Here Comes Voluntary Education

During the ferment of the sixties and early seventies a new movement of school reform surfaced to challenge the public schools. Essentially, the reformers have made two criticisms—public schools are immoral and they are unnecessary. Their immorality stems from their reliance on force and coercion to supply them with students and operating funds. Compulsory school laws have been used to force children into the schools in order to be exposed to the values current among the political majority. At the same time, parents and others are compelled to support the public schools whether those schools support their aims or not. Increasingly, the arguments used to legitimize this force have come under fire.

Proponents of public education have argued that it is necessary because democracy requires an informed citizenry or because some parents would fail to provide for their children an adequate education. Recent studies have demonstrated, however, that the schools do not produce an informed citizenry. A group of researchers at the University of Texas found that roughly one third of American adults have the skills to function competently in everyday life; another third can get along marginally; while a final third simply can't make it. In studies of political and economic awareness, Americans are consistently found to be ignorant of the basic processes of both their political and economic systems. Nor do the schools do well with those children who might be neglected by their parents. Both low-income and minority children do consistently worse than their upper-income counterparts. The public schools fail with most children, and fail even worse with the children who presumably need their services most.

While many reformers attempted reform, others chose to work for a voluntary alternative to the tax-supported, compulsory public schools. In a burst of enthusiasm, it seemed to many that the future was now. Education would be freed. It would become responsive to the wants and needs of the students, the parents, and the teachers. But with bills to be paid and floors to be swept, the enthusiasm faded and the hopes dimmed. Many look upon the public schools as an unbeatable monolith, yet it seems they are giving up too soon. A number of trends are putting increasing pressure on the tax-supported system of schooling. Over the next generation the virtually unchallenged preeminence of public education will be eroded. The initial process will be slow, but as momentum builds, opportunities to expand the voluntary sector will increase dramatically.

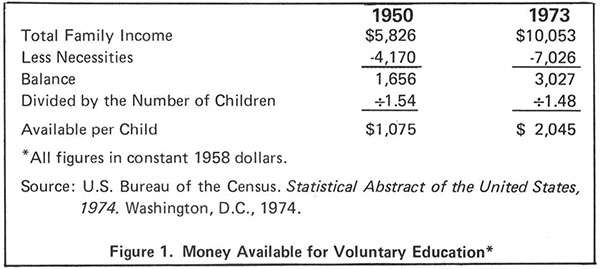

First let's look at trends in the market that are likely to enable voluntary education to broaden its share of the market. The most significant is the money that a family can spend on voluntary education. That money is a composite of two other factors—the number of children per family and the family's real income. By dividing the money available for voluntary education by the number of children in the family, we arrive at the amount available per child. This amount has been rising substantially in recent years as, per family, the number of children declines and the amount of real income increases. Figure 1 illustrates this relationship. Families at increasingly lower income levels have the option of voluntary education that was previously available only to the rich or at great sacrifice. Of course this trend only means that the money is available. It does not guarantee that it will be spent on voluntary education.

Nevertheless, changes in the makeup of the population are working to make it more likely that parents will choose voluntary education. Parents themselves are attaining higher levels of education, reflecting increasing demand in the economy for so-called knowledge workers. Parents are becoming more sophisticated educational consumers, and education is becoming an increasingly necessary service. This trend is reinforced by the ever-higher proportion of work-force participation by married women with children. If both parents work, this increases potential educational dollars per family and boosts the need for the educational system to handle many of the tasks undertaken by parents when one or both worked in the vicinity of the home. Combine this with the rising dissatisfaction with the public schools, and the result is a substantial potential market for voluntary education. But that market will materialize only if voluntary education can satisfy the needs and wants of consumers of education.

Voluntary education is likely to be assisted in that task by a technological revolution in education. Over the past 40 years, and especially in the last 10 or 20, knowledge about human beings and the way they learn and develop has exploded. Most of this new knowledge is yet to be applied. When it is, and when it is combined with new machine technologies and managerial techniques, the effect will be dramatic. Costs will probably be brought down by half or more at the same time as the quality of education is substantially improved. If this occurs it will bring voluntary education within financial reach of virtually anyone interested in it.

