A Primer on Foreign Currency Trading

Foreign exchange is the currency of nations other than one's own and includes in its definition the process of transactions transferring ownership of one currency to another.

The history of foreign exchange dealings begins in ancient times. In medieval times, the European trade fairs began to draw participants from various nations. Most fairs would find a broker willing to buy and sell the various currencies at varying rates usually dependent on the simple law of supply and demand, flavored with a little of the "whatever the traffic will bear." Another novel and interesting idea was also being brought to fruition at these meetings—the idea of a futures contract, a commitment to buy or sell a commodity at some time in the future—in this case, upon the occasion of the next fair. This idea lent itself equally well to the business of dealing in foreign exchange and thus was born the forward or futures market in foreign exchange.

The job of effecting these transactions fell to those institutions capable of holding and handling large sums of money, the banking community. The banking business, however, realized the necessity and advantage of having an anonymous middleman to handle the transaction. So the trading of foreign exchange by banks came to be handled by a number of forex (foreign exchange) brokers. Each major financial center has its brokers and banks all dealing forex by phone or by cable. There are a few exceptions, such as in Europe, where centralized market places are also used. In the United States, the International Monetary Market (IMM) in Chicago is a centralized public foreign exchange market.

The market price for one currency denominated in terms of the currency of another nation has been derived by various means over the past 100 years. We will briefly cover some of the various systems used.

In the 19th century, currencies of most countries were backed by a monetary metal, either gold or silver, or in some cases, both. These metals were used as backing because they represented "store of value" money; i.e., the commodity metal was relatively difficult to procure and its scarcity maintained its value at relatively stable rates. This stability of the monetary metal lent stability to the currency it backed. The occasion of new finds of gold and/or silver were generally the only threat to the stability of the reserve metal.

The value of almost any currency could therefore be expressed in terms of a quantity of the metal or in terms of another currency whose value was denominated in terms of the monetary metal. A country was said to be on the "gold standard," "silver standard," or using a "bimetallic standard." Rates of foreign exchange were relatively stable until various economic pressures (to be discussed in detail later) brought about an adjustment of the rates between one currency and another.

The gold standard dominated the world throughout the late 19th century but was suspended during the First World War as nations resorted to embargoing gold. War costs were financed by the printing of fiat money and efforts to restore the gold standard after World War I laid the seeds for the depression of the thirties. Germany underwent a massive printing press inflation which saw the foreign exchange value of the postwar reichsmark fall to almost nothing. France, dependent on German reparations payments to pay off war debts, also suffered a decline in the value of the franc.

During the depression, with its concomitant deflation in prices, President Roosevelt strived to help domestic farmers by devaluing (see definitions) the dollar. The dollar had previously been expressed as 1/22 of an ounce of gold (i.e., one ounce of gold cost $22.00). Roosevelt changed the gold value of the dollar to $35.00 an ounce. The intended effect was to make American agricultural products more competitively priced in world markets and thus increase exports of such products. Helping the farmer was expected to be the first step in getting the economy going again. The result was a world-wide flurry of competitive devaluations as each country sought to derive an advantage over its trading partners through a change in the exchange value of its currency. Years later, the American President was to find that exporting men and war machines had a more profound effect.

During the latter part of World War II, financial leaders of the world met at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire to work out a new monetary system. Based on the U.S. dollar, the system allowed for convertibility of currencies into gold via the dollar. All currencies were thus indirectly convertible to gold. The U.S. agreed to buy and sell gold to foreign central banks (only) at $35 an ounce, plus or minus a small service charge. The exchange rate of all other currencies were then denominated in dollars at certain fixed rates. A variation in the exchange rate of plus or minus one percent adjustment was allowed to compensate for economic variables, such as balance of trade and balance of payments deficits or surpluses. The system was based on the newly established power of the United States and the U.S. dollar and was to last for over 27 years.

Under the Bretton Woods agreement, if, for example, the Swiss franc central rate was $.23, the SwF would be allowed to fluctuate from $.2277 to $.2323, a one percent variation either side of the central rate. If the Swiss were experiencing difficulty in their balance of payments, it might be that the exchange rate for Swiss francs would decline in dollar terms. In other words, there would be less demand for SwF and the dollar cost would decline. If it declined to $.2277, then the central banks would intervene in the foreign exchange market, selling foreign exchange and buying Swiss francs in order to prop up its exchange value.

Conversely if the Swiss economy were strong while the U.S. economy was weak (relatively), then the dollar cost to buy SwF could conceivably move to the upper end of the intervention band. In that instance, the U.S. dollar would be supported and SwF sold at the $.2323 level. If economic pressures were significant, and intervention failed to have the desired result, then a major readjustment of the central rate would be made.

