Ross Ulbricht's Conviction, Sentencing for Running Silk Road Should be Overturned, Argues New Reply Brief

Ulbricht's lawyer claims corruption on part of investigators, bad evidentiary decisions, Fourth Amendment violations, and grossly unreasonable sentencing demand reversal, new trial, or resentencing.

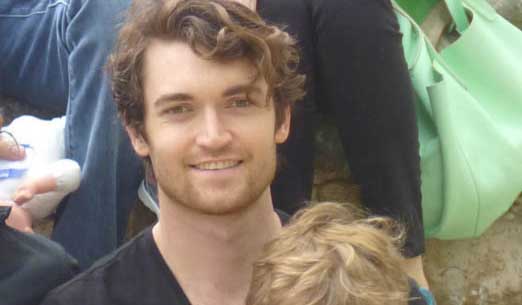

The defense team for Ross Ulbricht, convicted and sentenced to life in prison without parole for his role in starting and running the darkweb sales site Silk Road, has filed a new reply brief in the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals in their appeal of his conviction and sentence.

Overarchingly, Ulbricht's lawyer Joshua Dratel thinks abundant evidence of corruption in the investigation of Ulbricht that was not properly considered by the trial judge leads to his conclusion that Ulbricht's "convictions should be reversed, and a new trial ordered, and/or that certain evidence be suppressed, and/or that the case be remanded for re-sentencing before a different district judge."

Two of the investigating agents, Carl Force of the DEA and Shaun Bridges of the Secret Service, have since Ulbricht's arrest both themselves been arrested for crimes related to their investigation.

Dratel in the brief notes that, despite later government attempts to separate Force, after his arrest, from the core of the case against Ulbricht, that "The United States Marshals' Intake Form for Ulbricht, completed upon his arrest October 2, 2013, lists under the "Arrested or Received Information" section, as the only law enforcement officer, "Carl Force"…

Information that has since arisen from the cases against Force and Bridges that Dratel thinks should have been relevant to Ulbricht's conviction include that "[w]hile at the Secret Service [Bridges] specialized in, among other things, use of the Dark Net and identity theft." and that "(Bridges "committed crimes over the course of many months (if not years). . . . [and] "was an extremely calculated effort, designed to avoid detection for as long as possible, ironically using the very skills (e.g., computer skills) that he learned on the job and at the public's expense."

Some specific examples of Bridges using his role as an investigator of Silk Road to rob:

As the government explained in its Sentencing Memorandum, "Bridges stole bitcoins from various Silk Road accounts using the log-in credentials from one of the website's customer support representatives – a target whom they had arrested – and transferred the bitcoins to Mt. Gox, an offshore bitcoin exchange company in Japan [owned and operated by Mark Karpeles, whom the defense identified as DPR]." ….

particularly relevant to the defense here, Bridges took deliberate affirmative steps to deflect blame from himself onto others, regardless of potential consequences for them. Thus, Bridges sought to "lay the blame for that theft on a cooperating witness [Curtis Green, a/k/a "Flush"]." ….

Bridges "later that day[] accessed Silk Road through a computer utilizing [Green's] administrator access. Bridges reset the passwords and pins of various accounts on Silk Road and moved bitcoin from those accounts into a 'wallet' he controlled." ….Green pointed out that "when [Bridges] moved the bitcoins he moved them into my account so it really looked like I did it. I mean, anybody looking into it would – it would be a no-brainer, saying, 'Oh, obviously he did it.'"

Very key to the defense contention that Bridges' involvement should have contaminated the case against Ulbricht:

At Bridges's sentencing the government also described how Bridges's corruption had affected investigations in which he had participated: "[t]he number of cases that Mr. Bridges contaminated, not just existing criminal cases, but also investigations across the country that his conduct has let to have to be shut down, is truly staggering. We start here – there was a criminal investigation that another district had into Mt. Gox that's had to since be shut down."…."[b]ut that's just one example. I can tell you from my own knowledge that in this district a number of investigations have had to be shut down directly – directly, a hundred percent, because of Bridges."

Given how much of the evidence linking Ulbricht to the "Dread Pirate Roberts" who committed the crimes in question came via Bridges, Dratel thinks fair consideration of their shenanigans is necessary for a fair trial for Ulbricht. As he writes, after quoting the above about government recognition of Bridges' contamination of other cases:

Yet here [in Ulbricht's case], in which Bridges was actively and directly corrupt with respect to the website under investigation, in which he operated corruptly inside the web site, manipulating its data and access protocols, communicating surreptitiously with its operator (DPR), and profited from it, somehow, according to the government, that is not sufficient connection to be relevant, or have an effect on the case. Indeed, the government acknowledged at Bridges's sentencing that the extent of his criminality and intrusion remain unknown….

