What About the Debt? Trump's SOTU Ignores a $20 Trillion Time Bomb

If a Republican president can't address a Republican-controlled Congress without paying lip service to the idea of cutting spending, what good are Republicans?

The State of the Union address is traditionally an opportunity for presidents to make outlandish promises. It's where you talk about going to Mars and bringing peace to the Middle East.

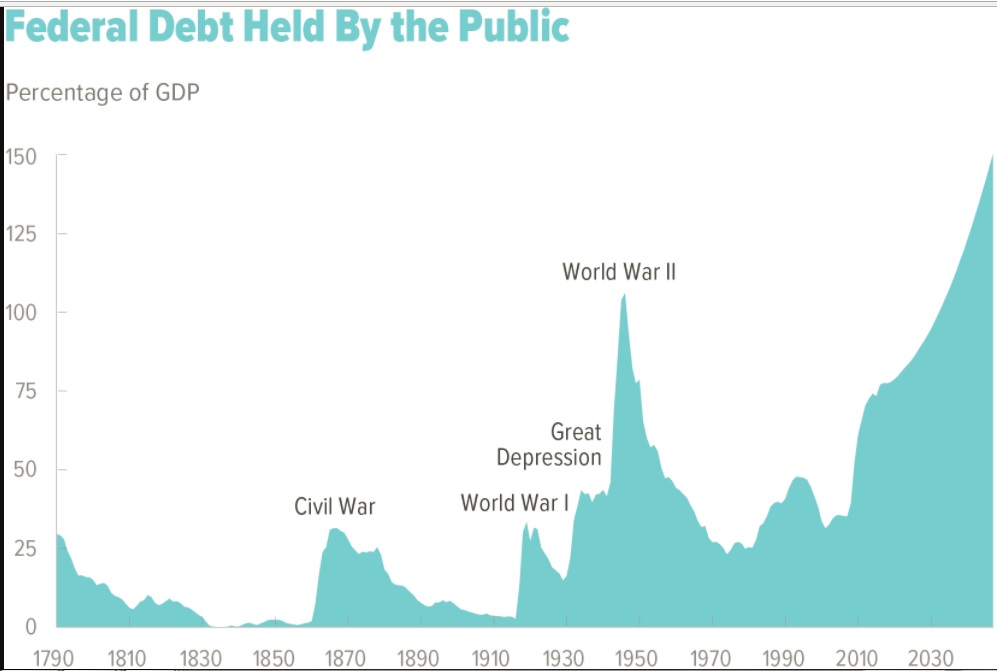

Historically, it has also been an opportunity to discuss the sorry state of America's entitlements and the unsustainable trajectory of the national debt. Like those plans for interplanetary travel and for spreading democracy at the point of a Tomahawk missile, these annual promises to address the country's debt are not meant to be taken completely seriously. Still, it's an important box to check—an indication that, yes, the president is aware of America's long-term fiscal crisis, and an acknowledgment that someone, someday, ought to do something about it.

President Donald Trump skipped that box in his first official State of the Union address. He did not once utter the words "debt" or "entitlement." The only mention of "deficit" came in reference to America's supposed "infrastructure deficit"—in other words, it came in a call for even more government spending. Trump did reference the "sequester," a colloquial name for the 2013 budget act instituting limited cuts in discretionary spending, but only long enough to call it "dangerous" and to ask for Congress to repeal it so more tax money can be shoveled into the Pentagon.

Trump had a lot to say about the tax reforms he signed into law in December. Rightly so. Cutting corporate and personal income taxes will let Americans keep more of their own money and will likely boost the economy in 2018 and beyond.

But the tax bill will also add an estimated $1.5 trillion to the national debt over the next 10 years. Republicans can pat themselves on the back for cutting taxes, but unless spending is reduced all they've really done is postpone the payment of taxes for 10 years or so.

In the short term, Congress has to pass a budget that isn't wildly out of whack. While the Congressional Budget Office says the deficit for the current fiscal year is only about $666 billion—only, as if a figure twice the size of Canada's annual budget is nothing—it's going to begin growing next year. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget projects that the country could face a trillion-dollar deficit in the next fiscal year, with annual deficits of $2 trillion expected by the mid-2020s. That's madness.

In the long term, the largest driver of the national debt are entitlement programs that run on autopilot, without needing to be renegotiated as part of each new congressional budget. In fiscal year 2016, $2.47 trillion of the federal government's $3.66 trillion in non-interest expenses—in other words, 67 percent of every dollar spent that wasn't going to payments on the national debt—went toward "mandatory spending" on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Within a decade, those three programs will consume $4.14 trillion annually, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Congress, meanwhile, can hardly scrape together the votes for a months-long continuing resolution. Even with full Republican control, passing an actual budget—a budget that would affect only that other 33 percent of federal spending—seems like an impossible dream. Tackling entitlement costs will be an even bigger fight.

Trump's refusal to acknowledge the debt last night was on-brand for him. During the campaign, he rarely talked about entitlements except to make promises about saving Social Security. He meant that he would protect the national pension program from cuts, but anyone serious about "saving" America's entitlement programs should recognize that insolvency is a bigger threat.

And that's true not only for entitlements, but for the entire economy.

"Large and growing federal debt over the coming decades would hurt the economy and constrain future budget policy," the Congressional Budget Office warned in March of last year. "The amount of debt that is projected…would reduce national saving and income in the long term; increase the government's interest costs, putting more pressure on the rest of the budget; limit lawmakers' ability to respond to unforeseen events; and increase the likelihood of a fiscal crisis."

So a Republican president, speaking before a Republican-controlled Congress, in a year when the national debt surpassed the symbolically important threshold of $20 trillion, failed to pay even lip service to the country's fiscal imbalance.

"Between 1997 and 2013, American presidents delivered 15 State of the Union addresses and two addresses by presidents-elect to joint sessions of Congress. All 17 speeches addressed the need for long-term entitlement reform." Ah, memories. https://t.co/WU51WKwiO5

— Matt Welch (@MattWelch) January 31, 2018

No, those pledges from previous POTUSes didn't do much to fix the problem. But if the president isn't willing to toss in entitlement reform or deficit reduction among the other pie-in-the-sky proposals in his State of the Union address, where do they rank on his list of priorities? Are they there at all?

Trump devoted about 500 words in his speech to the threat posed by North Korea. A far more threatening bomb continues to tick away right under his nose.

Show Comments (51)