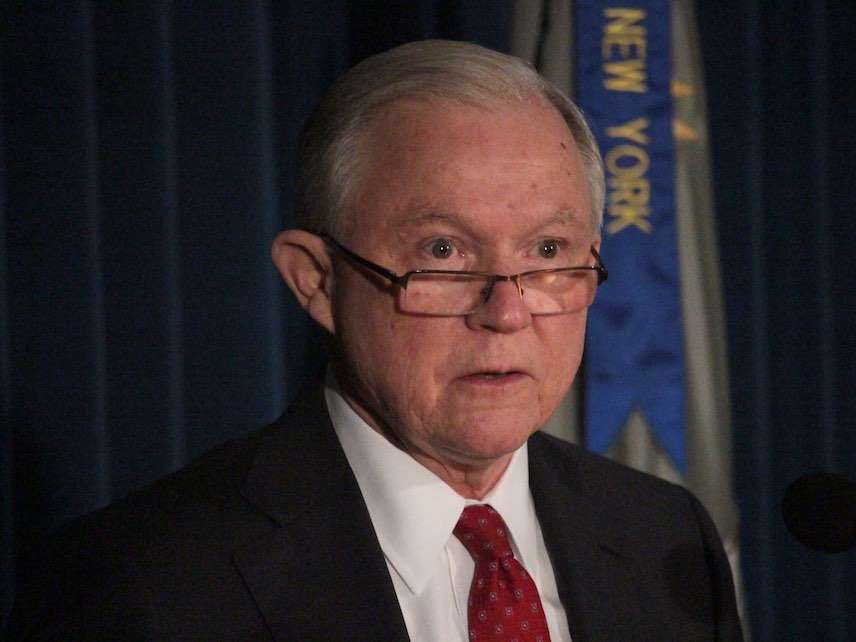

Jeff Sessions Used His Emergency Scheduling Powers Last Week. Here's What That Means.

Emergency scheduling won't fix the fentanyl crisis, no matter what Jeff Sessions claims.

We're about to see a sea change in how the feds plan to tackle overdose deaths, and it will likely have some very ugly unintended consequences. The Department of Justice (DOJ) announced last week that it has used its emergency scheduling powers to place all fentanyl analogs in schedule I.

What does that mean? Glad you asked:

What is emergency scheduling?

The Controlled Substances Act allows the attorney general "to temporarily place a substance into Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act for two years" without the consent of any other federal body "if he finds that such action is necessary to avoid an imminent hazard to the public safety." The Justice Department used emergency scheduling to place MDMA in schedule I in the 1980s. Physicians challenged that decision at the time, and lost. Absent emergency scheduling, getting a drug into or out of any scheduling category requires either legislation or a "scientific and medical evaluation" by the Department Health and Human Services.

Why is the DOJ using its emergency powers?

Under federal law, the Justice Department can prosecute a person for drug trafficking if the drug in question is a controlled substance, or if an unscheduled drug closely resembles a controlled substance and is intended to mimic it. Fentanyl, a highly potent analgesic used in surgeries and for pain management, is in schedule II, which is the legal and regulatory category for drugs with proven medical benefits that are also habit-forming, potentially dangerous, and prone to abuse. But many of fentanyl's analogs—drugs that are chemically different but work in a similar way—are not scheduled. And that makes prosecuting analog cases harder.

Consider marijuana. Prosecuting a marijuana case requires proving only that the drug being sold was marijuana. But prosecuting a marijuana analog case, absent that specific compound having already been scheduled, requires proving that the drug in question is either chemically similar to marijuana or produces similar effects, and is intended for human consumption. This is why synthetic marijuana is frequently labeled as potpourri and why synthetic cathinones are marketed as bath salts.

In short, prosecuting drug analog cases is a pain in the ass.

Prosecutors have two particular reasons to dislike current federal analog laws. One is that chemists make new analogs faster than the feds can ban them. Between 2009 and 2014, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) identified 233 new synthetic drugs in the American market that were designed to mimic the effects of controlled substances. But according to a 2014 presentation delivered by DEA agents at the National Conference on Pharmaceutical and Chemical Diversion, the process of adding analogs to the drug schedule lags far behind the development and importation of new compounds:

To get a new compound on the schedule, the DEA has to analyze the compound, describe its chemical structure, and explain how it relates to an already scheduled drug. That's labor-intensive work, and the DOJ doesn't want to do it for every compound it comes across. There are a lot of analogs, and some of them may not be circulating in large enough volumes to justify the work that goes into identifying and then prohibiting them.

The second reason prosecutors don't like the current laws is that drugs that haven't gone through scheduling process essentially have to be litigated. Courts have divided over the chemistry arguments made by prosecutors, and even when DOJ prevails, due process is still arduous.