Dratel excoriates the government for, in its brief to which this one is a reply:

mak[ing] three grossly, and materially, inaccurate assertions: (1) Ulbricht "has not identified any suppressed, exculpatory information."….incredibly, that ignores the government's complete failure to disclose Bridges's corruption in the Silk Road investigation, or to address it in its Brief; (2) "Force played no role in the investigation of Silk Road conducted by this Office." ….Yet, the Marshals Intake Form, the information set forth above, as well as the facts set forth in Ulbricht's Initial Brief….dispositively refute that claim; (3) Force "was never contemplated as a witness at trial."….Yet, in its Brief….the government concedes otherwise: "[a]lthough the Government indicated during pretrial proceedings that it would seek to admit Ulbricht's communications concerning this murder for hire (A. 664), at trial, the Government did not seek to admit any aspect of either this attempted murder or Ulbricht's communications about it, including with Force." Notwithstanding the government's strategic choices, it cannot deprive Force and his corruption (or Bridges's) of relevance by that evidentiary sleight of hand….

That Bridges was even under criminal investigation was not known to Ulbricht's defense until after the trial.

The brief also discusses possible evidence indicating there might be something to the defense's alternate theory that Mt. Gox founder Mark Karpeles may have been the real Dread Pirate Roberts during the criminal investigation ending in Ulbricht's arrest (though Ulbricht admits to founding Silk Road), including that there exist:

multiple warrants, including in the Southern District of New York, signed by the prosecutor in this very case, attesting that the evidence established probable cause that Karpeles – formally denominated a target of the investigation – was the operator and proprietor of the Silk Road website….Nor was that merely a fleeting assertion; rather, the warrants averring probable cause spanned more than a year, even until August 2013, just six weeks before Ulbricht's arrest (which halted the pursuit of Karpeles entirely).

Dratel also argues that the court refusing to permit him to cross-examine certain witnesses about certain technical points also illegitimately hobbled Ulbricht's defense. This is vital because:

it is not surprising that the government can argue in its Brief that its evidence was in many respects unrebutted….because the opportunity to do so was foreclosed by the District Court's evidentiary rulings. Thus, the government's assertion….that "[s]ubsequent examination of the defendant's computer revealed voluminous evidence tying the defendant to the creation, ownership, and operation of Silk Road for the length of its existence[,]" was dependent entirely on the evidentiary rulings that prevented the defense from challenging the integrity and reliability of that digital evidence, for which there was not any firsthand or direct testimony establishing that Ulbricht created the documents on the laptop, or that they were created at the time of the claimed computer time stamp (which testimony acknowledged could be changed)…

Judge Katherine Forrest also illegitimately disallowed two defense witnesses Dratel wanted to bring forward in trial, the reply brief insists. "The District Court abused its discretion in precluding the two defense experts," Dratel wrote, "especially when their testimony was rendered necessary by the government's late notice as well as the limitations the District Court imposed on cross-examination of government witnesses."

Dratel called on the doctrine of "cumulative error":

The doctrine of cumulative error….attains enhanced importance here because of the government's persistent attempts to isolate each issue in performing "harmless error" analysis. While…the individual errors were not harmless beyond a reasonable doubt, when aggregated they represent a complete evisceration of the ability to present a defense, and are patently not harmless. The evidentiary errors created a one-sided trial in which the defense was precluded from even investigating, much less using, material exculpatory evidence (POINT I), unduly restricted in pursuing cross-examination with respect to several witnesses (POINT II), precluded from responding to the government's case – including testimony and voluminous exhibits provided only mid-trial – with relevant and admissible expert testimony (POINT III), and precluded from introducing admissible, credible evidence that supported the heart of the defense theory (POINT IV).

The brief also argues that the searches of Ulbricht's digital life violate the Fourth Amendment principle of particularity, and mocks the government's counterargument:

the government posits two extraordinary concepts that would eliminate the particularity requirement altogether. For example….the government maintains that Ulbricht's electronic data was seized en masse "justifiably [], because even innocent communications or travel records might contain details overlapping with 'DPR's (innocent) statements, shoring up the proof against Ulbricht."

