Taxis and Jitneys

The case for deregulation

Last month in "Save our Smog," by John Ockert, REASON presented a tongue-in-cheek look at some of the problems of urban transportation and the potential of the free market for making things better. This month's cover story reports the findings of several years of research into the effects of government controls on the taxi industry. The author—one of the country's leading experts on taxis and jitneys—presents a carefully-reasoned case for the benefits of a free market in urban transportation.

INTRODUCTION

Taxicabs and jitneys offering a flexible mass transit service, approximating the convenience of an automobile, have important ramifications pertaining to the improvement of urban transportation facilities and particularly toward increasing mobility in the inner city. A brief look at the historical evolution of jitneys and taxis in America shows that unfulfilled demand for transit service exists in many American cities despite the decline in the use of traditional bus and line haul facilities. Additionally, an overview of taxi and jitney operations shows that there is a need for special kinds of flexible transit service in inner city ghettos.

Allowing jitneys and taxis to provide such needed services today would have several important effects on urban transportation systems and on the urban area itself. Jitney and taxis would provide jobs for inner city residents, fulfill a need for flexible circulation service in downtown or key commercial areas, and fulfill many unmet transit needs in the inner city.

Recent governmental programs aimed at solving both employment and transportation problems in the inner city have been largely unsuccessful. A look at these programs will show that although an attempt was made to create flexible services with some taxi/jitney characteristics, many basic assumptions about employment concentrations and job availability were found to be untrue. In addition, the organization and implementation of these services were unsuitable for their purpose.

The relatively low cost of jitney and taxi systems today and the potential adaptability of these services to tomorrow's transportation systems make them extremely useful for current urban transportation systems. Among the advantages of jitneys and taxis as an addition to current systems are the following:

- Jitneys and taxis have a very short lead-in time and can be put into operation quickly

- Jitneys and taxis can be readily added to current transit operations

- Operating costs and expenditures are relatively low

- The capital investment requirements are low and will not jeopardize the implementation of future transportation systems.

DEFINITIONS

Taxicabs and jitneys offer a very similar type of service, and they also are quite similar in their operation. In general, taxicabs are conventional, specially-decorated automobiles, picking up one or more passengers at one location and leaving these passengers at one or more destinations. In their most common usage, taxis travel in a one-origin to one-destination mode. Taxis generally operate on a meter-computed distance fare along random routes. Although originally a free enterprise operation, the current ownership and operation of the taxi industry varies from city to city, as will be discussed.

Jitney service refers to a type of service, not to a particular kind of vehicle, although traditionally, jitneys have been small, 8 to 12 passenger vehicles. Jitneys in America are generally individually owned and operated, and driven along relatively fixed routes, usually for a flat rate per passenger but sometimes on a zone-rate passenger fare. Jitneys usually do not have a scheduled headway* but do operate within fixed time limits during the day. Jitneys generally serve as a many-origin to many-destination travel mode. Originally, the jitney operators in America were truly free enterprise entrepreneurs, operating exactly as they pleased along whatever route they deemed profitable. Today, the few existing jitneys usually operate under some form of municipal or state regulation, but most of the scheduling and other organizational questions are settled by the owner-drivers themselves through jitney associations.

HISTORICAL EVOLUTION

Jitneys were once far more common on American streets than taxis currently are. The first American jitneys probably appeared in Los Angeles about 1914. These so-called "five-cent cars"—jitney meant a nickel, hence the term—rapidly became popular and their use spread throughout the United States, particularly in the western United States. Their great popularity and high patronage has been attributed to a number of reasons, among them: the desire to ride in a high-status vehicle, the desire for a faster ride than provided by the trolley, the desire to go to destinations not served by the fixed-rail trolley. A most telling point is that although the jitney charged about the same fare as the trolley, the total earnings of the jitneys were found to be considerably in excess of what the trolley lost to them.[1] Clearly the jitney provided a flexible and convenient service demanded by riders but not provided by the trolley.

Trolley companies across the country reported huge losses due to the competition offered by the jitney[2]; the Los Angeles trolley company estimated a yearly loss of three million dollars to the jitney while Public Service of New Jersey reported a four million dollar yearly loss.[3] The so-called "trolley lobby" managed effectively to kill the jitney in most American cities by 1918 by obtaining restrictive injunctions and prohibitive legislation. Unfortunately, one of the obstacles to reviving the jitney today is that the full extent and validity of these laws is not known. The few remaining legal jitney operations that managed to survive until today provide a distinctive reminder of the jitneys' past popularity, and these will be discussed subsequently.