"The chemical composition of these drugs is ever evolving, and the current legal framework (both the statutes and the guidelines) is inadequate to ensure that the criminals who sell these deadly poisons face appropriate punishment," the Justice Department complained in a July letter to the United States Sentencing Commission. The current process for determining the sentencing range for analogs "is cumbersome, inefficient, and resource-intensive. It turns sentencing hearings into lengthy chemistry and pharmacology lectures, often complete with dueling experts. This process has led to inconsistent and inadequate determinations of offense severity."

Rather than require prosecutors to demonstrate to judges that an analog is "substantially similar" to a restricted substance—in other words, that a fentanyl analog is chemically similar to fentanyl—the Justice Department wants the sentencing commission to rewrite the guidelines so that "if the Attorney General has published (through either permanent or temporary scheduling) an equivalency to a controlled substance, that equivalency should be followed." If the commission won't do that, the DOJ wants it to create a broad system in which drug equivalency is determined by class, rather than require prosecutors to determine equivalency on a drug by drug basis.

Basically, the DOJ is taking a two-pronged approach. It's petitioning for help making sentencing faster and easier, and it's using the emergency scheduling power to broaden its policing powers.

"When the DEA's order takes effect," reads the agency announcement from last week, "anyone who possesses, imports, distributes, or manufactures any illicit fentanyl analogue will be subject to criminal prosecution in the same manner as for fentanyl and other controlled substances. The action announced today will make it easier for federal prosecutors and agents to prosecute traffickers of all forms of fentanyl-related substances."

The key phrase here is "easier for federal prosecutors and agents to prosecute traffickers."

Will any of this actually make a difference in how many people die from fentanyl?

Did I mention that the DOJ has already used emergency scheduling to put other fentanyl analogs in schedule I? This latest action is the broadest one yet, but the previous declarations haven't made a dent in illicit opioid importation. If Sessions believes this action will garner a different result, it might be because he's assuming analog producers are willing only to skirt the law, not actually break it.

In two recently unsealed indictments of Chinese nationals accused of exporting various analogs to the United States, the Justice Department claimed one of the men, Xiaobing Yan, "monitored legislation and law enforcement activities in the United States and China, modifying the chemical structure of the fentanyl analogues he produced to evade prosecution in the United States." Whatever attempts Yan made to comply with the letter of the law clearly didn't work, because the DOJ is now seeking his extradition from China for offenses that predate the last few rounds of emergency scheduling.

The profit margins for analogs are large enough that emergency scheduling won't drive producers out of the market, but it will incentivize tinkering. What opioids other than fentanyl can be modified? Law enforcement agents generally don't know the answer to that question until long after black market chemists have answered it. Emergency scheduling is today's reaction to last year's innovation.

If anything, emergency scheduling is likely to further endanger the lives and health of drug users. The DEA knows this. In its presentation to the National Conference on Pharmaceutical and Chemical Diversion, the DEA acknowledged that analogs "are often more dangerous than the traditional illicit drugs they are purported to mimic." Bath salts are less predictable than crystal methamphetamine, which is less predictable than prescription amphetamines. Make it harder to get the predictable stuff, and you drive users to the unpredictable stuff. People who understand analogs know this. John W. Huffman, who invented the first synthetic cannabinoids (with federal funding), says that marijuana is far safer than the compounds he created. This is even true of steroids. Restrictions of pharmaceutical-grade testosterone led to the creation and proliferation of prohormones, a class of drugs for which we have very little clinical data. When Congress banned those, the market responded by promoting non-medical use of selective androgen receptor modulators, or SARMs, about which we know even less.

Even if some of these analogs can be used safely, users have little reason to trust analogs they receive through the grey and black markets. Tracing provenance is incredibly difficult, batches of analogs vary in quality and content even when they come from the same producer, and the market is so anonymized across the supply chain that there are no mechanisms for enforcing quality control. The maker might know exactly what's in his batch, but he's not exactly declaring his shipment to customs or producing an ingredients label. The person who receives the package knows it's a drug that works like fentanyl (or whatever substance is being mimicked), but not what the right dosage is or what the side effects are. Information is continuously lost as the drug moves closer to the user. The person who puts an analog in their body likely knows only that it will get them high. That's true for all kinds of drugs, but legal substances are consumed in a context that makes it relatively safe for a user to know little more than dosage and expected effect.

Analogs are often dangerous and unpredictable, but they exist only because the government has prohibited the drugs they copy. Emergency scheduling will help prosecutors put more people in prison, but it won't keep Americans out of the morgue.

Show Comments (20)