The Illogical Basis of That $23 Billion Award Against R.J. Reynolds

On Friday a jury in Escambia County, Florida, decided that R.J. Reynolds should pay $23 billion in punitive damages to Cynthia Robinson, the widow of a smoker who died of lung cancer in 1996. It is not the largest award ever in a case involving a single smoker, but it's close. And like a California jury's 2002 award of $28 billion to a smoker who sued Philip Morris (a sum that the judge later reduced by a factor of 1,000), the case illustrates both the arbitrariness of punitive damages and the implausibility of claiming that tobacco companies managed to conceal the hazards of their products.

Although the main purpose of tort litigation is supposed to be making victims whole, so-called punitive damages explicitly aim to punish wrongdoers. That is usually the function of the criminal justice system, which therefore provides additional protections for defendants, including a higher standard of proof, stricter evidence rules, and penalties prescribed by statute. Attorneys seeking punitive damages do not have to contend with any of those safeguards.

The very concept of punitive damages is oxymoronic, since actual damages (a.k.a. compensatory damages) are a measure of the harm caused by a tort. Punitive damages, by contrast, express a jury's outrage at the defendant's conduct and may be completely unmoored from the injury suffered by the plaintiff (who nevertheless gets the money). In this case, the punitive damages are about 1,400 times the actual damages, which the jury put at $16 million. That huge mutiple seems to violate Florida law, which caps the ratio of punitive to compensatory damages at 3 to 1 (or, in certain circumstances, 4 to 1) unless "the defendant had a specific intent to harm the claimant"—a description that clearly does not apply to a tobacco company with millions of customers, even if it prevented them from making informed decisions by hiding the dangers posed by its products.

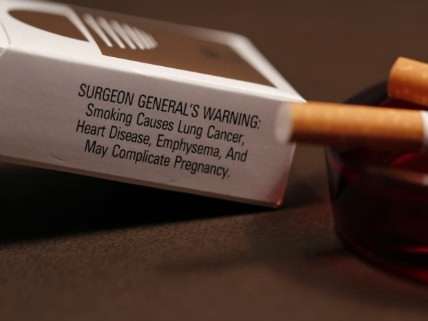

The latter claim, which is central to this sort of lawsuit, is hard to credit. The jury evidently was swayed by evidence indicating that R.J. Reynolds executives questioned the hazards and addictiveness of cigarettes in public while acknowledging them in private. There surely is nothing to admire in that sort of duplicity, but did it actually fool anyone? The first surgeon general's report linking smoking to deadly diseases came out in 1964, and the subject received a great deal of attention during the ensuing decade. By the time Cynthia Robinson's husband began smoking (around the age of 13, according to her testimony, which would have been 1973), every pack of cigarettes carried a warning stating that "The Surgeon General Has Determined That Cigarette Smoking Is Dangerous to Your Health." In 1985 that statement was replaced by rotating warnings referring to specific risks such as lung cancer, heart disease, and ephysema. As for the addictive potential of tobacco, it has been widely acknowledged for centuries, as I show in my book on the anti-smoking movement.

Anyone who began smoking in the 1970s and continued smoking for the next two decades voluntarily assumed the well-known risks associated with the habit. Nothing R.J. Reynolds said or failed to say changes that reality, because it is impossible to conceal common knowledge, no matter how much the tobacco companies might have wished otherwise.

Show Comments (53)