If, as in the first example, it were the Swiss economy in trouble, the rate for SwF might be lowered in dollar terms, say to $.20. This would be a devaluation of the franc and a revaluation of the dollar. In the second example, the adjustment of the Swiss franc in dollar terms from $.23 to $.26 was a revaluation of the SwF and a devaluation of the dollar.

DEMISE OF BRETTON WOODS

At its inception in 1944, the Bretton Woods agreement found the United States dollar liabilities roughly in balance with its reserves. Throughout the fifties and sixties, however, American foreign aid generally outpaced the growth in reserves. Since 1950 (excepting 1958) the U.S. has run payments deficits (see balance of payments under Definitions) every year up to and including the present. 1959 saw the growth of foreign liabilities begin to outrun reserves at a quickening pace. In later years, the gold reserve requirement would be lowered from 40 percent to 25 percent, and finally removed completely. The U.S. and thus the world was moving from a dollar-exchange system to a fiat money system. During the sixties, foreign nations began to ask for gold in exchange for their dollar holdings. Our gold reserves dropped from a high of $24 billion in 1958 to a low of $10 billion in 1970. The U.S. continued to expand its money supply and inflation brought with it the specter of a depreciating dollar.

Efforts to restore stability in 1967 through the formation of a gold pool and a two-tier system for the price of gold managed to buy some time but ultimately dissolved in failure. The U.S. was forced to close the gold window and would not exchange gold for dollars. The dollar was no longer as good as gold.

Ultimately the U.S. was forced, by continuing huge payments deficits and indeed even a trade deficit (the first in over 70 years), to devalue the dollar in terms of gold. The Bretton Woods system would be quietly laid to rest and a new system, The Smithsonian Agreement, would restore monetary stability to the world. But it never did.

The Smithsonian was put together with a new set of central bank rates and a wider intervention band of 2¼ percent above or below the central rate, and a new gold price of $38.00. It was to last less than a year. At the same time that the world was opting for a 4½ percent band, the European economic community (EC) elected to keep their currencies with a narrower band of 2¼ percent (plus or minus 1-1/8 percent) vis-a-vis each other.

While the United Kingdom (UK) unofficially tried to maintain itself within the EC band (which came to be known as the European Snake) the sterling-dollar central rate appeared to have been misconceived at $2.60 per £. In June 1972, after a brief attempt at intervention, the Bank of England allowed sterling to float. The pound quickly sank, like a rock, from $2.60 to $2.42. Sterling has floated ever since, bobbing on the monetary sea, from $2.42 to $2.52, sinking to $2.32, rising to $2.35 and of late, sinking again, this time to $2.1750.

Later that same year, the rush to dispose of inconvertible dollars into more stable currencies would bring about pressure on the European nations and Japan to repeg their rates to the dollar at new levels. The Swiss franc and mark revaluations (see definitions) occurred in the fall and marked the beginning of the end for the Smithsonian. Death occurred at the occasion of the second U.S. dollar devaluation in February 1973. At that time, the currencies of most major nations were floating; i.e., while central bank rates were still defined, there was no longer any formal agreement to intervene, vis-a-vis the dollar, at some specified level. Instead informal intervention might occur at some arbitrary rate, decided, oft times unilaterally, by the central bank of a nation. This was referred to as a "dirty float." The EC Snake, however, was restructured and the Europeans continued to maintain their rates vis-a-vis each other, intervening and revaluing or devaluing as might be required. The exceptions were the pound sterling, which still floats, and the Italian Lira, which is a two-tier float. Other EC nations also have two-tier currencies.

SOME FUNDAMENTALS OF FOREIGN EXCHANGE

All of the above movement in exchange rates has occurred in the various world markets for foreign exchange in response to economic functions. These fundamentals include trade balances, political and social factors, government budgets and expenditures (fiscal policy), money supply and interest rates (monetary policy), and payments balances (trade and capital surpluses or deficits combined). In noncrisis periods, the most sensitive fundamental is that of interest rates, as these affect the flow of funds from country to country, seeking the highest return. Expectations of changes in direction (anticipation) also affect the market both in spot and forward dealings. For example, if the British pound sterling were under speculative selling pressure because of social unrest, labor strikes, and concurrent terrorist attacks, one might anticipate that the Bank of England minimum lending rate would be increased a percentage or so in order to attract sufficient inflow of funds, seeking the high interest, to offset the outflows attributable to the bearish fundamentals. However, boosting the interest rate will only firm the spot. Forwards will decline under the speculative pressure as well as forward hedge selling by those moving into British debt instruments.