Taxicabs, generally considered off-peak hour luxury vehicles, had been inadvertently left out of the restrictive legislation aimed at jitneys. Some 12 years later, during the depression, taxis began to operate along major arterial streets, competing with existing bus and trolley operations, using the same operational pattern the jitney had used earlier. The rash of "gypsy" or cut-rate taxis was a result of the increasingly high unemployment rate and the decreasing cost of owning an automobile. Simply, anyone who owned a car and had no job entered the taxi market as a gypsy taxi driver. As one disgruntled transit operator put it,

The whole system depends upon a surplus of unemployed, many of whom can be induced to work for practically nothing in order to maintain a modicum of self-respect.[4]

As with the jitney, the gypsy taxi posed terrible and costly competition to both transit operators and legitimate taxi companies; in 1930 the Washington, D.C., Street Car Company reported a revenue loss of $1,700,000 to taxi competition.[5] In 1931, the 84,000 legitimate American taxis carried 378,000,000 passengers grossing $252,000,000, while an estimated 66,000 gypsy cabs carried approximately the same number of passengers and grossed about the same revenue.[6] In 1930 New York City's 20,000 gypsy and legal taxis carried 10% of all public passengers with a revenue equal to 90% of the combined revenue of all other public modes.[7] Across the country, gypsy taxis reduced electric railway and bus revenues by an estimated 20%.[8] The competition between individual drivers themselves was often physical and bloody; in New York City several men were actually killed. Once again the threatened transit and taxi operations sought help from state and local legislatures and were successful in eliminating the legal gypsy taxicab in most American cities. Unfortunately, the same kind of political opposition to taxi expansion is in existence today on the part of monopolized taxi operators and some transit companies. Today only three American cities with populations over 100,000 allow taxis to operate like jitneys, but every major American city is known to host scores of illegal gypsy taxis.

With little doubt, the success of both the original jitney and its close cousin the gypsy taxi was a result of two key factors. One was simply the willingness of men to work long and hard hours for themselves to supply this service. When the remaining jitney systems and the nonmonopolized taxi markets are examined, as well as some illegal forms of both services that operate today, a similar pattern is found. While the transit and taxi industries suffer shortages of drivers, there are men willing to work long hours for low wages if they can be private entrepreneurs while providing this transit service. The second factor in the success of the original jitney and the gypsy taxi was that there was, in fact, a demand for such services. The examination of current taxi/jitney operations in light of this historical perspective reveals that this demand for flexible transportation service still exists in several areas of the modern urban community. A great deal of this demand is simply not being met or is being met illegally. Just as importantly, this same examination indicates that a far higher level of service would be provided if the artificial barriers imposed on taxis and jitneys were lifted.

CURRENT OPERATIONS—THE JITNEY

Probably the most interesting American jitney service still operating today is the one in Atlantic City, New Jersey. This service began in 1915 during a trolley car strike when ordinary private automobiles were pressed into service as jitneys. They charged the same fare as the trolleys (5 cents) and ran along the same main artery, Atlantic Avenue. Although the service was irregular and often unsatisfactory, the competition generated by the jitneys caused the trolley company to go into receivership in 1916 when the strike ended. As a result, several local ordinances were passed regulating the licensing of jitneys and making it unlawful for a jitney to operate on Atlantic Avenue. The Jitneymen moved to Pacific Avenue, a thoroughfare two blocks west and parallel to Atlantic Avenue, which they are using to this day. Ironically, Pacific Avenue is the most popular and desirable route for the largest number of riders because it accommodates business, hotels, restaurants, etc., on both sides of the Boardwalk. Today 190 individually owned jitneys belong to the Jitneymen's Association, which provides schedules and fleet-cost gas, tires, and maintenance. These 190 jitneymen are all required to possess mercantile licenses issued by the city. Although all jitneys are individually owned and operated, the Association is responsible for scheduling all jitneys on a 24-hour basis and for meeting demands created by major conventions and special events. Even in the hours from 2:00 to 5:30 AM, at least six jitneys are always on duty. Jitneymen work from eight to 12 hours a day, depending on their schedules, six day a week.[9] Since all drivers keep their own receipts, information on their income is limited. Reliable estimates are that drivers gross about $175.00 a week.

A private service, admittedly patterned after the Atlantic City jitney, was started in 1965 in Anaheim, California. Six routes are operated through the commercial and hotel/restaurant areas of Anaheim, also serving Disneyland, Knotts Berry Farm, and the baseball stadium. The small buses pick passengers up only at prescribed stops on the route but drop passengers off at any point. The busses are scheduled to operate on a zone-rate passenger fare and present an interesting cross between the conventional bus and the jitney.

Jitney service began in San Francisco during the 1915 Exposition and was later used during a 1916 streetcar strike. Today there are 117 jitneys, all individually owned or leased vehicles, which belong to one of two jitney associations. Operators originally used Cadillac limousines, but now use a mixture of Dodge, Chevrolet, and International vans. Although there are no schedules, jitneys are run on a four-minute headway during rush hours, 10-minute headways off-peak hours, along one of two routes—Mission Street or Third Street. Most of the 10-mile Mission Street route passes through the city's major business and commercial areas, while the four-mile Third Street route extends from Civic Center to Hunter's Point, a black ghetto. Drivers line up at either end of the route when they reach the end point and are "started" or staggered on the return trip according to the appropriate headway by employees of either of the two jitney associations.[10] Again no reliable information on the income of these drivers is available.

