Financial Independence and Tax-Sheltered Investments

Only about one in 20 individuals attains financial independence in his or her lifetime. Retired people, for the most part, end up dependent on public or private charity. Many of them must continue to work their entire lives because they cannot afford to retire. Surveys indicate that 45 percent of those over age 65 are dependent on family and government for their support. Citicorp conducted a survey recently and found that as many as 70 percent of the people approaching retirement age will find it "difficult" to retire and that over one-half of those who are retired claim their pensions are barely adequate to meet minimal needs.

The responsibility for this deplorable phenomenon may be traced to two sources in particular. The government is primarily to blame for the taxes and the inflation that rob each individual of his income and savings. And the individual is to blame for not planning for his future with foresight and prudent investments.

CONVENTIONAL INVESTMENTS

The government's direct and indirect taxation has the effect of keeping the vast majority of the population struggling to stay solvent and unable to seriously put aside any money for their futures. All that most individuals can do is to buy some life insurance and save a little for emergencies or vacations.

Life insurance is fine for protecting one's family from the adverse consequences of an untimely death, but as an investment for retirement it leaves a great deal to be desired. Incorporated in a whole-life or endowment policy is a savings plan whereby "cash values" accumulate. Unfortunately, life insurance companies pay only about two or three percent on the cash value each year, among the poorest of all returns. One is far better off buying equivalent term protection and investing the savings in premiums in higher-yielding securities.

Savings accounts are also notorious for their meager returns. People put their money in banks because it's convenient and "FDIC-safe" and there are no market risks to contend with. As a retirement nest egg, however, it also leaves much to be desired. Moreover, whatever is deposited as savings is usually "hard," after-tax, dollars that end up being taxed again on the meager interest they can earn.

Those individuals who earn enough to have investment capital often make poor investments for their future needs, choosing common stocks, mutual funds, corporate or municipal bonds, or certificates of deposit. These kinds of investments have two great disadvantages: they, too, are usually made with after-tax dollars, and each fails to provide a net return equal to or greater than the rate of price inflation.

Common stocks have proven to be a poor inflation hedge over the long term. This can be seen clearly by deflating the popular Dow Jones Industrial Index for price inflation. It shows that the key stock market averages are actually no higher, in terms of real purchasing power, than they were prior to the crash of '29. Since most mutual funds do not perform much better than the stock market averages, it is safe to say that the same holds true for them.

Bonds provide a fixed-income investment that is very sensitive to fluctuations in interest rates. Corporate bonds therefore will tend to yield whatever the going rate for borrowing money happens to be. The safer the bond, the lower the yield, and vice versa. It is very difficult, therefore, to receive a sufficiently high after-tax return to offset the loss of purchasing power due to inflation. Moreover, income from corporate bonds is taxable.

Certificates of deposit offered by commercial banks and savings and loan associations are less attractive than straight savings accounts, except that they tend to offer a higher yield. But in order to receive the higher yield, control of the money must be given up for from four to six years. Since severe penalties are imposed for withdrawing funds prematurely, liquidity is sacrificed with the purchase of long-term CD's.

The best investments provide safety, liquidity, flexibility, a hedge against inflation, and a shelter from taxes. Although some of the above conventional investments may be safe or liquid or flexible, none of them are an inflation hedge or a tax shelter. It is the purpose of this essay to demonstrate that there are ways, however, to plan good long-range investments.

SPECULATING VS. INVESTING

Perhaps at this point it would be helpful to clarify the distinction between investing and speculating. To invest is "to put money to use by purchase or expenditure, in something offering profitable returns, especially interest or income" (emphasis added). To speculate is "to buy and sell commodities, stocks, etc., in the expectation of profit through a change in their market value…" (emphasis added).

An investment is predicated on receiving interest or income from it. A speculation, on the other hand, is predicated on profiting from appreciation or capital gains. With that distinction in mind we can dispense with "investment" opportunities for getting rich quick or seeing us through the apocalypse. Long-range investment planning precludes speculation, which is strictly for risk capital on a short-term basis.

