Trading Gold Futures

Among conservative investors the commodity futures markets are held in just about the same esteem as the gambling dens of Lost Wages, Nevada. Although this attitude toward futures trading is understandable, it is also unwarranted. Commodity trading serves an important and necessary function in our economy. And, subject to certain caveats, it can offer the prudent and sophisticated investor valuable diversification with manageable risk.

In primitive economies only cash (spot) markets exist. No single individual or family owns enough of any single commodity to be greatly affected by price changes during the time it holds goods. But in our economy, those who produce, process, and merchandise commodities often have huge quantities on hand. A grain elevator operator, for example, may have millions of bushels of grain in his inventory. If the price slips only 10 or 20 cents per bushel it may wipe out his profit from months of work. The futures market was created to shift this risk to those more willing to assume it.

There are two basic groups of traders in commodity futures: producers, who produce, process, and market commodities, and speculators. Producers use the futures market for hedging. They simply take an opposite position in the futures market from the one they hold in the physical market. What they gain on one position they lose on the other, allowing them to concentrate on making a profit from their production—which is, after all, their primary goal. Speculators are drawn to the market by the prospect of trading profits. They hope to buy low and sell high.

Whether the speculator succeeds or fails in making a profit, his presence in the market is absolutely essential. It is he who assumes the risks involved in handling huge quantities of commodities in a dynamic economy of fluctuating prices. His venture capital helps provide the liquidity the market needs to smoothly and efficiently produce and deliver the goods upon which our standard of living depends.

ENTERING THE MARKET

Futures are ideal for the gold investor with speculative funds who wants maximum leverage for greatest return and who can afford to accept the risk. Leverage cuts both ways; when the market goes against you, your losses are multiplied, just as your gains are when you're winning.

Anyone who can meet the financial requirements of a commodity trading firm (all of the nationwide stockbrokerage houses trade commodities) may trade in the futures market. The initial margin (down payment) required depends on the trading firm; but it may be as high as 25 percent. Once the contract is open, however, the customer (you) may request that everything over the minimum margin requirement be returned to you. Of course, if the market subsequently goes against you, the value of your contract will fall below the minimum and you will get a "margin call," a request for additional margin. Should you fail or be unable to provide the additional funds, your contract will be sold, to protect both you and your broker, and you will be billed for any deficiency.

Since there are only two sides to a transaction—buyer and seller—there are only two possible positions available in the commodity market: long and short. These terms actually refer to the sequence of events. A "long" buys first, then sells; he hopes the price will rise before he has to sell. A "short" sells first, then buys later to "cover"; he hopes the price will fall before he has to buy.

Strangely enough, selling short is not well understood by investors. Actually it's a common practice in business and industry, as well as among individuals. When a farmer sells in May a crop he just planted and won't harvest until September, he's selling goods he doesn't have yet. That's selling short. When a company takes advance orders for goods to be delivered in 90 days and subsequently produces or buys those goods for delivery as agreed, it is selling short. Any business that takes orders from salesmen's samples, such as school ring manufacturers and textile companies, routinely sells short on goods it does not yet have in stock.

A trader who takes both a long and a short position is said to have a "straddle" (both contracts the same commodity and month) or a "spread" (different commodities or months). These are used to speculate on changes between different contracts and delivery dates, to convert short-term gains or losses to long-term and to move gains forward into the next tax year to minimize or eliminate taxes.

When a grain elevator operator has 50,000 bushels of wheat on hand (long) and wishes to hedge his position, he sells 50,000 bushels in the futures market. Since the spot price and the futures price tend to move in unison (although often not exactly), whatever he makes on one position he will lose on the other, leaving him with just his normal profit.

The straddle and spread speculator zeros in on changes in price relationships between various contracts and between futures and spot commodities. His activities help maintain an orderly price structure in the market and between the various exchanges from coast to coast and even continent to continent.

TAX STRADDLES

If you have done some trading this year and in the process have taken short-term gains that will be taxed as ordinary income, you should consider using a tax straddle to move your gains forward into the next tax year or to convert them into long-term capital gains that can be taxed at 25 percent or less.

Keep in mind that, once paid, taxes can never really be fully recovered. If you go ahead and pay taxes on your gains this year and next year you suffer a loss, your only hope is to make a future gain to offset it or to write it off at a maximum $1,000 per year.

But if you push your gain forward, paying no taxes this year, you have some insurance against such a loss next year. You won't wind up paying taxes on a gain that didn't hold up. You'll start the new year with a gain, so you can feel free to take bigger changes, knowing that much of what you are risking is money that you would have lost to the government and that you won't mind spending. Even just converting a short-term gain to a long-term gain is well worth the effort. If you're in the 50 percent bracket, the tax savings on $10,000 amounts to $2,500.

