Adopted 4-Year-Old Daughter of Americans Probably Won't Be Deported. Either Way, Our Immigration System Is Broken.

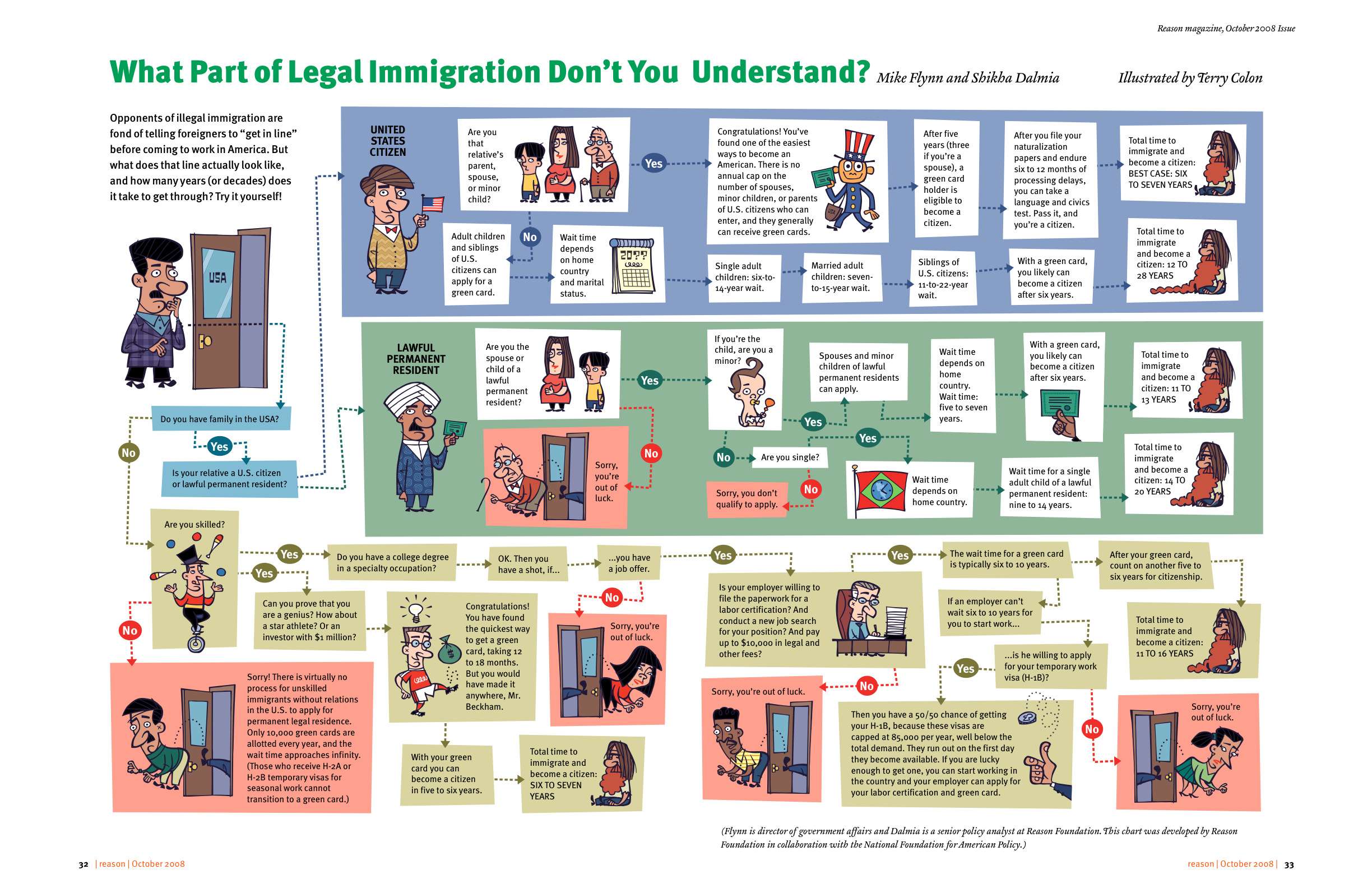

Angela Becerra's case is a reminder that legal immigration is more complicated than just "getting in line."

Both of her parents are legal U.S. citizens. But if 4-year-old Angela Becerra doesn't leave the country within the next three weeks, she runs the risk of deportation.

When Angela was born in May 2014, Amy and Marco Becerra were living in Peru. Marco is a dual U.S.–Peruvian citizen, and the couple owned home in the country. Though they're not Angela's biological parents, they've been taking care of the little girl for her entire life.

Angela was less than two weeks old when she was left at an orphanage by her developmentally disabled mother. Amy and her husband took Angela in and eventually decided to adopt her. Since they were living in Peru, the adoption was finalized in a Peruvian court last April. "The unique thing about Angela's adoption is it's not an international adoption. It's a domestic adoption in Peru," Amy tells KDVR.

Around that time, the family decided to move to Colorado. They had to send in an immigration application for Angela, but her case kept getting delayed.

Eventually, Angela came to the U.S. on tourist visa. But that visa expires at the end of the month, and her immigration application has been denied. "If she expires her visa, she is officially here as an undocumented alien, and legally is at risk for deportation even though both her parents are citizens," Amy tells KDVR.

The Becerras say they don't know why Angela's immigration application was denied. David Bier, an immigration policy analyst at the Cato Institute, suspects it has to do with their application for a tourist visa. "You are just not supposed to use a tourist visa to come to the United States to then apply for permanent residency," Bier tells Reason. Bier says it sounds like the Becerras first applied for a permanent visa, then opted for a tourist one instead. "As a consequence of that, the administration treats you as having given up your other visa," he adds.

Matt Kolken, an immigration attorney and national immigration reform advocate, thinks there's a viable solution. "The law specifically provides that if you are an immediate relative of a United States citizen, [you're] eligible to apply for adjustment of status, which is to become a green-card holder from inside of the country," says Kolken.

Since Angela is a child of two U.S. citizens and has already been "inspected" and "admitted" into the country, this shouldn't be a problem. "Just because she becomes an undocumented immigrant for a temporary period, if you're a minor and you're the child of U.S. citizens you should be able to get a green card and get this fixed," Bier says.

Still, "this is how people get entrapped in a broken system where things don't make sense." Angela's story will probably have a happy ending. But people who say legal immigrants can just "get in line" should keep stories like hers in mind.

Show Comments (120)