The Great Electrical Equipment Conspiracy

Undoubtedly the most celebrated price fixing antitrust case of modern times is the electrical equipment manufacturers price conspiracy, decided in 1961 (1). Involved were some of the nation's largest and most prestigious firms, such as General Electric, Westinghouse, Allis-Chalmers, Federal Pacific, I-T-E Circuit Breaker, Carrier, and many others. The charges: that various employees of said firms had, between 1956 and 1959, combined and conspired to "raise, fix, and maintain" the prices of insulators, transformers, power switchgear, condensors, circuit breakers, and various other electrical equipment and apparatus involving an estimated $1.7 billion worth of business annually. (2)

A series of Philadelphia grand jury indictments was returned during 1960. After much discussion between the defendants and the Department of Justice, the firms were allowed to plead guilty to some of the more serious charges, and nolo contendere to the rest. On 6 February, 1961, Judge Ganey sent seven executives off to jail, gave 23 others suspended jail sentences, and fined the firms involved nearly $2 million. Subsequent triple damage suits brought against the equipment manufacturers by the TVA and private firms that had been "overcharged", increased the financial penalty manyfold. And so ended the most publicized price conspiracy in all business history.

INDISPUTABLE EVIDENCE

The fact that there were price "meetings" among various electrical equipment producers between 1956 and 1959 was indisputable. The meetings were a "way of life" in the industry. (3) Some of the meetings were little more than hastily called "gripe" sessions where the various firm representatives complained about price discounting and foreign competition. But others were more sophisticated and, apparently, involved the determination and application of secret bidding formulaes and the allocation of market business. Certainly the most incredible aspect of the conspiracy was not the price meetings but the absolute disclaimer by top General Electric and Westinghouse brass of any knowledge of any "conspiracy." The executives actually involved in the meetings took the thrust of the financial and social penalties.

WHAT IS PRICE FIXING?

If an "agreement" to fix prices is price fixing, then the electrical manufacturers were certainly guilty of price fixing and the issue is a dead one. Or if "tampering with price structures" constitutes price fixing, then these meetings were illegal and in clear violation of the Sherman Act. But for the purposes of this discussion the important questions are not legal (or moral) but economic. Did the conspiracy in fact "raise, fix, and maintain" unreasonable prices as the 20-odd indictments charged? Did it "restrain, suppress, and eliminate" price competition with respect to the selling of various kinds of electrical machinery or apparatus? Did the conspiracy work to "cheat" buyers of the benefits of free competition?

PRICING PRACTICES

To comprehend correctly the issue of price conspiracy, one must understand the usual and normal pricing practices in this multi-product, oligopolistic industry. General Electric, Westinghouse, and to a lesser extent the smaller manufacturers sell hundreds of thousands of electrical products that have been "standardized" to a high degree by the industry's trade association. The products are sold out of huge catalogs where potential customers may obtain a detailed description of the product and its suggested list price. Almost all of the catalog products are so-called "shelf" items which the huge manufacturers produce continuously and hold in inventory. When an order is received a computer fills the request and directs that the particular product be shipped from the closest warehouse to the customer.

IDENTICAL PRICES

Since the products produced by the electrical equipment manufacturers are almost identical, and all firms quote delivered prices, the selling prices for standardized shelf items is almost identical to all buyers. (4) Any price decrease by one seller—usually announced with a mimeographed price sheet to customers—is quickly matched by other sellers. On sealed bid business, the price cut is "announced" when the bids are opened. In any case, the pressure of the marketplace, i.e., the desire on the part of each manufacturer to keep or increase his customers, makes the new (lower) price the new catalog price, which is, again, nearly identical for all firms that want to be competitive." Although there may be recognized quality differences that eventually "sell" an order, it still appears that the price of the higher-qualified product must nearly equal its lower-qualified competitor. The testimony of John K. Hodnette, executive vice-president of Westinghouse, illustrates the pricing procedures with respect to a shelf item, here electric meters: (5)

