The Guantanamo Defense Lawyers Quit Because They Found Microphones in Their Office Walls

The USS Cole defense team came to believe their meetings with their client were being bugged.

The team of lawyers defending the accused USS Cole bomber resigned because they discovered their client meeting room was bugged, according to a report yesterday in The Miami Herald.

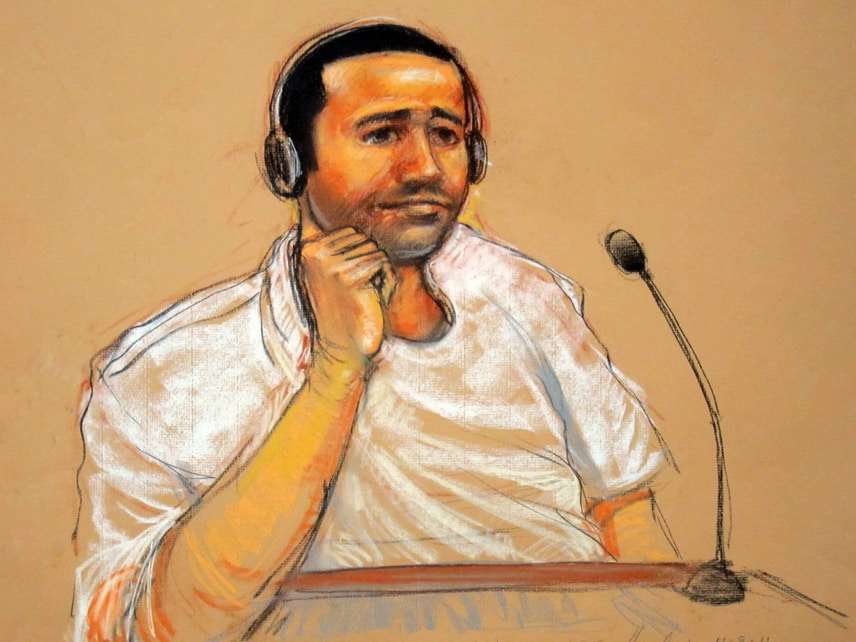

Attorneys for Abd al Rahim al Nashiri, the Saudi man charged with orchestrating the 2000 attack on the U.S. Navy destroyer, quit the case in protest back in October and have refused multiple orders from the presiding judge to return to the commission. Up to now, the exact motivation for their departure has been unclear, beyond that it was related to a dispute over attorney-client confidentiality.

But a prosecution filing obtained by Herald reporter Carol Rosenberg, the only journalist continuing to cover the trial's proceedings, gives a fuller account of the events that have sent the 17-year-old effort to try the case grinding to a halt.

Those events began last August, when the defense team discovered that there were a number of microphones built into the walls of the room designated for them to meet with al Nashiri, who is being held in Guantanamo's mysterious Camp 7 under undisclosed conditions of confinement.

The defense team asked to raise the issue of the microphones before the judge presiding over the military commission, Air Force Colonel Vance Spath. They also wanted to get discovery regarding whether anyone had listened in on their meetings. But Spath wouldn't even allow them to specify their complaint in open court, and he denied the discovery motions. The three civilian attorneys then resigned, arguing that Spath had made ethical representation impossible.

Those resignations set off a bitter feud between Spath and the defense team as he attempted to get them to return to the case. When the Marine general in charge of the defense team refused to order their attendance at the commission, Spath held him in contempt and sentenced him to home confinement before being overruled by officials at the Department of Defense.

Then, apparently in a moment of intense frustration, Spath instructed the military prosecutors to draw up arrest warrants for the recalcitrant attorneys—even as he observed that their arrest would probably impede the proceedings even further by jeopardizing their security clearances, and thus their ability to keep representing al Nashiri.

Spath later thought better of his order, declining to arrest the lawyers but suspending the proceedings entirely instead.

In a lengthy monologue that betrayed intense emotional distress, Spath said from the bench that the case had caused him to consider retiring from the military. The stress and uncertainty had made him unable to sleep, the judge said, and he had resorted to running on the treadmill all night. Without instructions from a higher court, he couldn't keep hearing the case.

"We're done until a superior court tells me to keep going," he said. "We are in abatement. We're out."

Prosecutors are now asking the U.S. Court of Military Commissions Review, the intermediate appellate court for court-martial proceedings, to order Spath to resume the case. They claim the microphones were left over from previous unrelated interrogations conducted in the room, and that they were never turned on during al Nashiri's meetings with the defense.

Show Comments (22)