Chicago Students Vow to Destroy 'Hate Speech' As Soon As They Figure Out What It Is

What is hate speech? The aptly-named Chicago Maroon has no idea.

What is hate speech? The aptly-named Chicago Maroon has no idea.

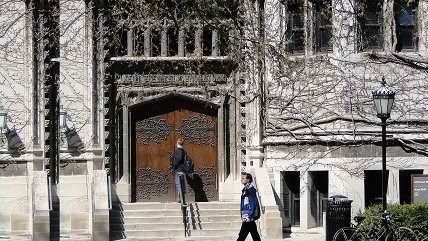

The University of Chicago's Committee on Free Expression recently published a surprisingly unqualified defense of free speech on campus (surprising only because university commissions are often hostile to speech and the group's name was fairly Orwellian). Its authors noted the university's rich history of bringing controversial speakers to campus for the sake of exposing students to a truly wide-range of ideas.

In response, The Maroon—a student newspaper—ran an editorial requesting clarification from the committee. Because free speech is all well and good, but what about hate speech? Obviously, we can't have any of that. Someone's feelings could get hurt. The editorial demands that the university do a better job separating good speech from bad speech, thereby protecting the community:

The University needs to clearly differentiate hate speech and offensive speech. Hate speech is defined as "speech that offends, threatens, or insults groups, based on race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, disability, or other traits," according to the American Bar Association. The report's failure to clearly define hate speech implies that all speech short of unlawful harassment is acceptable, no matter how vile or cruel. While it is important for students to challenge each other's opinions, this should not come at the expense of students' mental well-being or safety. …

Freedom of expression is essential to a productive and creative learning environment. This means students must be prepared to listen to opinions that differ from their own. Speech that challenges commonly held assumptions can be beneficial. Hate speech benefits no one because it seeks only to tear down, not to build up. The University needs to directly address hate speech for the good of productive discourse.

Unfortunately—or quite fortunately, depending upon your perspective—The Maroon's definition of hate speech is hopelessly subjective. Who gets to decide whether certain kinds of speech reasonably contribute to a person's mental anguish? And the assertion that hate speech serves no public use is simply untrue. We learn as much from listening to ideas that we vigorously oppose as we do from ideas that we already hold to be true.

The university's only obligation with respect to hate speech is to make sure everyone on campus knows that all speech—even the confrontational and irritating kind—is protected under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. But according to the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, many college administrators do a terrible job of communicating these fundamental freedoms to their students. And clearly some students have no respect for such freedoms, in any case.

The Charlie Hebdo attack has thrust the issue of censorship into the public spotlight. Many Americans are saying "Je Suis Charlie" to show solidarity with the satirical magazine that drew the wrath of radical Islam. But, as The New York Times' David Brooks recently opined:

Let's face it: If they had tried to publish their satirical newspaper on any American university campus over the last two decades it wouldn't have lasted 30 seconds. Student and faculty groups would have accused them of hate speech. The administration would have cut financing and shut them down.

The Maroon's editorial—which is one of the most staggeringly unenlightened student op-eds I have ever read (and I've read lots of them!)—gives credence to Brooks' assertion.

The Committee on Free Expression has its work cut out for it, that's for sure.

Hat tip: Robert Shibley / FIRE

Show Comments (79)