This is a standard item. It is the meter that goes on the outside of the house that measures the use of current, protects the customer, tells the utility how much electricity has been used so that they can render a bill. We have been manufacturing these meters for 75 years. The selling price is approximately $16.…About 60 days ago, I think it was, one of our competitors decreased the price of his watt-hour meter that corresponded to the one in question in Cleveland. When we learned of this, which we do very promptly, because they send out published catalogs, and our customers call them to our attention, so with the large number that are printed it is very easy matter to get a copy of a competitor's catalog and determine his prices, they reduced the price of the meter 30 cents per meter, when the new price list came out. We had just concluded the development of a meter which we thought was superior, better than any in the industry. We advised our field salespeople that we were not at that time planning to reduce our prices. We felt that we could sell a superior product at a higher price. We very soon learned that customers would not pay us the price, and many of them came to us and asked us to reduce our price to the same as those charged by competitors, so that they could continue to buy meters from us. (6)

Thus, Mr. Hodnette argued, competition produced identical prices. And the pricing procedure was no different with reference to "sealed bid" business. As he explained:

The City of Cleveland and many other people recognize no brand preference or quality preference of one meter manufactured by one company as against another. In order to obtain business in any location, it is necessary that he be competitive with respect to price. This is total cost to the customer, whether he be the City of Cleveland or TVA, delivered to him at the site he wants it. He will not pay more.…In order for a manufacturer to get an order, he must quote a competitive price. He must quote a price that is equal to that of any of his competitors, delivered to the customer, and without any qualifications. [7]

From these remarks, it is clear that the normal forces of competition tended to produce identically quoted list prices in the electrical equipment manufacturers industry. To regard such identical quotations as per se evidence of collusion or conspiracy would be naïve and wrong. A final note on this extremely important issue from Ralph Cordiner, president of General Electric during this period, will suffice:

In the course of these hearings, considerable attention has been devoted to the frequent identity of prices charged by competitors. It has been suggested that this identity, where it occurs, indicates a lack of competition, or even continuing conspiracy, among competing manufacturers. In all candor, may I say that identity of prices on standard, mass-produced items normally indicates no such thing. On the contrary, such price identity is the inevitable and necessary result of the force of competition—a force that requires sellers of standardized items to meet the lowest price offered in the market. The manufacturer who makes a product on a mass-produced basis and where minimum performance or quality standards are a part of the customer specifications will not long be in business if he prices that product above the market. The customers will purchase elsewhere unless his product has demonstrable additional values accepted by a reasonably large number of customers. The manufacturer who prices his products below the market will quickly discover there is no advantage to him because his competitors drop their prices to the price level he establishes…It is simply not true that uniformity of prices is evidence of collusion. Nor is it true that uniformity of prices on sealed bids amounts to an elimination of price competition. The facts are that vigorous price competition continually takes place with one effect being a uniformity of catalog prices and, therefore, a uniformity of sealed bid quotations. Suppliers come to the conclusion—some possibly reluctantly—that if they want to continue to offer a particular product for sale that they will have to offer it at market prices equal to the lowest available from any supplier of any acceptable product. (8)

NON-STANDARDIZED ITEMS

Even if the product being sold is not a standardized shelf item, firms desiring to be "competitive" tend to meet the already established price. This procedure will hold even if a firm has not as yet manufactured the specialized electrical apparatus; it will quote the price of its competitor to announce to its potential customers that it can and will be competitive if orders should appear. Thus the "costs" in the short run or even before the product is actually made, are irrelevant to price determination. Again and again, the business men that testified before the Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly pointed out that market prices were determined by the firm willing to sell at the lowest price. But again and again, many of the Senators on the committee, particularly Senator Kefauver, refused to accept that explanation. Like many economists, Kefauver implied that competitive prices should have been determined by "costs"—completely ignoring the fact that buyers of electrical apparatus have no idea what producer "costs" are and care less. Note the following exchange of views with respect to "costs" and competition:

Senator Kefauver: How does it happen that each one of these other companies comes up with exactly the same cost figures and decides what should be their price?