The technique is really very simple. The commodity market is where the action takes place. Usually there's no advantage to taking both the short and long position, since what you gain on one side you lose on the other. And since you must pay commissions on both, the result will be a small loss.

For example, say you buy one March silver and sell short one May silver. Since the contract contains 10,000 ounces of fine silver, every cent up will result in a $100 gain on your long position and a $100 loss on your short position. Net result: neither gain nor loss, just $70 in round trip commissions.

Now suppose that silver goes up (or down) 10 cents between now and December 31. If you sell the contract in which you have a $1,000 loss before December 31, and the one in which you have $1,000 gain after January 1, you will take a $1,000 gain in the next year.

It's that simple. There are only two possible problem areas in this technique, but both can easily be avoided. You must protect yourself from any change in price between the time you sell one contract and the time you sell the other (since you don't want to chance wiping out your gain and suffering a real loss), and you must pick a suitable commodity.

Here's how you do it. Pick a volatile commodity that is sure to move the distance you want (silver is very good), and take your position two or three months before the end of the year so you'll have plenty of time for it to reach the price you want. It's better to count on a smaller move and buy more contracts than to fail to get the action you need. In silver, 25 cents ($2,500 per contract) is about all you should count on. If you want to write off $10,000, you'll need at least four longs and four shorts; five each would be even safer.

Let's suppose you need to move $10,000 in short-term gains forward into the next tax year. Buy five March silvers and sell short five May silvers well before the end of the year, September would be fine. When silver moves up, or down, 20 cents per ounce ($2,000 per contract), sell the contracts that show a loss. Let's say silver moves down; in that case sell the longs for a loss of $10,000 and buy five July silvers to replace them.

Now you still have a straddle but it shows a $10,000 gain. Your shorts are worth $10,000 more than you paid for them and your longs are at breakeven, since you just bought them. If silver goes back up 20 cents your longs will be worth $10,000 more and your shorts $10,000 less, still a $10,000 gain. You're covered against losing your gain no matter what happens to the price.

After January 1, sell all your contracts and take your profit. If you want to convert the gain to long-term capital gains you will have to pick contract months all after June, July, September, and December, for example.

TRADING THE MARKET

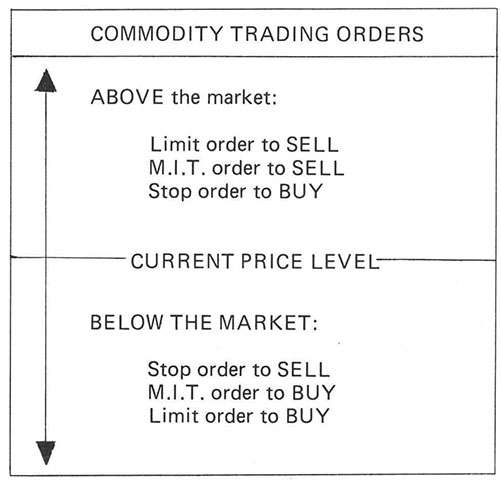

There are only three basic types of orders the trader may give to his broker for execution: market orders, limit orders, and stop orders. Certain additional instructions may be added to each, giving the trader a great deal of flexibility. A market order is an order to buy or sell immediately, at the best possible price. In addition the trader may instruct his broker to use his own judgment and agrees that he will not hold his broker accountable if the execution is less favorable than it might have been if done otherwise. The trader may also instruct his broker to take his time, again agreeing to abide by the result.

A limit order is an instruction not to buy or sell above or below a certain price. It entails the possibility that the order will not be executed at all. Unless otherwise specified, limit orders are standing orders that remain in effect until filled, or until the contract expires. The trader can, however, specify "fill or kill," meaning that if the order cannot be executed immediately it is to be cancelled. He may also specify a "scale" limit to buy or sell a large position in a series of specified steps at different prices.

A stop order is an instruction to buy or sell immediately after a specified price is ticked. When the target price is reached the stop becomes a market order for immediate execution. Of course it may be at, above or below the target price, depending on market action at the time. The trader may place a limit on the price he will accept (a stop limit order) at a specified distance above or below the trigger price. He may place inactive orders (market if touched) above or below the market, which will become market orders once a specified price is ticked. Finally, the trader may make stops in one contract depend upon price action in another contract (contingent) when he believes a change of trend in one commodity or contract month will precede a change of trend in another.

There should be no confusion between limit orders and stop orders. "Buy 7.50 limit" means buy when the market is at or below 7.50, but not higher. "Buy 7.50 stop" means buy at the most favorable price immediately when 7.50 is reached.

