development, it can take place much more readily. Also, while outlying areas become more preferred for commercial uses, inlying areas simultaneously become somewhat more attractive for higher-density residential uses.

The first tendency is illustrated by Greenway Plaza—a massive office and hotel complex being developed in what was one of Houston's residential areas. Greenway represents, in effect, suburban redevelopment, bringing office facilities closer to where people live. Ask yourself how many cities with zoning have completely reorganized their zoning ordinances to reflect the increased cost of gasoline or the changing market conditions of real estate. Very few. It's extremely difficult to adapt with zoning, because it's such a massive task to modify it every time there's a change in economic conditions or energy supplies. Houston, in that sense, is very fortunate when it can adapt, as it is doing now, to these changing conditions.

COMPETITION'S BEAUTY

A third benefit of nonzoning—and this might seem surprising—relates to esthetics. Take a look at the adjacent photo. Is this project zoned, or not? With zoning, the developer's competition is limited to the land that is zoned for similar uses. In the case of apartments, the demand generally exceeds the supply, and the developer is able to spend the least he can, just meeting government requirements. He has minimal need to compete, meeting market requirements, because the market is limited—or his competition is limited. Zoning can't force developers, in spite of low-density requirements, to make anything attractive; all zoning plans can do is to confer order. (Some people refer to it as the order of a cemetery). The photo of course, does show a zoned community. The apartment buildings are in Mount Prospect, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago.

Marc Putnam, a Minneapolis landscape architect, makes the aesthetics case as follows: "As to the visual appearance of zoned communities, their montonous uniformity is largely attributable to uniform restrictions. Apartments show results of forced compliance with zoning regulations specifying uniform setbacks, uniform lot sizes, uniform side yard distances, height limitations, backyard requirements, etc., etc." And David Mandel recently put it this way in Architectural Forum: "Repealing zoning is no guarantee of architectural excellence. One thing is certain: ugly buildings will continue to be built. But architectural excellence is encouraged by freedom, not by conformity to stale committee judgement."

Nonzoning in Houston encourages the provision of "extras" because of the competition to attract buyers and renters. Note the suburban Houston apartments shown on page 20. It has a much higher density than you'd find allowed in most zoning ordinances. But it shows creative use of the space: the structures are arranged in an interesting fashion; landscaping is used extensively—and the rent is relatively cheap. Overall, it's much to the benefit of the renter for the developer to have the freedom to respond to the renters' needs and desires.

A fourth benefit of nonzoning lies in private renewal and self-rejuvenation of the city. Cities evolve and change; they're not constant. But zoning by its nature, tends to, or at least tries to, arrest that evolution. With self-rejuvenation, individual homes that happen to have been on a major street are converted into commercial uses as market conditions and real estate prices suggest that these homes be adapted to a different use. In contrast, neighborhoods in northern cities that might have survived are being totally obliterated by "urban renewal" and their humanity trucked away with the rubble. That's partly because zoning condemns these areas to total devastation before modification or rebuilding can occur.

It's not at all clear what zoning is protecting in a decaying neighborhood. It would be nice if some zoned cities were to experiment with little islands or pockets of unzoned land in the most rundown neighborhoods. Just remove zoning from those areas and see what kind of development they attract. The planners and city officials would no doubt be pleasantly surprised to find that the freedom of developers to build in any fashion they want would attract a certain amount of development and could start turning an entire neighborhood around.

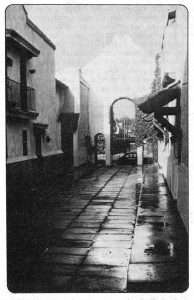

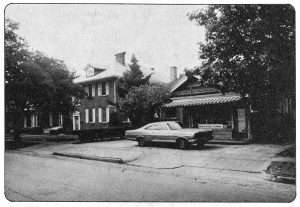

Below are some examples of private self-rejuvenation, on Westheimer Road in the Montrose area, at the fringe of downtown Houston. Here you see some older homes that have been converted for different uses—some into restaurants, some previously single-family houses into multifamily, etc. Another photo in the same general area (p.21) shows a real mix of land uses. You can see a single-family home on the corner, probably one of the oldest structures in that neighborhood, with a row of townhouses next to it that have certainly helped improve the appearance of the neighborhood; a high-rise apartment project on the right; and an office building on the left—all these uses seemingly getting along quite well together.

Another type of redevelopment is the larger-scale project, such as Greenway Plaza. In 1969, Century Development purchased three residential subdivisions in this area. On the 1962 proposed zoning map (the one that was defeated) the area in which Greenway is being built would have been restricted mostly to single-family and apartment buildings, with only a few commercial structures. One of the things that made Greenway Plaza work is the fact that the Southwest Freeway was built adjacent to this land, and the homes built prior to that time suddenly became more valuable for commercial use. Century purchased the 237 homes at market price plus 10 percent, gave the owners rent-free occupancy for five more years, and allowed each owner to remove the structure itself or salvage anything from it. What they told people was that if there were any holdouts, they would not go ahead with the project. So they didn't give people any option of trying to hold out and make any money on it, because if they did the project would not have gone through. They eventually got 100 percent acceptance—though there was one holdout who got several hundred thousand for his property.