Mr. Hodnette: I have no idea what their costs are. The prices are determined by competition in the market place, not by cost. (9)

Or note the discussion below between Senator Kefauver and Mark W. Cresap, Jr., president of Westinghouse, with respect to the nearly identical prices ($17,402,300) submitted by different companies on a 500,000 kilowatt turbine:

Senator Kefauver:…did you arrive at that price independently?

Mr. Cresap: Yes, sir.

Senator Kefauver: You figured it yourself?

Mr. Cresap: We arrived at that particular one on the basis of fact that General Electric Co. had lowered its costs for this type of machine, and we met it.

Senator Kefauver: You mean you copied it from G.E.?

Mr. Cresap: No, we met the price.

Senator Kefauver: Have you ever made one?

Mr. Cresap: Have we ever made—

Senator Kefauver: A 500,000 kilowatt turbine?

Mr. Cresap: We had not at that time, no sir.

Senator Kefauver: Have you made one yet?

Mr. Cresap: No.

Senator Kefauver: Has G.E. ever made one?

Mr. Cresap: Yes, they are making one.

Senator Kefauver: They have never made one, though?

Mr. Cresap: Well, this is the price that they established for this machine, and we met it.

Senator Kefauver: You mean you copied it?

Mr. Cresap: We didn't copy the machine. We met the price because it was the lowest price in the marketplace.

Senator Kefauver: In other words, you copied the figures exactly, $17,402,300, from General Electric?

Mr. Cresap: Senator, we had a higher price on the machine on our former book, and when they reduced, we reduced to meet them, to meet competition.

Senator Kefauver: If you never made one, how would you know how much to lower or how much to raise?

Mr. Cresap: You would know by the basis of how much you needed the business, what the conditions of your backlog was, what your plant load was, what your employment was, and what you thought you had to do in order to get the business.

Senator Kefauver: In any event, you would not know whether you were making money or losing money on this bid, because you had never made one, and Mr. Eckert told us you had no figures on which to base this price. You just followed along with G.E. Is that the policy of your company?

Mr. Cresap: The policy of our company is to meet competitive prices, and this is the manner in which the book price on this particular machine was arrived at…

Senator Kefauver: Even if you lost money?

Mr. Cresap: Even if we lost money, if we needed the business to cover our overheads and to keep our people working…

Senator Kefauver: On something that you had never sold, had never made, and that you have not made yet, and they have not made one yet, their price is $17,402,300, the same as yours.

Mr. Cresap: They would have to be, Mr. Chairman, if we are going to be competitive. We cannot have a higher price than our competition.

Senator Kefauver: How about a lower price?

Mr. Cresap: If we had a lower price, I am sure they would meet it, if they wanted to get the business very badly. (10)

In summation, price identity may imply intense competition and a working out of the "natural forces of the market." Or it may imply collusion and conspiracy. The next section will determine what it did imply in this case.

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF CONSPIRACY

The essential question to be answered in this section is: did the electrical equipment manufacturers successfully conspire to raise, fix, and maintain prices? Did the meetings—which many executives admitted attending—actually fix the level of prices and price changes or did competition? Was the driving force behind price identity collusion or competition? The most acceptable generalization concerning the nature of the price conspiracy meetings must be that they were a failure, as one executive rather disgustedly put it, "a waste of time." Without exception, every witness queried before the Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly stated that the meetings were not effective at all. (Why they attended will be discussed below.) Because this particular aspect of the conspiracy is so important—and so neglected—it must be documented thoroughly with direct testimony. The following exchange concerns "collusion" on medium turbine sales:

Senator Kefauver: How would it work out? Just tell us how it worked.

Mr. Jenkins: It didn't work very good.

Senator Kefauver: It looks as if it has the possibilities of working good.

Mr. Jenkins: The thing that is important, this is a dog-eat-dog business and everybody wanted it. There has never been enough business. (11)

And again, Kefauver with Jenkins on the end of the price meetings on turbines:

Senator Kefauver: When did they break up?

