Survival Weaponry

In some quarters, the term "survival" has taken on a rather meaningless chic. Those who are still scurrying about seeking political and economic solutions to the disaster which is nearing use it to punctuate their afterdinner conversations so that their listeners will know that they are serious advocates of individual action, not mere political theorists. Others, who order their lives by a synod of newsletters, may have added deadbolt locks to their apartment doors, acquired Coleman lanterns, and filled their coat closets with storable food and common date coins.

If these remarks seem unnecessarily blunt, consider the fact that, barring a deus ex machina resolution of the script, we have reached the leading edge of the imminent and devastating collapse of our civilization. The total destruction of our economy through the creation of fiat money is in its final stages, and the tangible consequences of that fact will undoubtedly provoke a near-term crisis of catastrophic proportions, unless preempted by a more impatient disaster. World famine and domestic terrorism are darkhorse doomsday triggers, and we are only a Kissinger-concession away from losing our national sovereignty through nuclear blackmail as a result of attempting to preserve the offal of détente with a liberal application of SALT (I & II).

If you remain committed—at this precarious point—to bailing out our sinking ship of state without bothering to don a life preserver, or if, in making your survival preparations, you continue to regard the ripening crisis as an event combining the best features of a weekend campout and a unique investment opportunity, the coming months may present some rude surprises. In a social environment such as ours; when nothing more than a transient power blackout brings forth an army of muggers, rapists, looters, and worse, or when a "student demonstration" requires mobilizing the National Guard to restore order, the consequences of a total economic collapse such as we now face will be neither inconsequential nor short-lived.

With no communications, no food in the supermarkets, no power, no reliable water supply, no police and fire protection, the cities will die quickly as one by one they fall to riots and become engulfed in fire storms, and the surrounding countryside will bear the onslaught of starving, panic-ridden hoards escaping the devastation of the cities. Soon—and perhaps for the rest of your life—your two most pressing concerns may be staying alive during a period of unrestrained mass violence and providing food for yourself and those you care for. In this milieu, something more than casual survival preparations seems to be called for.

Certainly, a means of escaping from the large cities or any area of dense population—preferably to an established, well-stocked retreat—is necessary insurance now. Anyone who believes that it will be possible to weather the storm in a major metropolitan area simply does not grasp the enormity of the problem.

A good selection of storable food is also prudent, but beware of what you buy and don't assume that a so-called one year's supply will necessarily keep an active adult in good health for 12 months under conditions of stress. Find out how many calories and nutrients are actually supplied and how much of the protein is assimilable.

Some alternative to government paper, such as gold and silver coins, will be necessary for preserving one's wealth, but don't fall into the trap of believing that money in any form will be very useful until a long time after the collapse. Trade goods such as ammunition, fishhooks, and needles may be far more valuable, initially.

THE NEED FOR WEAPONS

Important as these considerations are—and no one of them should be neglected—they are inadequate. No retreat on the North American Continent can be considered completely safe from roving bands of looters or terrorists. Storable food will have to be supplanted sooner or later if for no other reason than the fact that human beings cannot maintain health for more than 12 months without essential fats, and such lipids cannot be successfully stored for more than six months without becoming rancid. Coins, bullion, and trade goods are likelier to attract trouble than to buy you out of it during the crisis period.

Further, when the bell rings, you may have to fight simply to reach your retreat, and almost certainly you will have to defend it at some time during the crunch. Even if you choose to grow your food instead of hunting for it, you will have to contend with predator and pest control at your retreat and, possibly, feral animals—some of which may be rabid. Clearly, then, weapons to protect you from violence and to provide a continuing source of food are among the most critical requirements of the survival equation. Without them, the rest of your preparations are simply unrealistic.

I realize that some readers may be opposed to firearms on ideological or pathological grounds and no amount of argument, certainly not this brief prologue, is going to persuade the pervicacious, despite the fact that hoplophobia may prove terminal under survival conditions. My personal experience as a survival consultant leads me to believe, however, that there is a much larger group made up of people who are unarmed or inadequately armed either because they have not focused on the central importance of weapons in survival planning or else because they have been misled by superficial advice. Selecting the best combination of weapons for use under long-term survival conditions is not as simple as some would have you believe, but neither is it impenetrably arcane, and it is certainly important enough to warrant the necessary investigation. Cliché answers lose their charm when your life is at stake.