Another example of large-scale private redevelopment is Houston Center, being developed by Texas Eastern Transmission. This project (p.16) in the downtown area, is even larger than Greenway Plaza. Texas Eastern assembled 32 square blocks through a dozen front companies over a period of years. Without zoning, there was a completely open situation for the developer—assuming he could get the property. This is the largest and most costly private urban development project ever undertaken in the United States. Cooperation from the city has been good, even to permitted development over the city streets. The company is building a four-level parking area, with a pedestrian mall above all that to separate the pedestrian and vehicle traffic. They even have plans for their own private transit system. The first building has been completed, and the second one has just been topped out.

ZONING—WHO'S FOR IT?

A fifth advantage of nonzoning is the opportunity it presents for small businessmen. On p. 22 we can see a businessman who has a flower shop in the front room of his home. You can see that this type of situation (and there are numerous examples all over Houston) does not especially present any sort of land use conflicts. You may find a beauty shop that's mixed in with the residential areas, a home that has been converted into a retail shop, an insurance office that has been added onto a home close to downtown in an older neighborhood.

In this regard, it's interesting to look at the voting pattern in the 1962 zoning referendum. The strongest support for zoning came from the suburban areas, the newer-developed areas. It's rather ironic that this is the case because these areas have the strongest deed restrictions and probably had the least to fear from any sort of "incompatible" land use intruding into their neighborhoods. The strongest support for nonzoning came from the minority and low-income neighborhoods. These people realized that if they had zoning it might limit some of their small-business opportunities; it might keep them from taking advantage of increasing property values and converting their land later on to commercial use. Zoning was soundly defeated by the lower-income and minority neighborhoods.

The question now becomes: Has the nonzoning lesson been learned? Have zoning or public controls increased the amenities or attractiveness of cities? Most planners have probably never even asked the questions. Look at those cities that have had zoning the longest. New York, Chicago, Detroit, etc. We don't have a very good record there for zoning; it doesn't make these cities more attractive. But the sad fact is that the lesson has not been learned. Observe this passage from the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation's widely read and widely quoted book, The Use of Land: "If our cities and our metropolitan areas are to survive, we need to change the policy of allowing property owners to think they can do what they want with their land merely because it's theirs. Owners must come to recognize that whatever rights they have in land they happen to own are rights accorded them by society, not rights which they grudgingly permit society to abridge." In this entire publication, there's not one mention of Houston, the fifth-largest city in the United States and by far the largest city without zoning. You'd think Houston's experience would deserve at least a footnote!

At least we're beginning to hear some dissent. David Mandel, for example, writes in the Architectural Forum: "Zoning plans face the problems of the future with the full confidence that they can prevent 1938 or 1959 from ever coming back. The maps are, and have to be, drawn in the light of old technology, old resources, old problems, and old ideas. They are inherently inflexible, unable to adjust to new technology, new resources, new ideas, and new needs."

Overall, then, there are five good reasons to go with nonzoning rather than zoning. Nonzoning generally results in lower costs, especially for housing. It permits cities to adapt to change more rapidly—in particular, one can refer to the examples of the apartment boom and the energy crisis and the way Houston has been able to adapt to both. Then there is the matter of improved aesthetics—the fact that regulations and controls cannot make something attractive, but in fact quite the opposite, that the variety and innovation resulting from unrestricted private entrepreneurship are what produce improved aesthetics. Nonzoning also encourages private renewal and redevelopment, or at least eliminates one of the major obstacles to such redevelopment. Finally, nonzoning presents much more opportunity for the small businessman to get started in a small operation and also provides the opportunity for people to be closer to their stores, shops, hairdressers, and other services, because those uses can be mixed in with the residential land uses. In a zoned city, the general idea is to separate commercial from residential uses; zoning actually makes it inconvenient for people to get those services and goods.

Is Houston behind the rest of the country in land use controls, as most planners outside of Houston might suggest? On the contrary, it's way ahead of most of the country. While planners may be the last to admit their mistakes, they may be learning. A lot of them are starting to see the results of some of their repressive controls. They're noticing all the monotonous subdivisions and developments and are starting to suggest that zoning be modified to allow planned unit development, mixed land uses, and some other innovative things like transferable development rights. All these are steps toward more freedom—toward the Houston situation. Those planners who say that Houston needs to get in step with the rest of the country, need some sound advice: Get in step with Houston.

Formerly a city planner for Houston, Mr. Bjornseth now does private consulting in land use. He cofounded AREA—the Association for Rational Environmental Alternatives—and this article is adapted from a talk given at an AREA conference in Houston, May 1977.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Houston Defies the Planners…and Thrives."

Show Comments (0)