Investments, by definition, are income-producing and usually involve fixed rates of return. They are usually of low risk and tend to generate a commensurately low yield. Speculations, by definition, produce capital gains or losses commensurate with the degree of risk incurred. A speculative investment is not likely to provide income from interest or dividends either. Gold coins, for instance, which do not generate any income, must be considered speculative because a profit will only be made with a change in their market value.

Before one is in a position to speculate, it is advisable to first establish a foundation of prudent long-range investments. A financial planning program is imperative if one values his or her financial independence and future security. At this time one of the surest and safest ways to achieve those goals is through tax-sheltered investments.

By taking advantage of tax-incentive investments, the individual in pursuit of financial independence has exceptional opportunities to finance his future with tax dollars. By avoiding poor inflation hedges and taxable investments and choosing self-directed, tax-favored retirement plans, tax-deferred annuities, and limited partnerships in drilling programs, individuals can accumulate important quantities of money over the long term.

THE PURPOSE OF INVESTING

Each and every investor is motivated by either the hope of gain or the fear of loss. It is in his self-interest to invest wisely to, above all, preserve his capital, and secondly, to preserve his purchasing power. Unfortunately, many investment decisions are inspired by fear or the satisfaction of short-range desires. Moreover, those wrong decisions are often compounded by the unwillingness to admit mistakes and take losses.

An uncompromising attitude may have its place within other realms, but it is totally inappropriate and disastrous when it comes to investing or speculating. We are engaged in the activity of trying to make money with money. That is our purpose and our only purpose for being in the markets. We have no axes to grind or predictions to abide by.

The rational investor or speculator is alert to opportunities no matter where they may arise. He or she is nimble to a fault and quick to recognize mistakes in judgment. Moreover, the rational investor doesn't fall in love with his or her investments. They are simply the means to the end: profits, income, financial independence.

Predicting the future is a tricky business. Investment advisors who urge their clients to put money into something based upon forecasts of the future economic situation are clearly dabbling in speculation. Unsure of the future, it is perhaps best to be in a position to seize opportunities as they arise, at the same time remaining secure in the knowledge that one's personal net worth to date has been partially financed with tax dollars.

SELF-DIRECTED PENSION PLANS

One of the great opportunities of the present day is the availability of tax-incentive investments for longterm financial planning. The 1974 Pension Reform Act liberalized individual retirement options both for self-employed professionals and for employees of firms that do not offer pension plans.

Each year, individual company employees who are not covered by pension or profit-sharing plans may deduct 15 percent, up to $1,500, of their taxable incomes and invest it in a tax-sheltered plan. The program is the Individual Retirement Account (IRA). At the heart of the IRA is the opportunity to put away "soft," pretax, dollars and have them compound tax-free until the employee is nearly 60 years old.

If an individual were to continue to make those $1,500 contributions to his IRA plan each year and have it all compound at eight percent per year for, say, 25 years, his or her tax-sheltered savings plan would have grown to over $123,000. Although salting away $1,500 may not seem like a great deal, there is little doubt that annual IRA contributions will be increased periodically over the years.

The only restriction on starting an IRA is that one cannot be a participant in any qualified pension plan in the year the contribution is made. There are also some limitations on how the money can be distributed and used. Payouts from one's IRA plan cannot begin until age 59½ and are taxed at ordinary income rates. Distributions made prior to that age for reasons other than death or disability incur taxes at ordinary rates and a 10-percent penalty.

One of the most promising uses of the IRA is as a vehicle for sheltering lump-sum payouts from pension or profit-sharing plans to individuals resigning or retiring from a company. For years there was no way to avoid the big tax bite. Now, as long as the funds received are deposited in an IRA program within 60 days, no tax is incurred and the funds are tax-sheltered.