TWO BASIC APPROACHES

Speculative traders make their buy and sell decisions based upon two different types of market analysis: fundamental and technical. Very few traders use just one exclusively, although most lean heavily in one direction or the other. Fundamental analysis involves careful and detailed consideration of all available supply and demand statistics, such as production, consumption, transportation, and weather, that may affect the price of a given commodity. Traders who use this method usually zero in on a small number of related commodities about which they feel they have expert knowledge.

The trader who uses technical analysis is known as a "chartist." A pure chartist ignores all fundamental factors. Instead he charts the data from a variety of technical indicators, such as price changes, market volume, and open and short interest figures, to isolate what he believes are reliable trends. He bases his market decisions upon these technical factors, buying and selling when the charts dictate.

The fact is that most traders (including this one) use both fundamental data and chart data to help them "psych out" the market. For example, my own approach to gold is basically fundamental, involving a great deal of historical and economic data. Charts of gold price action over the past few years, however, are also very interesting and informative. Although I lean quite heavily toward the fundamentalist approach, I use chart techniques to back up and validate my theories. For me, the results of this approach have been very satisfying. But then, many chartists feel equally satisfied with their results. In the final analysis, it's up to you. Whatever you feel comfortable with, whatever works for you, is what you should use.

SHOULD YOU PLAY?

There are six U.S. commodity exchanges actively dealing in gold futures: Comex (The Commodity Exchange, Inc.) in New York, The New York Merchantile, The Chicago Merchantile (International Monetary Market or I.M.M.), The Midwest Commodity Exchange, and The Pacific Coast Commodity Exchange. Altogether a large variety of contract sizes and months are offered. Which should you choose?

What you want above all is liquidity. In practice this means a contract with a relatively large open interest. It's much safer to be one of 3,000 contract holders than one of 30. When you want out, you certainly don't want to wait around several days hoping for an execution on your order. The bigger and more active the market, the better.

The prudent investor keeps a close eye on the odds. He only puts his hard-earned money down when the odds are heavily in his favor. He also avoids putting all his money in a single investment, preferring instead to spread his risk. The result of this conservative approach is many good gains with a few small losses (no one wins all the time).

At this point in history the odds heavily favor the gold investor. In noninflationary times the investor has a wide variety of options. But in today's economic climate all the traditional investments have failed. Today there is only gold. I believe gold futures offer the prudent investor valuable diversification with manageable risk.

The first question to ask is: Where do futures fit into your portfolio? It's really up to you to decide. You can tailor the amount of leverage to your own individual needs. At $150 per ounce, a 100-ounce contract is worth $15,000. If you put that amount down when you take your position you cannot get a margin call or be forced to liquidate. By rolling your contract over when it comes due every 18 months, you can maintain your position indefinitely at a total cost of perhaps 8 percent per year. This is certainly less desirable than physical possession, which costs you nothing, but it's still very conservative, and still flexible.

At the other extreme is a minimum margin deposit for maximum leverage of about ten to one. You have so little equity that a relatively small price move against you will result in a margin call. If you are unable or unwilling to put up more cash you will be forced to sell out at a loss. On the other hand, If the price moves in your favor you'll make a real killing with this much leverage working for you. But that's what speculative funds are for, making a killing. You can take a position anywhere between these two extremes.

RECOMMENDATIONS

If you want maximum safety in your investments, don't buy any kind of paper; take physical possession of your gold. Avoid gold shares, margins, and futures.

If you want some leverage at minimum risk, futures can be perfect, especially if you have personal expertise, or access to it, to help you in your timing. You should put down 35 percent to 50 percent. The leverage here is identical to margins offered by U.S. coin firms, but at much lower risk and cost.

If you want to speculate at high leverage, you should limit your investment to no more than 5 percent of your investable assets. Gold futures are a perfect vehicle for this purpose, but you should never disregard the risk involved in this type of game. The key to success in a high-stakes game like this is lots of knowledge and effective use of stops and limit orders. You'll have to become familiar with at least a few charting techniques, such as moving averages and point and figure. If you attempt to play the futures market on hunches you'll lose your shirt. I guarantee it!

René Baxter was educated at the University of Colorado, Arizona State University, and the University of California at San Diego. He operates a consulting firm, René Baxter Investment Services, publishes The Freedom Fighter, Arizona Liberty, and a weekly precious metal coin newsletter, and helped found the magazine Freedom Today. This article is taken from chapter 17 of Financial Survival in the Seventies, copyright 1975 by René Baxter. The book was published by RB Press, a book service run by Baxter and offering books and pamphlets on economics, investment, and tax revolt.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Trading Gold Futures."

Hide Comments (0)

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mute this user?

Ban this user?

Un-ban this user?

Nuke this user?

Un-nuke this user?

Flag this comment?

Un-flag this comment?