Mr. Jenkins: In early 1959.

Senator Kefauver: What happened then to cause this cessation?

Mr. Jenkins: It was a waste of time and effort. There was very little business. We were at the bottom of a buying cycle. Everybody wanted every job, and it was of no value. (12)

The following exchange concerns price "collusion" on electrical condensors:

Senator Blakley: If I understand, then, if your competitors were of the same mind as you, then it would be a general feeling that these meetings for the purpose of fixing prices would be in order; is that the way to interpret it?

Mr. Bunch: An attempt may have been made to fix these prices, but it was entirely unsuccessful. (13)

The following exchange concerns price "collusion" on small turbine generators:

Mr. Flurry: What was decided at that meeting with respect to price level?

Mr. Sellers: This meeting consisted of perhaps—I say "perhaps"—there were six manufacturers in this small turbine generator business represented. This was recognition of the fact that the prior bid price discussions which had been going on among the manufacturers was so ineffective as to be rather useless, and to try to determine whether or not people were serious in this endeavor or whether—well, it had become so useless that there was a question as to whether you should continue, and this was a meeting to discuss that. Also, an effort to stabilize the market at some place within a few percent of a published price, rather than 10 or 15 percent, where the market had drifted. Again, the meeting was so ineffectual as far as I am concerned, because it promptly all fell apart. This rugged individual type of business that we are in simply ignored—I will put it a different way. The forces that were coming about from lack of volume and the pressure that was on a manufacturer to get volume negated any price discussion. It just did not amount to anything. (14) (Emphasis added)

The following exchange concerns meetings and alleged price collusion with respect to medium voltage switchgear:

Mr. Flurry: I understood you to say that this broke off sometime before 1959?

Mr. Hentshel: That is right, sir.

Mr. Flurry: What was the cause of that break-off?

Mr. Hentshel: Basically the thing just wasn't working. In other words, everybody would come to the meeting, the figures would be settled, and they were only as good as the distance to the closest telephone before they were broken. In other words, the thing just wasn't working. (15) (Emphasis added)

The following exchange concerns meetings that were designed to set and maintain the prices of power transformers:

Mr. Ferrall: What do you mean, Mr. Smith, when you say you did not know whether any good would come of it or not?

Mr. Smith: Well, I meant by that whether there was anything done at the meeting with competitors which would in any way improve the price situation. Past meetings with competitors had been rather unfruitful in that respect.

Mr. Ferrall: You mean you did not know whether they would abide by their agreements?

Mr. Smith: I don't know whether you can say that we had real agreement at any time…(16)

Mr. Smith: (continuing) My experience in meeting with competitors, as I have said before, indicated to me that it was a rather fruitless endeavor. It might be one day, it might be two days, after a meeting, before jobs would be bid all over the place, and there seemed to be no real continuity that came out of those meetings in the way of stabilizing prices at any level. (17)

And again with Mr. Smith of General Electric with respect to "price agreements" on power transformers:

Senator Carroll: In other words, you reached agreement that there could be some stabilization?

Mr. Smith: There could be, but we agreed upon no stabilization.

Senator Carroll: I understand that. I am not asking you to commit yourself, but there was this general agreement that you could stabilize?

Mr. Smith: General understandings that it would probably be best if it was possible.

Senator Carroll: Did you remove the threat of price cutting?

Mr. Smith: No, sir.

Senator Carroll: Was there any price cutting after that;

Mr. Smith: Surely, sir.

Senator Carroll: Did it continue?

Mr. Smith: Yes, sir…

Senator Carroll: (continuing) I think I have asked this question, but I will ask it again. Do the records then reflect that you got some price stabilization after that time? I mean, not the records, but the practice, your profits.

Mr. Smith: The price curves which were maintained by the power transformer department all the way through this whole period is one of this kind of picture, up and down all the time.

Senator Carroll: Did it improve after your last conference, the conference in 1958? Did it improve in 1958 after the two presidents got together?

Mr. Smith: No, sir, not to amount to anything.