Some other modern jitney operations merit comment. In Baton Rouge, Louisiana, a number of blacks operate a jitney service from the black suburb of Scotlandville to downtown Baton Rouge, using old school buses. Within the city limits of Baton Rouge they run a closed door operation.[11] In the City of Miami, an all-black jitney service has been licensed and operating for over 40 years, carrying black workers from Liberty City, a Miami suburb, to downtown Miami via three prescribed routes. Although the routes of the jitneys are fixed, the schedules are not, but they generally operate between 5:00 and 9:00 AM and between 3:00 and 7:00 PM. Drivers, fares, and routes are under the supervision of the City of Miami, but most operational decisions are made by the owner-drivers themselves.[12]

This same type of pattern has been observed in several northern cities, but the northern operations are all illegal. An illegal jitney service has been operating for many years in Chicago in the black ghetto, although officially denied.[13] The New York Mayor's taxi commission estimated that the number of legal liveries operating illegally as jitneys or taxis in both black ghettos and downtown commercial districts might be over a thousand.[14] (These "liveries" are distinguished from the gypsy taxis to be discussed later because they are licensed only to perform a specific limousine-type service.)

An interesting operation, no longer in existence, was the St. Louis "Service Car" system. This system, which began in 1916 or 1917 during the American jitney craze, was in continuous operation for close to 50 years in St. Louis's black ghettos. All vehicles were individually owned, but all operation permits were in the hands of two companies and jitney owners paid for the privilege of operating under the permits. Some 85 vehicles of various makes ran along a roughly circular route from ghetto areas through the St. Louis commercial district and back to the ghetto. Service was unscheduled and often irregular. The jitneys often ran in direct competition with city transit lines, and a 1959 report on St. Louis's transportation system recommended that jitneys be eliminated because of their serious drain on transit revenues. A concerted political effort by ghetto residents and jitney owners apparently kept the system alive until 1965, when the operating permits of both jitney companies were purchased by the Bi-State Transit Authority. Individual jitney owners were not reimbursed for the losses.[15] Once again, jitney service was legislated out of business.

All of these systems were discovered by the author in discussions with people who had been involved in the transit industry for many years. Published research on American jitney systems is almost nonexistent. More than likely there are other such systems operating in America, both legally and illegally, of which the author has not been made aware. Another paper given at the American Society of Mechanical Engineers Transportation Conference has documented the growth of similar operations in middle-class suburban communities.[16] It seems that when a community develops a particular transportation need and this need is not met by traditional transit facilities operations like the jitney spring up to meet the need. Just as importantly, it appears that there are a large number of individual private entrepreneurs willing to provide this "unconventional" service.

The common denominator of all these jitney systems is that most riders are either downtown businessmen, shoppers, tourists, or ghetto residents. This seems to indicate that certain specific types of services are being demanded by the same kinds of people throughout the country. Two other examples may also illustrate this common group of transit needs unmet by conventional services: new downtown circulation systems and the modern jitney systems operating in foreign nations. Current patterns of taxicab usage, to be discussed, also show these similar needs for service.

MINIBUSES

In addition to the few jitney operations, a further indication of the demand by businessmen, shoppers, and tourists for a flexible downtown circulation system is the success of several downtown circulation system programs utilizing small buses operating on a jitney principle, i.e., along a fixed route on a flat rate per passenger basis. The most famous such system was inaugurated in Washington, D.C. In 1964 the District of Columbia implemented a low cost flexible transportation system in the downtown business area of Washington, a system very similar to the current jitney operations in Latin American cities, to be discussed. The Mini-buses,** as they were called, ran through retail core areas along a fixed route with frequent headways for a flat 5 cent fare. The demonstration project was deemed an overwhelming success and the service was taken over by the Washington Metropolitan Transit Commission.[17] The Commission has operated the Mini-buses continuously since the November 1964 termination of the demonstration project and has added two additional routes serving various government agencies and the course from the new Southwest development to Capitol Hill.[18] The Commission has upped the flat-rate fare to 15 cents and is currently running 14 buses in all, eight in the downtown area, on three-minute headways before 3:00 PM and on six-minute headways after 3:00 PM. (The cutback was due to lack of drivers, not patrons!) [19]

The success of the Washington, D.C., operation has spurred other cities, as well as core area merchants, to invest in such central business district circulation systems. The City of Detroit invested in two small bus routes in the downtown area in January 1969. One route, carrying 2000 passengers daily at a 10 cent fare, runs at three to five minute headways and is currently breaking even financially. The second "Miniloop" is not yet breaking even, but some route changes have been proposed to meet this problem. Above all, the manager of the operation reports that the City is still enthusiastic about the service.[20]

Several other cities are considering small bus circulation systems in their central business districts. The Southern California Rapid Transit District, serving Los Angeles, began operating a fleet of small buses to serve the Civic Center and the central business district in 1971. The 10 cent fixed-fare buses run on three-minute headways on fixed routes between 9:00 AM and 4:00 PM, Monday through Saturday.[21] Battelle Memorial Institute, in a 1968 study for the City of Columbus, recommended that the City institute an elevated "mini-train" system in the downtown core area, supplemented by small buses running on fixed routes with frequent headways.[22]

A number of downtown retailers are also willing to pay any costs of such a system, without governmental aid or subsidy, because they believe the service brings them increased profits. In Lincoln, Nebraska, 95 downtown firms are currently underwriting the Lincoln "Mini-Line" at a cost of $55,000. The four Mini-Line service buses carry approximately 850 passengers a day at a 10 cent fare and are far from breaking even, but apparently the businessmen involved feel it is serving their own needs.[23] As with jitney operations, it is entirely possible that the author has not been made aware of all systems of this type that are currently in operation; there are doubtless many more.