What direction is this revolution likely to take? By building expertise into instructional materials, the roles of teachers and students will change. Education employs essentially the same methods as did the earliest recorded schools of the ancient Sumerians. The teacher still stands in front of the class and lectures. The most effective way to transmit information, however, is through books, audio tapes, films, television, and other instructional materials. The teacher is best exploited in the uniquely human ability to solve problems. Today's teacher is so busy lecturing that there is no time to work out the learning problems of individual students. The result is that many students go through their entire school career learning little, producing the farcical scene of high school graduates who can neither read nor write.

The role of the student, too, will be revolutionized. It is clear that in a properly conducted and supplied school the student can not only take on more responsibility for his own learning but can also help his fellow students who know less than he does about the particular subject. And the helping student is often helped the most—in his knowledge as well as in self-discipline and self-concept.

Thus there are a number of trends within our society that are making it possible for a greatly increased number of people to opt for voluntary education. This is so even if they must continue also to support, through taxes, the public system.

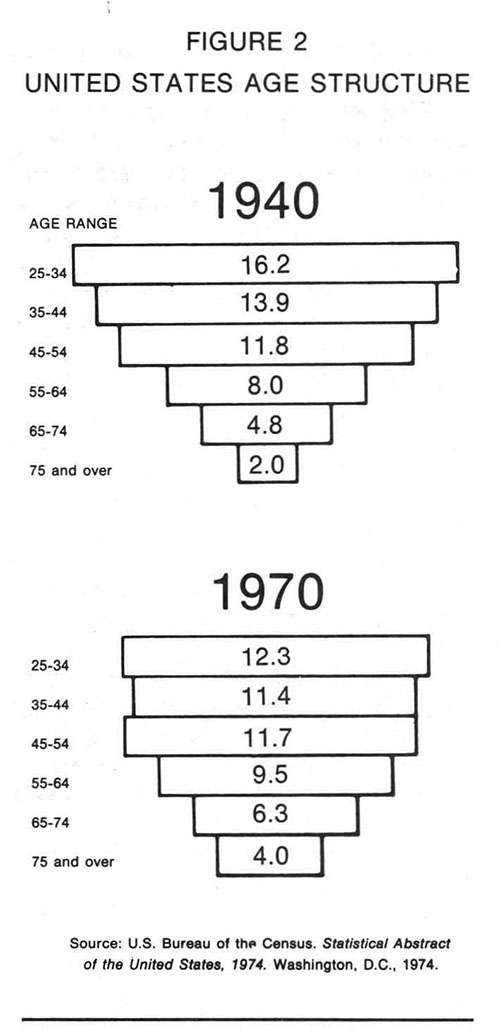

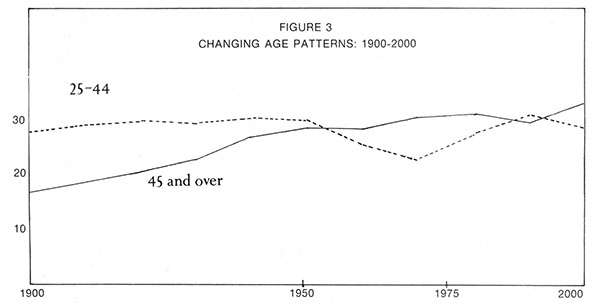

Yet there are also trends working in the political sphere against tax-supported education. The most important one has, in effect, already occurred. It is the shift in the age structure of our society. Increased life spans combined with lower birth rates are moving the United States from a pyramid-shaped age structure to one that looks more like a rectangle. This is illustrated in figure 2. To understand the implications of this trend, consider the political process. Unlike that of the market, it tends to be responsive to the largest group at the expense of smaller and politically less potent ones. In the political context, this means the groups of voters. Up to this point the tax-supported school system has not been a terribly inequitable system. At any given time most of the taxpayers were also parents and thus received some benefits from the system. But as figure 3 illustrates, the shifting age structure increases the proportion of the voting population not receiving benefits. This trend will be reinforced considerably with increases in the number of parents not sending their children to public schools. This shift takes time to operate, but over the next 40 years a situation will evolve in which most of the voters in any given election are not gaining from supporting the tax system. This poses the real possibility of its being cut back radically.

