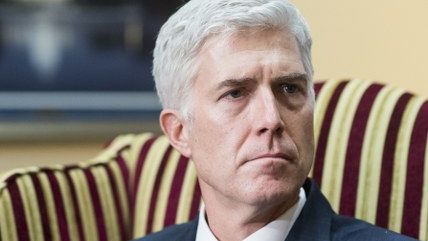

Does Gorsuch Stand with Scalia on Sodomy Laws?

An issue the Supreme Court candidate should address.

During his Senate confirmation hearings, Neil Gorsuch may be grilled on such legal topics as due process, enumerated powers and stare decisis. I'm hoping the discussion will also get around to a less arid subject: sodomy.

Not that I care what the Supreme Court nominee does under the sheets, and the dialogue I envision would probably qualify as PG-13. But his view of two major rulings on state laws banning certain types of sexual conduct is worth investigating. A candid discussion might make Americans wonder whether the judicial philosophy he upholds is quite as appealing as it sounds.

In nominating Gorsuch, President Donald Trump wanted to duplicate the late Justice Antonin Scalia's "image and genius." Gorsuch described Scalia, whose death created the vacancy he was chosen to fill, as a "lion of the law." In a speech last year, he embraced him as a model. Both Republicans and Democrats agree that the two are as different as Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen.

That brings us to the matter of sodomy. In 1986, shortly before Scalia joined the Supreme Court, the justices upheld a Georgia law making it a crime to seek gratification in oral or anal sex, gay or straight. The case arose after police arrested two men caught lustily violating that law in a private home.

"The Constitution does not confer a fundamental right upon homosexuals to engage in sodomy," said the court. Had he been a justice at the time, Scalia would have voted with the majority.

We know because he bitterly objected in 2003 when the court changed its mind. Striking down a Texas ban on homosexual sodomy, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that the two men challenging the law "were free as adults to engage in the private conduct in the exercise of their liberty under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment."

Conservatives denounced the decision as a case of judicial activism. Then-Sen. Rick Santorum, R-Pa., said it opened the way to legalizing incest. Evangelist Jerry Falwell called it "a tragedy for America."

What they were defending was a criminal statute telling grown-ups what they could do to gratify each other in bed. The very idea may sound preposterous now, but it wasn't then; 14 states had similar laws. Such medieval prohibitions would still be allowed if a certain sainted justice had gotten his way.

In a blistering dissent, Scalia insisted the state of Texas was perfectly entitled to outlaw "certain forms of sexual behavior" because it regards them as "immoral and unacceptable." In overturning the ban, he charged, the court had "signed on to the so-called homosexual agenda" and invited "a massive disruption of the current social order."

By the logic of his judicial philosophy of originalism—relying on what the words of the Constitution were understood to mean when it was ratified—his view was understandable.

After all, the words "oral sex" are flagrantly absent from the Constitution. He could also point to the long history of laws against oral and anal pleasuring and to the obligation of the court to follow precedents, notably the 1986 ruling.

So the question for a nominee who fervently champions Scalia's approach to judging is: What about sodomy?

The 2003 decision no longer gets much attention from conservatives. Scalia's caustic fulminations on the topic were left out of the eulogies. No Republican has endorsed Gorsuch on the grounds that he would uphold laws against gay sex.

But given the chance, why wouldn't he? If he reveres Scalia and his approach, it would be logical for him to agree that oral and anal sex can be banned. But to admit as much would alarm most Americans—who think that adult partners should be free to do whatever floats their boats.

To repudiate Scalia, however, would suggest there is something fundamentally defective in Gorsuch's entire approach to judging. It would imply that the late justice was not all-wise.

It would suggest that the principles established by the Framers can clash with conservative ideals. It would imply that the meaning of important constitutional provisions is not fixed for all time but evolves under the pressure of new circumstances and changing standards—and that judges have to acknowledge as much.

So by all means, let Gorsuch explain his view of those decisions. In doing so, he might reflect that what one New Orleans mayor said about prostitution applies as well to sodomy: You can make it illegal, but you can't make it unpopular.

© Copyright 2017 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

Show Comments (171)