For self-employed businessmen and professionals, the new pension law boosted the permissible annual contribution from a maximum of $2,500 to $7,500 for Keogh-plan investors. It also lowered the minimum contribution to $750 a year, which may prove to be of some help to self-employed moonlighters, including free-lance writers and part-time businessmen.

Funds contributed through the Keogh plan are treated similarly to those in the IRA. The investment is made with pretax dollars—up to 15 percent of one's taxable income to the maximum annual contribution. Likewise, distributions cannot be made before age 59½ without incurring penalties. As long as the funds remain in the Keogh account, they are completely sheltered from taxes.

One drawback of the Keogh plan, however, is the requirement that the individual make equivalent percentage contributions to a Keogh plan for his or her full-time employees. Specifically, anyone who works 1,000 hours or more a year for a Keogh investor and has been on the payroll for at least three years is entitled to a retirement plan contribution by the employer equal, as a percentage of income, to the employer's own Keogh contribution.

Keogh differs from IRA in another respect. The deadline for annual contribution is not December 31, as with the IRA, but the last income-tax filing day of the subsequent year. Now the self-employed individual has an additional three and a half months to determine how much to contribute by April 15. Of course, if the individual is sure of his or her potential earnings, the Keogh contribution can be made at the start of the year in order to pick up a full 12 months of tax-sheltered earnings.

Although both of these self-directed retirement plans have maximum limits for tax-deductible contributions, contributions may also be made to the plans with after-tax dollars. Of course they may be withdrawn, in whole or in part, at any time, without penalty, although the funds earned on that money must remain in the plan

Effective this year, Keogh-plan participants may also adopt a new "defined benefit" pension plan to assure a specific lifetime yearly income level beginning at retirement. It will now be possible to deduct and invest more than the $7,500 limit if one subscribes to the "defined benefit" formula.

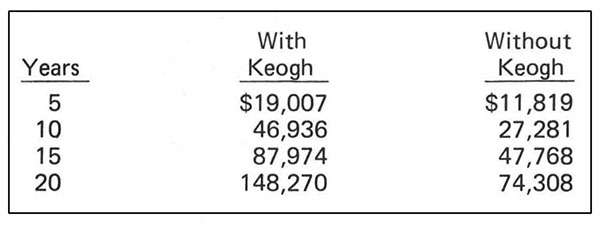

In any case, the individual with a Keogh plan has an excellent tax shelter. To illustrate the tremendous difference in accumulated sheltered growth with "soft" dollars, assume a situation with two professionals, each in the 32-percent bracket with a $20,000 earned income. The one with Keogh contributes $3,000 to his plan each year (15 percent of $20,000) and deducts it from his taxable income. He saves $960 in taxes and has his $3,000 working for him, sheltered from taxes, during the accumulated period. The professional without Keogh pays taxes on the $3,000 and invests the after-tax amount of $2,040 without a shelter. Assuming a constant 8-percent growth rate, a regular annual $3,000 contribution or $2,040 investment, and a 32-percent tax bracket, the contrasted growth of wealth is very significant.

TAX-DEFERRED ANNUITIES

One of the most effective tax-shelter vehicles for the long-range investor is the tax-deferred annuity. It is a fixed-income investment that is not subject to market risks. The principal is guaranteed, so the investor will never get back less than he or she invests. This is so because of the contractual obligations of the insurer and the safety afforded the investor in a legal reserve life insurance company.

Individuals may enjoy the full benefits of compounded growth free of taxes until liquidation or annuitization. All taxes are deferred while the funds are accumulating. Nevertheless, the investor can make partial withdrawals up to the permissible limit free of tax liability. Because a tax-deferred annuity is an insurance instrument, there is no "constructive receipt" until actual earned income is withdrawn from the plan. Amounts received upon partial withdrawal are considered a return of one's original investment, thus no taxes are incurred.

One of the outstanding tax advantages of such annuities involves death benefits. The beneficiary named in the contract receives all the proceeds—original investment plus all earnings—tax free. This is due to the "stepped-up cost basis" provision of the annuity, which means that one's accumulated wealth can pass on to beneficiaries free of taxes and probate costs.