CHOOSING YOUR WEAPONS

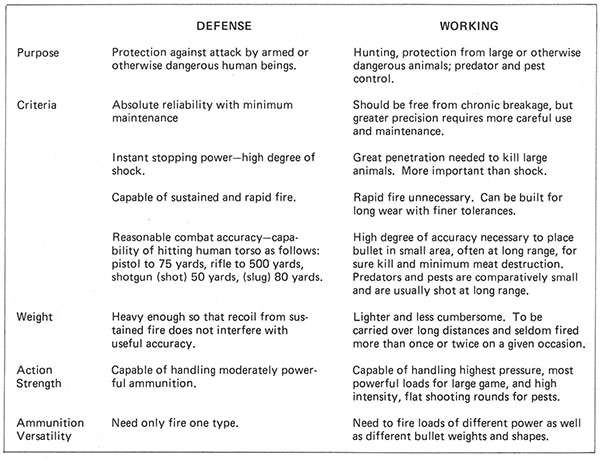

A gun is simply a tool and, like most other tools, the more specialized it is, the more efficiently it will do its job. Just as you would not expect to drive nails with a saw or to cut boards with a hammer, neither should you anticipate using one firearm, or even one type, to perform all of the critical functions which the survival situation may demand. Each individual battery will differ, of course, in terms of the specific uses anticipated by its owner but, generally, the guns you should choose will fall into two broad categories: defense and working. The criteria for selecting each type differ considerably, and perhaps the accompanying comparison, adapted from my book Survival Guns, will prove useful in defining those differences.

What emerges from an examination of the comparison in the table is that it is necessary to own two distinctly different batteries of guns if one is to be reasonably prepared for living self-sufficiently. Now I have no doubt that a few extremely skillful people could—and may—survive with inadequate tools. There are also people who walk away from high speed blowouts in automobiles, incredibly high leaps from burning buildings, train wrecks and plane crashes, but it hardly seems prudent to rely on being a statistical exception, particularly when all it takes to be properly prepared is the expenditure of some outrageously inflated dollars.

You can kill a deer with a .22—under perfect conditions. You can also carve a canoe from a tree with a penknife; but neither is easy nor particularly practical. If you learn nothing else from this discussion, remember this: don't plan to improvise. While you still can, get enough guns and get the best. Regardless of how carefully you plan your retreat, there will almost certainly be unanticipated circumstances that will force you to improvise and, perhaps, make great demands upon both your emotional and physical strength, but they can be confined to noncritical areas. If you lose your matches, you can make a fire by at least a dozen other means, given time; but if you are attacked by a band of looters or set upon by feral dogs and you are inadequately armed, it could cost you your life.

With these distinctions in mind, let's examine the advantages and limitations imposed by the three major classifications of arms—rifles, shotguns, and handguns.

RIFLES

The need for a good centerfire rifle is probably the most universally recognized firearms requirement among those who live outside the cities, and for most of us the rifle will be virtually an indispensable tool in survival planning. It will put more meat on the table per ounce of ammunition expended than any other gun, and no other portable weapon can provide the reliable long-range defense potential that the rifle offers.

City-oriented people occasionally question the need for a defensive rifle, since shotguns are somewhat easier to hit with and pistols are more convenient to carry. When I counter with the facts that shotguns are strictly short-range weapons and that hitting rapidly and consistently at more than 50 yards with a pistol, while possible, cannot be relied upon, those who have never been under fire often remark (1.) that an attack launched from several hundred yards is not dangerous or (2.) that there is plenty of time to escape and hide. I can only reply that even if the first contention were true, which it isn't, determined attackers seldom remain at long range if they do not encounter effective return fire; and running away—assuming that you were willing to do so—might not be an option allowed by your opponents. Looters tend not to be bound by the Geneva Convention.

Although it could be done, stalking a deer in the woods with an assault rifle sporting a 20-round magazine, dangling a bipod and crowned with a flash-hider is not particularly convenient. On the other hand, a scope-sighted, bolt action sporter is not ideal for standing off an attack on your retreat by a dozen or so armed men. Furthermore, the heavy magnum which you might need if you settle in bear country would leave very little of a cottontail for the stew pot. Consequently, unless yours are very unusual circumstances, you may need several different kinds of rifles, and I suggest that, if you must economize or improvise, you do it in some less essential area of your planning. Don't skimp either in quality or quantity when you choose your rifle battery.

