Entrepreneurial Spirit Has Abandoned Non-Urban America: Bug or Feature?

Imagine what will happen to flyover country under even more wage regulations.

Pretty much every story describing the state of the American economy these days has a subtextual—if not outright stated—message: "This is why Donald Trump is happening." So it goes with a new report mapping out how America has recovered from the recession of the last decade. We are seeing significant fracture between urban areas and non-urban or rural environments when looking at the creation of new businesses. Entrepreneurship is becoming increasingly consolidated in major city centers. And even after the economy began recovering, new business creation did not return to previous levels in less-populated environments.

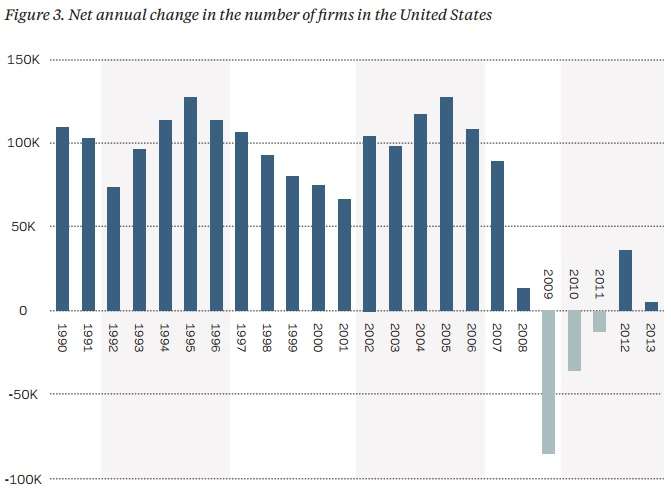

The report is by the Economic Innovation Group, a pro-entrepreneurship advocacy group. Their report, the "New Map of Economic Growth and Recovery," shows that the creation of new businesses in general has plunged compared to previous years going back to 1992. And yes, that includes previous smaller recessions like the dot-com bust. Their numbers show more new firms being created in 2001 and 2002 than in 2012 and 2013.

The report has a big focus on geography, and what it shows is that to the extent that new business creation has recovered, it has done so in a smaller number of areas than in previous examples of economic recovery. They've determined that fully half of new businesses established in the United States between 2010 to 2014 were in only 20 counties. And, of course, these are generally not counties out in the sticks. These are counties that are connected to major metropolitan areas. And while one might assume that areas with higher populations would naturally be responsible for creating more new firms, this is still a massive narrowing of opportunity. In the mid-'90s, half of all new businesses were scattered across 125 counties. Just prior to the burst of the housing bubble, half of new businesses were scattered to 64 counties.

Michael Coren at Quartz notes the disparities and brings in Trump, like you do:

Particularly hard hit were sparsely populated, rural areas. In the last post-recession recovery, counties with 100,000 or fewer people generated one-third of the country's new firms (net) between 1992-96. By comparison, those counties lost 1.2% of their businesses between 2010-2014.

The second story is that the majority of new companies look more like tech companies than the construction firms and restaurants that have typically anchored middle-class prosperity. New business formation over the past five years tracked very closely with access to capital, particularly venture and other forms of risk capital, says the report. Of the top 20 counties, 13 were in just three states (California, New York, and Texas) with ample access to such money. That shift has given highly educated urban dwellers another advantage at the expense of everyone else, a disparity polls suggest is fueling the rise of Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump among working-class, rural Americans.

Coren adds that the housing collapse resulted in decreased access to loans in these communities, and the plunge in housing prices also damaged people's equity in their homes and their savings, and people in these environments no longer had enough personal wealth to attempt to start their own businesses.

There's a lot more, as well. Municipal governments large and small have made it increasingly hard for new, small business creation to happen, with an explosive number of regulations, fees, and licensing requirements. Occupational licensing, which once only affected a small number of workers, now affects one out of four jobs, with government-mandated training and fees that drive up costs for both people wanting to enter the job market and for people who want to start businesses.

And to reiterate, this is also what is so utterly destructive to the idea of a state-wide or national $15 minimum wage and President Barack Obama's proposed rule to increase the number of people who would be covered under federal overtime laws instead of as salaried employees. Both of these proposals will have devastating impacts for smaller businesses in less wealthy communities, where both flexibility and thriftiness are necessary to survival.

Fareed Zakaria looked at this drop in businesses in the Washington Post and noted the impacts on regulation growth and how it favored entrenched firms that have been around for a while and could afford to deal with (and influence) government meddling. And then he quickly goes off the rails with some self-aggrandizing generational nonsense:

But a less-noted factor that might be crucial is generational. Baby boomers have proved to be great entrepreneurs, launching companies when they were young and keeping at it as they aged. Succeeding generations have been much less likely to found their own firms. Leigh Buchanan, citing Kauffman data, has explained that the percentage of start-ups launched by people in their 20s and 30s fell from 35 percent in 1996 to 18 percent in 2014. Meanwhile, the share founded by people in their 50s and 60s has actually increased over the past decade.

Young people today dress like Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, consume technology voraciously and talk about disruptive innovation. But they want to work at Goldman Sachs, McKinsey and Google. They are earnest, intelligent, accomplished — and risk-averse.

Is this caution born out of years of stagnant incomes, the financial crisis and a sluggish economy? Maybe, but I think there is something broader at work. Baby boomers were shaped by the 1960s and its counterculture. They were told to "tune in" to their passions and "drop out" of the old establishment. They were rebellious about everything — politics, parental authority, old-fashioned morality and big institutions. Their willingness to strike out on their own was not a pose to get venture capital funding. It was an expression of their passion.

First of all, thanks for erasing Generation X entirely. I'm sure we all had absolutely nothing to do with the launch of new businesses in the 1990s (when many of us were in our 20s, not baby boomers).

Second, who is responsible for that regulatory regime that is strangling the creation of new businesses for the benefit of entrenched government, corporate, and labor interests? Here's a hint: It's not millennials. When all was said and done, baby boomers hardly "dropped out" of the old establishment. They became the establishment, just like every generation does as it ages. The student loans that millennials are racking up now (which probably hamper their ability to engage in post-college risk) are lining the pockets and pensions of a growing administrative class at colleges, money being shifted to baby boomers and Gen. Xers. Our entitlement system, far from being a "safety net," has become a money transfer from the young to the old, even as the post-65 crowd are seeing their income status improve to a greater degree than any other demographic in the United States (while millennials actually lose ground).

Zakaria's absurd generational chin-stroking here (and again, his complete erasure of the generation that made start-up culture actually function) ignores the culpability of the members of the baby boomer establishment in holding new business development back. And it has nothing to do with an "expression of their passion" other than a desire to bend the tools of government to serve themselves.

Show Comments (32)