Senator Carroll: Did it improve any in 1959?

Mr. Smith: It got worse in 1959. (18)

The following exchange again concerns price meetings with respect to fixing prices on power transformers:

Senator Hruska: By and large, Mr. Ginn, you have had considerable experience in the business of meetings with competitors. How effective were those meetings to get the job done that they purported to have as an objective?

Mr. Ginn: Senator, this is the way I will put it. If people did not have the desire to make it work, it never worked. And if people had the desire to make it work, it wasn't necessary to have the meetings and violate the law.

Senator Hruska: So that your preliminary discussions and meetings with competitors—

Mr. Ginn: Were worthless…I think that the boys could resist everything but temptation. No sir, I'll tell you frankly, Senator, I think if one thing I would pass on to posterity, that it wasn't worth it. It didn't accomplish anything, and all you end up with is by getting in trouble. (19) (Emphasis added)

And a final exchange with respect to the effectiveness of "fixing" transformer prices:

Mr. Rosenman: And you fixed prices, you participated in the fixing of prices?

Mr. McCollom: That is right.

Mr. Rosenman: Fixing of the book price—

Mr. McCollom: We discussed those in meetings.

Mr. Rosenman: But you maintain that there was no agreement as to these?

Mr. McCollom: We discussed these generally, and I say that there was no agreement, because it didn't result in prices being quoted at those levels that were discussed. There was just no evidence of any agreements in the actions that were taken by the parties in the meetings. There was no formal definite agreement in writing on this thing.

Senator Kefauver: None of it was in writing?

Mr. McCollom: There was no verbal agreement, just a discussion.

Senator Kefauver: Just a discussion of it.

Mr. McCollom: Just a discussion of it.

Senator Kefauver: Was there, or was there not, an understanding about what was going to be done?

Mr. McCollom: Well, I think the results indicate that there was no understanding.

Senator Kefauver: I am not talking about results. I am asking whether at the meeting there was an understanding about what was going to be done?

Mr. McCollom: Well there was a discussion of price levels 15% off book. I might have gone out of the meeting thinking the other people understood it; they might have gone out thinking I did; but there was no action that supported any understanding of it, that there was any understanding because it did not occur. It did not happen. (20) (Emphasis added)

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Through the entire period of the conspiracy, the firms could not suspend price competition. Although there had been repeated attempts to fix, raise, and maintain prices, the attempts rather monotonously failed. Price agreement might last a day or two and "then somebody would break the line and there would be another meeting." (21) In most cases, in fact, the prime purpose of the meetings was an attempt to restore "agreements" that were being openly and regularly violated in the marketplace. In other instances, the meetings were an attempt by some firms to "get the line on prices," i.e., to find out what a competitor might do with his price in the near future. (22) Such information would allow a firm to bid just under its competitor and secure the desired business. As Mr. Raymond Smith, former general manager of the transformer division at General Electric, put it:

…my prime objective was to find out whether the Westinghouse people had received any instructions from their people, and failing to do so, I thought the meeting was worthless. (23)

PRICE INFORMATION

Hard and fast evidence on actual prices and price changes during the period of the conspiracy is hard to uncover. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) indexes of wholesale prices show substantial increases for various kinds of electrical apparatus. Switchgear prices, for example, increase from an index number of 112.7 in 1950 to 127.4 in 1952 to 135.1 in 1954, to 154.1 in 1956, to 172.8 in 1958, and to 176.6 in 1960. (24) Since there were "meetings" with respect to the prices of switchgear—at least during the latter part of the 1950's—the impression conveyed is that prices were rather routinely raised and maintained at "unreasonable" levels.