Tax-deferred annuities are a long-term investment, but they are also highly liquid. The investor can surrender the entire contract and convert it all to cash virtually on demand. Of course, one would incur a heavy tax liability if that were to happen, but it may be done at any time. One is never "locked-into" an annuity investment during the period of accumulation.

In addition, tax-deferred annuities offer other useful options. They may be used as collateral for loans at 90 to 100 percent of their current value. They may also be used as the vehicle for rolling over a pension or profit-sharing plan for a terminating employee who would like to avoid paying taxes on the proceeds.

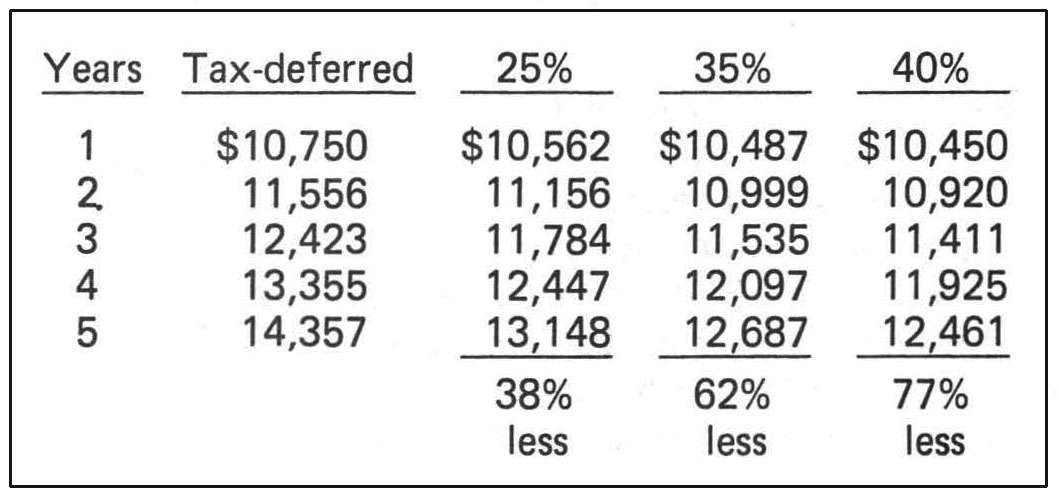

In sum, the tax-deferred annuity is one of the most attractive investments at this time. It is safe, liquid, flexible, tax-sheltered, and generates a high effective return to provide somewhat of an inflation hedge. With a current yield of 7.5 percent, the tax-deferred annuity provides real returns of 10 percent in a 25-percent tax bracket, 11.5 percent in a 35-percent bracket, and 12.5 percent in a 40-percent bracket.

In contrast with taxable investments of equivalent yield, the differences are clear. At 7.5 percent compounded on either investment, the table below illustrates for several tax brackets how much more money accumulates by choosing the tax-deferred annuity plan in lieu of a certificate of deposit, for instance, on a $10,000 lump-sum investment.

For those who do not particularly care for fixed-income investments but like the idea of a tax-deferred shelter, a variable annuity provides the possibility of capital gains and the flexibility of switching back and forth from fixed to variable. Without tax liabilities or new sales charges, the individual investor in the variable annuity can split up his contract so that half is fixed income and half is capital-gains-oriented, or it can be 100 percent fixed or variable.

With the variable annuity contract, funds are placed in a diversified, professionally managed, portfolio of common stocks designed for long-term capital growth. The shrewd investor has the option of timing his swings from the fixed to the variable depending on such factors as trends in interest rates, price inflation, and industrial production.

In any case, all of the earnings accruing in the annuity contract are tax-deferred even though the investor may make periodic withdrawals. No taxes have to be paid on interest or dividends until he or she actually withdraws them. But based on the first-in, first-out provision, no taxes would be paid until withdrawals exceed the original investment.

