What Keeps Young Europeans Out of Jobs? Stupid Rules.

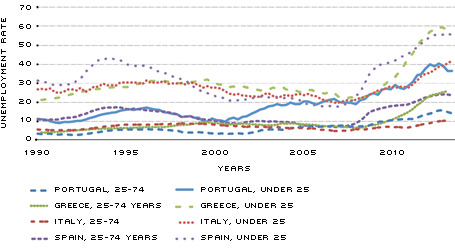

The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis highlights two of its staffers, Economist David Wiczer and Research Associate James Eubanks, for an article they wrote for Regional Economist linking many European countries' sky-high, and continuing, youth unemployment rates to rigid employment rules. Basically, several Mediterranean nations that make it expensive and difficult to hire and fire saw a surge in unemployment for people under 25 during the recession—a surge that really hasn't gone away, and in some cases, is getting worse.

Some high points from the article:

- Italy's youth unemployment rate went from 20 percent in 2008 to 42 percent at the end of 2013.

- Spain's youth unemployment rate went from 21 percent to 55 percent over the same period.

- Greece's youth unemployment rate went from 22 percent to nearly 60 percent during that time.

- Portugal's youth unemployment rate went from about 20 percent to a bit less than 40 percent, and has trended upward since 2000.

By contrast, write Eubank and Wiczer, in the U.S. "the youth unemployment rate rose from 11.5 percent in early 2008 to a high of 19 percent in late 2009 and then began a steady decline. Canada had a similar experience, with a peak of 15.8 percent in late 2009."

What accounts for the huge difference in youth unemployment rates and the continuing joblessness?

The World Bank provides one way to quantify the rigidity of a labor market through its "rigidity of employment index," with higher scores indicating a more rigid market. In 2008, the average for the developed countries in the OECD was 26. Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain were all considerably more rigid, with index values of 43, 38, 47 and 49, respectively.

For context, on the World Bank index, Canada has a value of 4 (the U.S. entry on that chart is blank, but it appears to come in even lower), while Venezuela chalks up a 73. It just may be that countries that make it easier to hire employees when needed and dismiss them when not enjoy—shocker!—healthier employment rates because businesses don't feel like they're assuming huge risk and expense by taking on employees.

Wiczer and Eubanks conclude:

Bad labor markets have repeatedly been shown to have long-lasting effects on youth in many different countries. The postponed plans and stalled careers of millions of young workers are a national concern and should spur reflection on the institutions, policies and labor market structures that contribute to such different experiences across countries.

The World Bank looks in detail at employment regulations here.

Show Comments (64)