That construction, however, would dispense with particularity in any and every investigation because anything could be relevant to everything – thereby obliterating the essence of particularity. In ACLU v. Clapper….this Court noted that a definition of prospective relevance that was so elastic it defied limitation was no definition at all. Here, the same is true with respect to the warrants' lack of any narrowing principle that would conform with the particularity requirement – infecting both the applications for and execution of the warrants.

The government also advances the proposition that a warrant can be justified by the fruits of the search and seizure…that "[a]nd, as the application foreshadowed, the warrant yielded additional evidence of this type establishing Ulbricht's identity beyond a reasonable doubt at trial." Yet that post hoc rationale was soundly rejected in Steagald v. United States….citing Stanford v. Texas…Nor should the government be rewarded for an unlawful warrant simply because a more tailored warrant would have passed constitutional muster…..Otherwise, the government would be encouraged always to engage in unlawful search and seizure confident that only the unlawfully seized items would be suppressed.

Dratel has also argued that "the Pen Register and Trap and Trace Order [in Ulbricht's case] were unlawful because they required a warrant and/or failed to adhere to statutory limitations." He denies the government's contention that "Internet Protocol ("IP") addresses do not provide content" since "Once an investigator has an IP address, the very same content of that website that the subject of the surveillance observed is equally available" unlike with a telephone pen register that would not reveal the content of a call.

He also in this reply brief calls on the very recent case of United States v. Lambis in which "a District Court suppressed evidence obtained via a cell-site simulator (also called a "Stingray" device) that prompts cell phones to provide their location, finding that acquisition of such data requires a warrant."

Dratel analogizes that decision to Ulbricht's case. "Ulbricht makes that same argument with respect to the Pen Register and Internet routing information obtained absent a warrant," Dratel wrote:

As the Court in Lambis declared…"the Government may not turn a citizen's cell phone into a tracking device."….Here, the same is true with respect to functionally indistinguishable means of geo-locating Ulbricht's laptop computer….The Court in Lambis also held that the limitations of the "third-party doctrine" did not apply…..Although distinguishing a cell-site simulator from a traditional pen register, id., here the pen register and trap and trace devices, combining the location of the router with the activity of Ulbricht's laptop while he used it at home, operated in the same manner.

The reply brief also says the government failed to adequately defend the procedural reasonableness of Ulbricht's life sentence without parole:

in an attempt to defend the District Court's use of a criterion not based on any established or cited precedent or procedural rule to shoehorn into Ulbricht's sentence a series of alleged overdose deaths which cannot be established were caused by drugs purchased on the Silk Road website, the government refers to various legal standards in an attempt to find one, or some combination of standards, that could encompass the District Court's analysis. Nevertheless, the government cannot save the District Court's vague and subjective analysis by cobbling together a new standard from a series of established standards, all of which the District Court failed to employ….. If the District Court had applied a single, cognizable, proper standard there would not have been any need to devote nearly five pages, including a nearly three-page footnote, to discussing various standards upon which the District Court might have relied…..

While the government argued at sentencing, and again it its Brief that "[t]he proliferation of 'dark markets' in the wake of Silk Road's founding underscored the need for general deterrence"…the continued growth and emergence of new "dark markets," even after Ulbricht's life sentence was imposed May 29, 2015, demonstrates that general deterrence, especially in this instance, is entirely illusory and a component of sentencing that defies measurement and comparison, and therefore guarantees disparity….

…."general deterrence" is the illusory tail wagging the very real dog – the life sentence. Despite the objective evidence – both academic and clinical – that longer sentences do not deter, the District Court rejected that conclusion without citation to any contrary authority.

Dratel goes on to detail some of the substantially shorter sentences, some as low as five years, received by those who actually sold drugs on the Silk Road, which Ulbricht did not. Given that Judge Forrest's sentence seemed based on some factors for which Ulbricht was not charged, including alleged deaths caused by drugs bought on Silk Road or alleged but unadjudicated "murders for hire," Dratel summons various precedents to insist:

a long sentence, such as a life sentence, based solely on judicial factfinding regarding "uncharged conduct . . . seems a dubious infringement of the rights to due process and to a jury trial" is directly applicable here, as the District Court reached factual conclusions as to uncharged conduct, including murder for hire allegations and alleged overdose deaths, and used these facts to justify the life sentence it imposed.

Earlier reporting on the appeal and the conviction of Ulbricht.

My history of the case against him, reported and written before the trial began.

Show Comments (136)