A brief look at modern jitney systems operating in large, foreign metropolitan areas gives an idea of the extent to which these systems can develop in an unrestricted market. In foreign nations, jitneys are viable and important parts of the urban transportation system. In Caracas and Buenos Aires, large jitneys (colectivos) carry more than half of the cities' daily travelers.[24, 25] An experienced observer reports that Santiago, Chile, and Lima, Peru, which maintain smaller, more traditional jitneys, provide even better and more organized service than Buenos Aires.[26] Manila, Philippines, responding to a 1963 questionnaire sent by the City of Houston, reported that "jeepneys" and taxis accounted for 25% of the city's mass transit vehicles.[27] Seoul, Korea, reported that jitneys or micro-buses carried 15% of all daily passengers.[28] Teheran, Iran, reported that jitneys and taxis constituted its entire mass transit system.[29]

CURRENT OPERATIONS—THE TAXICAB

Taxicab operations were originally a free enterprise service, but today such operations in all American cities over 100,000, except three, are rigid monopolies or franchises. Some cities, such as New York, Chicago, and Boston, restrict the actual number of taxis that may operate within the city, while other cities limit the number of companies permitted to provide taxi service. Not surprisingly, the three cities not numerically limiting taxi service—Washington, D.C., Atlanta, and Honolulu—have far higher numbers of taxis per capita than the restricted cities.

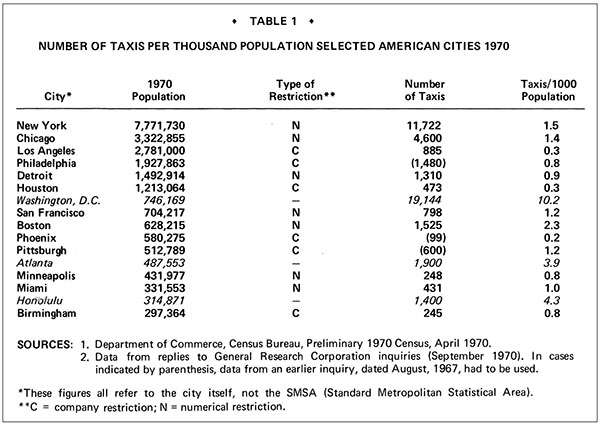

Table 1 illustrates the large disparities between the taxis per capita in restricted and unrestricted cities. Certainly taxis-per-capita is a simplistic measure of the type of taxi service available in any given city, but the author's attempts to explain the larger number of taxis in the unregulated cities by the use of 11 different measures of economic and tourist activity has been unsuccessful.[30] The overriding factor in all cases is the lack of restriction on entry into the taxicab market. Of the 13 restricted cities in Table 1, seven restrict the actual number of taxis, while six restrict only the number of companies, which in turn may operate as many taxis as they choose. The most important conclusion presented by the data in Table 1 is that it is not mere numerical restriction which inhibits the growth of the taxi industry in any city, for the franchised companies could generally add as many taxis as they pleased. The most significant inhibition on taxi supply is the restriction in both types of regulated cities on the entry of individual owner-drivers.