PERSONAL INVESTMENT ANNUITIES

For those individuals who like a tax-deferred investment but do not care for a fixed-income contract or a managed stock portfolio, there is the investment annuity. With this instrument, investment management of the assets in the account remains in the hands of the individual investor.

Assets contributed to the investment annuity are limited to what the insurance company itself can invest in, such as stocks, bonds, certificates of deposit, commercial paper, bankers' acceptances, Federal government obligations, and term life insurance. While interest and dividends are sheltered from taxes, capital gains are not.

In addition, if securities already owned by the investor are to be included in the investment annuity, any accrued capital gains or losses are realized, for tax purposes, on the date of transfer to the custodial trust company. Contributions to the investment annuity are not frozen, however. Changes and withdrawals may be easily made. And to the extent that the funds withdrawn do not exceed the cost basis, they will not be taxed.

In sum, the investment annuity is a good means of getting a very high fixed income and at the same time sheltering it from income taxes. For instance, it is possible to invest in corporate bonds or utility stocks yielding over 10 percent, place them in the investment annuity, and double your original investment in less than nine years. At the same time, you will be free to make withdrawals with no tax consequences. This way it is feasible to get effective returns in the neighborhood of 12 percent even in a 25- or 30-percent tax bracket.

OIL AND GAS DRILLING SHELTERS

Another attractive area of tax-incentive investments is the field of oil and gas drilling. Since a significant portion of the cost of the investment is financed through tax savings, investors are able to expand their investment exposure through the use of dollars that otherwise would have been paid in income taxes.

Tax-sheltered drilling programs offer investors direct participation in oil and gas exploration and development. In light of the economics of the energy supply and demand situation, petroleum operations provide a very favorable investment climate. Although there is a relatively high degree of risk associated with drilling programs, the tax benefits significantly reduce the risk through the generation of tax savings.

It is estimated that approximately 385 billion barrels of oil and 1,200 trillion cubic feet of gas remain to be discovered. About one-half of these reserves are believed to be located in the continental United States (on-shore) where most drilling programs operate. The potential for the United States to add significantly to its current reserve position is clearly tremendous.

A limited partnership in a successful drilling concern provides a good, timely investment with excellent tax-shelter benefits. As much as 90 to 100 percent of the cost of the investment may be deductible in the year in which the investment is made, and additional deductions may be available in subsequent years. Secondly, the income generated from producing wells is partially sheltered through the depletion allowance. Thirdly, if the investor chooses to sell his limited partnership, the taxable gain will probably be taxed at long-term capital gains rates.

Business and professional corporations can make use of limited partnerships in oil and gas drilling, too. Besides providing an immediate tax benefit and a means of diversifying, a drilling program can also help avoid the lash of the accumulated earnings tax. In addition, for corporations with capital losses unused (vis a vis taxes) and no immediate prospects for capital gains, the drilling program will perhaps provide a gain with which to offset the capital loss.

A tax shelter should first be a good investment. Good drilling companies have proven performance records, such as good management, profitable production, generous distributions to the limited partners, a good percentage of productive wells, and a healthy inventory of drilling equipment and undeveloped leaseholds. If the general partner has a significant investment in the drilling program, even better. There are a few very good drilling concerns, but there are also a great many that are not. Consult someone who knows.

Long-range financial planning is possible via tax-sheltered investments. There are ways to build toward personal financial independence by taking advantage of the built-in incentives to use tax dollars. This approach may be scoffed at by apocalyptics who think that any long-range investment planning is foolish. But my reply would be that it is also foolish not to seize opportunities as they arise…whatever the future may bring.

Ray Pastor is an investment executive in a Florida office of a major New York investment banking firm. He was a commodity futures specialist during his tenure in New York and since transferring to Florida in the middle of 1975 he has become a financial planning and tax-shelter specialist He has degrees in finance and international relations. In recent years, he was involved in the precious metals and currency futures markets. Ray is currently the chairman of the Libertarian Party of South Florida.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Financial Independence and Tax-Sheltered Investments."

Show Comments (0)