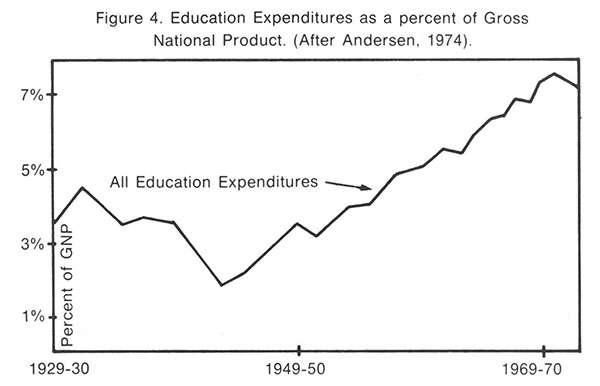

Another factor that is likely to have impact on the political situation is the increasing resistance of the electorate to higher taxes. Taxes are very close to the upper level that is acceptable. Thus the schools cannot expect much in the way of increased taxes. The public schools' problems in this area are compounded by the fact that their share of the tax revenues have risen quite dramatically in the last 20 years (see figure 4). While part of this rise is due to a greater number of pupils and the growth of real wealth in the country as a whole, public schools have also increased their total share of the tax monies. More money has allowed them to defuse some of the problems that are facing them, but that solution is not likely to be available in the future.

Thus there are a number of trends within the political sphere that are likely to weaken the public system's access to tax money. In the short run, the schools will probably be unable to obtain the increases in money to which they have been accustomed over the last two decades. During the next 20 to 40 years the changing age structure is likely to substantially erode their base of political support. This latter trend will be gradual for a while, but once most voters are not receiving benefits and a substantial number are bearing a double burden, it will speed up considerably.

The public schools have more immediate problems, as well, mainly with the issue of who is to run the schools. This controversy has been explicit in New York City, where minority-group parents have fought with the school bureaucracy as well as the teacher's union. It is also at the heart of the fight over school textbooks in Kanawha County, West Virginia. Parents with strong religious convictions rebel against the texts supported by the more secularly oriented parents who constitute the majority. The most important expression of this battle is that between the parents and the Federal courts over busing to achieve racial balance. The issue of school prayer is another problem that is a low-level but continuing source of conflict. The separation of church and State required by the U.S. Constitution prohibits any official (school-sanctioned or -initiated) prayers in the government schools. At the same time, a large segment of the population favors such prayers. It is unlikely that either side will change its position. These conflicts have had an effect on public opinion. A recent Gallup poll shows that popular support for public schools is eroding, most strongly among the young and the better educated.

There is probably a tendency among people within the voluntary school movement to underestimate the public schools' ability to react. There are very large numbers of good people within them working hard to produce quality education. They are bright and concerned. In addition, although public support is eroding, it is vast. Most people were educated in public schools and continue to support them. Finally, they do have the advantage of being able to offer their product to the consumer at no apparent cost since they are financed from tax revenues. All these factors militate against the inspiring trends.

On the other hand, people operating in the public schools face real difficulties. Precisely because the schools are a creature of the government they are intimately involved in the political processes that surround it. This means that they have to be responsive to the dominant political group. While this is in some sense as it should be, it does make the tax-supported schools unresponsive to the diverse groups that are in the minority-racially, politically, economically, or whatever. As more groups achieve the political and economic means to enjoy alternatives, the schools' problems are complicated further.

Political involvement also makes for considerable difficulty in implementing innovations. Typically, the community does not support novelty, and the major innovations that do occur are the result of short-term school-board majorities. These coalitions usually come unstuck, resulting in the cancellation of the innovation.

An additional handicap faced by the public schools is their bureaucratic structure, inevitable as a government agency. Bureaucracies are infamous for their resistance to change. With the schools, this resistance in large measure flows from the incentive structure. For teachers, monetary incentives encourage longevity in the job and a higher level of formal education. There are no rewards for better methods of teaching or better student performance. The only way to advance is to get out of teaching and into either administration or higher education. Many educators recognize this problem, but the situation itself compounds the difficulties of remedying it. Efforts toward its solution have been largely ineffectual to date.