In particular, do not make the mistake of selecting a hunting rifle for defensive use. If you absolutely cannot afford both, you will stand a better chance of staying alive if you use your battle rifle for hunting than the other way around. Bolt, pump, and lever actions are all too slow to be considered for fighting weapons which may be called upon for rapid, sustained fire, and none of the semiautomatic sporters is designed for the volume of fire and abuse that a battle rifle must withstand. Further, it is difficult, and in most cases impossible, to modify some of the better examples of these rifles—such as the Browning BAR—to accept large-capacity magazines. It is also an error to choose an underpowered rifle such as the GI .30 Carbine, which, though fairly well designed as a defensive weapon, fires a cartridge that is greatly limited with respect to range and totally inadequate for any purpose except hunting very small game.

CHOOSING A RIFLE

Probably the best single choice for the purpose would be one of the more modern .30 caliber assault rifles chambered for the 7.62 NATO (.308) cartridge, although a .30/?06 Garand will do, preferably modified. Such a rifle in the hands of a reasonably skilled marksman is capable of certain hits on man-sized targets to at least 400 yards, and it is powerful enough to penetrate body armor and chance barriers such as automobile bodies and the like. The Beretta M-59 is my current personal choice, although the SIG and the FAL are both acceptable. I am awaiting the arrival of an M 1A from the Springfield Armory for testing, and if it proves satisfactory, it may offer the best combination of price, availability, and quality to be had in the United States.

As a backup, or for use by teenagers and small statured adults, one of the better 5.56mm (.223) battle rifles such as the Ruger Mini-14 or the Armalite AR-180 should work well. The cartridge is readily obtainable, since it is a current U.S. military round, and it offers excellent accuracy and reasonable stopping power to perhaps 250 yards. Recoil is practically nonexistent, and, consequently, the guns made to fire it can be quite compact and very light.

Hunting rifles for use in open country, where shots to 350 yards might be taken, should be extremely accurate and capable of firing a fairly powerful cartridge, since the vital area of deer-sized animals is quite small. Any survival gun should be durable and easy to repair, and its ammunition should be popular and widely available. These criteria suggest a bolt action sporting rifle, preferably mounting a good 2x7 or 3x9 power variable scope and chambered for a cartridge in the .270, .308, .30/'06 class. Carl Gustav (Husqvarna), Sako, and the recently discontinued Browning are the very best quality, although the Winchester Model 70, the Ruger M 77, and perhaps the Remington 700 will all serve. An additional scoped bolt action in .223, if you have chosen that caliber for a defense rifle, or in one of the other good varmint calibers, is also highly desirable for predator and pest control as well as for sniping.

For further information on working rifles, I highly recommend Jack O'Connor's excellent and very complete book, The Hunting Rifle. W.H.B. Smith's definitive reference, Small Arms of the World, provides brief descriptions and complete specifications for both defense and working rifles and my book, Survival Guns, contains a lengthy chapter discussing each type from the standpoint of long-term survival use.

SHOTGUNS

The primary value of shotguns for survival is defense; however, there are a number of special circumstances in which they can be particularly valuable in gathering food, despite the fact that their range is extremely limited and their ammunition is both heavy and bulky. The hands-down choice for both purposes, and especially for defense, is the 12-gauge. If you expect to make extraordinarily extensive use of a shotgun for hunting, you may wish to own a quality double, either a side-by-side or an over-and-under, since they will last almost indefinitely with little maintenance or repair. On the other hand, the two-shot limitation makes them impractical for defense, and I would strongly recommend an auto or a pump for that purpose, as well as for occasional hunting.

Probably the most efficient short-range fighting weapon I have ever seen is the High Standard Model 10B auto riot gun. Its gas operation greatly lessens the recoil effect, and it is designed to be used conveniently with one hand if that should become necessary because of an injury. A specially designed Kel-Lite police flashlight that mounts on an integral bracket is available, and it serves as an aiming device in the dark. The Browning 2000 and Winchester Super X gas-operated autos are also satisfactory when equipped with 18-to-22-inch "deer" or riot barrels. My choice of the pumps is the Remington 870, preferably with the 20-inch "deer" barrel, rifle sights, and the police eight-shot magazine extension.