The impression conveyed by the BLS evidence is an altogether incorrect impression. The statistics are based on catalog prices; they do not necessarily relate to the actual prices being charged in the marketplace. The fact remains that all during the "conspiracy" period, switchgear sold at particular percentages off of book or catalog price. This "discounting" was particularly pronounced during the infamous "white sale" of 1954 and 1955, when switchgear was selling for as much as 45-50% off of book. (25) This "sale" was repeated in late 1957 and early 1958 when market prices were as much as 60% off of book. (26) Ironically, the entire purpose of the switchgear meetings was to "do something" with respect to the "unreasonably" low switchgear prices. The meetings ended in failure and were abandoned before the conspiracy was discovered by the Department of Justice. There was no effective price fixing in switchgear at all. (27)

PROFIT RATES

The fact that there was no effective price fixing in switchgear, or in many other electrical products, might be substantiated by an examination of profit data for some of the firms involved during the period of the "conspiracy." Although a positive relationship between "periods of conspiracy" and "unreasonable profit" would not prove cause and effect, the complete lack of any such relationship might be indicative of ineffectual price collusion. Indeed, if price conspiracy cannot produce "unreasonable" profit levels—and, thus, generate the misallocation of resources that so concerns the economists—why is it important at all? If collusion does not generate substantial profits, economists, for at least a generation, have made mountains out of molehills.

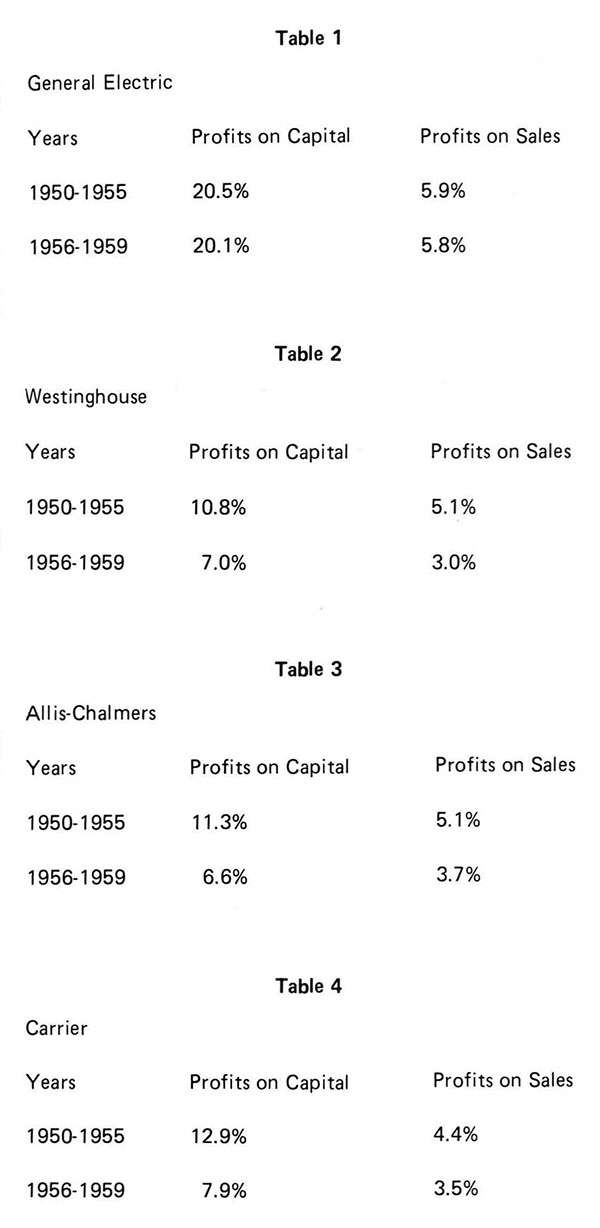

The 20 separate indictments returned by the grand jury in 1960 charged that a price conspiracy had been in effect in the electrical equipment manufacturers industry between 1956 and 1959. A comparison of the rates of return on both capital and sales for that period, with some previous period, is reproduced below for four of the most important firms involved in that conspiracy. (28)

It can be observed from these tables that in all cases, without exception, the rates of return on capital and on sales were actually lower during the period of alleged conspiracy than during the previous period. (29) If the conspiracy were successful, the price and profit behavior of the firms involved certainly does not reflect that "success." More than likely, the conspiracy was a sad failure from the start to finish.