The problem of incentives is of course compounded by a lack of understanding of the change process, by tenure, and by the relationship between the schools and the teacher organizations. Together these factors work to insure that change will be a slow and agonizing process. As if this were not enough, the declining rate of growth in the number of children of school age means that there will be little hiring of new teachers. Even that route for introducing change will be largely closed.

Thus the tax-supported schools are faced with the problem of attempting to meet a changing situation with essentially the same people in the same structure and with little in the way of a mechanism for internal change.

On the other hand, there are considerable incentives to continue the development of innovative processes. Part of the great sums devoted to education over the last few years have gone to create a considerable educational research establishment—educational laboratories, university centers, and individual researchers. Their reason for existence lies in educational change. While they will doubtless be cut back somewhat with the lower emphasis on education, their mere existence as a pressure group will insure them of some support. Also, there is an important commitment to research and development that will prevent their being wiped out. The new processes and products developed by these centers are likely to point to defects in the current system. Thus while the schools are unlikely to be able to change easily, the educational research people, also largely supported by tax money, will be constantly pressing for change. The resulting conflict will probably further erode not only the public's confidence in the schools but their own confidence in themselves.

Overall, there is likely to be a continuing commitment to change accompanied by little actual innovation. The pace of change will slacken considerably from the not very high levels of the sixties and early seventies. The economic problems of the mid-seventies are likely to bring about a marked slowdown from which there will be only a gradual recovery.

We can conclude that over the next two generations the tax-supported schools are likely to be weakened on two fronts. Their basic political support base will be slowly undermined as the age structure evolves, and they will be faced by an educational situation changing rapidly in important ways. Adaptation will be hampered by the resistance to change built into being a bureaucratic component of a political system. At the same time, the public schools will retain massive strength simply by virtue of their access to tax funds, which allows them to provide a product at no apparent cost to the consumer.

The voluntary schools will hasten the political problems faced by the tax-supported schools to the extent that they are able to develop viable private, voluntary alternatives. Growing numbers of parents who must bear the double burden of taxation and support of a voluntary alternative will more than proportionately increase the pressure for relief from the tax burden. To the extent that alternatives are available to many groups across the social and income spectrums, the political impetus for change will be strengthened.

Creating a viable private voluntary alternative, however, is not easy in the face of the remaining strengths of the public system. Simply attempting to do exactly what the public system is doing is futile. People interested in voluntary education have to develop an opportunity-seeking orientation. They have to address the needs that are not being met. They have to find the cracks, the interstices, that the public system ignores. They have to revel in the diversity that the public system abhors. From their successes in the areas that the public system is unresponsive to, they can draw the strength to move into ever more direct competition with the tax-supported schools. And they can do it successfully.

The public schools arose in the 1840's partly to replace a decaying apprenticeship system and partly to satisfy the native American majority's desire to inculcate their values in the growing number of immigrants. That context is gone, and those purposes are long forgotten and dead. Americans are more tolerant and even proud of the variety of cultures and points of view that coexist within American society. A system of voluntary schools can arise in this new context to provide diversity within education. Voluntary schools can offer a variety of styles of discipline and teaching methods to satisfy parents whose interests lie in a traditional, basic-skills orientation as well as parents who are more concerned with the social-emotional growth of their children. Different approaches are possible for value-laden topics such as sex and religion, where conflicting viewpoints simply cannot be accommodated by one approach. Beyond diversity, voluntary education can offer better education. When students and parents can choose between schools, each school must pay attention to each client's aims and desires. This is a powerful mechanism for making schools accountable. As schools are held accountable for their performance, their incentives for being effective are increased. As they strive for more effectiveness, educational change becomes not a task but an opportunity.

Whether or not the public schools can coast on, protected by their government status, depends on the voluntary schools' response to this opportunity. An increasingly centralized, bureaucratic structure has robbed the public schools of their ability to act. The opportunity and the challenge are in our hands. The decisions are ours, not theirs. The work and thought are ours to take on. The future is the prize.

John E. Bailey, III is a graduate student in educational psychology at Nova University in Fort Lauderdale, FL. He is interested in educational change through market mechanisms.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Here Comes Voluntary Education."

Hide Comments (0)

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mute this user?

Ban this user?

Un-ban this user?

Nuke this user?

Un-nuke this user?

Flag this comment?

Un-flag this comment?