The Worst Part of Election 2016? Nothing Is Over on Tuesday, Nothing!

Whether Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump becomes president, American trust and confidence in government will keep dropping. And that's a big problem.

If you think that much of anything related to politics will be settled by Tuesday's election, here's some bad news for you: Nothing that matters is really over. Not even close.

There are at least three major issues that will still be facing the country when either President Clinton or President Trump gets sworn in next January. There's no reason to believe that these issues will resolve themselves any time soon. Or that Clinton or Trump, the two most-hated presidential candidates in modern history, are particularly willing or able to address them.

1. What about economic growth?

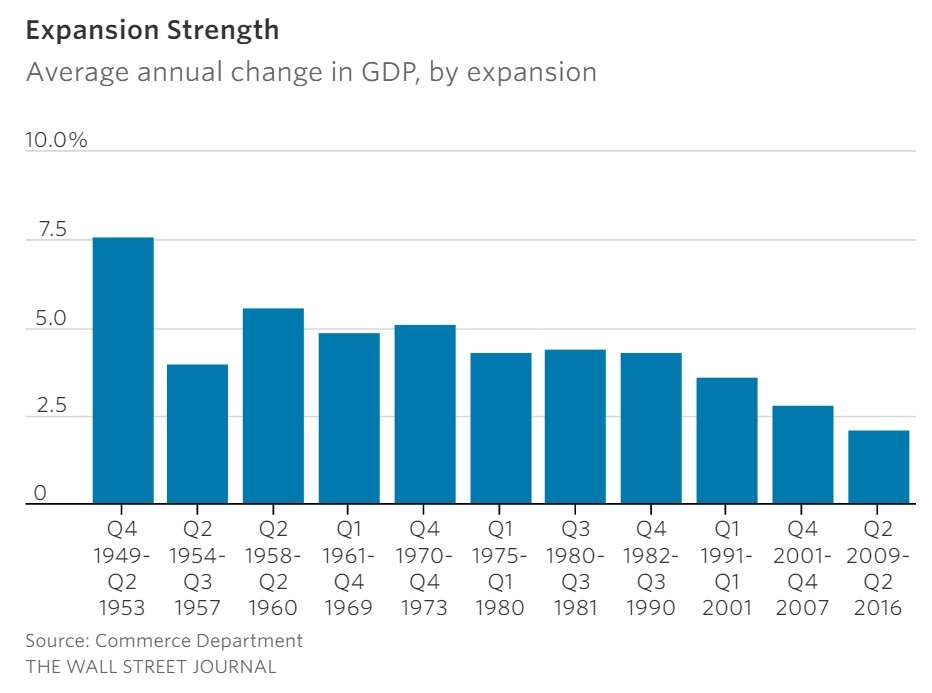

The United States has been out of recession for seven years, one of the longest economic expansions in American history. But the average rate of growth since 2009 has been around 2 percent, making this the weakest economic recovery since 1949.

Economic growth is essential to improving wealth and standards of living—and it helps to defuse all sorts of explosive political issues, from trade to immigration to welfare. But for all of the 21st century—under George Bush and Barack Obama—economic growth has been much lower than the post-war average, helping to fuel political polarization.

Neither Hillary Clinton nor Donald Trump has articulated a plan that will actually grow the economy. Clinton will jack up taxes and spending on everything, a sure-fire way to keep the economy puttering along. Trump will add $5 trillion-plus dollars to the national debt, which will also dampen growth. According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, under Clinton's scenario, national debt held by the public will grow from 77 percent of GDP to 86 percent over the next decade. Under Trump's, it will increase to 105 percent. Robust economic growth is unlikely, to say the least, under such plans.

And if the American economy doesn't improve, don't expect much else too. Economic conditions don't dictate everything, but there's a lot less anger and resentment in a society where economic growth is strong.