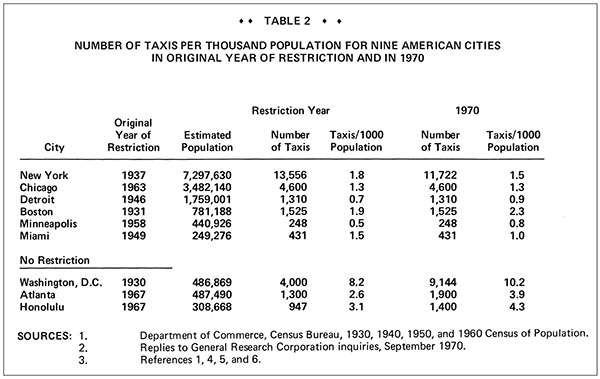

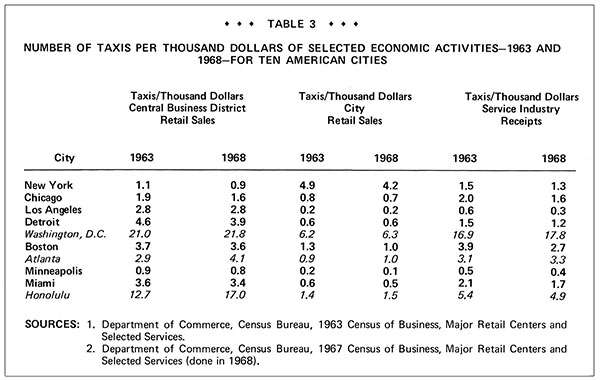

Table 2 gives a historical perspective of the relationship between the number of taxis per capita in the original year of restriction (where applicable) and in 1970 for both regulated and unregulated cities (for those cities in Table 2 where historical data is available). Because central city populations in most metropolitans SMSA's have been decreasing since World War II, the taxi-per-capita ratios for the regulated cities have tended to increase slightly although the number of taxis may have stayed constant for years (40 years in Boston!). There does not seem to be a definite trend over time among the regulated cities, but the three unregulated cities (two of which have experienced population increases rather than decreases) have all shown definite and significant increase over time in taxis per capita. Table 2 indicates that taxi-per-population ratios may be unreliable for historical comparisons among cities, since they reflect the post-war population's "move to the suburbs" as an overall increase in available taxis (in the regulated cities). Actually, many suburban residents still work, shop, transact business, or play in the large cities and still make demands on that city's taxi supply. Table 3 presents taxi ratios based on three key indicators of business and commercial activity within the city. Unfortunately, these indexes suffer from a different kind of incomparability; because of conditions unique to any city, a certain economic measurement may be very low, giving an artificially high taxi-to-index ratio, e.g., Los Angeles' small central business district retail sales. Thus comparisons between each city's indexes are generally unreliable, although large differences may be significant. However, historical comparisons within each city itself should be reliable; Table 3 presents the taxi ratios for three economic variables in 1963 and 1968 for all Table 1 cities where historical data is available.

The picture that emerges from Table 3 is clear; in every restricted city the taxi-per-index ratio has decreased, even if only slightly in just a five-year period (this decrease is not always clear from the rounded-off figures). In every unrestricted city, every taxi-to-index ratio went up (except Honolulu's service industry sales) in the same five-year period. Clearly the number of taxis is increasing in some relationship to the increase in economic activity in the unrestricted cities. It seems clear that increased economic activity caused an increase in demand for taxi service. The unrestricted cities have been able to fulfill this increased demand for taxi service while the restricted cities have been prevented from doing so.

The sketchy data*** available on taxi users both validates the type of economic index used in Table 3 and gives us an idea where the additional unfulfilled demand in restricted cities comes from.

Leaving aside "home" trips, two distinct types of taxi trips emerge. One group of taxi users are "housewives, students, unemployed, retired, or incapacitated persons" traveling for social, shopping, or recreational functions or work-related activities but not to work.[31] The other group of taxi users are professionals going to work, to eat, or on work-related activities, most often in the central business district. The first group are generally non-drivers; the second group are generally drivers who do not care to drive.

The first group fits well with the traditional view of the "typical" taxi rider, but it should be made clear that a rider need not be well-off to fit the characteristics of this group. Although the taxi has always been considered a luxury vehicle, the poor actually use the taxi for a disproportionate number of trips. A study in Boston found that the poor used the taxi for 5% of all trips and then, when car ownership was controlled, those with an income of under $4,000 used the taxi as a travel mode as often as those with incomes over $10,000.[32] Another Boston study found that those with incomes under $4,000 contributed 20% of all taxi income.[33]

All indications are that the number of taxis allowed in restricted cities is far from the number demanded. Most large cities would use far more taxi service if it were available. In restricted cities, taxis tend to serve only the more profitable downtown business district (the "professional" group of taxi users), leaving the inner city (the poor) and the suburb (housewives and students) poorly served.

Black inner city residents in many cities, and underserved businessmen in New York City as well, have partially overcome the lack of necessary taxi service through a variety of illegal means. Taxis in New York allow group riding, although the practice is illegal in New York as in most American cities. In addition, the NEW YORK TIMES has estimated that there are between 4,000 and 5,000 illegal gypsy taxis operating in New York City and its ghettos.[34] In Bedford-Stuyvesant, Pittsburgh's Hill district, and Cleveland's Hough, illegal gypsy taxis cruise the streets openly.

In the past, if the gypsy taxis stayed within the inner city they were left alone by the police and the legal taxi operators, a strong indication that the legal taxis did not really care to serve the inner city. When the gypsy cabs began to invade middle-class areas, the legitimate monopolies became worried. The New York Metropolitan Taxicab Board of Trade took a full-page ad in the NEW YORK TIMES on 13 January 1969 to warn customers of the menace they face using unlicensed cabs:

Ignore them [the signs of an unlicensed cab] and you may be putting yourself in the care of a murderer, a thief, or even a rapist. The gypsy driver, by the very fact he solicits on the street, is at least a crook, but he may have big ideas which include you.[35]

Unfortunately, there is more danger involved in using a gypsy taxi, but the poor in restricted cities are often forced to make the decision between using a potentially dangerous travel mode or none at all.

On the other extreme, Washington, D.C., is the most striking example of the type of taxi service available in a legal nonrestricted taxi market. Although the number of taxis fluctuates slightly in Washington, in 1970 there were the same number of taxis in Washington as there were in New York City, although New York is almost 10 times larger. Fares in Washington are on a zone basis and group riding is allowed, making the taxi a convenient and often inexpensive travel mode for Washington ghetto residents. A significant feature of the Washington system is really the number of semiautonomous and autonomous operators who run their business as they see fit during the hours they feel like working, and who are clearly filling a demand for the type of service they offer. The economics of the free market seem to prevail—when a saturation point is reached, the less profitable operators drop out of the market.