WHY DID THE CONSPIRACY FAIL?

To gain an understanding of why the conspiracy failed, it is necessary to examine two crucial elements of the electrical equipment manufacturers industry: the industry's cost structure and the nature of the demand for electrical apparatus.

Although there are thousands of firms that produce and sell electrical apparatus and machinery—and although entry remains relatively easy—(30) the important parts of the industry are dominated by a relatively few, extremely capital intensive firms. As might be expected, these firms are rather sophisticated innovators; and all maintain substantial research and development facilities at great expense. More important for our purposes, however, is the fact that the extremely high capital intensity, and the resultant scale economies, (31) generate pressures for "selective" price cutting when demand is slow to gain volume.

The demand for electrical equipment is derived almost equally from industrial firms and electric utility companies. Since a high proportion of the total demand for electrical equipment is associated with new construction, or new generating capacity on the part of utilities, it becomes extremely sensitive to money market conditions. In addition, since it is a demand for a (postponable) producer's durable good, it can be expected to display the violent instability commonly associated with the "feast or famine" capital goods industry. Both factors foretell an extremely cyclical demand for electrical apparatus.

Given the instability in the economy and in the money markets during the period 1955-1960, and given the cost structure of the equipment manufacturers, it is not at all surprising to discover that price competition was severe and that catalog prices were not being honored. Here were expensively equipped firms with huge overhead costs hungry for a volume of business that did not materialize at existing price levels; this volume simply had to be attracted. In such circumstances price cutting was inevitable. Although there is numerous testimony to support this view, (32), the remarks of George E. Burens, former division general manager of switchgear at General Electric, are indicative of the real situation:

Everybody has their plant in shape. They have the facility. They have the organization. But they have no business. So, they are out grabbing. I think that is the thing. (33)

It was, indeed, the thing.

FURTHER DIFFICULTIES

Price fixing was also difficult because there were always competitors who did not compete on a national basis. When demand was flat or falling, electrical firms closer to potential customers might simply figure the cost of a particular job and quote a price to cover that cost. (34) Hence, price could be significantly different from national catalog prices, and "could be anywhere over the lot." In addition, there were so-called "tin makers" (firms that made "inferior" electrical equipment) that would make it a practice to underbid national competition, especially on sealed bid jobs. (35) Rarely would the non-national firms or the "tin makers" abide by any price agreement.

Further, there was the "problem" of price competition from the foreign firms. They could not be controlled directly, and they were not a part of the price conspiracy; accordingly, their pricing practices made it difficult—if not impossible—to raise, fix, and maintain prices on electrical equipment. For example, prices on certain turbo-generators were cut 20% when foreign competition entered the market, and meetings to "fix" that particular situation were "unsuccessful…quite unnecessary and very foolish." (36) The ability of such meetings to contain price competition under such circumstances was nil.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Price collusion was ineffective in the electrical equipment manufacturers industry because demand was unstable, economies of scale were substantial, competitors had different price and profit objectives, honesty and trust were non-existent, and foreign imports were (increasingly) important. Under such circumstances, a successful price conspiracy would have been nearly impossible. The Justice Department, it appears, with all its legal fuss, fines, and headlines, ended a nearly impotent arrangement. The general meaning of this article should not be misunderstood. It is not being argued here that "price conspiracy" is impossible or that such a successful conspiracy might not work an "injury" to the buyers. What is being argued is (1) that the inherent market forces in a free market make most price conspiracies completely unworkable and (2) that a sampling of the most famous price fixing antitrust cases in history has revealed that they involved such unworkable conspiracies. (37) With these points in mind, the reader is invited to draw any appropriate policy conclusions.

Prof. D.T. Armentano teaches economics at the University of Hartford. His article "Capitalism and the Antitrust Laws" appeared in the January 1972 REASON. His book THE MYTHS OF ANTITRUST, from which this article was drawn, will be published in May of this year by Arlington House, New Rochelle, N. Y. Copyright ©1972 by Arlington House.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

(1) Background information can be obtained from Richard Austin Smith, "The Incredible Electrical Conspiracy," FORTUNE, April and May 1961; John Fuller, THE GENTLEMEN CONSPIRATORS (New York: Grove Press, 1962); John Herling, THE GREAT PRICE CONSPIRACY (Washington: Robert B. Luce, Inc., 1962).