As another example of interest rate functions of spot and forward exchange, the Mexican peso forward market has always been at a discount to spot because Mexican financiera note yields are significantly higher than U.S. rates. Investors buy spot pesos, invest in the financieras at 10-11 percent per annum, and then look to hedge their investment and return by selling in the forward market in order to cover their exchange risk. If the discount is only 1-2 percent, then the hedge investment will return 8-10 percent. If the discount is greater, then the investor may be reluctant to invest in an unhedged instrument. Barring expectations of a Mexican peso devaluation, forwards would then rise to the level of a 1-2 percent discount.

During the monetary crisis of 1971-73 when speculation against the U.S. dollar caused inflows of capital into Swiss francs, deutsche marks, and Japanese yen, these countries reduced their interest rates to very low levels (Switzerland even went to a negative rate) in order to discourage such inflows. Under normal circumstances, if another country had a lower interest rate than the U.S., then forwards for those currencies ought to be at a premium to the spot quotation.

ANALYZING THE FUNDAMENTALS

Proper analysis of the fundamentals is a necessary prerequisite for the speculator in foreign exchange. What is less widely understood is the need for importers, exporters, and corporate treasurers of multinational concerns to include fundamental analysis in their planning. Product pricing without consideration of the exchange risk can result in what was originally a profitable deal becoming less profitable or not profitable at all.

The first fundamental of importance is interest rates. However, the impact of interest rates on exchange rates is most significant only in times of normalcy. In other words, in times of monetary crisis, interest rates assume less significance.

Of further importance are the balance of trade, capital flows, balance of payments, G.N.P., government budgets, fiscal and monetary policy, and monetary reserves. Let us review each to see how they affect exchange rates.

Balance of Trade—If a country imports more than it exports, then there will be a net outflow of its currency. As the supply of its currency increases, the value will decrease, as in any other supply and demand situation. If a country is a net exporter of goods, there will be demand for its currency to pay for its goods. Germany and Japan are good examples of this latter case, running up large trade surpluses for many years.

Capital Flows—If a country is a net importer of capital it will have a capital flows surplus. Oft times, a nation that is a net importer on trade (a balance of trade deficit—capital flowing out in payment) will have investment capital flowing in to balance the trade deficit. If one balances the other, then this would make for a balance in the overall account of the country, which final figure is referred to as the balance of payments.

The balance of payments, which is roughly the trade deficit or surplus and the capital flow deficit or surplus added together, indicates the financial standing of a country. It is a key factor in the stability of the exchange rate. The U.S., for example, ran balance of payments deficits for years and was finally forced to devalue. Running capital flow deficits for years (and even a trade deficit in 1972) caused a loss of monetary reserve in the form of gold. When our reserves of gold had been drawn down to a level considered minimal for military protection, the outflow of gold reserves ceased and the dollar was devalued. Similarly, in the case of Japan, its history during the sixties had been one of trade surpluses, increasing reserves, and an eventual revaluation. After the two devaluations, Japan took its reserves, which consisted mainly of American dollars, and used these reserves for purchases of goods, such as American soybeans and pork (which caused a decline in their trade surplus), and used reserves for capital investment, such as buying the State of Hawaii, parts of California, and American stocks and companies. This caused a huge loss of reserves and a balance of payments deficit, which in turn, necessitated a depreciation of the yen. Currently, because of the oil crisis, Japan and Germany, for example, will be faced with higher energy costs. This will, in turn, cause higher import prices and will cause the balance of trade to decline to a smaller surplus, or even to a deficit, and will adversely affect their reserves. In order to retain reserves and remain competitive in world markets, these countries would be willing to devalue their currencies. The net result of higher oil prices will be a world-wide balance of payments deficit by the industrial oil-using nations and conversely, huge balance of payments surpluses by the oil-producing nations. The oil users will resort to competitive devaluations to offset the higher oil prices and save reserves. After a while, it will be the Arabs buying Hawaii from the Japanese!

Gross National Product—If a country were to increase its productivity, then it should be expected that its goods would become more competitive in world markets and its balance of trade and payments improve.

Government Budgets—Fiscal policy can affect exchange rates insofar as the funding of government expenditures has an effect on the domestic economy. Raising taxes to pay for government spending decreases spending in the private sector while monetization of the debt by inflating the money supply increases the likelihood of higher prices and diminishes the probability of good trade figures.