As with jitney riders, there appears to be a common group of taxi riders. Here the evidence is even clearer that the group demanding this transportation service is larger than the group actually being provided the service. But in addition to a demand for more of the traditional service, there is clearly a demand for a different kind of service: group riding in taxis, a service which approaches the jitney. And most importantly, it is clear that there are men willing to provide both types of service, legally and illegally, if they can work for themselves.

CONCLUSIONS

The foregoing analyses seem to tell the same story over and over again. This paper has demonstrated very clearly that for over 50 years and through two world wars there has been a series of transportation needs that are not met by fixed-route or fixed-rail large vehicle systems. (The growth of the automobile has demonstrated the same thing.) These needs have always had pretty much the same character, even in widely different social and economic communities, dealing with shopping and commercial activities, business, and tourism. For over 50 years there have been people with enough initiative to be willing to provide service to fill these transportation demands and enough knowledge or common sense to know where the demand actually is. And just like clockwork, this analysis shows that fixed-route operators, themselves unwilling or unable to provide the demanded service, have managed to protect their interests against competition by restricting the flexible-route service out of business; the story of the 1918 defeat of the Los Angeles jitney reads the same as the 1965 defeat of the St. Louis service car. And once again, in every instance there seem to be people with more initiative—or perhaps just disregard for the law—who are willing to defy these restrictions to provide what gives every indication of being profitable and obviously demanded transportation service.

Perhaps the only new factor in the saga is the recent intrusion of the government in a positive way rather than in a purely regulatory fashion. But even the types of programs formulated by the government to solve these problems are not terribly new; in 1918, trolley operators tried several ways to beat the jitney in the free market. Some tried to offer jitney-type service but found they could not keep fares competitive because of their overhead, and this was in the days before strong unions and high labor costs![36] They offered to hire the jitney owner/operators but found jitney operators refused to work the same kind of hours for the same wages if employed by a trolley company.[37] The only strategy that seemed to have any effect was to simply increase transit service.[38]

The message is clear; people of differing economic backgrounds provide the demand for an inexpensive and flexible type of transit service met best by small, frequently scheduled, flexibly routed vehicles. Others, namely operators of jitney-type vehicles, are willing to provide this service because they like working for themselves. Some of these owner/operators will provide the service even if it is illegal; more people would do so if it were not illegal. Demand would probably increase if the service were both legal and available because people would quickly adapt their needs to the new system.

PROBLEMS WITH THE SOLUTION

One approach to the problem presented in this paper is to admit the obvious fact that people of all economic means are seemingly able to get around unfair or silly restrictions and obtain transportation without the aid of the government. Political controversy would be avoided by simply letting the situation continue as it is. Unfortunately, to allow people to continue an illegal activity so that a city can have an adequate transportation system is basically unwise. More importantly, those drivers who are already breaking a law may find it easy to break other laws. The poor, who seem to be the greatest users of illegal taxis and jitneys, are generally the greatest victims of crimes anyway. Lastly, illegal operations that continue under a laissez-faire attitude of benevolent authorities have a very uncertain future; a 1969 study of the Hill District Model City Neighborhood in Pittsburgh recommended that illegal gypsy cabs be abolished immediately as a means of providing better "transportation coordination" in the area.[39]

The solution proposed by the author of this paper is to encourage the free-operation of taxis and jitneys in most metropolitan areas. Admittedly this proposed course presents many problems. Even if we establish basic insurance, safety, and licensing requirements to protect the public, and make sure that effective mechanisms are available to enforce these regulations, other difficulties arise. None of these difficulties is new, although answers have not been forthcoming.

Probably one of the most valid criticisms leveled against the jitney and the taxi in their early history was that they caused increased downtown congestion. In April 1930, a Public Utilities magazine claimed that 70% of all traffic at a major New York City downtown intersection (42nd and Broadway) was taxis and 60% of them were empty. [40] In London in 1966 when taxis in the West End went on a one day strike, the Ministry of Transport took the opportunity to measure traffic flows in the area; they found that all journey speeds in the area increased markedly in the absence of taxis: 78% in the morning, and 44% in the afternoon.[41] Preliminary surveys taken during the recent New York City taxi strike have shown a similar decrease in traffic congestion in the absence of taxis. This congestion is a difficult problem to solve because congestion caused by many stops, and slow cruising is inherent in taxi operations. However, jitney operations tend to reduce downtown congestion; the Washington Metropolitan Commission found that the Mini-bus reduced congestion 4% in downtown Washington. Perhaps the total congestion that arises can be viewed as an alternative to increasing the number of land-consuming parking structures, since an ample supply of taxis and jitneys may decrease the need for taking cars downtown.

In addition, another early criticism of taxis and jitneys was that they had high accident rates. In 1915, the National Municipal League claimed that Portland had experienced a 400% increase in accidents in the downtown area due to the introduction of the jitney, while Los Angeles had suffered a 22% increase in accidents.[42] Another magazine claimed that 20% of all New York City's traffic accidents in 1931 were caused by taxis, although taxis represented only 2% of the State's registered cars.[43] While this may always be a serious difficulty, some of the accident problems would probably be eliminated by more stringent licensing and safety regulations and the resulting police enforcement of these regulations.