(2) Clarence C. Walton and Frederick W. Cleveland, Jr., CORPORATIONS ON TRIAL: THE ELECTRIC CASES (California: Wadsworth Publishing Company, Inc., 1964), p. 12.

(3) Ibid, p. 11. The best source of information about the conspiracy meetings is the Hearings on Administered Prices by the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly, Price-Fixing and Bid-Rigging in the Electrical Manufacturing Industry, Parts 27 and 28, 87th Congress, 1st session, April, May and June 1961.

(4) There was testimony to the effect that the Robinson-Patman Act made quantity discounts difficult. See PRICE-FIXING AND BID-RIGGING…, p. 17619.

(5) All the quoted testimony to follow in this article is taken from PRICE-FIXING AND BID-RIGGING IN THE ELECTRICAL MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY, unless otherwise indicated.

(6) Ibid., p. 17430.

(7) Ibid., p. 17431

(8) Ibid., pp. 17672-17673

(9) Ibid., p. 17438

(10) Ibid., pp. 17628-17630.

(11) Ibid., p. 16608. Mr. Jenkins was Sales Manager of medium turbine sales for Westinghouse.

(12) Ibid., p. 16614

(13) Ibid., p. 16639. Mr. Bunch was Manager of the condensor division of Ingersoll-Rand Company.

(14) Ibid., p. 16669. Mr. Sellers was manager of the turbine generator division of the Carrier Corporation.

(15) Ibid., p. 16884. Mr. Hentshel was general manager of the medium voltage switchgear department for General Electric.

(16) Ibid., p. 16961. Mr. Smith was the general manager of the transformer division for General Electric.

(17) Ibid., p. 16962.

(18) Ibid., p. 17013, 17029.

(19) Ibid., pp. 17069-17070. Mr. Ginn was vice president and general manager of the turbine division for General Electric.

(20) Ibid., pp. 17376-17379. Mr. McCollom was the manager of the power transformer department for Westinghouse.

(21) Ibid., p. 17883.

(22) Ibid., p. 17523

(23) Ibid., p. 17013.

(24) Ibid., p. 17767.

(25) Ibid., p. 16740.

(26) Ibid., p. 17103.

(27) The same conclusion might be made with respect to the prices of "large circuit breakers". See George J. Stigler and James K. Kindahl, THE BEHAVIOR OF INDUSTRIAL PRICES, (New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1970), p. 31. See also, Jules Backman, THE ECONOMICS OF THE ELECTRICAL MACHINERY INDUSTRY (New York: New York University Press, 1962), especially Chapters 5 and 6.

(28) The tables are based on figures taken from MOODY'S INDUSTRIAL MANUAL, and from PRICE-FIXING AND BID-RIGGING IN THE ELECTRICAL MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY, Exhibits 54A, B, C, pp. 17960-17961.

(29) The profits might have been lower for a good many reasons; the 57-58 recession in the economy is the best candidate. The point here, however, is that the collusion did not generate monopoly profits.

(30) The CENSUS OF MANUFACTURERS reports that there were 7,066 "establishments" in the electrical machinery industry in 1958, compared with 3,970 in 1947.

(31) Walton and Cleveland, CORPORATIONS ON TRIAL p. 13

(32) See, for example, PRICE-FIXING AND BID-RIGGING IN THE ELECTRICAL MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY, p. 16614

(33) Ibid., p. 16876

(34) Ibid., pp. 16693-16694.

(35) Ibid., p. 17472.

(36) Ibid., pp. 16945, 17061,

(37) For additional examples refer to my forthcoming book THE MYTHS OF ANTITRUST.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Great Electrical Equipment Conspiracy."

Show Comments (0)