2. Who will we bomb next?

Hillary Clinton is a hawk's hawk who has voted for, lobbied for, or taken credit for all of our military interventions in the 21st century. Despite such actions—of more accurately, because of such actions—the world is a bigger mess than ever. At times Donald Trump sounds like he would be a relative dove and at others, he sounds like a crazy man who will kill them all and let god take his own. At the very least, just like Hillary Clinton, he's promised to increase military spending, which will keep the deep-state dynamics of interventionism exactly as they are.

Neither of them has articulated a foreign policy that will reduce international terrorism or bring calm to hot spots in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, or Asia any time soon.

3. Whom can you trust?

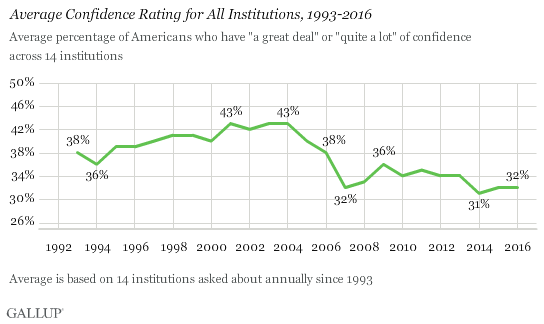

Trust in many major American institutions is at or near historic lows—the media, religious organizations, labor, business—you name it.

That's especially when it comes to the two major political parties and government in general. Looking at surveys going back to 1958, Pew Research concludes,

Only 19% of Americans today say they can trust the government in Washington to do what is right "just about always" (3%) or "most of the time" (16%).

Even worse, millennials—Americans between about 18 and 35 years old—aren't just the biggest generation, they are the most skeptical and least-trusting.

Who can blame them—or us? The Iraq War was sold on bad information and prosecuted poorly; President Obama's claim that his health care reform would let you keep your doctor was Politifact's Lie of the Year; and we've learned that neither Democrats nor Republicans give a rat's ass about the government spying on us. Wikileaks and others have exposed Hillary Clinton as two-faced (at best) and Donald Trump is a serial scam artist and bully. Neither can address the massive and ongoing evacuation of trust and confidence in government and politics. If anything, they will likely pour gas on the dumpster fire.

For the entirety of the 21st century (and for much of the post-World War II era), America has been moving from a high-trust society to a low-trust one. That's really bad news, especially for those of us who want a government that spends less and does less. Paradoxically, people in low-trust countries turn to government in ever-higher numbers. In a cruel and unpredictable world, we want a protector, no matter how untrustworthy. Or we just want someone we think will make sure that we get most of our slice of what we think is a shrinking pie.

In the 2010 paper "Regulation and Distrust," Philippe Aghion, Yann Algan, Pierre Cahuc, and Andrei Shleifer use World Values Survey data to help explain what they call "one of the central puzzles in research on political beliefs: Why do people in countries with bad governments want more government intervention?" In "high-trust countries," most people have positive feelings about business and government and the general level of regulation is relatively low. In "low-trust countries," the opposite is true and citizens "support government regulation, fully recognizing that such regulation leads to corruption." In low-trust countries such as Russia and the former East Germany, for instance, around 90 percent and 80 percent of people favor wage controls. In Scandinavia, Great Britain, and North American countries, where there are higher levels of trust in the public and private sectors, less than half the population does. Aghion et al. find that increased regulation sows yet more distrust, which in turn engenders more regulation.

Of course, it doesn't have to be this way. Politicians and their ideological allies can actually start acting responsibly and putting forth serious plans for reducing the size, scope, and spending of government. Gary Johnson and Bill Weld did do precisely this—the two former governors spoke not of zero government but a smaller government that did fewer things more effectively—but they hardly set the electoral map on fire, regardless of what will certainly be a record showing for the Libertarian Party. Figures such as Sen. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) have refused to fall in line with tired and fading party loyalties by calling for a hearing on Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland and voting for his party's candidate. Such characters are few and far between, but there are enough elected officials in each party to at least push, I don't know, an actual budget process forward.

Until the major parties start governing in the light of day and especially stop nominating candidates who are disliked by majorities of Americans, don't expect much to change. Except for things to get even nastier, at least until 2020.

Show Comments (97)