Licensing Isn't Necessary To Protect People From Incompetent, Untrained, or Fraudulent Professionals

Sign language interpreters say licensing is needed to protect deaf people from scammers, but there's no evidence of a market failure.

Two weeks ago, I wrote about a nascent effort at occupational licensing reform in Wisconsin, where Republicans say they intend to use the 2017 legislative session to review state laws that hold the economy back.

In conjunction with that announcement, the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty, a Milwaukee-based free market think tank, published a report on six occupational licenses that should be repealed or reformed. The report highlighted licenses for dietitians, landscape architects, private detectives, private security persons, sign language interpreters, and interior designers.

None of these licenses do much, if anything, in the way of protecting the public's health and safety, I wrote at the time. Since that's the only reason government should require a permission slip before someone can engage in an otherwise legal activity, it makes sense that Wisconsin lawmakers should take a skeptical look at why those licenses are required.

The deaf community in Wisconsin, though, has been quick to criticize the idea of repealing the state license for sign language interpreters.

I've received more than a dozen emails from people in Wisconsin (and elsewhere) arguing that the state license for sign language interpreters is necessary and proper. I checked with the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty and found out that they, too, have been besieged by a similar outpouring of opposition since publishing their report.

Here's a portion of the message I received from one reader, Karen Beth Staller, who says she's been a sign language interpreter for 30 years:

While it's much more expensive and time-consuming to engage in the profession than it was when I started, it's time and money well-spent. We need degrees, licenses, registrations and background checks, as well as continuing education requirements to keep up with developments in linguistics and interpreting practices, as well as training interpreting in specialized settings.

As a freelance interpreter, one might go into a college classroom for a class on legal ethics or microbiology; a doctor's office for a cold or a cancer diagnosis; an operating room for open heart surgery; a courtroom for a divorce hearing or a murder trial; a factory floor for a job interview or forklift training; an emergency room for a broken toe or a shooting; a bank to liquidate a deceased relative's accounts; a funeral home to make final arrangements; and hundreds of other settings for myriad other reasons…

…This may seem simple to someone who has - as a hearing person - dealt with these interactions all your life, but when there's a language difference, it becomes more complicated…

…To become an interpreter, one needs much more than just a knowledge of sign language, but without background checks, licenses and educational requirements, anyone would be able to call themselves an interpreter."

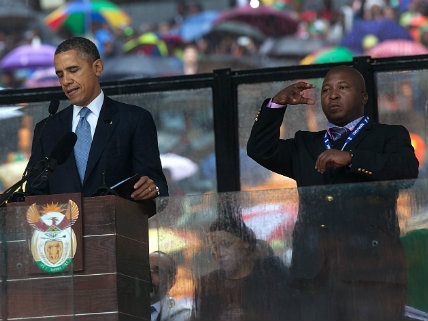

I think Staller made the strongest argument out of the messages I received, but there were many variations of the "if we don't have a license, anyone can call themselves an interpreter and cause confusion or outright harm to the deaf community." Several of those messages included references to the 2013 incident in which a man named Thamsanqa Jantjie ended up on stage with President Barack Obama during Nelson Mandela's memorial service in South Africa. Jantjie clearly had no idea what he was doing and was obviously not a trained sign language interpreter, to say the least.

That Jantjie was apparently able to fake his credentials well enough to get on stage at such a high-profile event certainly is shocking, but it's not a good argument for licensing. It speaks more to a lack of adequate diligence by the organizers of that single event, not to a broader problem in the market for sign language interpreters. In other words, just because South Africa does not require licenses for sign language interpreters, it doesn't mean that a licensing scheme would have stopped Jantije from getting on stage.

No one is arguing that deaf people do not have a right to have skilled, accurate interpreters. The question, then, is not whether the deaf community in Wisconsin should have access to competent sign language interpreters, but whether a state licensing scheme is the best way to ensure that they do.

"The importance of sign language interpreters' work is not at issue," says Lee McGrath, legislative counsel for the Institute for Justice, a libertarian law firm that frequently challenges restrictive and onerous state licensing rules. "The real question is whether there is some permanent market failure that courts, hospitals, or businesses are unable to determine whether an interpreter is competent."

Most states don't require a government-issued permission slip for sign language interpreters. Until 2010, Wisconsin didn't, either. Even if fake sign language interpreters are a legitimate concern in Wisconsin, it's not clear that a market failure exists because there isn't a scourge of poor sign language interpretation affecting other part of the country. It would seem there must be other mechanisms to prevent Jantjie-style scam artists from ruining the lives of deaf people.

There's actually lots of them. Private certifications are probably the best way to accomplish the goals of licensing (efficacy and competency in a professional workforce) without getting the government involved. There's a national organization, the Registry for Interpreters of the Deaf, already offering this certification.

As the website for RID's Ohio Chapter informs: "While Ohio does not yet require a degree or certification to interpret outside of the K-12 classroom setting, to gain competence in interpreting, one should consider enrolling in an Interpreter Training Program."

Translation: If you want to get a job being a sign language interpreter in Ohio, get certified because no one will hire you otherwise.

There are other market-based regulatory mechanisms too, particularly in today's world where everything can be subject to an online review. This is clearly an issue of importance to the deaf community in Wisconsin, so I don't doubt they would be able to police bad actors and prevent them from finding work. In many ways, this more personalized, market-based regulation can offer superior results compared to what you get with government licensing. Getting a license means you cleared the bar set by bureaucrats in Madison (or somewhere else), but that's all. It's binary. Black and white, on or off, yes or no.

Market based regulations or private certifications allow consumers to see a range of results. It filters out the bad guys, but it also lets the really good ones stand out from the crowd.

"The issue is not whether sign language interpreters are important or whether it matters if interpretation is accurate. It is our view that free markets, informed with good information, are the most efficient means at ensuring quality – not government permission slips," says Collin Roth, a research fellow at the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty. "Fencing out interpreters who may be well qualified but are not in a position to bear the costs and burdens of licensure is, in our view, more likely to deny the deaf community the services that it needs – and drive up the cost of those services – than it is to materially improve public and safety,"

If all else fails and there is a real concern about people passing themselves off, Jantjie-style, as fake sign language interpreters, lawmakers can always make that a crime and empower the state attorney general to prosecute such frauds.

That should be a last resort, of course, but it's still better than licensing because it only punishes those who are actually breaking the law. Licensing operates under the premise that government permitting will prevent potential law-breakers from ever having the chance to do so by erecting a barrier to entry. The problem is that everyone—including the vast majority of people who aren't going to commit that sort of fraud—has to clear that same barrier.

"State legislators should insert themselves between provider and buyer only when there is a problem that private actors cannot fix," McGrath told me via email. "Moreover, when the state does intervene, it should be in the least restrictive way."

More restrictive methods, like licensing, restrict competition, hurt opportunities for workers, and raise consumer prices. Licensing cost Wisconsin more than 30,000 jobs over the last 20 years and adds an additional $1.9 billion annually in consumer costs, according to the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty report. Sign language interpreter licensing probably accounts for only a tiny part of that cost, but Staller admits that "it's much more expensive and time-consuming" to be an interpreter today than it was decades ago when she started working in the field.

Deaf people everywhere should have access to high-quality, well-trained sign language interpreters and should be protected against frauds. The question lawmakers in Wisconsin (and elsewhere) should be asking themselves is whether mandatory government permission slips are the best way to accomplish that.

Show Comments (48)