Monetary Policy—Attempts to improve a country's external account are usually done at the expense of its domestic economy. For example, if interest rates are raised in an effort to encourage capital inflows and stabilize the exchange rate, it will also have the effect of slowing down business domestically. Declining business activity will lower prices until such times as they become attractive in world markets. World demand improves the trade figures; business activity increases again and the cycle goes on.

Monetary policy includes the utilization of changes in the discount rate and expansion or contraction of the money supply.

SUMMING UP THE FUNDAMENTALS

In review, individuals should keep abreast of the following statistics and review the relative difference between them in order to assess possible exchange rate changes:

General

Interest Rates

Money Supply

Monetary Reserves

Domestic Account

Wholesale Price

Consumer Prices

Gross National Product

Government Spending

External Account

Balance of Trade

Capital Flows

Balance of Payments

UNDERSTANDING THE QUOTATIONS

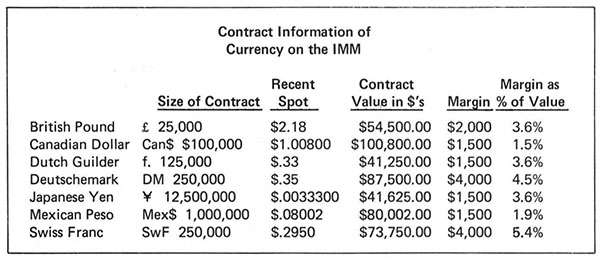

The cost of one currency in terms of another is referred to as the exchange rate. The rate can be expressed in terms of either currency. On the IMM and in U.S. forex markets, foreign currency is generally denominated in U.S. dollar terms. For example, a recent quote for British pounds was $2.1790-$2.1800. This meant it cost $2.18 to exchange (purchase) one British pound while one could sell one British pound and receive $2.1790.

Likewise, the quote for one German mark (deutsche mark) was $.3500-$.3510. In other words, if you were purchasing DM's, you would pay 35 and 10/100th cents per DM. If selling DM's, you would receive 35¢ for each. Similar recent quotes for IMM currencies are as follows:

Swiss Francs = $.2950 (29½ cents per SwF)

Dutch Guilders = $.3300 (33 cents per f.)

Japanese Yen = $.0033300 (1/3 cent per yen)

Canadian Dollar = $1.00800 (one dollar and 8/10th of one cent per Canadian dollar)

Mexican Peso = $.08006 (eight and 6/10000ths cents per Mex $)

Likewise, the above exchange rates can be quoted in terms of the other currency. This is referred to as the reciprocal. For example:

$.0033300 to the yen = 300 yen to the dollar

$.08006 to the peso = 12.49 Mexican pesos to the dollar

$.2950 to the SwF = 3.3890 Swiss francs to the dollar

$.3500 to the DM = 2.8570 deutsche marks to the dollar

$.3300 to the f. = 3.030 guilders to the dollar

Transactions in forex fall into two categories, those for immediate delivery (spot) and those for delivery at some time in the future (forwards). In actuality, spot transactions involve a one day delay for North American currencies and a two day delay for EC currencies and the Japanese yen. For example, spot Canada or Mexican peso quoted today is for delivery the next business day while spot today for DM, SwF, guilders, £, and yen is for delivery two business days hence. This delay reflects the time needed to effect cable transfers and handle the necessary paperwork. Quotations for forwards are expressed in terms of a discount or premium to spot.

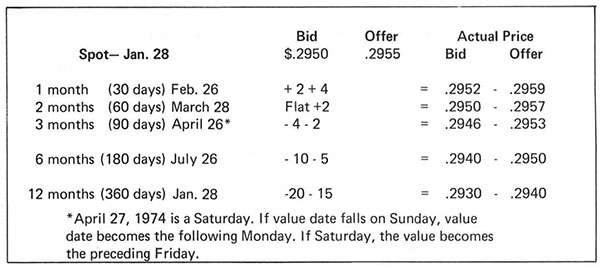

Example: Today is Thursday, January 24, 1974. The value date for spot Swiss francs would be Monday, January 28. Forwards are quoted for 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months forward, in 30 day increments.