Another important and obviously true criticism of the taxi and the jitney is that they offer severe and often deadly competition to existing transit operators. In the second decade of this century when trolley operators, like their earlier railroad counterparts, were affluent, this seemed a far less important problem than it does now. Today most large city transit operations are publicly owned and generally heavily subsidized; they provide needed transportation services to many people, including inner city residents, who could not travel otherwise. Clearly many routes within a city are so heavily traveled that it is efficient and profitable to run a fixed route scheduled service. But most transit companies are running unprofitable lines as well, using the profitable lines to "cross-subsidize" the losing ones. This fairly common use of cross-subsidization suggests two solutions.

First, since many of the losing bus routes are in the inner city or in the suburbs (and often continued for that very reason), it is possible that use of expanded jitney and the taxis service would make these routes unnecessary. This leads to the second solution. If transit operators were no longer required to cross-subsidize losing lines, they would not need to make the same kind of profit on heavily traveled routes. The point at which the operation no longer requires governmental subsidy is the point where the taxi and jitney can be allowed to offer competitive service to the public. Some individual routes still may have to be totally protected from taxi/jitney competition or the competition might have to be restricted by time of day. (Most transit operators would welcome peak-hour competition if their rolling stock and labor could be based on their off-peak hour usage.) Restrictions to protect a certain group of riders may be contrasted with the normal procedure of protecting the transit operators who serve these riders. Such restrictions would seem relatively minor to metropolitan travelers as compared to services they lose now because of current restrictions on taxis and jitneys.

At the same time, taxi and jitney operations are clearly adaptable to the use of modern sophisticated techniques, particularly computer dispatch on demand. While the success of a demand-scheduled bus system may depend on the routing and scheduling ability of its computer algorithms, success will mainly depend on the level and kind of service demanded. From the data and analysis presented in this paper, the necessary demand for this kind of service would seem to exist in most metropolitan areas. A crucial consideration for policymakers is that current taxi and jitney operations can evolve into sophisticated transportation networks in the future.

PROSPECTUS

One of the most interesting aspects of a deregulated taxicab system or of a full-fledged jitney operation is the opportunity it opens for both consumers (i.e., passengers) and producers (i.e., drivers). Deregulation of taxi and jitney markets will increase the number of available vehicles and thus increase the quantity of this service available to both downtown travelers and ghetto residents. This appears to be an immediate and effective answer to some inner city transportation problems as well as to central business district circulation problems. In addition, the new transportation scheme might be an effective solution to some inner city employment problems; an inner city resident who would not now consider working for someone else as a taxi driver might well consider being his own boss as a taxi or jitney driver. In the early 1930s when the first monopolizing of taxicab systems began, a "concerned citizen" warned:

[The taxicab business] has long been considered a logical haven into which the unemployed may drift…one of the chief requisites of licensees is that they be without visible means of support and have large families.[44]

This inversion of desired means over desired ends is almost amusing. Nevertheless employing the unemployed (with or without large families) as self-employed entrepreneurs in a free enterprise taxi or jitney market does seem to be an effective solution to one of the problems of today's urban transportation.

No one claims that deregulation of the taxi and the jitney industry is easy or could be accomplished without great political cost. Mayor Lindsay of New York has been trying for eight years to reissue the less than 2,000 taxi medallions surrendered since the 1937 taxi limit was fixed. Pressure from the taxi industry has been strong enough to prevent him from doing so.[45]

No one can claim that there is a totally right or totally wrong side to this question. In many restricted cities, taxi operators had to buy medallions at prices ranging from $20,000 to $30,000; if free entry were permitted these medallions would become worthless. In any city where the jitney or the taxi offered severe competition to transit operations, bus drivers might lose their jobs. But the question to be answered is whether the rights of citizens of a metropolitan area are to be neglected in favor of "driver" rights. The mixed-up, half-legal, half-illegal transportation system operating in many metropolitan communities cannot be allowed to continue in spite of the costs that will be involved in changing it.

Ms. Rosenbloom is currently a doctoral student at UCLA in Political Science. She has been a Graduate Fellow of the Institute of Transportation and Traffic Engineering since 1969 and has been involved in the analysis of urban transportation systems since 1967, when she took part in the HUD-sponsored Future Urban Transportation Study. As a consultant to General Research Corporation, she has continued her research into urban transportation systems with emphasis on inner city transportation modes. She served for 2-1/2 years as a consultant to the State of California Transportation-Employment Project in Watts. An earlier summary of her taxi and jitney research was published in TRANS-ACTION and will be included in ECONOMICS: A SYNERGETIC APPROACH to be published this year by the Dryden Press. Copyright 1971 by General Research Corp.

*Headway is the time interval between two vehicles traveling in the same direction on the same route.

**Mini-bus has become a copyrighted trade name of the company that originally manufactured the Washington, D.C., buses. These buses were not so named in 1964, however; it is believed that the term was coined by a WASHINGTON POST reporter. Unfortunately, the term "mini-bus" has come into popular usage and is often used carelessly to refer to small buses or buses providing jitney-type service.