For defense under a wide variety of circumstances, I greatly prefer the 12-gauge #4 buckshot loading to anything else. It is double-distilled dynamite to 25 yards or so, and acceptable to about 35. Across a room, any 12-gauge shot load will do. For longer ranges and for hunting deer-sized animals in dense cover, nothing else quite matches the Brenneke slugs, and for birds or small game, #6 high-base loads are the best all-round compromise.

If for some reason you cannot select a 12-gauge, ammunition availability and relative effectiveness suggest the 20-gauge as a second choice, but in standard loadings you will have to settle for considerably less effectiveness. At a distance of six feet against a human adversary, the difference might not matter; under any other circumstances, it will.

There are literally hundreds of books in print on various aspects of shotgunning, but most of them are concerned with the finer points of bird-shooting and other recreational sports. I am aware of nothing current except my book Survival Guns that discusses the defensive use of shotguns in any detail, but both O'Connor's The Complete Book of the Shotgun and Francis Sell's The American Shotgunner are excellent from the hunter's standpoint.

HANDGUNS

Were it not for the inconvenience of carrying shotguns and rifles, there would be no real need for handguns in the survival battery. If you were anticipating an attack upon your retreat, or if you were setting out on a hunting trip, desperate for food, the handgun probably would not be your weapon of choice, because it is harder to shoot accurately than a rifle, it hasn't the spreading pattern of a shotgun, and, at its best, it is less powerful than either rival can be. But sooner or later you will be tempted to leave your retreat without your rifle or shotgun—perhaps to bring in a load of firewood, work in the garden, forage for wild edibles, feed your livestock, or drag up a freshly killed buck for butchering. At such times your pistol becomes the most important weapon in your battery. It is a tool that should be chosen carefully, learned well, and carried always, for when it is needed, it is apt to be needed emphatically.

I have read more utter nonsense about selecting and using handguns for defense than about any other weapon. The cliché recommendation is usually a small .38 Special revolver, and the reasons usually given for that curious choice are that anything more powerful is too hard to handle, that nothing more is needed, and that revolvers are more reliable and easier to learn to shoot than autopistols. Such advice is—to say the least—dangerously inept, and to act on it may very well cost you your life. Almost any conscientious researcher in the field will have in his files hundreds of shooting-incident analyses that demonstrate beyond any reasonable doubt that the .38 Special at its best—which means hot loaded and used in a long-barreled pistol—is successful in stopping a determined opponent with a solid hit on the torso less than 50 percent of the time. This figure correlates with the scale of relative stopping power developed by General Julian Hatcher, based on extensive tests conducted by the Army in the early 1900's in an attempt to discover why the .38 had failed so miserably during the Philippine insurrection. These findings indicate rather conclusively that bullet diameter or caliber has more effect than any other element on the ability of a projectile driven at pistol velocities to stop a human opponent.

The .45 ACP cartridge which was adopted by the U.S. military as a result of these tests—and still in use today—has proved both in theory and in fact to be capable of one-shot stopping power about 95 percent of the time. The percentages of effectiveness do not increase significantly above that figure regardless of the handgun employed, but controllability problems do, and for that reason I recommend the .45 as the optimum cartridge for defensive use.

With the modern, two-hand hold, or "Weaver Stance," which anyone using a pistol for serious purposes should adopt, almost any person over the age of 12 who weighs at least 90 pounds should experience no control problems whatsoever in firing the .45, even in rapid-fire strings. In fact, the slow push of the .45 cartridge in recoil makes the gun firing it much easier to handle than many lesser rounds, such as the 9mm., which characteristically kicks rather sharply.

WHICH HANDGUN?

Controversy over the revolver vs. the autopistol is the basis for much copy in the gun magazines, but for our purposes it is somewhat specious. For working-gun use, revolvers probably have a slight edge because they save their brass for reloading instead of flinging it into the nearest underbrush, and they are, in most cases, capable of using more powerful ammunition for hunting or protection against large animals than most autopistols. For defense, however, the Colt .45 auto, as modified for combat by a master gunsmith such as King's Gun Works, has no peer among handguns. It is adequately powerful, acceptably accurate, and reliable in the extreme. Learning to shoot it is much easier than a revolver, since one need not learn the somewhat difficult technique of aimed double-action fire, and it is far less likely to malfunction because of hard usage or lack of routine maintenance. Further, should repairs become necessary, they can easily be accomplished from a small spare-parts kit, usually without tools, whereas a revolver in need of fixing requires an expert gunsmith and fairly extensive equipment. Finally the .45 auto is capable of sustained rapid fire, since it can be reloaded instantly with spare loaded magazines, and the round in the chamber is available, if needed, even while the pistol is being charged with fresh ammunition. If you are tempted to believe that this feature is unimportant, I urge you to remember that "looters" is plural.