The bank forward market is therefore primarily dealing on a monthly basis from the spot value date. The IMM uses a different system. Contracts are standardized, with the value date being the third Wednesday of the month, on a quarterly basis. For example:

1974

March March 20

June June 19

Sept. Sept. 18

Dec. Dec. 18

1975

March March 19

June June 18

THE FUNCTION OF THE ARBITRAGEUR

It is at this point that the arbitrageur enters the picture. He is the conduit between the inter-bank market and the IMM. The arbitrageur takes the bank rate for the day and interpolates the forward swap for the value dates used on the IMM. In this manner, he can bid or offer on the IMM at a few points difference from where the bank will deal. The IMM is therefore always relatively close to rates in the international forex bank market. For example, if the arbitrageur were making a market on the IMM for the June Swiss franc he would take the three month forward swap -4-2 and the six month -10-5 and would compute for his value date, June 19. The difference between the three and six month bids is -6 (-4=10=6). June 26 is 60 days beyond the three month so June 19 is 60 minus 7 = 53. There are 90 days between the three and six months so June 19 bid is 53/90ths of -6. This sum, 3.53, is added to -4 to equal -7.5. The offer side for June 19 is 53/90ths of -3 added to -2 or 3.7.

Therefore:

Spot .2950-55 Bid Offer

June 19 -7.5 -3.5 = .29425 -.29515

The arbitrageur on the IMM would bid at a price below .29425 and offer above .29515. If his bid is hit, he will immediately sell a like quantity of this same value with his bank. Competition between arbitrageurs will, in time, make their rates very close to the bank rate. If a public market such as the IMM develops a wide participation (as is happening) rates will equal or better those of the bank market, and will eliminate the arbitrageur completely.

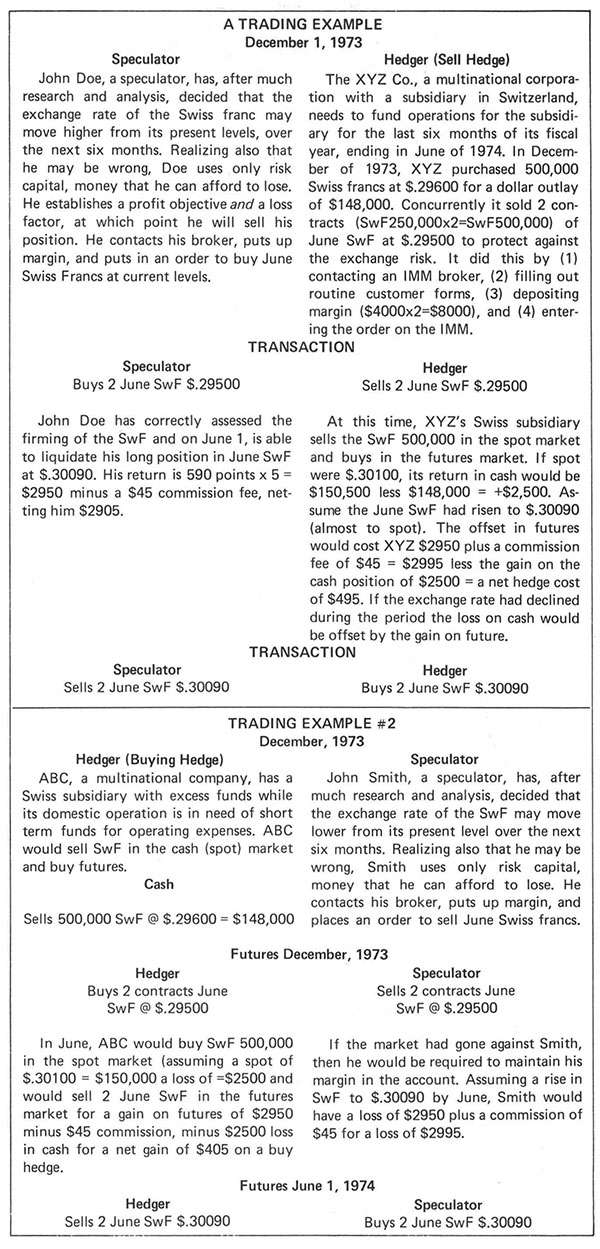

It can be seen then that analysis of fundamentals in foreign exchange as an indication of exchange rate direction must also be modified by the application of information derived. The response of a speculator and hedger to sundry indicators may vary each according to his needs.

As in any other marketplace, supply and demand are determined by complex subjective factors, to best serve the needs of each trader. Hopefully, this article has succeeded in removing the mystery from the foreign currency marketplace.

Lawrence C. Sarsoun began his career in finance in 1960. In 1966 he published his first manual on commodity trading and began writing a weekly analysis of the egg futures market for Hayden Stone, Inc. In 1972, he became a member of the International Monetary Market and was made manager of Heinold Commodities' IMM division. He has authored the "Foreign Currency Futures Handbook" and produces a weekly newsletter on the IMM and foreign exchange markets.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "A Primer on Foreign Currency Trading."

Show Comments (1)