***The only three major studies which compiled separate ridership figures and ridership characteristics for taxicabs are the 1956 Chicago Area Transit Study, the 1963 Pittsburgh Area Study, and the 1969 Tri-State Regional Profile. This last study gives data for New York City, which may be unreliable; it is estimated that there are 5000 gypsy taxis in New York, one-half as many as there are legal taxis. Therefore, the "legal" data gives an incomplete picture at best.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

[1] J.C. Thirlwall, "The Jitney Problem," GENERAL ELECTRIC REVIEW, July 1915, Vol. 18, No. 7.

[2] R. Farmer, "Whatever Happened to the Jitney?" TRAFFIC QUARTERLY, July 1965.

[3] J.A. Miller, FARES PLEASE; FROM HORSECARS TO STREAMLINERS (New York: D. Appleton-Century, 1941).

[4] H.S. Simpson, "Taxicab Regulation: A Review of its Present Status, Based upon a Nationwide Survey," AMERICAN CITY, August 1932.

[5] F.X. Welch, "The Inevitable Regulation of the Taxi," PUBLIC UTILITIES FORTNIGHTLY, Vol. 5, 26 June 1930.

[6] R. Tomkin, "The Taxi Runs Amuck," AMERICAN MERCURY, Vol. 26, No. 104, August 1932, p. 385.

[7] Simpson, op. cit.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Simpson and Curtin, ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF JITNEYS IN ATLANTIC CITY, NEW JERSEY, Undated mimeographed memorandum, Philadelphia.

[10] Stanford Research Institute, unpublished memorandum, September 1970.

[11] Letter from J.V. Jack, Supervisor, Motor Transportation Division, Louisiana Public Service Commission, 20 April 1970.

[12] Letter from Sgt. M.M. Ogle, Taxicab Division, City of Miami, 28 April 1970.

[13] Letter from Chicago Transit Authority, 11 June 1970.

[14] RECOMMENDATIONS TO J.V. LINDSAY, MAYOR OF NEW YORK, Mayor's Taxi Study Panel, December 1966.

[15] Letter from St. Louis City Attorney's Office, 15 June 1970.

[16] R.J. Solomon, and A. Saltzman, A HISTORY OF US MASS TRANSPORTATION DEVELOPMENT AND INNOVATION, M.I.T. Urban Systems Laboratory, October 1970.

[17] THE MINIBUS IN WASHINGTON, D.C., Mass Transportation Demonstration Project, 1965.

[18] Letter from Melvin E. Lewis, Executive Director, Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Commission, 7 July 1969.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Letter from O. Jack Chesterfield, Manager of Marketing and Schedule Planning, Department of Street Railways, City of Detroit, 18 July 1969.

[21] LOS ANGELES TIMES, 21 April 1970.

[22] Battelle Memorial Institute, TRANSIT IN COLUMBUS; A SUMMARY REPORT TO THE ADVISORY COMMISSION ON TRANSIT, 16 April 1968.

[23] Letter from Robert O. Stuewig, Director, Lincoln Center Service Co., 21 April 1970.

[24] S. Rosenbloom, TAXIS, JITNEYS AND POVERTY, General Research Corporation IMR-860, June 1968, p. 7.

[25] W. Kudlick, "Carros Por Puesto—The 'Jitney' Taxi System of Caracas, Venezuela," HIGHWAY RESEARCH RECORD, No. 283, 1969.

[26] Letter from Dr. Wesley E. Bjur, Director, International Public Administration Center, University of Southern California, 16 February 1970.

[27] City of Houston, Director of Public Service, WORLD-WIDE TRANSIT STUDY, Houston, Texas, 15 November 1963.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] S. Rosenbloom, CHARACTERISTICS OF TAXI SUPPLY AND DEMAND IN SELECTED METROPOLITAN AREAS, General Research Corporation IMR-697/1, August 1967, p. 11.

[31] E.E. Harris, A REPORT ON AREA TAXIS, Pittsburgh Area Transportation Study, 1963.

[32] M.A. Coogan, SOCIAL CLASS AS A RELEVANT FACTOR IN THE USAGE OF PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION, unpublished master's thesis, March 1969.

[33] P.B. Herr, and A. Fleischer, THE MOBILITY OF THE POOR, Joint Center for Urban Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University, 7 June 1968.

[34] NEW YORK TIMES editorial, "The Taxicab Mess," 27 July 1969.

[35] NEW YORK TIMES, 13 January 1969, Sec. C, p. 21.

[36] Thirwell, op. cit., p. 605.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid., p. 606.

[39] A.D. Little, Report to Pittsburgh Model Cities Program.

[40] Welch, op. cit., p. 832.

[41] M. Marlowe, EFFECT OF ONE DAY'S WITHDRAWAL OF TAXI SERVICES ON TRAFFIC IN THE WEST END OF LONDON, Great Britain Road Research Laboratory, Report 114, Ministry of Transport.

[42] NATIONAL MUNICIPAL REVIEW, October 1915.

[43] Tompkin, op. cit., p. 387.

[44] Hawley, op. cit., p. 72.

[45] NEW YORK TIMES editorial, op. cit.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Taxis and Jitneys."

Show Comments (0)