For a working-handgun, you should probably consider a Smith & Wesson, Colt, or Ruger revolver in one of the following calibers: .44 Magnum, .44 Special, .45 Colt or .41 Magnum. The .44 and .41 Magnums are not as difficult to handle as they are reputed to be if you are willing to practice a bit and, if you handload, they can be made almost gentle, yet still quite effective. I do not recommend the .357 Magnum as a primary survival weapon because it is only marginally powerful for hunting and, in order to be even moderately effective, it must be loaded to such high pressure levels that guns using those loads wear out very quickly.

The definitive book currently in print on practical handgun use is Jeff Cooper's Cooper on Handguns, and my book Survival Guns has a rather lengthy chapter on the subject.

RIMFIRES

All of the "experts" on survival who once went backpacking have decided that long-term survival under crisis conditions will be pretty much the same sort of thing. Consequently, they all seem to recommend extensive—and occasionally exclusive—reliance on .22's. My own view of the matter is expressed in a chapter of Survival Guns:

There are very few uses for which the rimfires should be considered the weapons of choice. Except for target practice and shooting pests and game which are either too large or too far away to be taken with air guns, there is very little that the .22's will do that cannot be done better with other guns. Rimfires are cheap, however, relative to centerfires and, when used with care, they can often substitute for more effective weapons under non-critical circumstances. My own strategy is to buy .22's in large quantities because they are cheap and compact, and to use them in preference to centerfires whenever the outcome of the shooting is not vital, saving my more effective weapons for occasions when they are really needed.

Among the .22 rifles, some of the modern crop of autoloaders are so accurate and so reliable that I can see no practical reason for choosing another action type. I particularly like the Ruger 10/22, the Weatherby Mark XXII (with the tubular magazine), and the ultracompact Colt Stagecoach. For specialized use in survival kits and in hidden caches, I am partial to the Charter Arms AR-7, which takes down into its own waterproof, floating stock.

If you want a rimfire pistol, look at the Walther PP or the Smith & Wesson Kit Gun for maximum quality and compactness or the Ruger auto for the best bargain.

SPECIAL PURPOSE WEAPONS

One of the most important items in this category is a suitable air rifle. Nothing else in your battery will do so much for so little cost. A first-class, modern, spring-type hunting air rifle is capable of taking a wide variety of birds and small game at ranges up to 50 yards or so, it is virtually without noise or recoil, it is incredibly accurate and very inexpensive to shoot. The very best—and probably the only one to consider, given the relative costs involved—is the Feinwerkbau F-12 Sporter made in Germany. The most practical caliber is .177 and Mt. Star Jets are the best pellets for hunting. A 4x scope specially corrected for parallax is well worth the additional cost. For a crash course in air guns, order the free catalog from Air Rifle Headquarters, 247 Court Street, Box 327, Grantsville, West Virginia, 26147, and the $1.50 one from Beeman's, P.O. Box 278, San Anselmo, California, 94960. If you need to know more, there is a chapter in Survival Guns.

Another special purpose item which you may find useful is a combination gun, such as the Savage 24C, which superposes a .22 single-shot rifle barrel over a 20-gauge shotgun. For your "emergency within an emergency" kit, it is a good choice.

If, after all that has been said here, you still feel that choosing guns for survival is a matter to be regarded with only casual interest, allow me to leave you with this parting thought. Defending your life is a competitive activity, and you cannot expect to win if either your attitude or your equipment is inferior to that of your opponent.

Mel Tappan is a survival consultant, free-lance writer, lecturer, and Survival Editor of Soldier of Fortune magazine. Prior to his present career, Tappan taught at Stanford University, served as an investment counselor and board member of several corporations, founded a bank and life insurance company, and was president of a mutual fund. He and his wife reside in California. Copyright 1976 by Mel Tappan.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Survival Weaponry."

Show Comments (0)